Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Many people only think about their menstrual cycle when they have their period about once a month. Sure, we all know the body goes through a whole cycle of hormonal changes throughout the month, but many women probably don’t give the rest of the cycle much thought unless there are issues.

The menstrual cycle is a supremely complex system, though, involving the delicate production and interaction of hormones. If these hormones aren’t produced in the correct amounts during your cycle, you may have trouble with your fertility. One of these potential problems is called a luteal phase defect (LPD).

What is a luteal phase defect?

In a luteal phase defect (also called a luteal phase deficiency), a part of your ovary called the corpus luteum starts to break down earlier than usual in the menstrual cycle. This usually happens when your body has low progesterone levels or your uterus can’t respond appropriately to the progesterone that is made. This can result in problems becoming and staying pregnant (Kirkendoll, 2021).

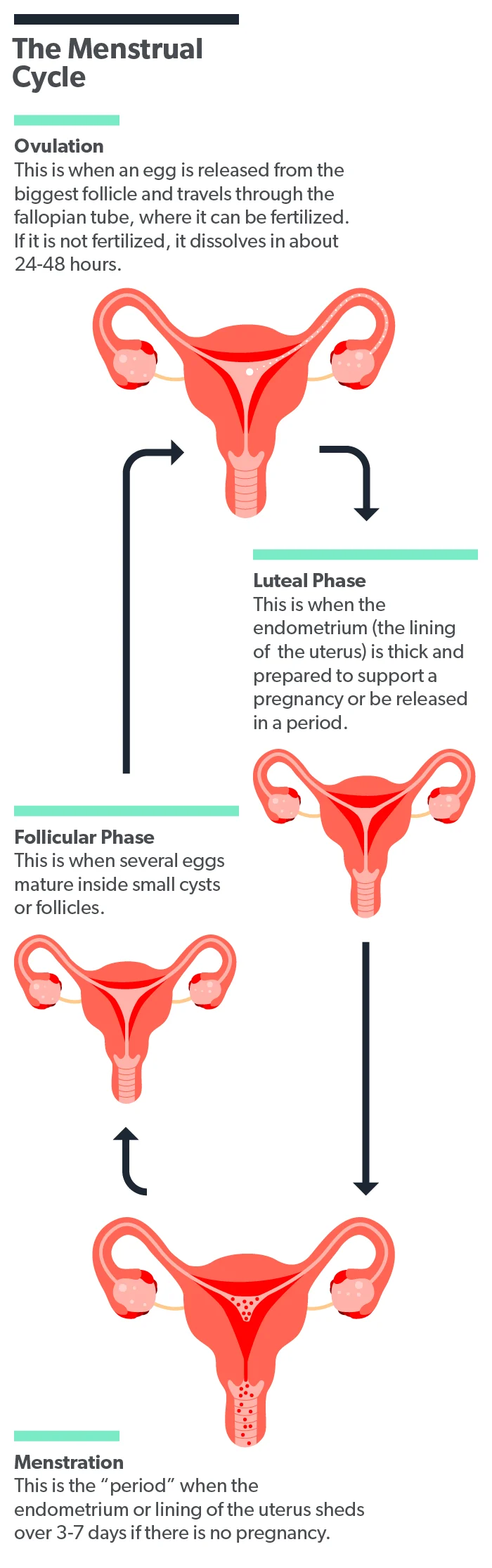

The luteal phase is the second phase of the menstrual cycle. When there is no luteal phase defect, it starts on day 14 of your cycle, after ovulation, and continues until day 28. During this stage, a hormone called luteinizing hormone (LH) encourages the corpus luteum to produce more of the sex hormone progesterone (Thiyagarajan, 2021).

The increased progesterone levels tell your uterine lining (called the endometrium) to get ready to receive a fertilized egg. The endometrium then develops more blood vessels and produces more mucus. Progesterone also increases your basal body temperature (Thiyagarajan, 2021).

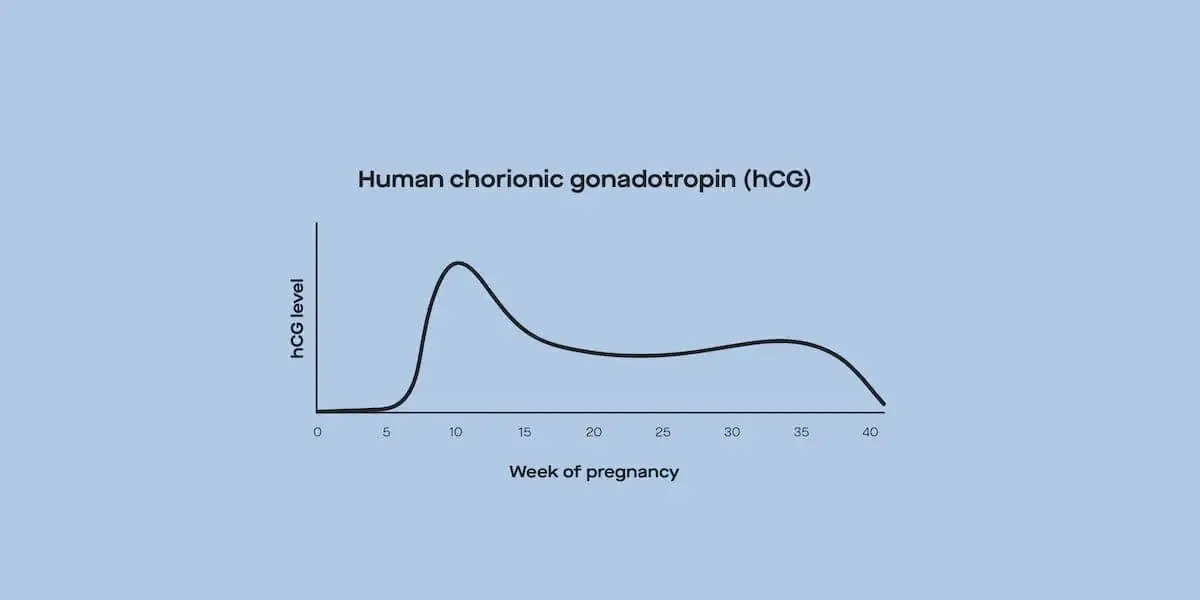

As the luteal phase ends, LH levels start to fall, and so does the amount of progesterone being produced. If a fertilized egg implants in the uterus during this time, the placenta ensures that your progesterone levels will stay elevated to help maintain the pregnancy. If there is no fertilized egg, your hormone levels will continue to drop, and your body will shed the endometrium from your body (Thiyagarajan, 2021).

What causes a luteal phase defect?

Progesterone helps prepare your uterus for pregnancy and supports the early pregnancy until the placenta develops. If you have a short luteal phase, you may not have enough progesterone to support your endometrium, which could result in trouble getting pregnant or early pregnancy loss (recurrent miscarriage) (Piltonen, 2019).

Luteal phase defects are thought to be common conditions, although researchers haven’t agreed on how common or whether they are definitely a cause of infertility (Palomba, 2015).

While medical researchers don’t know exactly what causes LPD, it is thought to be connected to several health conditions that can affect the hormone levels in your body, such as (Palomba, 2015):

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

Obesity

Thyroid disorders

High prolactin levels

Problems with your pituitary gland

Healthcare providers think that treating these conditions can help improve levels of progesterone and pregnancy rates (Palomba, 2015).

What are the signs of a luteal phase defect?

The signs of luteal phase defect can be subtle. You may not even notice them unless you have trouble getting and staying pregnant. There are no official criteria to diagnose LPD, but your provider might suspect it if you experience abnormalities such as (Mesen, 2015; Piltonen, 2019):

Shorter than average menstrual cycles

Spotting in between your periods

Infertility or recurrent early pregnancy loss

According to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), there is no official test or criteria to diagnose a luteal phase defect (Mesen, 2015).

Your healthcare provider might test your hormone levels or perform a pelvic ultrasound to try to find a cause for your fertility problems (Mesen, 2015).

In the past, providers performed an endometrial biopsy when they suspected a luteal phase deficiency. This was a small surgery where the provider would take a tiny sample of the lining of your uterus. Further medical studies showed that this procedure wasn’t actually very accurate, so providers stopped using it (Mesen, 2015).

Can you get pregnant with a luteal phase defect?

You may be able to get pregnant and deliver a baby without any trouble, even if you have a luteal phase defect. LPD has been associated with a higher risk of infertility and miscarriages, but not all researchers agree that LPD is the cause of these issues (Palomba, 2015).

Reproductive specialists recommend having a workup to identify any underlying health conditions that could be affecting your menstrual cycle. These should be treated first to see if they help normalize your menstrual cycle (Palomba, 2015).

If you’re still having fertility issues after this, your healthcare provider can help you explore other treatment options, such as progesterone supplements or assisted reproduction technologies (Palomba, 2015).

How do you treat luteal phase defects?

Since medical researchers don’t yet agree about what causes luteal phase defects or how to diagnose them, it’s not surprising that they also don’t agree on the best way to treat them.

Reproductive specialists do see eye to eye on the first step of LPD treatment, though—namely, identifying and treating any underlying health conditions. Illnesses such as thyroid disease can affect the connections between your brain and your reproductive system. This can change how your body produces the hormones you need to get pregnant (Mesen, 2015).

If there are no underlying conditions, or if problems with fertility remain after treatment, there are other options. However, these options don’t currently have strong scientific evidence to support them (Palomba, 2015).

The first strategy often used is to stimulate ovulation with medications such as (Mesen, 2015):

Clomiphene citrate

Letrozole

Injectable gonadotropins such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone, or human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)

The second luteal phase defect treatment involves using progesterone supplements to boost the levels in your body. These can be given as suppositories, creams, or injections. This is also commonly used during assisted reproductive technology treatment to support the luteal phase. However, more research is still needed to find the best delivery method and timing of the supplement (Mesen, 2015).

Another treatment that has been touted to help with LPD is taking large doses of vitamin C or ascorbic acid. Vitamin C has long been associated with fertility. Your body uses large amounts of the vitamin to help make the collagen in tissues in your ovaries that regulate your menstrual cycle. Researchers initially thought that taking vitamin C supplements might encourage your body to ovulate and produce more progesterone (Griesinger, 2002).

However, a large study of women undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) found that taking a high-dose vitamin C supplement didn’t improve the chances of a successful pregnancy after embryos were transferred into the uterus (Griesinger, 2002).

If you're having trouble getting pregnant or are experiencing early pregnancy losses, talk to your healthcare provider. They can help you find out if you have any underlying medical conditions that might cause a luteal phase defect and provide you with a referral to reproductive endocrinology, the medical specialty that most commonly treats fertility issues.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Griesinger, G., Franke, K., Kinast, C., Kutzelnigg, A., Riedinger, S., Kulin, S., et al. (2002). Ascorbic acid supplement during luteal phase in IVF. Journal Of Assisted Reproduction Aand Genetics, 19 (4), 164–168. doi: 10.1023/a:1014837811353. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3455656/

Kirkendoll, S. D. & Bacha, D. (2021). Histology, corpus albicans. [Updated 2021, May 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Dec. 27, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545270/

Mesen, T. B. & Young, S. L. (2015). Progesterone and the luteal phase: a requisite to reproduction. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 42 (1), 135–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2014.10.003. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4436586/

Palomba, S., Santagni, S., & La Sala, G. B. (2015). Progesterone administration for luteal phase deficiency in human reproduction: an old or new issue?. Journal of Ovarian Research, 8 , 77. doi: 10.1186/s13048-015-0205-8. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4653859/

Piltonen, T. T. (2019). Luteal phase deficiency: are we chasing a ghost? Fertility and Sterility, 112 (2), 243-244. Retrieved from https://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(19)30557-6/fulltext

Thiyagarajan, D. K., Basit, H., & Jeanmonod, R. (2021). Physiology, menstrual cycle. [Updated 2021, Sep 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Dec. 27, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500020/