Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

When I went on birth control when I was 18 years old, I remember heaving a sigh of relief. “Thank God I don’t have to worry as much about getting pregnant anymore,” I thought to myself. Popping my daily pill, which I fondly referred to as my “Altoid,” helped me feel less anxious.

Fast-forward nearly 15 years later. Now that I’m in my late twenties and considering when I want to have kids, things are a little different. Instead of my birth control relieving anxiety, I find it’s actually causing it. Did the years of diligently taking my “Altoid” actually harm my ability to one day conceive? (The quick answer: no.) Is my current contraception method, the Mirena intrauterine device (IUD), negatively impacting my fertility, due to hormones or the fact that there’s a plastic foreign object, you know, just chilling out in my uterus? (Again, no.) When I take it out in a few years, how long will it be until my fertility returns? (Right away.)

Online articles with frightening headlines left me confused and anxious. So, discouraged yet determined, I turned to science. I spent hours scouring clinical studies and trustworthy sources for conclusions. As a result of my late night research project, I learned a lot about what experts have to say about birth control and how it influences fertility.

Consider this your scientific guide–sans scientific jargon — to being able to better answer the question: Based on what the medical community knows, how do different types of birth control offered in the US affect fertility?

Part I: Non-Hormonal Birth Control

Sterilization

Often referred to as a woman “getting her tubes tied,” sterilization is a one-time procedure that hinders pregnancy. However, unlike other contraceptive methods discussed in this guide, sterilization is a permanent, irreversible form of birth control.

There are two common types of sterilization: tubal ligation and tubal implantation. During the former, a woman’s fallopian tubes are cut, sealed, or clipped, which immediately prevents pregnancy. For the latter, a tubal implant (a small, spring-like coil) is inserted into each fallopian tube. After about three months, scar tissue will form and fully block the tubes, which prohibits conception.

Post-sterilization, a woman is most likely no longer able to conceive. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, out of 100 women who have a sterilization procedure each year, less than one may become pregnant.

Fertility awareness methods

Fertility awareness methods are natural forms of birth control like tracking your cycle, taking your temperature, and observing your cervical mucus, all to predict when you ovulate. Pregnancy is avoided by not having sex on fertile “wet” days (those near ovulation).

Because fertility awareness methods are natural and do not incorporate medical variables or interventions, like extra hormones or a foreign object, they don’t pose a risk to fertility.

Copper IUD

The copper IUD (primarily known as the Paragard), is a T-shaped, FDA-approved device made from plastic and copper that’s inserted in the uterus. The copper ions released from the Paragard are toxic to sperm, which prohibits them from fertilizing an egg.

In a 2015 study, researchers at top medical schools recruited 69 former IUD users (50 of the 69 used a copper IUD) and 42 former non-IUD users. All of the women were sexually active, aged 18 to 35, and discontinued birth control because they desired pregnancy. Here's what they found:

At 12 months, pregnancy rates were similar between the two groups: 81% of IUD users became pregnant compared to 70% of non-IUD users.

There was also no significant difference in the amount of time it took for women in the two groups to become pregnant.

Part II: Hormonal Birth Control

Hormonal IUD

Two of the most popular types of hormonal IUDs are the Mirena and Skyla, which release levonorgestrel (another word for the well-known hormone progesterone) to prevent pregnancy. Progesterone thickens the mucus around your cervix, making it difficult for sperm to swim up to and fertilize an egg. It also thins the uterine lining, which makes it more difficult for a fertilized egg to implant.

A few studies have explored fertility post-hormonal IUD:

The same 2015 study from the last section revealing that former IUD users and non-IUD users had similar pregnancy rates is encouraging for Mirena and Skyla users, too. However, only 17 of the women used a levonorgestrel-based IUD (compared to the 50 who used copper).

But a 2011 report, focused on reviewing the available literature on hormonal IUDs, states, “After removal of the intrauterine system (IUS), normal fertility is regained after a few months, with a near-normal 80% of women able to conceive within 12 months.”

The International Journal of Women’s Health came to a similar conclusion in 2009: “The contraceptive actions of the levonorgestrel IUD reverse soon after removal of the device,” write the authors. “One-year pregnancy rates after removal are 89 per 100 for women less than 30 years of age — rates are similar to women who had not been using any form of birth control.” It’s important to keep in mind, though, that these statistics are based on studies from 1986 and 1992.

Oral contraceptives

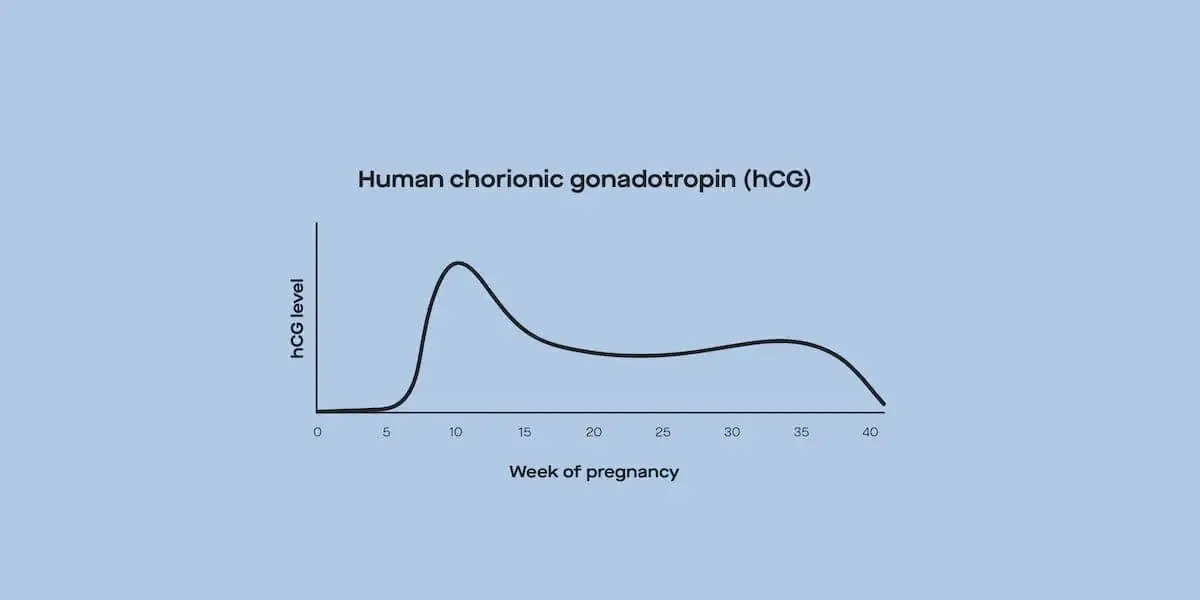

Primarily known as birth control pills (or in my case, Altoids), oral contraceptives rely on progesterone and estrogen (some contain both, while others only contain progesterone) to prevent pregnancy.

Researchers at Boston University’s School of Public Health discovered in 2013 that long-term users of oral contraceptives, similar to short-term users, experienced a temporary delay in fertility when compared to those discontinuing barrier contraceptives (like condoms or diaphragms). “But after that, monthly fertility rates are comparable to those of women stopping other methods of contraception,” says co-author Elizabeth Hatch.

In 2009, researchers tracked nearly 60,000 oral contraceptive users to determine their chances of conceiving after discontinuation. About 20% achieved a pregnancy in their first cycle after cessation and 80% within the first year after discontinuation, irrespective of the type of oral contraceptive used.

Vaginal ring

This form of birth control is marketed as the NuvaRing. It’s a flexible, transparent ring that’s inserted into the vagina. The NuvaRing contains four weeks’ worth of progesterone and estrogen. Once inserted, it remains in the vagina for three weeks and is then discarded. After a ring-free week (when menstruation occurs), a woman will insert a brand new ring.

Compared to all other contraceptive methods, it was most difficult to find a recent report on the NuvaRing’s influence on fertility. But this study points to women’s ability to immediately ovulate — not necessarily get pregnant — after abandoning the NuvaRing. The authors write, “Subsequent follow-up in the next untreated cycle revealed that ovulation occurred in 27 of 29 women, highlighting the rapid return to fertility after discontinuation of this method.”

Implant

The Nexplanon, Norplant, and Implanon are three common brand names for contraceptive implants. A small rod (about the size of a matchstick) is implanted below the skin in a woman’s upper arm and then releases progesterone.

Researchers in India observed the return of fertility for 74 former Implanon users. After the implant was removed, 50 of the women accepted alternative methods of contraception. But of the remaining 24, 40 percent had ovulation return within one month. 29.16 percent conceived within 3 months, 62.50 percent conceived within 6 months, 66.66 percent conceived within 9 months, and 95.8 percent conceived within 12 months.

Shot or Injection

This FDA-approved birth control option is known in the US as the Depo-Provera. Women who choose this method are given a shot of progesterone every three months.

This is the only hormonal birth control that researchers know can cause a delay in conception compared to other birth control methods. Most clinical studies discussing the Depo-Provera’s impact on fertility cite two early studies from 1984 and 1998. The 1984 study noted that women who stopped getting Depo-Provera shots experienced a 5.5 month median delay of conception, compared to 3 months for oral contraceptive users and 4.5 months for IUD users.

But the 1998 study is the source of the fertility information that’s widely cited today by websites like Planned Parenthood and the Mayo Clinic. The study reads, “Although fertility resumes on the average 10 months following the last injection, suppression of ovulation occasionally persists for as long as 22 months. Consequently, Depo-Provera is not an appropriate choice for women who may wish to conceive within the next two years.”

A lack of research available

For me, parsing through clinical studies makes me feel more at peace (and like I wish I had paid more attention in statistics). However, I also wish there were more studies with larger sample sizes on the effect of the Mirena on fertility, which is my current method of contraception.

To be honest, I learned a lot about what information is not available. There’s a lack of research on women’s health in general. Many studies rely on statistics from studies conducted in the 1980s and 1990s (when my 60-year-old mom was on birth control). Plus, I had trouble finding “true” control groups in these contraception studies. Variables, such as the type of IUD used, socioeconomic status, age, frequency of intercourse, and the number of years a woman has been using a contraceptive method, make it difficult to conduct a truly flawless experiment.

Though PubMed may not have all the answers, pursuing hormone testing to understand my fertility is one sure-fire way to get the real, hard data I crave. Plus, it’s about my body — my uterus may behave totally differently than the 100 women’s observed in an experiment. But whether you choose to pay for your own personal fertility dashboard or simply read a scientific study, seeking the information that’s available to you (that’s not anecdotal or a scare tactic) is always better than remaining in the dark.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.