Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

The best time to get pregnant is a personal choice for everyone, which can be affected by the search for a partner or career choices. Many people learn that when they decide they want to start trying for kids, it can be more difficult to get pregnant as you get older.But age aside, many other factors can affect a person’s chance of getting pregnant, including health conditions like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, fibroids, thyroid conditions, and more. And it’s not only female factors that factor in here—sperm quality is important, too.

Still, if you want to see a female fertility age chart, we’ve got you covered. But first, a little context.

What is the best age to get pregnant?

Those with ovaries are born with all the eggs they’ll ever have, about one million. Unlike sperm, eggs do not replenish themselves and begin to deplete before you’re even born. By the time a girl hits puberty, only about 300,000 eggs remain. The number of eggs you have then decreases with every menstrual cycle, with multiple eggs lost each month until a person reaches menopause (around age 50) and no more eggs are released (Faddy, 1995).

Although just one egg is typically available for fertilization during each menstrual cycle, hundreds to more than 1,000 immature oocytes (eggs) are lost each month (Faddy, 1995). That’s why age is a pretty important factor in female fertility.

According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, female fertility peaks in the late-20s to early-30s (ASRM, 2021).

Chances of getting pregnant by age chart

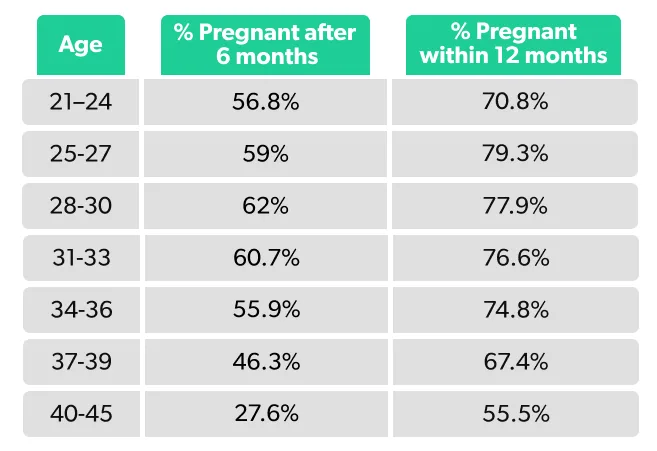

Here’s a breakdown of a woman’s statistical probability of getting pregnant within six or 12 months of trying, depending on her age (Wesselink, 2017):

As you can see, most women have the greatest chance of getting pregnant in their 20s to 30s, with a steeper decline in fertility after 35. With that said, plenty of women get pregnant after 35.

About 80% of people will conceive within the first six months of trying. If you’re over 35, guidelines recommend seeing a fertility specialist for testing if you don’t get pregnant within six months of trying. Those under 35 should try for a year before seeking help from a fertility clinic (unless they have known issues) (ASRM, 2021).

Fertility in your 20s

Your chance of pregnancy is the highest in your 20s. A study of nearly 3,000 American and Canadian couples trying to conceive found that those between the ages of 25–27 had the highest pregnancy rate, with 79% conceiving within a year of trying compared to 55% of 40–45-year-olds (Wesselink, 2017). Those in their 20s also have a lower risk of miscarriage. One study suggested that those between the ages of 26–30 have the lowest rate of major chromosomal abnormalities (Franasiak, 2014).

Fertility after 30

Research shows fertility stays relatively stable between the ages of 28–33 (Wesselink, 2017). As you make your way through your 30s, fertility starts to decline, but it’s not an immediately steep drop-off. The fertility rate of women 34–35 years of age is about 14% less than that of someone 30–31 (George, 2010).

Your risk of miscarriage is also low in your early-30s. The miscarriage rate for those under 35 is between 9–12% in the first trimester (ASRM, 2012).

Around the age of 38, the rate at which you lose eggs doubles, leading to a more rapid decline in fertility (Faddy, 1995). This increased egg loss can make it more difficult to get pregnant—not just because there are fewer eggs, but because these eggs tend to have more genetic or chromosomal abnormalities. These genetic abnormalities within the egg can decrease the odds of conception and increase the risk of miscarriage (ASRM, 2012).

While your chances of conceiving are greater before your late-30s, people can and do get pregnant in their late-30s. A study of Danish women found that 72% of women between 35 and 40 got pregnant within 12 months of trying, compared to 87% of women between the 30 and 34 (Rothman, 2013).

Fertility in your 40s

By the time you reach 40, your fertility is about half of what it was in your late-20s and early-30s (ASRM, 2021). Research looking at cultures that reproduce until menopause shows that the average age of last birth occurs around ages 40–41 (Eijkemans, 2014).

People can get pregnant in their early-40s, but the odds of a live birth, even after an embryo implants, are much lower than for younger women. With age comes reduced egg quality, which leads to a higher risk of pregnancy loss, often due to an irregular number of chromosomes within the egg. Because of this, the miscarriage rate for those over 40 is close to 50% (ASRM, 2012).

Unfortunately, age also decreases the likelihood of success for fertility treatments. About 62% of those with infertility under 35 give birth following IVF. For those over the age of 40, the success rate drops to less than 18% (CDC, 2018). If you cannot conceive using your own eggs, there are other paths to parenthood, including fertility treatment using donor eggs.

Seeking help from a fertility specialist

Fertility specialists can get a rough idea of your ovarian reserve (how many eggs you have left) based on a number of tests, including:

Your antral follicle count—how many follicles (fluid-filled sacs within the ovary that house developing eggs) they can see during an ultrasound

Blood tests that check your antimullerian hormone (AMH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)

Although these tests can tell you whether your ovarian reserve is in the normal range for your age, they do not predict your likelihood of getting pregnant (George, 2010).

A study of 750 women between 30–44 actively trying to conceive found that those with signs of low ovarian reserve conceived at a similar rate to those with average ovarian reserves (Steiner, 2017). Although these tests don’t predict your likelihood of getting pregnant, a diminished or low ovarian reserve often means fewer eggs retrieved during egg freezing or assisted reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures (Ishii, 2019).

While it might not feel like time is on your side, you have a chance at natural conception as long as you’re still ovulating. And even if you’re no longer ovulating, you can still get pregnant with IVF if you’ve frozen your own eggs or gotten donor eggs. Advancements in fertility medicine continue to open new pathways to parenthood, even with age-related challenges with getting pregnant.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018) Assisted reproductive technology fertility clinic success rates report. Atlanta (GA): US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2020 . Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/art/pdf/2018-report/ART-2018-Clinic-Report-Full.pdf

Eijkemans, M. J., Van Poppel, F., Habbema, D. F., et al. (2014). Too old to have children? Lessons from natural fertility populations. Human Reproduction , 29 (6), 1304-1312. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu056. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/humrep/article/29/6/1304/625687

Faddy, M. J. & Gosden, R. G. (1995). Physiology: A mathematical model of follicle dynamics in the human ovary. Human Reproduction , 10 (4), 770-775. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136036. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7650119/

Franasiak, J. M., Forman, E. J., Hong, K. H., et al. (2014). The nature of aneuploidy with increasing age of the female partner: a review of 15,169 consecutive trophectoderm biopsies evaluated with comprehensive chromosomal screening. Fertility and Sterility , 101 (3), 656-663. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.11.004. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24355045/

Geiger, C. K., Clapp, M. A., & Cohen, J. L. (2021). Association of prenatal care services, maternal morbidity, and perinatal mortality with the advanced maternal age cutoff of 35 years. JAMA Health Forum , 2 (12), e214044-e214044. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4044. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2786896

George, K. & Kamath, M. S. (2010). Fertility and age. Journal of Human Reproductive Sciences , 3 (3), 121. doi:10.4103/0974-1208.74152. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3017326/

Ishii, R., Tachibana, N., Okawa, R., et al. (2019). Different anti-Műllerian hormone (AMH) levels respond to distinct ovarian stimulation methods in assisted reproductive technology (ART): Clues to better ART outcomes. Reproductive Medicine and Biology , 18 (3), 263-272. doi:10.1002/rmb2.12270. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/rmb2.12270

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). (2012). Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility , 98 (5), 1103-1111. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.048. Retrieved from https://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(12)00701-7/fulltext

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). (2021). Optimizing natural fertility: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility , 117 (1), 53-63. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.10.007. Retrieved from https://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(21)02130-0/fulltext

Rothman, K. J., Wise, L. A., Sørensen, H. T., et al. (2013). Volitional determinants and age-related decline in fecundability: a general population prospective cohort study in Denmark. Fertility and Sterility , 99 (7), 1958-1964. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.040. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23517858/

Steiner, A. Z., Pritchard, D., Stanczyk, F. Z., et al. (2017). Association between biomarkers of ovarian reserve and infertility among older women of reproductive age. JAMA , 318 (14), 1367-1376. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.14588. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29049585/

Wesselink, A. K., Rothman, K. J., Hatch, E. E., et al. (2017). Age and fecundability in a North American preconception cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology , 217 (6), 667-e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.09.002. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5712257/