Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Reintroducing the placenta, the organ that develops during pregnancy to sustain and nourish a growing fetus, to the body by ingesting it after birth can be an important physiological process for some people. But is this practice shown to also have health benefits? And is there any risk to it?

While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advise against placenta encapsulation (the most common way to ingest the placenta) because of the perceived risk of serious infection or toxicity, most research suggests the risks are low in practice. What else does the data tell us? There isn't a ton of scientific evidence to support health benefits from eating your placenta, but anecdotal reports do show positive outcomes.

"In situations where clinical impact is not too harmful, some anecdotal evidence is all we may have. For example, to increase breast milk supply, many women of Chinese descent refer to the magical powers of fish soup or green papayas. These are traditions passed down from generations — without studies," explains OB-GYN and Modern Fertility medical advisor Dr. Eva Luo, MD, MBA. "But, since consuming fish soup or green papayas are unlikely to harm a patient, this anecdotal evidence is okay. No one has ever conducted a randomized controlled trial (RTC) on fish soup/green papayas and breastfeeding, so who am I to say that the anecdotal evidence is of little value?"

Since placenta encapsulation is the form of placenta ingestion most often used, it's also what we have the most info on. Below, we're going deeper into what we know and don't know about placenta encapsulation so you have the info you need to make the right decision for you.

Placentophagy 101: How and why do people eat their placentas?

Consuming the placenta after birth is also known as "placentophagy," and it’s prepared to be consumed raw, cooked, frozen, in a tincture, dried, or encapsulated (the latter is the most common).

One 2013 survey found that the prevention and improvement of postpartum depression and mood disorders was the most common reason for taking part in a course of placenta capsule treatment. Advocates also say that ingesting your placenta post-birth can boost energy levels and the immune system, “balance” hormones, and improve postpartum recovery and lactation, among other benefits.

According to the Association of Placenta Preparation Arts (APPA), an online, comprehensive certification program for specialists in placenta encapsulation:

“Each placenta is different and each person has different needs, therefore the benefits are likely to be different for each individual person. We have heard everything, from increased energy and milk supply to radiant skin and hair. The important thing to remember is that the placenta is not a highly regulated drug — it is nutrition. Like most things you ingest, there are chemical compounds, minerals, vitamins, and even hormones that will have an effect on your body.”

Has eating the placenta always been a thing?

Nearly all mammals who develop placentas during pregnancy, including non-human primates, eat their placentas after birth — humans are the only ones who don't on the same scale of frequency. (Researchers are trying to understand why.) Even though the practice isn't as widely adopted among humans as it is among our mammalian counterparts, the concept of eating your placenta for health benefits was documented in the US as early as 1902 and gained momentum in the US in the 1970s.

One possible reason eating placenta isn't more popular today might be due to questions of its safety. In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a statement advising that placenta encapsulation in particular should be avoided because the placenta encapsulation process doesn't eradicate infectious pathogens. (Though the steaming process is intended to remove bacteria and viruses, because the practice of placenta encapsulation isn't regulated, heating standards may vary across training organizations.) This statement came after a baby was diagnosed with group B Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS), which they then identified in the breastfeeding/chestfeeding parent’s placenta capsules (though not in the milk).

It’s the absence of guidelines mentioned above that led to the formation of APPA. When completed appropriately, “both steam-dehydrated ... and raw-dehydrated preparation methods exceed the death point for GBS,” explains APPA. That’s why they suggest only using “properly trained encapsulation specialists” who are trained “not only in the physical encapsulation process, but in bloodborne pathogens and food safety” to ensure the proper heat levels are reached.

On this point, Dr. Luo has some words of advice: "If encapsulation is pursued, I strongly recommend inquiring about how the placenta is prepared and ensuring that the service and facility has passed necessary sanitation standards to reduce the risk of infection," she says.

Placentophagy in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)

APPA explains that placenta has been used by practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for centuries. Here’s why: “People are depleted of qi following birth because they give off their own life essence in bringing a child into the world … We have found historical evidence for use in treating insufficient lactation by boosting qi (energy or warmth) and nourishing the blood. Zǐ hé chē, or placenta, is said to be effective through the lung, liver, kidney, and heart channels of the body.”

If you're interested in ingesting your placenta, there are a few ways to do it

1. Placenta encapsulation: The most common way to ingest a placenta is in capsule form. The placenta encapsulation process typically starts within 24 hours of birth:

First, the placenta is normally steamed (to remove potential bacteria and viruses) and then dried in a professional food dehydrator before being ground into a powder.

It’s then packed into capsule shells.

Sometimes the placenta is processed into a capsule format "raw" by skipping the steaming step.

2. Preparing the placenta to be consumed on its own: When preparing a placenta to be eaten, it’s steamed, cooked, roasted, or baked, and then consumed by itself — or as a substitute for animal meat in dishes. These are the two main types of placenta preparation processes:

The TCM process: Inspired by the traditional placenta cleaning and preparation method that dates back to ancient Chinese cultures, this process uses gentle steaming with herbs and spices (most commonly lemon, ginger and chilli) before being put through a food grade dehydrator. This shrinks the placenta and results in fewer capsues than other methods.

The raw process: The raw process follows the same steps as the TCM process but skips the steaming step before dehydration.

3. Other methods of eating the placenta: The placenta is also sometimes processed into extracts, or distilled as tincture to be sprinkled or blended into liquids, instead of capsules. Less commonly, it can be frozen for use in smoothies.

What does the research say about placenta encapsulation?

Most of the research we have around ingesting the placenta centers on placenta encapsulation — not eating your placenta right after birth like many other mammals do. And most of the evidence you'll find of health benefits for both the birthing parent and the infant come from anecdotal reports. With those caveats in mind, keep reading for what we do know about placental ingestion and positive outcomes.

Nutrients and hormones can be found in placenta after it's processed for encapsulation — but we're still discovering how beneficial that might be

Research shows that the levels of some important nutrients and hormones can make it through the processing needed for placenta encapsulation. What's not yet demonstrated, though, is exactly how helpful that might be:

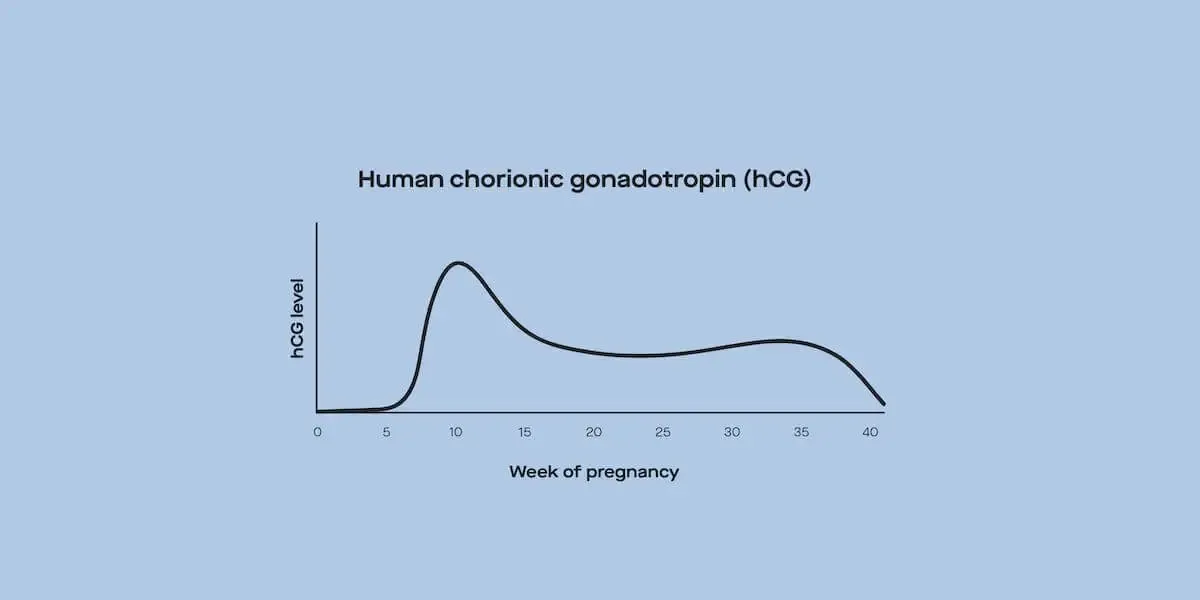

In one 2016 study, researchers analyzed 28 placentas to see if the concentrations of 17 hormones — including estrogens and allopregnanolone, the latter of which is used in a synthetic form in the only FDA-approved treatment of postpartum mood disorders — could withstand the encapsulation process. They identified detectable levels of 16 of the hormones post-capsulation, some with levels high enough to potentially lead to health benefits.

A 2018 review seconded the above study's findings, but added that the bioavailability of ingesting the hormones by mouth (i.e., how easy it is for the body to use them) isn't totally clear. Still, the researchers concluded that even a placebo effect of benefits could ultimately be helpful in the absence of any risks.

Several studies (like here and here) have looked at the amount of nutrients found in placenta after it's been processed for encapsulation. Placenta encapsulation likely maintains some of the nutritional content through processing, but just like any over-the-counter supplement, the levels on their own might not meet recommended daily amounts of nutrients.

There’s some evidence of postpartum benefits, but the research is mixed

The best evidence we have so far found little-to-no benefits for postpartum mood or other effects of low-hormone-dosing with capsules over the postpartum period:

In a controlled study of 28 women who consumed their placentas (27 via encapsulation), no significant differences in depression symptoms, energy levels, or plasma vitamin B12 levels were found. This is the largest study to date that examined the effect of postpartum placenta consumption on mood and energy using objective measures.

The above findings echo other research into placentophagy too, like a 2018 study into mood, bonding, and fatigue after placenta ingestion.

Some studies have looked at whether or not the hormones present in placenta can help with postpartum mental health. One of these studies (a very small one) measured salivary hormones after placenta ingestion and found no significant difference in hormone levels post-ingestion, compared to placebo groups. The researchers summarized their learnings by explaining that while placenta capsules may have a small effect on hormones, we don't yet know the full impact of this on mental health.

There's little reason to believe that placenta encapsulation could be harmful

Despite the recommendation from the CDC citing the risk of pathogen transmission from the birthing parent to the infant via placenta ingestion, one of the reviews we mentioned earlier tells a different story: The researchers pointed out that, in the documented incident of group B strep infection in an infant whose birthing parent was taking placenta pills, stomach acid would have most likely destroyed pathogens during the digestion process. This means that the route to infection was likely something other than breast/chest milk affected by placenta encapsulation.

Other purported risks may also be exaggerated:

Some blogs cite the accumulation of heavy metals as a major issue with placenta encapsulation, but the most recent studies in this area found negligible levels of heavy metals.

There have also been claims of adverse hormonal effects, from decreased milk supply (which is also, interestingly, a suggested benefit) to blood clots to breast/chest budding and vaginal bleeding in the infant — but other studies (like this one) have demonstrated that the hormone levels in dehydrated and cooked placenta (though not raw) are very low.

All of this said, certain medications taken during labor may accumulate in the placenta — in some cases leading to your healthcare provider suggesting you avoid eating your placenta. The review's authors also write that risks of accumulation of toxins in the placenta are higher for smokers (though most studies have excluded smokers).

Finally, your feelings going in can have a big impact on your feelings after

Researchers have found more positive attitudes toward placenta encapsulation among those who’d opted for home births. And after collecting data from online birthing forums, another study suggested that those who value personal accounts of birth and postpartum care over medical research on these subjects could be more likely to engage positively with placenta encapsulation and perceive positive outcomes from it.

Interested in placenta encapsulation? Here are some other considerations

Situations in which placenta encapsulation isn’t recommended by specialists: According to APPA, these include:

Chorioamnionitis (infection of the membranes), Lyme disease, or Clostridium Difficile (C. Diff)

Infection during or immediately following labor and delivery or other active infections that may be reacquired

Neonatal infection within the first 48 hours postpartum

Improper storage or refrigeration of the placenta

The cost of placenta encapsulation: The cost of placenta encapsulation is typically between $125 and $425). The price can sometimes climb above $425 depending on the type of placenta preparation opted for, and the type of herbs and spices that are used in the steaming process.

Using an encapsulation service or doing it yourself: Some people choose to encapsulate their placentas post-birth using a DIY route), which follows the same chosen method (typically TCM or raw), but the responsibility of purchasing all the equipment involved (e.g., a food dehydrator, capsule shells, an encapsulation machine, airtight storage jars, rubber gloves) and carrying out each stage of processing and encapsulating lies with them. (Reminder that APPA recommends working with a specialist.)

Hospital policies around taking your placenta home: APPA explains that three states (Hawaii, Oregon, and Texas) have established laws that protect the right to take home your placenta, but that there aren't any states with laws against it. However, some hospitals might have policies in place that make that difficult because "the placenta is treated as medical waste and disposed of along with other biohazard waste in the hospital," says Dr. Luo. An exception would be if the placenta was needed for further evaluation of an infection or complication since it's "often a proxy for the pregnancy environment in research." If the placenta is inspected, this could delay your ability to take it home or prevent it entirely — after that, though, the placenta may no longer be intact. APPA adds that this can be avoided by taking a culture or a smaller portion for testing and preserving the rest for the patient.

The bottom line

While there isn't tons of clinical evidence supporting the health claims behind placenta encapsulation, the anecdotal evidence shouldn’t be discounted — and the risk of contamination or toxicity from ingesting the placenta has been proven to most likely be low, despite official guidelines. The decision really comes down to how you and your provider feel about it.

If eating your placenta is of interest to you, talk to your healthcare provider. As with all things relating to your health and the health of your future child, your doctor is always your best resource. As Dr. Luo neatly sums it up: "The role of a clinician is to help patients sift through the available evidence to make the best decision for them."

This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Eva Marie Luo, MD, MBA, OB-GYN at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Clinical Lead for Value at the Center for Healthcare Delivery Science at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.