Human speak: Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common female reproductive disorders; affecting approximately 10% or more of women worldwide. PCOS is a big deal because it can lead to infertility and other health problems. The common symptoms associated with PCOS are irregular or no periods and anovulation (meaning you don’t ovulate, or ovulate rarely), increases in androgen hormones (like testosterone) and luteinizing hormone (which usually kicks off ovulation, but is persistently high in women with PCOS), and in some cases, insulin resistance and obesity. There is currently no “cure” for PCOS, just management of symptoms.

This month, a groundbreaking study was published in the journal Nature Medicine that might have found a treatment for this disorder. The research was lead by Dr. Paolo Giacobini at the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research. The authors’ goal was to determine if something in the environment of the womb could be causing PCOS. We have known for awhile that PCOS runs in families (so if your mother or sister has PCOS, you may be more likely to have PCOS because you share genes that are associated with the disorder) but there don’t seem to be enough carriers of these genes to explain the high prevalence of PCOS (again, 10% of women!).

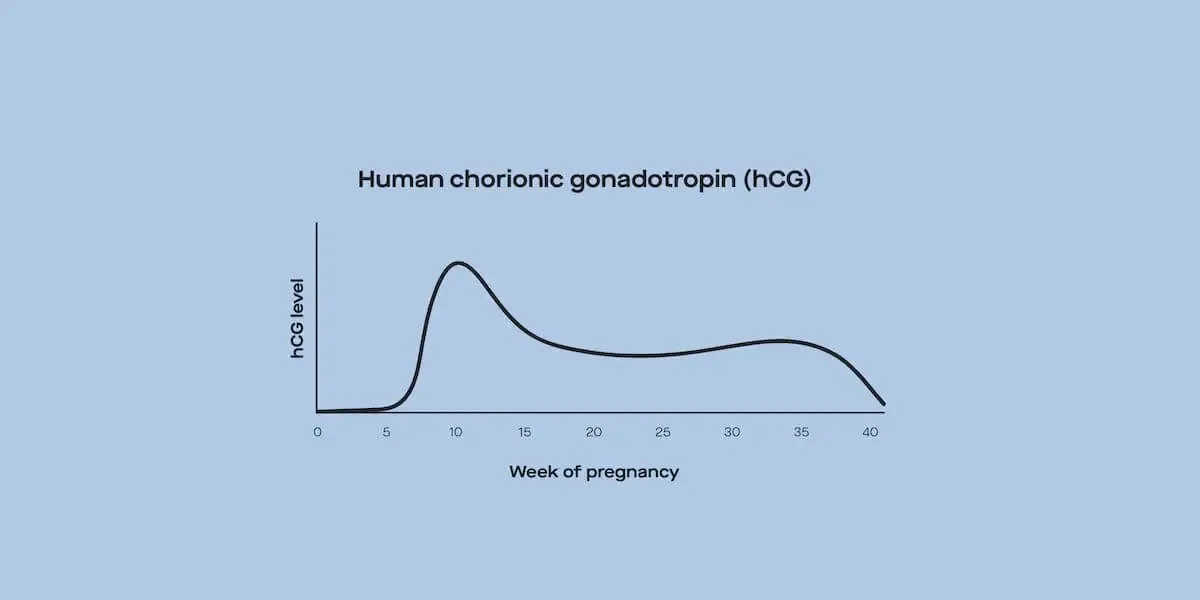

The authors hypothesized that something might be going on in the maternal environment in the womb that was causing PCOS in daughters. To get to the bottom of it, the authors first studied pregnant women by measuring a hormone call anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH). Usually, in pregnancy, a women’s AMH levels decrease. But the authors noticed that in women with PCOS, their levels of AMH did not decrease. The next step was to figure out what these high AMH levels might be doing to the daughters of women with PCOS. The authors used mice to model what was happening with human women by treating pregnant mice with AMH. When they were born, the pups of the treated mice had a lot of the same symptoms as women with PCOS: anovulation, higher testosterone levels, fewer litters and fewer pups per litter, among others. They also noticed that the brains of the mouse mothers treated with AMH produce a lot of another hormone, called GnRH. In fact, they produced three times the amount that control mouse mothers did.

This led the researchers to experiment with blocking the body from responding to this excess GnRH. They treated a separate group of pregnant mice with AMH but also another drug that blocks the body from responding to the higher levels of GnRH (called a “GnRH antagonist”). They followed the daughter pups born to these mothers, and turns out they didn’t develop PCOS-like symptoms! They also wanted to see if they could give GnRH antagonist to daughter pups who had already developed PCOS-like symptoms (because their mothers only received high levels of AMH while pregnant). After treatment with the GnRH antagonist, the daughter pups’ hormone levels started to normalize and they ovulated more than those who didn’t get the antagonist treatment.

This is a really big deal, because GnRH antagonist drugs are pretty common and used to treat some cancer. They are also part of the treatment for women with PCOS who are stimulating their ovaries for IVF and egg-freezing. This study suggests that we might be able to stop PCOS before it develops by treating pregnant women with this drug, and we can potentially use it to treat women who currently have PCOS. It is important to note that there are two commonly recognized types of PCOS, a lean phenotype and an obese phenotype. The authors explain that their mouse model most closely resemble the lean PCOS phenotype, so this treatment might not be able to help all women with PCOS. However, it is still an important step forward.

You can read the full article posted by Nature Medicine here.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.