Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

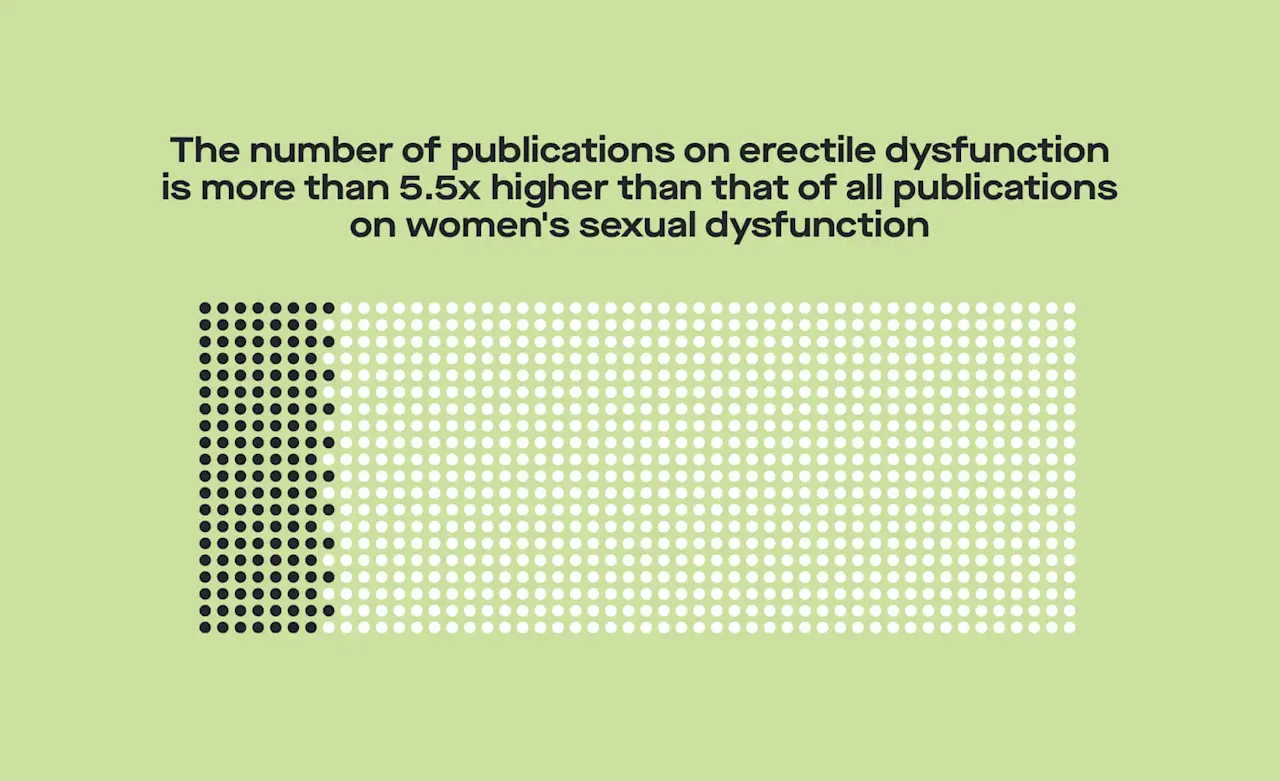

Gender biases in medicine are nothing new. There's no exception when it comes to studying women’s sexual desire.

(If you’re curious to learn more, John Oliver’s overview of the topic is a fantastic summary!)

In the past few decades, scientists have tried to play catch-up and uncover the hormonal drivers of women’s sexual desire. While we’re closer than we’ve ever been to solving the puzzle (yay), there are still many lingering myths and gaping knowledge holes (boooo).

The more we understand the role hormones play in sexual desire, the more we’ll understand things like changes across our menstrual cycles, the impact of different types of contraceptives, and how our sex drive might change as we get older.

Here, we’ll walk you through the history behind women’s sexual desire research, some recent findings, and what we’ve still got left to learn.

But first, a disclaimer: Studying women’s sexual desire is complicated

The scientific, systematic study of humans is always complicated, and this is especially the case when it comes to psychology and behavior. When studying animals like mice or nonhuman primates, we can control their environments: when and what they eat, what their living spaces look like, who they can spend time with, and sometimes even their hormone levels. By controlling all these variables, we can isolate the specific thing we’re interested in, and manipulate just that one thing (while holding everything else constant) to see what effect that manipulation has.

When it comes to humans living in their own complex environments, this isn't really possible. With less experimental control comes less precision and more noise in the data.

When it comes to sexual desire specifically, there’s also the whole problem of how we even define it. Do we just ask women how turned on they are? Do we ask how often they have sex? Do we try to get at sexual desire through some sort of experimental task, like by putting women in a brain scanner and seeing what parts of the brain light up, and how much, when they view sexual images?

Your guess is as good as ours as to what the "best" method is; as of now, those of us researching this topic try to use as many methods as possible.

With those caveats in mind, let’s dive into the science.

Takin’ it back: The (ridiculously abbreviated) history of hormones & sexuality in women

Like in much of medicine, someone accidentally stumbled upon the link between reproductive hormones and sexual desire. Testosterone was first isolated and synthesized in the 1930s, and started getting prescribed for a wide range of conditions. Some women who were taking doses of testosterone that far exceeded what is considered "normal" noticed some pretty unexpected side effects, like facial hair growth and a deeper voice—but they also noticed increases in sexual desire. And just like that, the myth that testosterone is the prime driver of sexual desire in women was born.

Over the next 30-40 years, we got more insight into how testosterone and estrogens like estradiol (our estrogen of choice here at Modern Fertility) change across the menstrual cycle, and how those changes relate to psychology and behavior. Estradiol increases up to 800% around ovulation (there’s also a second, lower peak after ovulation in the luteal phase), while testosterone increases up to 150% in that same time period.

Scientists also noticed that during ovulation (when both estradiol and testosterone are high), women were more likely to initiate sexual behavior, were more likely to engage in non-partnered sexual behavior, and reported higher levels of sexual desire. But because both of these hormones increase around this time, we didn’t know to what extent each had an influence on women’s sexuality individually. Cue lots of guessing, throwing hands up in the air, and continuing to treat women with super high doses of testosterone.

Fast forward to the 2000s (yes, you read that correctly—over 60 years after testosterone was first prescribed to women), and we finally saw some of the first studies that measured natural levels of reproductive hormones and sexual behavior and desire in women.

Myth busting the relationship between sexual desire and hormones

The last 20 years have seen an influx of studies that do what we should have been doing all along: measuring blood or saliva levels of testosterone and estradiol in women, and seeing how those correlate with sexual behavior and desire. Better late than never?

Though there have been several studies looking at hormones and sexual desire, our favorite is from 2013, titled Hormonal predictors of sexual motivation in natural menstrual cycles This was the first study to use daily measures of estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone (another reproductive hormone that is seen in especially high concentrations during the second half of your cycle). This study also simultaneously measured women’s sexual desire and behavior across full menstrual cycles.

The strongest predictor of sexual behavior in this study? Whether or not it was a weekend (are you shocked?). Hormones had nothing to do with it.

The predictors of sexual desire, however, were a bit different—progesterone had a negative influence, meaning when progesterone went up, sexual desire went down; and estradiol had a positive influence, meaning when estradiol went up, sexual desire went up. Testosterone had nothing to do with it. (Myth. Busted.)

Bottom line: Testosterone’s out, estradiol and progesterone are in.

The early myth of testosterone and women’s sexual desire originated from observations of side effects in women receiving crazy high doses of testosterone. Later work has found that in women with reproductive hormones within the normal range, it’s more likely estradiol and progesterone that affect sexual desire and behavior.

But current FDA-approved treatments for women’s sexual dysfunction don’t reflect that. And if you’re thinking that is totally crazy, you aren’t alone. Current medications approved for what’s called “hypoactive sexual desire disorder” were designed for different conditions, but just so happen to have positive effects on women’s sex drive.

If these treatments aren’t based on what we know about the hormonal drivers of women’s sexual desire, how do they work? How effective are they? Should we be rejoicing over what medication manufacturers want us to call ‘the female Viagra,’ or should we stay a little skeptical? Stay tuned to the Modern Fertility blog for more on this soon.

Here’s why we need more studies on women’s sexual desire

One study isn’t enough for us to say we’ve got it all figured out, regardless of how methodologically stellar that one study is. We still don’t know whether hormones affect different types of sexual desire—maybe hormones affect the primal, hit-it-and-quit-it type of sexual desire in a different way than the loving and sensual type of sexual desire.

Also, while we’re pretty sure that hormonal changes across a woman’s menstrual cycle have an impact – especially when it comes to estradiol and progesterone – we aren’t yet sure what role this plays from woman to woman. Some women produce more or less of reproductive hormones (like estradiol and progesterone) than other women, and these differences are totally normal and natural. But the question remains: do women who produce higher estradiol also have a higher sex drive, on average, than women who produce less estradiol? We still haven’t figured out what effects (if any!) average levels of reproductive hormones may have on women’s sexuality.

Finally, we don’t know why these hormone-driven changes in sexuality exist. While many theories have been proposed (check out this paper by yours truly if you want to get into the weeds of this a bit), we still don’t know which ones are most likely. But, rest assured that we’re doing our best to figure it out.

Really want to dive deeper on this topic?Here are a few of our favorite studies.

Arlsan et al. (2019). Using 26,000 diary entries to show ovulatory changes in sexual desire and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Cappelletti & Wallen (2016). Increasing women's sexual desire: The comparative effectiveness of estrogens and androgens. Hormones and Behavior.

Wallen et al. (1984). Periovulatory changes in female sexual behavior and patterns of ovarian steroid secretion in group-living rhesus monkeys. Hormones and Behavior.

Motta-Mena & Puts (2017). Endocrinology of human female sexuality, mating, and reproductive behavior. Hormones and Behavior.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.