Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Testicular cancer is the most common cancer found in men aged 15 to 45 years old. Fortunately, it's considered highly curable, especially when it’s treated at an early stage (Gaddam, 2021).

The key to making sure that you get that early treatment is detection. The easiest way to do this is by performing regular testicular self-exams, similar to what people with breasts should do to check for breast cancer.

So here’s what you need to know about detecting the symptoms of testicular cancer, its causes, and how it's treated.

What is testicular cancer?

Testicular cancer represents about 1% of all tumors in men. It's caused by a complex interaction of environmental factors and genetics (Gaddam, 2021).

This type of cancer has been getting more common. Cases have doubled over the last 40 years, making early detection and treatment even more critical (Gaddam, 2021).

Testicular cancer is ten times more common in males of Northern European ancestry and five times more common in white men of any nationality compared to others. The overall prevalence increases with age (Cedeno, 2021).

What are the signs of testicular cancer?

The most common sign of testicular cancer is a painless lump on your scrotum found by either you or a sex partner. It may also be noticed when you have imaging done for other reasons or are being examined for an injury or other issue in the groin area (Baird, 2018).

Less common testicular cancer symptoms that have been reported include (Baird, 2018):

Acute pain in the testes or scrotum

Dull ache in the scrotum or lower abdomen

Unusual firmness in the testicles

Scrotum feeling heavy

Swollen scrotum

Rarely, men with testicular cancer might have symptoms that indicate that cancer may have spread to other areas of the body, including (Baird, 2018):

Nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea

Enlarged breasts

Headaches

Low back pain

Swollen lymph nodes

Lump in the neck

Respiratory symptoms

Infertility

If you experience any of the above symptoms, you should see your healthcare provider. Several other non-cancerous illnesses can have similar symptoms to testicular cancer, and it will be important to figure out the exact cause of your symptoms (Baird, 2018).

What causes testicular cancer?

Cancer researchers don't know precisely what causes testicular cancer, but they have found some risk factors. These include (Gaddam, 2021; Cedeno, 2021):

Having an undescended testicle (cryptorchidism)

Having a family history of testicular cancer

Having Northern European ancestry

Having chronic infections such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) or Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)

Having Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome)

Being between the ages of 20 and 34 years (51% of all cases occur in this age range)

If you have had cancer in one testicle, you are at higher risk of later developing cancer in the other testicle (Gaddam, 2021).

Exposure to certain types of chemicals and pesticides as a teenager or adult has also been linked to developing testicular cancer. Firefighters, aircraft maintenance personnel, and farmers all have a higher risk of testicular cancer. It is believed that this may be due to chemicals to which people in these professions can be exposed (Cedeno, 2021).

One factor that doesn't likely put you at increased risk for getting testicular cancer? Having a vasectomy (Duan, 2018).

After some studies in the late 80s and early 90s suggested that getting a vasectomy might increase the risk of testicular cancer, researchers set out to find if there was a connection. They analyzed data from over 2,000 men with testicular cancer and found no association between having a vasectomy and the development of testicular cancer (Duan, 2018).

How to check for testicular cancer

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an organization that rates the evidence in support of preventative healthcare measures. For example, they recommend the age when you should start having cholesterol screenings or how often you should get a colonoscopy (Fadich, 2018).

Controversially, the USPSTF doesn't support regular testicular self-exams. This recommendation is because testicular cancer is highly treatable, and false alarms might cause too much anxiety or treatment when it’s not necessary (Fadich, 2018).

While the USPSTF doesn't recommend testicular self-exams, several researchers have petitioned the task force to change this recommendation since it will increase early detection

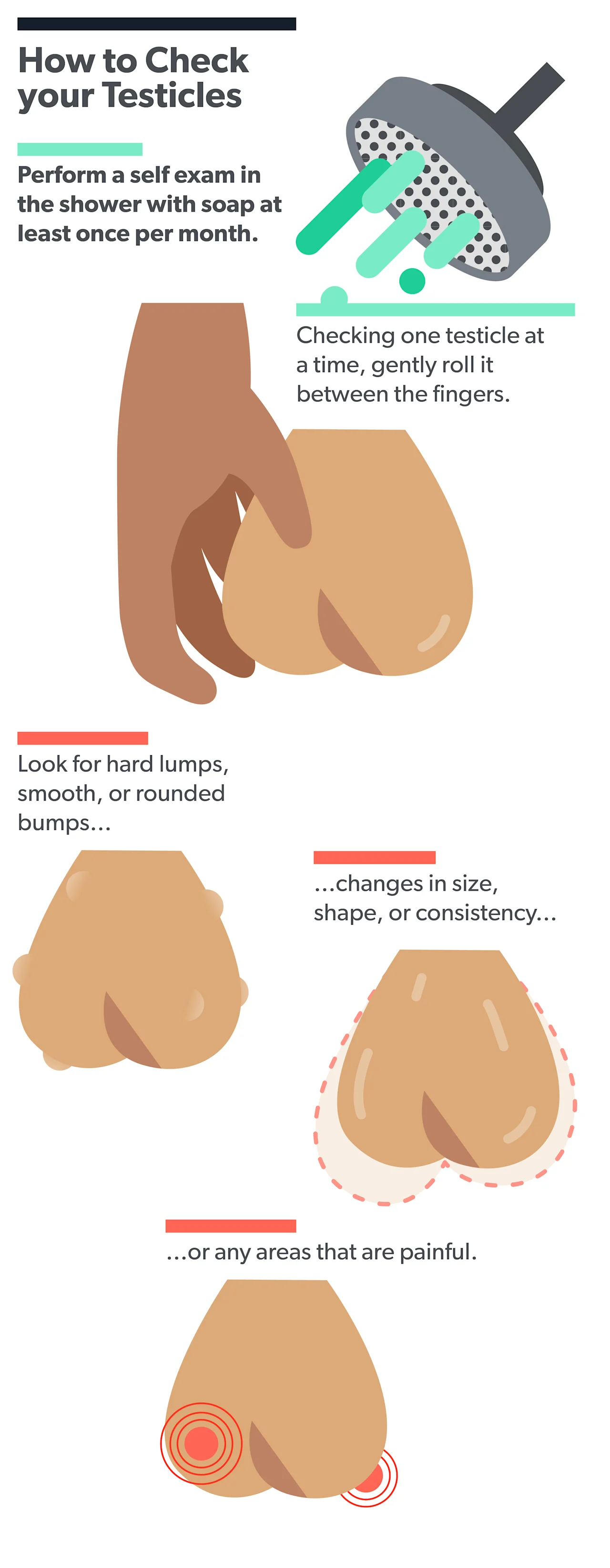

A testicular self-exam is easy and relatively quick to perform:

You might feel a soft, ropy cord leading upward from the top of the back of each testicle. This is called the epididymis and is a normal part of your scrotum. It's also normal to see that one testicle might hang a little lower than the other, or that one is slightly bigger than the other. However, if you see that one is quite bigger than the other, or that there is a recent change in size, then reach out to your healthcare provider.

You might also notice other things about your testicles, such as ingrown hairs, a rash, or other skin problems. These aren't signs of cancer, but you may still want to discuss them with your healthcare provider.When to see a healthcare provider

You should see a healthcare provider if you experience any of the following testicle symptoms (Gaddam, 2021):

Pain

Swelling

Lumps, masses, or changes in testicle size

Rash

Not all of these symptoms necessarily indicate cancer, but they usually mean something is going on that might need immediate attention. For example, pain isn't usually a sign of testicular cancer, but it can be a sign of infection or testicular torsion. Testicular torsion is an emergency situation where the blood flow to your testicle is blocked, and it usually needs to be fixed within a few hours to save the testicle (Velasquez, 2021).

Your provider will ask you questions about your general health and the symptoms you're having. They will then perform a physical exam and an ultrasound of your testicle to help make a diagnosis. If needed, further workup could include blood tests, a biopsy, tests for tumor markers, or a CT scan (Gaddam, 2021; Cedeno, 2021).

What is the treatment for testicular cancer?

For all stages of testicular cancer treatment, the first step is an orchiectomy (removal of the affected testicle). After that, other recommended treatment options depend on the type and stage of cancer you have. This can include (Chung, 2016):

Radiation therapy

Chemotherapy

Lymph node removal

Active surveillance

When combined with orchiectomy, each of these options can play a role in curing testicular cancer. If the first treatment chosen isn’t successful, it's very likely that another type of treatment will be. The testicular cancer survival rate is very high (Chung, 2016).

Your provider will discuss all of the advantages and disadvantages of each option with you. You will have a treatment team with several different healthcare specialists, such as an oncologist and a urologist, working together for your cancer care and follow up. They will help you achieve the best outcome possible, minimize side effects, and maintain your quality of life (Koši Kunac, 2020).

What’s the prognosis for testicular cancer?

Hearing the word “cancer” is scary, no matter what. The good news is testicular cancer is one of the most curable types of cancer. Up to 90% of cases can be cured and over 95% of men diagnosed with testicular cancer are still alive five years later (Gaddam, 2021).

Many factors go into determining the likely outcome when you’ve been diagnosed with cancer. These include (Gaddam, 2021):

The type of cancer

The size of the tumor

How far the cancer cells have spread into other parts of the body

In general, the sooner you find out that you have cancer and start treatment, the more likely you are to have favorable results. Even men who already have widespread cancer when it's found can potentially be cured with treatment, though it’s important not to delay care if you are experiencing symptoms (Gaddam, 2021).

If you have concerns about testicular cancer, speak with your healthcare provider.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Baird, D. C., Meyers, G. J., & Hu, J. S. (2018). Testicular cancer: diagnosis and treatment. American Family Physician, 97 (4), 261–268. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29671528/

Cedeno, J. D., Light, D. E., & Leslie, S. W. (2021). Testicular seminoma. [Updated Aug 12, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Sep. 26, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448137

Chung, P. & Warde, P. (2016). Testicular cancer: germ cell tumours. BMJ Clinical Evidence, 2016,

Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4704678/

Duan, H., Deng, T., Chen, Y., Zhao, Z., Wen, Y., Chen, Y., et al. (2018). Association between vasectomy and risk of testicular cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 13 (3), e0194606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194606. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5864054/

Fadich, A., Giorgianni, S. J., Rovito, M. J., Pecchia, G. A., Bonhomme, J. J., Adams, et al. (2018). USPSTF testicular examination nomination-self-examinations and examinations in a clinical setting. American Journal of Men's Health, 12 (5), 1510–1516. doi: 10.1177/1557988318768597. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6142159/

Gaddam, S. J. & Chesnut, G. T. (2021). Testicle cancer. [Updated Jul 25, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Sep. 26, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563159/

Koši Kunac, A., Gnjidić, M., Antunac Golubić, Z., & Gamulin, M. (2020). Treatment of germ cell testicular cancer. Acta Clinica Croatica, 59 (3), 496–504. doi: 10.20471/acc.2020.59.03.14. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8212650/

Velasquez, J., Boniface, M. P., & Mohseni, M. (2021). Acute scrotum pain. [Updated Jul 18, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Sep. 26, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470335/