Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Though reusable menstrual cups (sometimes called soft cups or diva cups) and discs have been around in various shapes and forms since at least the 1860s, their use has become mainstream within the past decade.

Lately, menstrual cups and discs, which are primarily designed to hold menstrual blood (often as an eco-friendly and less painful alternative to tampons), are increasingly getting more attention for a second use: to boost chances of conception and help you "get pregnant faster."

The logic behind the buzz? If used as a cup to place and keep ejaculated sperm or donated sperm closer to the opening of the cervix, menstrual cups and discs could, in theory, increase chances of conception when chances of getting pregnant are highest (the five days before and the day of ovulation).

Does this theory hold true when we look at real-world outcomes? We just don't know yet: As of right now, there's no clinical data to suggest that people who use a menstrual cup or disc get pregnant at higher rates, or more quickly, than people who don’t use them. (We're hoping to see some data here soon.)

Before we dive into the likely origin story of this theory and the data we have around it, a quick note: Fertility science is always evolving, but there are big gaps in the research (and in women's health research in general). Even if something isn't validated by large-scale, randomized trials, that doesn't mean it can't have benefits for you as an individual. Ultimately, personal experience can be just as valuable as scientific evidence.

Modern Fertility’s medical advisor, Dr. Jane van Dis, says that both heterosexual and lesbian couples have been using menstrual discs off-label for this purpose for years. There is no data to show that it’s more effective, but also no data to show harm. Especially for couples using sperm donation, using a menstrual disc can, conceivably, be more efficacious than simply placing sperm in the vagina alone.

Where did the menstrual cup theory come from?

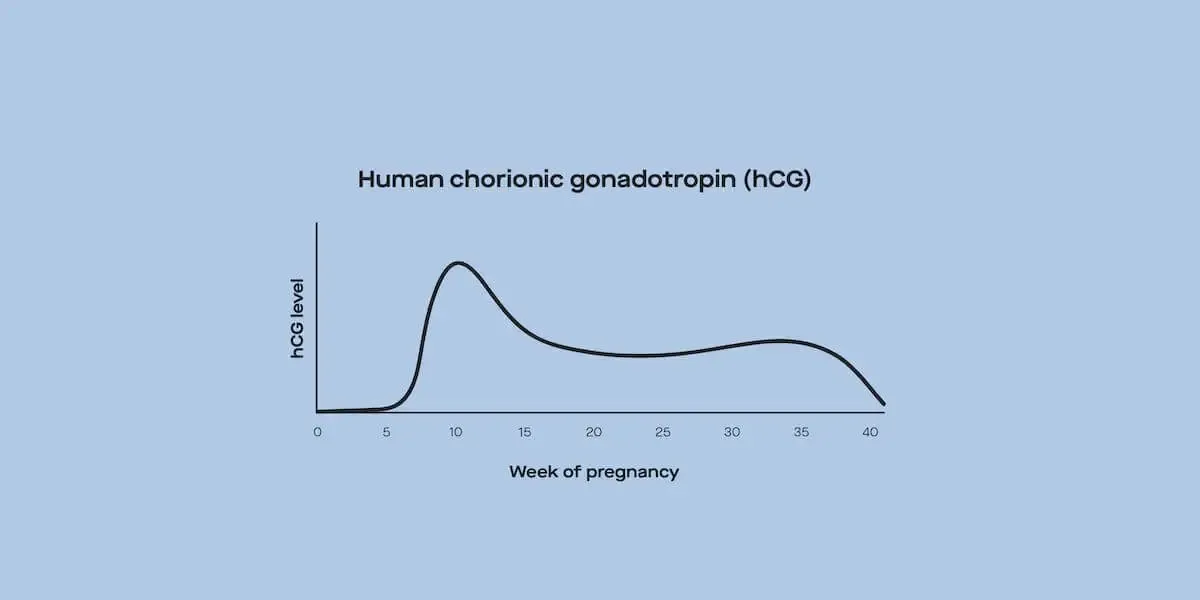

There are so many things that need to go right for a pregnancy to occur, and one of the earliest and most important steps is sperm getting to an egg for fertilization. To do this, sperm need to make it into the vagina, past the cervix, into the uterus, and to the fallopian tubes where an ovulated egg will be (during cycles with ovulation).

During penile-vaginal intercourse and intracervical insemination (ICI), sperm are deposited near the cervix and make it to the fallopian tubes within minutes. Fertility treatments (like in vitro fertilization, or IVF) bypass the need for sperm to travel beyond the cervix entirely.

In both penile-vaginal intercourse and ICI, the number of sperm that make it to the fallopian tubes is linked to the number of sperm deposited near the cervix. Because of this, in theory, anything that keeps sperm there could increase the number of sperm that make it to the egg and increase the chances of fertilization. This theory is the basis for the idea that menstrual cups and discs — which are designed to be inserted into the vagina, not the cervix — may aid in conception.

The double life of cervical caps

The menstrual device theory could also have been inspired by the history of cervical caps, which were originally introduced as a method of birth control over 100 years ago (though recent data shows that they aren’t particularly great at doing so). These little silicone devices are placed right at the cervix before intercourse and are meant to block ejaculate from getting to the cervix.

At some point (perhaps in the 1980s), some doctors started wondering whether cervical caps could be used for the complete opposite purpose: If they could be used before sex to keep sperm out, could they be used after sex or insemination to keep sperm in to make conception more likely? (Spoiler: As we'll cover in the next section, the findings were mixed.)

Keep in mind that these days, given better forms of contraception, cervical caps have largely been abandoned and many OB-GYNs today have not fitted nor prescribed them.

Is there any data on menstrual cups or discs and conception?

Anecdotes and success stories of people getting pregnant during their first cycle keeping a menstrual cup in after sex or insemination can be found in articles, on Reddit threads, and in online forums. While personal experiences are valuable in their own right and intriguing when it comes to possible evidence of efficacy, they're not always enough to signal that anyone who uses a particular intervention will definitely see the same results — there are just too many potentially confounding factors. (This is why anecdotal reports sit near the bottom of the scientific hierarchy of evidence.)

Until there are systematic studies on menstrual cups/discs and conception, the jury is out on whether we can expect to see a connection for the general population of people who are trying to conceive (TTC). Still, menstrual cups/discs are typically low-cost — if you're interested in trying them out as a tool to help you conceive, there's no real downside.

Even though we don't have clinical data on whether or not menstrual cups/discs can really boost your chances of getting pregnant, we do have reason to believe there's no danger to your body if you use them after sex or insemination (provided you use and clean them as indicated by the manufacturer).

What we do have some data for is cervical cups and conception

As we mentioned earlier, doctors have been wondering about the use of cervical caps for conception for 40-ish years. A few studies were designed to address this quandary and yielded mixed results:

Some found a higher pregnancy rate in people who used cervical caps: One study of people undergoing intracervical insemination (ICI) found that the pregnancy rate per cycle was 5.9% in cycles where cervical caps were *not* used, and 15.2% in cycles where cervical caps were used.

Others did not: Another study of over 600 treatment cycles found pregnancy rates of 7.8% per cycle when a cervical cap was used, and 9.8% per cycle when normal ICI protocols were followed.

More generally, the idea of doing things to keep more sperm in to increase chances of conception isn’t consistently supported. (For example, lying down post-IUI to prevent sperm backflow doesn’t increase your chances of pregnancy, nor do sex positions that might decrease backflow.)

Despite the lack of clear, published evidence to suggest cervical caps are helpful for those who are TTC, several companies have produced direct-to-consumer cervical caps to be used for conception purposes (at least one with FDA clearance as a medical device). It’s important to note that these companies haven't yet provided their own data to prove their products work as advertised, and this is not a requirement for medical device clearance by the FDA.

Even if there was hard-and-fast scientific evidence showing that cervical caps promoted conception, we couldn’t necessarily assume that menstrual cups and discs would have the same effect as cervical caps. This is particularly the case for menstrual cups, which are longer than cervical caps and hold fluid considerably farther away from the cervix.

Bottom line

While there's no scientific data to suggest that methods that prevent sperm backflow from the vagina (like cervical caps, menstrual cups/discs, or positions post-sex or insemination) increase your chances of getting pregnant, with menstrual cups/discs specifically, there are no clear dangers in using them after sex or insemination. (We'll be keeping our eyes out for more research as it comes out.)

Deciding whether or not to give menstrual cups or discs a shot after sex or insemination is between you, your partner (if you have one), and your healthcare provider. What's always worth a shot is doing some informed digging on the fertility of you and your reproductive partner. Are you ovulating regularly? What do semen parameters look like for the partner who has sperm? Knowing key pieces of info like these is crucial to having a conversation with your doctor, who may be able to provide you with more next steps to help you reach your reproductive goals.

Dr. Eva Luo, MD, an OB-GYN and one of Modern Fertility’s medical advisors, says: "When there is no available evidence, I discuss whether an intervention is helpful or harmful for my patient as they try to conceive. If a patient wants to try a menstrual cup for fertility, as long as recommended cleaning procedures are followed, I don't see any harm unless it adds emotional or logistical stress. But keep in mind — there is no available evidence to show it works."

Just for fun: Sperm plugs

The range of reproductive strategies across the animal kingdom is mind-bogglingly impressive, and that’s putting it lightly. Some male animals produce something called a sperm plug (aka mating plug, copulatory plug, or vaginal plug) after sex. In species that produce this, the seminal fluid coagulates after sex and forms a literal barrier in the vagina that prevents sperm from other males from getting to the female’s eggs.

Sperm plugs may have evolved in polygamous species as a form of sperm competition — put differently, males who were able to block the sperm of other males gave their own sperm the upper hand, and were able to have more offspring. Though species closely related to us like chimpanzees do have sperm plugs, we as humans do not.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.