Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Content warning: This article contains medical education around serious birth defects that might be upsetting or triggering for some. Hyperlinked sources may show graphic imagery.

One of the most devastating things a pregnant person may hear is that there's something "abnormal" about their pregnancy. These abnormalities range from mild (more common) to severe (more rare), and some may lead to very difficult decisions about what to do next. Whatever decisions are made, the process of getting there can be filled with stress and painful emotions.

At Modern Fertility, we provide clinically accurate information to help you prepare for the possibilities when trying to conceive or pregnant — even when the topics are as emotionally complex as this one. Our hope, as always, is to bring you a neutral resource you can turn to with any of your questions or concerns as you navigate your reproductive timeline.

Here are the biggest takeaways from this article:

Fetal anomalies are commonly referred to as birth defects, and 2%-3% of pregnant people might receive one of these diagnoses. Some anomalies may lead to miscarriage (chromosomal abnormalities account for approximately 50% of miscarriage) — others may occur in pregnancies that continue to term.

Not all birth defects have known causes, but there are some factors associated with increased or high risk.

Most fetal anomalies will be detected during screening tests or ultrasounds in the first or second trimesters, but some may not be until third-trimester anomaly scans.

A fetal anomaly is considered "incompatible with life," now often referred to as "life limiting," if infant survival rates or quality of life are predicted to be very low. Common examples of these conditions are anencephaly, more severe forms of holoprosencephaly, hydranencephaly, renal agenesis, thanatophoric dysplasia, and triploidy.

In general, if a pregnant person is faced with a fetal anomaly that's considered "life limiting," they may decide between terminating the pregnancy, continuing the pregnancy with palliative comfort care, continuing the pregnancy with intensive care, or waiting until delivery to fully assess the situation.

There are no right or wrong decisions in response to fetal anomalies. Care teams are there to help people make the right choices for them.

Before going any further, we want to reiterate that what we're touching on in this article may be tough to read. Take a break if you need to — and know that our Modern Community is there for you whenever you're looking for some real-time support.

What are fetal anomalies?

Between 2% and 3% of pregnant people get news of a fetal anomaly (also called a congenital anomaly, fetal abnormality, or birth defect) after prenatal screening tests. In the US, the Boston Children's Hospital identifies structural anomalies like heart defects, cleft lip/palate, and the neural tube defect (NTD) spina bifida, as well as Down syndrome, as the most common fetal anomalies.

Some fetal anomalies are more serious than others, and some can even be prevented: According to the FDA, diets adequate in folate may reduce the risk of neural tube defects (one type of fetal anomaly).*

What causes fetal anomalies?

The World Health Organization reports that around 50% of fetal anomalies don't have one specific cause. But they do highlight several possible causes and risk factors:

Single gene defects: Disorders caused by a single gene on the first 22 chromosomes that only show up if there are two copies of the genetic variant (e.g., cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia).

Chromosomal disorders: Disorders where one or more chromosomes are missing, duplicated, or partially transferred to another location (and the cause of about 50% of miscarriages).

Multifactorial inheritance: Genes are the main factor but other non-genetic factors, like environment or nutrition, are also at play.

Environmental teratogens: Toxic chemicals found in the environment.

Micronutrient deficiencies: Too low levels of necessary micronutrients for growth and development.

WHO adds that other factors may also lead to increased risks of birth defects and anomalies, like carrying a pregnancy at a later maternal age or living in a low or middle-income country — the latter due to less access to prenatal screening, prenatal care, and more exposure to infections and other chemicals or contaminants.

What steps can you take to decrease the risk of being diagnosed with a fetal anomaly?

Since many fetal anomalies don't have a known cause, there's no way to completely prevent them. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend the following steps to reduce the risk as much as possible:

Take prenatal vitamins with folate before and during pregnancy: Like we mentioned in the first section, the FDA says that diets adequate in folate may reduce the risk of neural tube defects (a common type of fetal anomaly).*

See your healthcare provider regularly: Go to your provider for a preconception appointment (before pregnancy) and contact them as soon as you get a positive pregnancy test result to set up prenatal care. The CDC's recommendations also include managing diabetes during pregnancy, which a provider can help with, and talking with a provider about healthy lifestyle habits.

Check in with your provider about medications and vaccines: While some medications aren't safe for pregnancy, always talk to your healthcare provider about the possible risks of your prescriptions before stopping them. When you're with your provider, also make sure you're up to date on vaccines that are safe during pregnancy (like the flu shot, Tdap vaccine, and the COVID-19 vaccine).

Avoid substances and conditions that are known to be harmful: This includes alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, other recreational drugs, and getting overheated (through fever or exposure to high temperatures, like hot tubs). For some people, quitting substances can be really challenging — so if you need support, talk to your healthcare provider about treatment options.

Prevent the infections you're able to prevent: The CDC advises washing your hands with soap and water, limiting your contact with the saliva and urine of babies and young children, avoiding unpasteurized milk and related products, avoiding dirty cat litter, staying away from rodents and their droppings, getting tested for and protecting yourself against sexually transmitted infections (STIs), avoiding people who you know have infections, and getting tested for group B streptococcus.

Another preconception consideration is genetic carrier screening. Although genetic carrier screening is not mandatory in the US (or included in CDC's recommendations), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all people trying to get pregnant or currently pregnant be given the option. Genetic carrier screening, which focuses on conditions that are caused by a known single gene, can tell you and your partner whether you carry certain recessive genetic variants that you could pass on to biological children, and the probabilities of your children having certain genetic conditions. It can be done through your doctor or direct-to-consumer tests.

How are fetal anomalies diagnosed?

Throughout pregnancy, healthcare providers will run a variety of genetic tests, blood tests, and ultrasounds to check in on fetal development and health. For the most common fetal anomalies, screenings and ultrasound scans in the first and second trimesters will lead to prenatal diagnosis. But one prospective study of 52,400 pregnancies found that almost a quarter of fetal anomalies were discovered during ultrasounds at around 35-37 weeks gestation (the third trimester). This means that while most anomalies will be detected earlier in pregnancy, some may not be until much later on.

Here's a brief overview of the fetal anomaly screenings and tests that may be performed during each trimester:

First trimester:

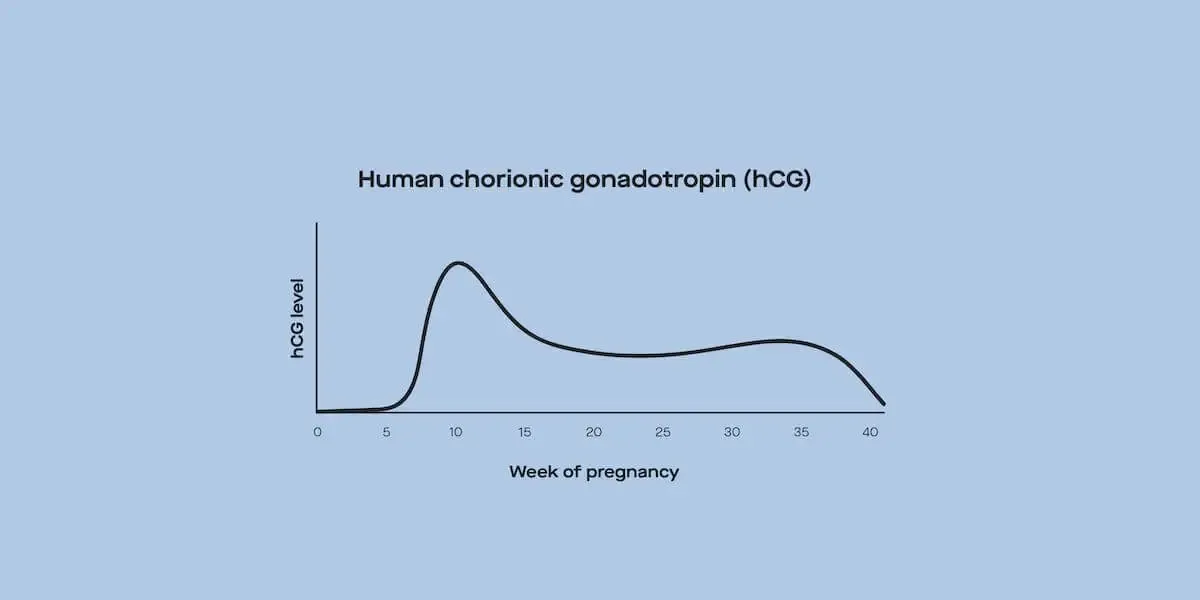

Prenatal genetic screening tests, including maternal serum analytes, noninvasive prenatal testing (often called NIPT or cell-free DNA screening), and carrier screening.

Prenatal genetic diagnostic tests for "abnormal" screening results, including chorionic villus sampling (CVS).

Second trimester:

Prenatal genetic diagnostic tests for "abnormal" screening results, including amniocentesis.

More prenatal genetic screening tests, including maternal serum analytes.

Third trimester: Toward the end of pregnancy, doctors may check the position of the fetus via ultrasound in preparation for birth and delivery. This ultrasound is where some anomalies (up to a quarter) may be discovered.

What fetal anomalies are considered "life limiting"?

While there's no agreed-upon definition of which fetal anomalies are "incompatible with life" or "life limiting," these phrases are typically used to describe birth defects with low survival rates or low quality of life. The following anomalies are commonly put into this category:

Anencephaly: Anencephaly is a very serious birth defect in which an infant is born without parts of their brain or skull. The incidence of anencephaly in the US is about 1 in every 4,600 births. As of right now, there's no treatment for anencephaly — and the majority of infants born with it will live for only a few weeks.

Holoprosencephaly: In cases of holoprosencephaly, there's malformation in the forebrain (a part of the fetal brain develops into parts of the adult brain) — it develops without the expected connection between the two halves of the brain. While the majority of pregnancies with holoprosencephaly end in miscarriage, the birth defect occurs in about 1 in 10,000 births in the US. Infants born with the most severe type of holoprosencephaly, alobar holoprosencephaly, may only live up to six months. Those with more mild effects might live past a year.

Hydranencephaly: This extremely rare central nervous system disorder is marked by an enlarged head, neurological deficits, and missing portions of the brain. About 1 in 250,000 infants are born with hydranencephaly. Many of them will only live about a year.

Renal agenesis: In renal agenesis, an infant is born without one (unilateral) or both (bilateral) kidneys. Unilateral renal agenesis happens in about 1 in 2,000 births, while bilateral happens in about 1 in 4,000. Infants born with unilateral renal agenesis may lead normal lives, but those born with bilateral renal agenesis are unlikely to survive without treatment (which is currently still experimental).

Thanatophoric dysplasia: This is a severe but very rare genetic skeletal disorder where an infant is born with very short limbs, folds of extra skin on their arms and legs, and often a narrow chest, short ribs, and underdeveloped lungs. In the US, about 0.36-0.60 in 10,000 infants are born with thanatophoric dysplasia. Most children with the disorder die shortly after birth, but some have lived longer with extensive medical support.

Triploidy: Triploidy is a rare chromosomal abnormality in which an infant is born with 69 chromosomes instead of the typically inherited 46. This abnormality occurs in about 1%-3% of pregnancies. Most fetuses won't make it to birth, but those that do often die shortly after. Some people born with triploidy have survived to adulthood (though with developmental delay, seizures, and other issues).

Even considering the fetal anomalies that are "incompatible with life" or "life limiting," it's important to note that not all infants will have the same outcomes — and as modern medicine advances and evolves, new treatment options may extend or improve the lives of infants born with certain anomalies.

What can you do if you get diagnosed with a "life-limiting" fetal abnormality?

"The tough thing with anomalies is we can almost never definitively tell you if a baby will survive," explains Dr. Ukachi Emeruwa, MD, MPH, a Maternal-Fetal Medicine fellow in Columbia University Irving Medical Center’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. This makes deciding what to do incredibly challenging — on top of what's already often a very painful situation. "Every family has their threshold, what they envision as an appropriate quality of life," she adds. "It’s a lot of stress for families, what they can withstand and what support they have."

Because of the limitations of many people's health insurance coverage, pregnant people who've had a fetal anomaly diagnosis that's considered "life limiting" or "incompatible with life" may turn to their healthcare providers for support instead of seeking out additional providers. Dr. Emeruwa says that hospital neonatal palliative care teams are equipped to guide parents through this difficult decision, including whether or not to intervene in the pregnancy, when to intervene, and what impact any interventions might have on future fertility.

So, what are the options a pregnant person might discuss with their healthcare provider or a neonatal palliative care team after a "life-limiting" or "incompatible with life" diagnosis of fetal anomaly?:

Terminate the pregnancy: Up to 90% of people in these situations may choose to terminate their pregnancies, but that doesn't mean healthcare providers will necessarily recommend termination of pregnancy. “The only times in which we recommend abortion in desired pregnancies is when we think that it is putting mom’s life at risk and we don’t think there will be any benefit to the baby,” says Dr. Emeruwa. Depending on the trimester, some terminations will be extremely difficult and expensive to obtain. Only a handful of clinics in the US provide abortion care in the third trimester — and many states have regulations limiting care to earlier gestational age.

Continue with the pregnancy, give birth, and choose comfort care: Perinatal palliative comfort care prioritizes comfort and quality of life for infants born with life-limiting conditions. Pregnant people can work with their provider team to establish an individualized care plan.

Continue with the pregnancy, give birth, and opt for intensive care: If this decision is made, the care team will do everything in their power to support the infant's survival. In some cases, that may mean choosing to deliver earlier or through cesarean section (C-section), the latter of which could mean more C-sections in future pregnancies.

Assess the infant after delivery but opt for comfort over intensive care: For some pregnant people and parents, a middle ground between comfort and intensive care may be desired. They may choose to wait until delivery to see exactly what the infant's outcome may be, but they may also draw the line at intensive care after certain inventions (like intubation or CPR) and switch to comfort care.

How does one even begin to navigate this incredibly difficult decision? "Gather as much information as possible, be sure you feel safe and supported by your medical providers, and cultivate a compassionate multidisciplinary care team — this could include a therapist, doula, family, and any other supports who will help you make the best choice," says Modern Fertility staff therapist Meghan Cassidy, LCSW-C. "A wide array of difficult emotions are likely to occur no matter what, but people work through unimaginable experiences best when we have choice, support, and care."

What can you do to take care of your mental health when dealing with a fetal anomaly?

No matter what decision is made regarding a fetal anomaly, getting to that decision — and coming to terms with it — can feel like an enormous emotional weight. Throughout the process, it's important to hold space for your mental health and prioritize your well-being.

Below, Meghan (our staff therapist) shares her tips for dealing with emotions and mental health while managing decisions around fetal anomalies.

Know that conflicting emotions are okay.

"You may have conflicting emotions about this diagnosis — that is normal and okay. You may be angry or upset that your baby has a fetal anomaly, but it does not mean that you don’t also love or want your baby. Allow for the word ‘and’ to be present as you process your emotions about this diagnosis. I feel happy to be pregnant ‘and’ heartbroken about the diagnosis. I know there is nothing I could have done to prevent this, ‘and’ I feel like somehow there is more I should have done. It takes practice to hold conflicting emotions, but it allows for the whole range of our experience to be felt and not to get stuck. The only way to move through the hard is to move through it."

Try and process each emotion as it comes up.

"Try to allow and process each emotion as it arises, doing so will allow hard emotions to pass more readily. Where we can get stuck most often is in the secondary emotions, how we are judging our original feelings. For example, you may feel resentful of the diagnosis, but then experience guilt for feeling resentful. Know that any emotion that comes is okay, and allowing it to be part of your experience will also allow it to pass through you."

Grieve however you see fit.

"You get to grieve that your baby may not have the life you thought they might have. You get to grieve that your life might change in ways you never expected. Grieving does not mean you are not grateful for your child. The grief will not be linear either — it will intensify and lessen in both predictable and unpredictable ways."

Get the support you need.

Finally, Meghan recommends reaching out to support groups, therapists, doulas (sometimes called "bereavement doulas"), or other providers when you need some assistance working through these painful emotions. You can always follow up with your healthcare provider about their recommendations — if you're working with a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, they may have a mental healthcare team designated for these difficult situations.

If you have trouble finding the right resources for you, here are some options depending on your preferences:

Online resources and communities:

Phone support lines:

Connect & Breathe (judgment-free after-abortion talk line)

Faith Aloud (faith-based)

Therapist finders:

This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Ukachi Emeruwa, MD, MPH, a Maternal-Fetal Medicine fellow in Columbia University Irving Medical Center’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

*This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.