Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Endometriosis is a common condition in women’s health, but there are still many unanswered questions.

Researchers think that endometriosis affects about 10–15% of women of reproductive age, but they really aren’t sure. Not everyone has symptoms and those that do sometimes get the wrong diagnosis (Tsamantioti, 2021).

Here’s what we do and don’t know about endometriosis, including its symptoms and how to treat it.

What is endometriosis?

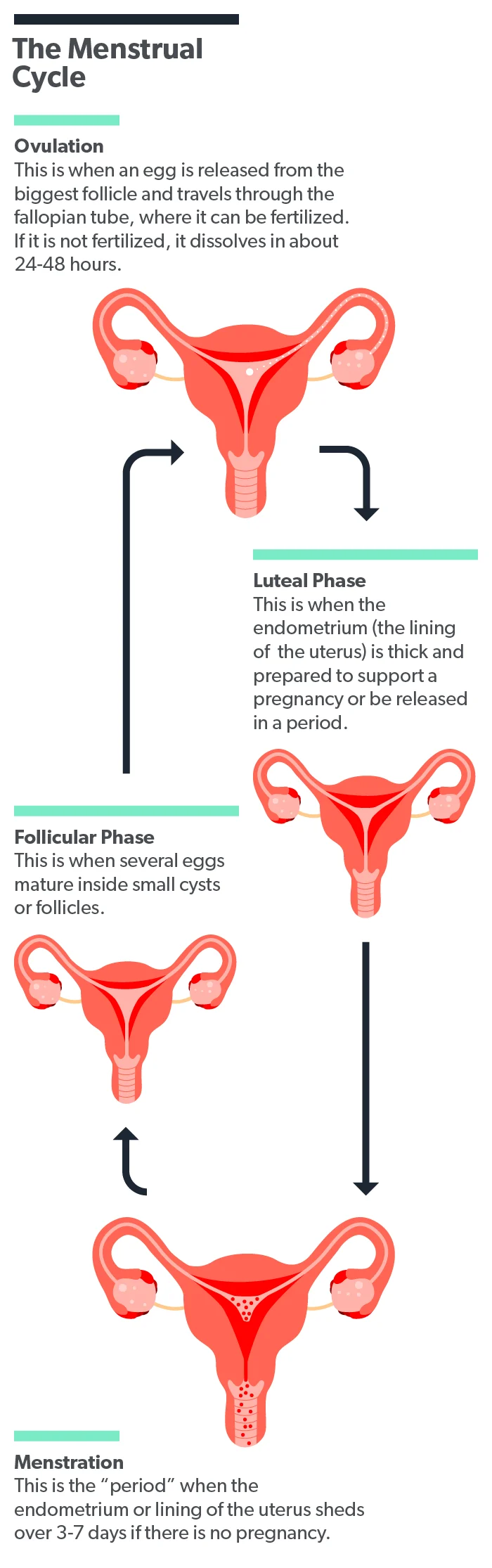

The endometrium is the inner lining of the uterus. It grows thicker every month in response to hormones so that it can receive a fertilized egg and support a pregnancy. If no pregnancy happens that month, the body sheds the endometrium. This is your monthly menstrual cycle.

Endometrial tissue should ideally only be inside the uterus, but with endometriosis, that tissue also grows outside the uterine cavity. Endometriosis lesions can appear in multiple places throughout the body. The most common locations are the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Other body locations where it can occur include (Tsamantioti, 2021):

The intestines

The bladder

The ureters (the tubes that bring urine from the kidneys to the bladder)

The urethra

The lining of the heart or lungs

The central nervous system (brain and spinal cord)

The endometrial tissue outside of the uterus still responds to your body’s hormones the same way that the endometrium in the uterus does. That means it grows each month and then breaks down during your menstrual cycle. Unlike the lining of your uterus, though, the tissues outside the uterus have no way to exit the body. This trapped tissue can cause pain and other medical problems (Dydyk, 2021).

What are the signs and symptoms of endometriosis?

The signs of endometriosis and their severity can vary from person to person. Unlike many other illnesses, the amount of symptoms you have doesn’t always directly relate to the size or number of endometriotic tissue you have (Tsamantioti, 2021).

Clinicians are much more likely to diagnose endometriosis in females presenting with more common symptoms, such as (Tsamantioti, 2021):

Pelvic pain

Heavy, painful periods

Bowel and bladder problems

Infertility

Unfortunately, it can often take 4–11 years to get a proper diagnosis after symptoms start. This delay is likely because there currently isn’t a specific lab test to detect the disease, and this condition can cause a wide range of symptoms that can look like other conditions (Tsamantioti, 2021)

Between 50% and 70% of women with chronic pelvic pain will be diagnosed with endometriosis. The severe pain associated with endometriosis is usually described as chronic and as getting worse over time. The pain is also cyclic (meaning it comes and goes) due to the tissues growing and shedding in the pelvic cavity with the body’s monthly hormonal changes (Tsamantioti, 2021; Dydyk, 2021).

Endometriosis has also been linked with infertility or trouble getting pregnant. Researchers aren’t exactly sure of the reason for the connection, but 30–50% of women with endometriosis will have at least some trouble getting pregnant (Macer, 2012).

One theory about endometriosis infertility is that the body’s attempts to clear away the endometrial tissue outside the uterus lead to inflammation. This inflammation leads to pain, scarring of the tissues, and the forming of bands of scar tissue that can cause pelvic organs to stick together (adhesions). This inflammation and scar tissue can lead to trouble conceiving (Bulun, 2019).

What causes endometriosis?

Medical researchers don’t know the exact cause of endometriosis, but there are many theories. However, none of these theories can explain all the symptoms that people with endometriosis experience (Tsamantioti, 2021).

The most widely believed theory is that blood and fluid from your menstrual period can sometimes flow backward up the fallopian tubes and into the pelvic area. This is called retrograde menstruation. The cells in this fluid can then implant and grow outside of the uterus, causing endometriosis (Tsamantioti, 2021).

Another theory, called the coelomic metaplasia theory, suggests that the cells lining the inside of the abdomen (called the peritoneum) and organs can transform into endometrial cells. This happens when they are exposed to abnormal levels of hormones and growth factors. This theory could explain why women without a uterus can still have endometriosis, such as those who’ve had a hysterectomy. It also might explain the extremely rare cases of men with endometriosis (Tsamantioti, 2021).

Risk factors for endometriosis

Several factors have been associated with an increased risk of developing endometriosis. These support the theory that endometriosis is linked with hormone status (high estrogen and low progesterone) in women. These risk factors include (Tsamantioti, 2021):

Starting your period before age 11

Getting your period more often (your cycle is shorter than 27 days)

Heavy menstrual bleeding

No history of pregnancy

Several factors predict a lower risk of having endometriosis. Researchers think this is because they cause lower estrogen levels in the body (Tsamantioti, 2021).

Pregnancy

Extended breastfeeding

Using oral contraceptives (birth control pills)

Having a tubal ligation

Smoking

The fact that smoking is associated with a lower risk of endometriosis is controversial because it is highly damaging to every other aspect of your health. Exactly why smokers have a lower risk of endometriosis isn't clear, but it may have to do with the fact that female smokers typically have lower estrogen levels (Tsamantioti, 2021). Still, the risks of smoking far outweigh this potential benefit.

How do you get diagnosed with endometriosis?

You’ll need to see a healthcare provider to be diagnosed with endometriosis. They will start by asking detailed questions about your health history and performing a pelvic exam. Your healthcare provider will want to know if you have any history of (Tsamantioti, 2021):

Family members with endometriosis

Pelvic pain

Ovarian cysts

Pelvic surgeries

Infertility

The findings of your physical exam will depend on the location and size of the endometriosis tissue. Some women have tenderness and masses of tissue that can be felt, while others don’t. Even if your provider doesn’t find anything with a physical exam, you can still have endometriosis (Tsamantioti, 2021).

The best way to diagnose endometriosis for sure is to have surgery to look inside your abdomen (called a laparoscopy) and let the surgeon take tissue biopsy samples. This is an invasive procedure and might be more than you need if your symptoms are only mild. So, healthcare providers usually rely on less intrusive means (Tsamantioti, 2021).

Other methods of diagnosing endometriosis that don't involve surgery include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound. Ultrasound, in particular, is very effective at helping providers find endometriosis tissues around the ovaries and in the pelvis (Tsamantioti, 2021).

Is there any endometriosis treatment?

There is no cure for endometriosis, but several types of effective treatment help manage the symptoms. The therapy goals for endometriosis are controlling pain, improving quality of life, preserving fertility, and reducing the need for surgery (Bulun, 2019).

Medications

First-line medications to treat endometriosis include over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen for pain and hormonal contraceptives (birth control) to reduce ovulation and estrogen levels (Tsamantioti, 2021).

If these medications don’t work well enough for you, your provider might consider a class of drugs called gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists. GnRH agonists cause a reduction in a few different hormones in the body and slow the growth of endometriosis tissues (Brown, 2014).

An intrauterine device (IUD) containing levonorgestrel has also been shown to be more effective than a placebo to reduce endometriosis symptoms (Brown, 2014).

Surgery

Endometriosis surgery, in which endometriosis tissue is removed, is another treatment option available. Due to the risks and complications with any surgery, it is usually only considered when medications haven’t worked. The major advantage of surgery is that removing endometriosis and scar tissue can simultaneously relieve pain and enhance fertility (Tsamantioti, 2021).

In women with endometriosis undergoing fertility treatments, surgery to remove endometriosis tissue improved unassisted pregnancy rates in the 9–12 months following surgery (Brown, 2014).

Assisted reproduction

Women with endometriosis experience lower fertility rates than those without; however, many women with mild to moderate endometriosis can still get pregnant without any interventions. Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) can help those with more severe endometriosis (Macer, 2012).

Researchers don’t know how much endometriosis affects the success of in-vitro fertilization (IVF), but IVF appears to be the most successful option for women with all stages of endometriosis. Some reproductive medicine specialists may also recommend using medications or surgery before undergoing IVF to improve the chances of getting pregnant (Macer, 2012; Brown, 2014)

When to see a healthcare provider

You should make an appointment with a healthcare provider if you have any signs or symptoms that you think might be endometriosis.

Researchers have found that many women experience pain symptoms for over two years before seeking medical care (Dydyk, 2021). While we can’t cure endometriosis, several effective treatments can help you improve your comfort and quality of life, so it’s best to get help as soon as you can.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Brown, J., & Farquhar, C. (2014). Endometriosis: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. The Cochrane Database Of Systematic Reviews, 2014 (3), CD009590. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009590.pub2. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6984415/

Bulun, S. E., Yilmaz, B. D., Sison, C., Miyazaki, K., Bernardi, L., Liu, S., et al. (2019). Endometriosis. Endocrine Reviews, 40 (4), 1048–1079. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00242. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6693056/

Dydyk AM, Gupta N. (2021). Chronic pelvic pain. [Updated 2021 Jul 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554585/

Macer, M. L., & Taylor, H. S. (2012). Endometriosis and infertility: a review of the pathogenesis and treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics Of North America, 39 (4), 535–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2012.10.002. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3538128/

Tsamantioti ES, Mahdy H. (2021). Endometriosis. [Updated 2021 Feb 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567777/