Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women in the United States, according to the CDC, and 5-10% of breast cancers are hereditary.

In this article we explain what the implications are of having a mutation associated with hereditary breast cancer and how you should think about fertility preservation.

Here are the main points summarized:

Mutations in BRCA-1 and 2 are the most common cause of hereditary breast cancer. Having these mutations can mean developing breast cancer at a younger age and in both breasts, as well as an increased risk of ovarian and other cancers.

Based on your family history, you may want to see a genetic counselor to learn if getting tested for these genes is right for you.

If you test positive for BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 genetic mutations, there are options for managing your increased risk of cancer, but these can impact your fertility.

Talk to your doctor about options for fertility preservation, which include egg or embryo freezing.

If or when you are ready to get pregnant, you’ll also have to decide whether or not you want to do genetic testing (including things like genetic testing on embryos or amniocentesis) to prevent passing on the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation to your future children.

Making decisions about your health and future fertility can be intense and overwhelming. Don't hesitate to seek support.

What is hereditary breast cancer?

Our parents can pass along mutations in DNA that increase the risk of breast cancer. The most common cause of hereditary breast cancer is passed along through mutations in the BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes. If you inherit a mutation, sometimes called a pathogenic variant, from a parent (your mother or your father), you have a higher risk of getting breast cancer — a 7 in 10 chance by the age of 80, according to BreastCancer.org. That risk is increased if you have a number of family members who have had breast cancer.

Those with mutations in BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 are also more likely to develop breast cancer at an earlier age (the median age for diagnosis in the US is 62) and more likely to have cancer in both breasts. And the increased risk of cancer is not limited to breast cancer—there’s also an increased risk of developing melanoma, colon, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers.

Testing for BRCA-1 or BTCA-2 genetic mutations

A blood (or in some cases, a saliva) test can tell you if you're a carrier for a mutation in the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 genes. Check out the Mayo Clinic for a full list of recommendations as to who should get tested. Here are a few of the criteria:

A relative with a known BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutationA family history of breast cancer diagnosed before age 45

A family history of breast cancer and Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish ancestry (an estimated 1 in 40 Ashkenazi Jewish women have a BRCA gene variant)

A history of breast cancer at a young age in two or more blood relatives, such as your parents, siblings or children

A mother with ovarian cancer

To get tested, you usually first meet with a genetic counselor. That can be arranged through your primary care doctor, your OB-GYN, or your fertility doctor (if you’re already seeing one). Currently, most genetic testing companies offer a cancer gene panel, which tests more than just the BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 genes (since there are mutations in other genes that result in an increased risk of breast cancer).

Meeting with a genetic counselor will help you understand the test and think about the next steps. You should bring information about your family medical history and your own health history, as well as any questions you have — and, if you want, bring a person you trust to support you. You may decide not to take the test after meeting with the genetic counselor, but if you do choose to move forward, here's what you should know about the results:

You can test positive, negative, or uncertain for mutations in BRCA-1 or BRCA-2.

A negative result means that a BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 mutation wasn't found. A negative result doesn't mean you won't get cancer, but rather that your risk of cancer is in line with that of the general population.

An uncertain result (called VUS, or Variant of Unknown Significance) occurs when a mutation is found that may or may not be associated with an increased risk of cancer. With future research, an uncertain result may be reclassified into a positive or negative result, so you should meet with your genetic counselor to talk about how to proceed.

If you test positive for a BRCA mutation, it doesn't mean you're absolutely going to get cancer. However, it does mean you have a significantly higher risk than someone who doesn't have the mutation.

Before making any medical decision about how you're going to deal with a positive result, you should consult your doctor and a genetic counselor.

The implications of a positive BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 result

Those who test positive for a BRCA mutation are at an increased risk of developing both breast and ovarian cancer. There are a number of procedures and medications you can take to reduce your cancer risk, and some of these can impact your fertility.

Managing the risks of carrying a BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 genetic mutation

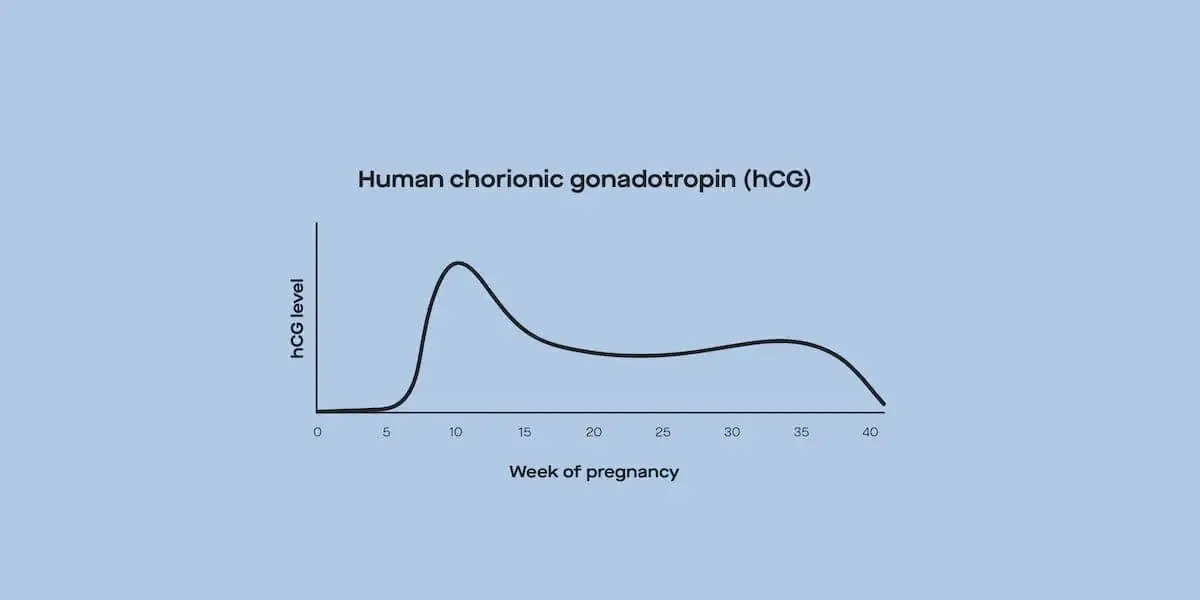

BRCA-1 mutations can carry up to a 50-85% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer in both breasts at a young age, as well as a 40-60% chance of developing ovarian cancer. BRCA-2 mutations have a lesser risk of ovarian cancer, and often result in cancer at an older age. (Note: Ovarian cancer often begins in the fallopian tubes, and can present as early as age 35 for someone with a BRCA-1 mutation.)

So, how might a person who tests positive for any one of these mutations manage her risk? Patients with a certain BRCA-1 mutations may be presented with the option for prophylactic (preventive) bilateral mastectomy (the removal of both breasts) and/or risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (the removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes). According to Mayo Clinic, for people with the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation, prophylactic mastectomy reduces the risk of developing breast cancer by 90-95%.

But there are many other factors to take into consideration when you're thinking about getting surgery, including your age and medical history. The decision is highly individual and should follow a long consultation with a gynecologist oncologist and genetic counselor.

Options other than surgery include enhanced frequency of screening in order to detect breast cancer at an early stage, which could include exams every 6 months (unfortunately, monitoring for ovarian cancer is much harder).

BRCA genetic mutations & family planning

If you have a BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 genetic mutation, then you have a 50% chance of passing the mutation on to your child — whether you’re a man or woman.

If you have a BRCA mutation and want children one day, you’ll potentially be facing some fertility and family planning decisions, including:

Getting pregnant naturally

Freezing your eggs, storing them, and eventually doing IVF when you want to have children

Going through the IVF process when you’re ready to have childrenUsing donor eggs (or donor sperm, if you have a male partner who has the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation) and going through the IVF process

Adoption

If you have a BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation, the path to having a child can be difficult and emotional, so it’s best to talk through all your options with a genetic counselor.

BRCA genetic mutations & fertility preservation

If you are considering having your ovaries removed per a doctor’s recommendation, you may want to consider freezing your eggs, or, if you have a partner, freezing embryos.

Egg and embryo freezing success rates depend on a number of factors, including how old you are. For example, if you're in your mid 30s when you learn that you're positive for a BRCA-1 mutation, your ovarian reserve (how many eggs you have left) may already be declining due to age.

Some carriers of BRCA mutations present with a lower ovarian potential than expected for their age group. According to Dr. Julie Lamb, MD, FACOG, a board certified reproductive endocrinologist, infertility specialist at Pacific NW Fertility, and member of Modern Fertility’s Medical Advisory Board, “There is some evidence that women who carry a BRCA gene mutation have lower ovarian reserve and potentially shorter reproductive windows.”

"Women should get tested and talk to a board certified reproductive endocrinologist to better understand if fertility preservation if right for them,” Dr. Lamb explains.

Genetic testing for BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutations while trying to conceive

If or when you are ready to get pregnant, you’ll also have to decide whether or not you want to do genetic testing to prevent passing on the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation to your future children.

Dr. Sharon Briggs, Modern Fertility’s head of Clinical Product Development, has a PhD in genetics. She says, “For women who have a BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation, there’s a 50% chance that each embryo will test positive for the same BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 mutation.”

If you get pregnant naturally: Your doctor may recommend an amniocentesis, which tests the cells around the fetus and can help determine whether the BRCA mutation was or was not passed on.

If you choose to do IVF: “After retrieving eggs and fertilizing them with sperm, embryos can be screened for the same specific mutation that the patient carries. This kind of preimplantation genetic testing is referred to as PGT-M,” Dr. Briggs explains. “Couples can then decide to only transfer the embryos that test negative.” It's important to keep in mind that you might not have any embryos that test negative for the BRCA mutation. In this case, you may decide to:

Do another cycle of egg retrieval and genetic testing.

Implant an embryo with a BRCA mutation.

Or, consider other family building options like egg donation or adoption.

While embryo genetic testing has a relatively high accuracy rate, your doctor might still recommend that you have an amniocentesis once you’re pregnant.

Real women, real decisions

So far, we've been talking in hypotheticals, but discovering your family carries a history of hereditary breast cancer has a real impact on women and their fertility decisions.

"I definitely knew my family's history of BRCA-2 mutations potentially narrowed my timeline without knowing anything else about my fertility," says Grace Ann, who's 31 years old. Her mother and sister have both tested positive for a BRCA-2 gene variant, which motivated her to check out her own status.

"I wanted to test and know if I was positive because if I was in fact a BRCA2 carrier, I'd elect to have the preventive surgeries (a double mastectomy/reconstruction, and removing my tubes and ovaries) to lower my risk to the normal populations as my mom did. The current recommendation for BRCA-2 is to do this when you're done having children or by menopause age since the onset risk is statistically later in life. My first thought after my mom shared that she was positive, I thought was "How short will my fertility window be if I'm positive?"

Grace Ann ultimately tested negative for BRCA-2, which proved to be an enormous relief.

"It allows me to not feel rushed with having kids - if I was positive, then I'd want to have all of my kids pretty quickly to make sure I could have the preventive surgeries in the recommended time frame."

Miriam, who just turned 30, has a significant family history of breast cancer. Her mother and both of her maternal aunts were diagnosed before the age of 50."I haven't been tested for the gene," Miriam says. She’s been proactive, though — going into her doctor a couple times a year since she was 25 years old for annual check-ups.

When it comes to her fertility, she knows there's a bilateral mastectomy and a salpingo-oophorectomy in her future.

"I honestly never have been interested in giving birth in the first place," she says, "and so the potential surgery isn't really impacting my timeline. If I were planning on giving birth to children, I'd be much more motivated to get the genetic test done."

Ultimately, she and her partner have decided they will likely adopt children.

Support for people who test positive for BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 mutations

Undergoing genetic testing, getting the results, and making decisions about them is no joke, and you shouldn't have to go through it alone.

A genetic counselor will help you process what your results mean, and your doctor can help you decide what you might do next. Additional support can be found in peers who have gone that road before you. Here are two good options:

Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE) connects women with hereditary cancer risk, as well as those who have been diagnosed, with confidential support.Sharsheret is an organization of and for Jewish women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and who are at risk. Their Peer Support Network connects newly diagnosed and high risk women to share their experiences with one another.

It’s important to remember: you are not alone, and you deserve support. Moreover: the discovery of a BRCA mutation will help you take control over your life and help prevent getting cancer!

This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Sharon Briggs (Modern Fertility’s head of Clinical Product Development) and a member of the Modern Fertility Medical Advisory Board.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.