Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Many of us have heard about the role of age (including the age of our ovaries) in reproduction and fertility. But there are other factors, also outside of our control, that can impact reproduction.

Below, we’ll discuss how racial and ethnic factors may contribute to differences in reproduction and reproductive care — from an increase in certain medical conditions that impact fertility to differences in the ability to access care.

The relationship between race and reproductive outcomes

First, what do we mean when we’re talking about race and ethnicity?

Race is associated with our biology and is linked to physical characteristics such as skin color

Ethnicity is based on our cultural expression

Both race and/or ethnicity can contribute to our healthcare experience and outcomes — not just because of our biology alone, but also a complicated mix of "weathering" (repeated exposure to stressors), medical bias in healthcare, and systemic racism.

In this section, we’ll break down what the research says about the prevalence of health conditions and reproductive outcomes in different racial groups. One caveat to note is that the discussion and data presented below are based on a sample size of the population. Just because we say that a certain racial group may have a higher incidence of a condition does not mean you’ll automatically have this condition or disease if you are of that race.

Black people with ovaries are 2x as likely to experience infertility

Overall, infertility impacts approximately 12% of couples in the US. In healthcare, infertility is defined as the inability to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months of appropriately timed intercourse (around the “fertile window”). Female age plays a major role in the ability to successfully get pregnant — but race may also play a role.

A 2014 national survey reported that Black people with ovaries were almost twice as likely to experience infertility as those who were white, but half as likely to seek out care. A more recent study found relatively equal rates of infertility among different races, but still note that Black and Mexican-American respondents sought out care for infertility significantly less often than Asian and white respondents did.

Black and Hispanic people have a harder time accessing fertility care

Studies have consistently demonstrated that minority races, in particular Black and Hispanic individuals, have more barriers to accessing fertility care than those who are white.

One survey of 743 women seeking treatment for infertility noted that:

Black and Hispanic women were significantly more likely to report difficulties finding a doctor they could trust and afford treatment from.

Black and Chinese-American women were significantly more likely to report social stigma as a barrier to seeking infertility care.

In another survey study of 1,460 women presenting for infertility care in a state that mandates insurance coverage of IVF:

Black women were almost 3x as likely to report their race as a barrier to seeking infertility care compared to Hispanic and Asian women.

Black and Hispanic women reported traveling twice as far to seek care than white and Asian survey respondents.

Black and Asian people have lower IVF success rates

In-vitro fertilization (IVF) is a procedure whereby the ovaries are stimulated to grow multiple follicles and subsequently retrieved, followed by fertilization of those eggs with sperm in the embryology lab. The resulting embryos then develop in the lab and are transferred back into the uterus, either during the same cycle as the egg retrieval or in a frozen embryo transfer cycle.

Several studies have shown racial disparities in IVF outcomes among Black women and Asian women, who have significantly lower success rates from IVF compared to white women:

One study that assessed women presenting for fresh IVF transfer between 2010-2012 assessed and compared pregnancy and live birth rates according to race (white, Black, Asian, Hispanic) and noted significantly lower live birth rates in Black, Asian, and Hispanic women compared to white women (16.9%, 24%, 28.5% vs. 30.7%, respectively).

Black women were noted to have a

Other studies haven’t shown the same statistical discrepancy — what that means is that in some of these studies, there could have been other factors related to socioeconomic level and access to care that impacted the participants and their outcomes.

Research has also shown that Asian women require higher doses of IVF stimulation medications and have higher estrogen levels at time of transfer. (It’s been hypothesized that higher estrogen levels at time of transfer, within a fresh cycle, may adversely affect embryo transfer outcomes.)

There isn’t much data regarding Hispanic women and IVF outcomes. According to a review published in 2016, Hispanics made up 12.5% of the population but less than 6% of IVF data. More studies are needed to determine whether Hispanic ethnicity may also play a role in IVF outcomes.

Black people have slightly higher rates of miscarriage at 10-20 weeks

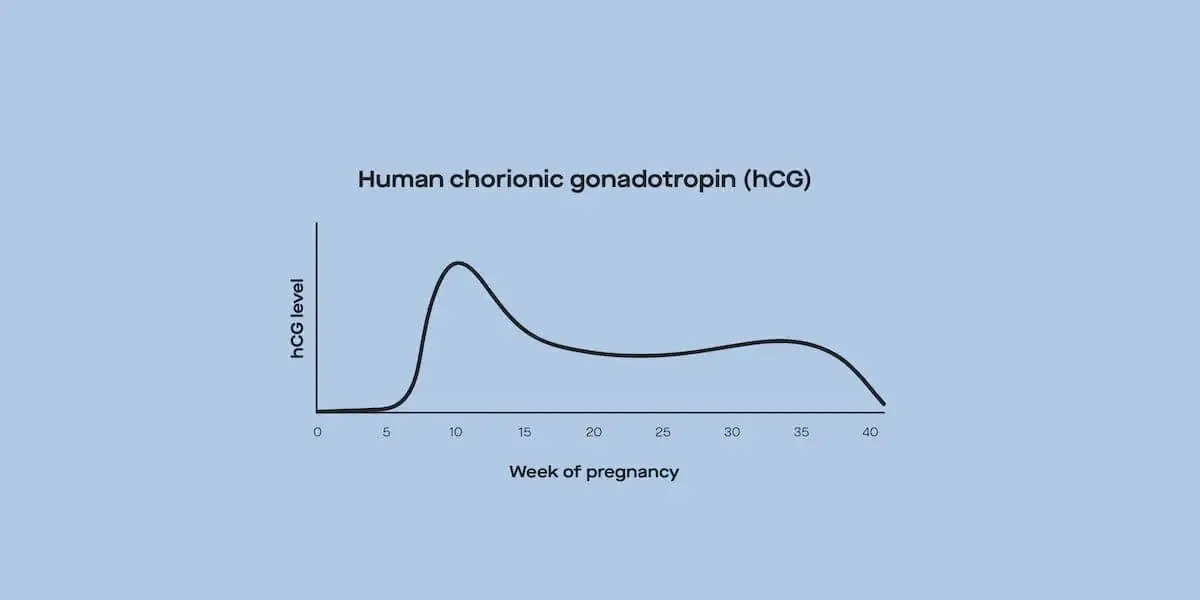

A miscarriage is defined as pregnancy loss occurring before 20 weeks gestation — and it has been reported that approximately 10%-15% of all clinically recognized pregnancies (those visualized on ultrasound) will end in miscarriage.

Studies focusing on race have been limited given the lower rates of minority women enrolled as participants, but one study of over 4,000 women (23% who identified as Black) noted a slightly higher miscarriage rate between 10-20 weeks gestation in Black women compared to white women. Prior to 10 weeks gestation, though, there was no racial difference in miscarriage. The mechanism behind the increase is not well understood, but may be related to differences in environmental exposures across populations or medical conditions that are more common in one group versus another.

Race and reproductive health conditions

The following conditions are more commonly diagnosed and reported among certain populations.

Black people with uteruses are 2-3x more likely to have uterine fibroids

Uterine fibroids are smooth muscle tumors (most often non-cancerous) that can develop within the uterus. Fibroids impact up to 70% of people with uteruses, and depending on the location of the fibroids within the uterus, can have varying effects on reproduction.

Before we delve into the topic of uterine fibroids, it’s important to know the three different types:

Subserosal fibroids grow on the outside of the uterus.

Intramural fibroids grow within the myometrium (or muscle layer of the uterus).

Submucosal fibroids grow within the endometrial cavity (where an embryo would implant).

In general, while fibroids have not been shown to directly cause infertility, they may be associated with distorted pelvic anatomy or altered pelvic blood flow, which could have an impact on reproduction. Removal of submucosal fibroids, in particular, may improve clinical pregnancy rates.

Race does appear to be a risk factor for developing fibroids as Black women are 2-3x as likely to be diagnosed with uterine fibroids compared to white women. They’re also more likely to have fibroids present at a younger age, have larger fibroids, and a higher number of fibroids within the uterus. An exact cause of this racial discrepancy is unknown, but may be related to differences in genetics, diet, psychosocial stress, and/or environmental exposures.

White and Asian people are more likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis

Endometriosis is a condition defined as the presence of endometrial (uterine) glands and stroma present outside of their normal location in the uterus. Risk factors include smoking, alcohol use, and lower body-fat percentage, but race may also factor into a person’s susceptibility to endometriosis.

A study of over 1,700 women with laparoscopy-confirmed endometriosis demonstrated white and Asian women had higher rates of endometriosis than Black and Hispanic women. While reasons for this remain unclear, one possible theory is that Black people may be less likely to access care for pelvic pain and more likely to be misdiagnosed with a different medical disease (like pelvic inflammatory disease).

Racial and ethnic differences may impact how PCOS presents

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine disorder impacting people with ovaries, affecting anywhere from 5%-15% of the population depending on the studies being assessed.

PCOS is usually accompanied by one or more of the following:

Irregular or anovulatory menstrual cycles

Elevated androgen levels or clinical evidence of elevated androgen levels

Polycystic ovary morphology (evidence of multiple immature ovarian follicles) on transvaginal ultrasound.

Because of these symptoms, PCOS can impact reproductive outcomes by potentially making it more difficult to conceive in those who don’t ovulate regularly or in those who never ovulate.

Overall, there does not appear to be a major difference in the prevalence of PCOS between different racial groups as the global prevalence of PCOS remains consistent based on studies in people from the US, UK, Greece, and Mexico. However, racial and ethnic differences may contribute to how PCOS presents and also what other metabolic conditions (such as high cholesterol and diabetes) an individual may be more likely to have.

Black people are diagnosed with STIs at higher rates

If left untreated, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), specifically chlamydia and gonorrhea, can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and impact fertility by causing tubal scarring and/or mucus adhesions within the fallopian tubes. Issues with the fallopian tubes are the cause for infertility in up to 35%-40% of couples trying to conceive. That’s because the fallopian tubes are critical to natural reproduction — they’re responsible for picking up the egg that was ovulated from the ovary, and where sperm and egg meet and fertilization occurs.

Additionally, early embryo development occurs in the fallopian tubes prior to the embryo entering the uterus and implanting. Damage in this area can impede the ability of the tubes to pick up the eggs and/or block sperm from meeting the egg. (Along with STIs and PID, prior ectopic pregnancy, ruptured appendix, and endometriosis may all increase the risk of fallopian tube damage.)

When it comes to being diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea, Black people with ovaries have up to a

Hypertension, diabetes, and Hashimoto’s are more common in certain populations

Chronic medical conditions (such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyper or hypothyroid disease) can all increase the risk of difficulty when trying to conceive or during pregnancy. Certain racial groups do appear to have higher risks of being predisposed to some of these conditions:

Black people with ovaries in the US are more likely to have hypertension as compared to white people.

Indigenous Americans, Alaskan Natives, and Black and Hispanic adults have higher rates of diabetes compared to white adults.

White people with ovaries are at a higher rate of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an autoimmune thyroid condition that can also impact reproduction.

Uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, and thyroid disease can all lead to a higher risk of difficulty conceiving and pregnancy complications. Thus, preconception care and early, adequate prenatal care are key to making sure these medical conditions are under control prior to trying to conceive.

Black and Hispanic people are more likely to have a higher body-fat percentage

The relationship between weight and fertility is a sensitive and complicated one. And while people of all sizes and weights go on to have healthy pregnancies, there is evidence that body-fat percentage can impact the chances of certain health conditions, as well as both fertility and pregnancy outcomes.

First, it’s important to note that most studies use body mass index, or BMI, as a stand-in for body-fat percentage and a way to assess the likelihood of associated health risks. While calculating BMI can be quite simple using a BMI calculator, the tool isn’t very good at determining the type of body mass (fat or muscle) or distribution of body fat (fat that is preferentially distributed in our midsection, known as visceral fat) — the latter of which is shown to contribute to higher rates of diabetes and heart disease, to name a few. Additionally, the original data BMI charts are based on primarily used white Europeans with sperm.

Like we mentioned earlier, it’s absolutely possible to conceive without intervention if you have a higher body-fat percentage. That said, a higher BMI has been linked to irregular menstrual cycles — which could make it more difficult to get pregnant. It’s also been linked to reduced live birth rates during fresh IVF cycles.

According to the latest Centers for Disease Control (CDC) statistics from 2018, approximately 42.4% of US adults have a BMI >30 (classified as “obese,” or a higher body-fat percentage). Black and Hispanic people had the highest age-adjusted rates of BMIs >30 at 49.6% and 44.8% within the US, and non-Hispanic Asians had the lowest rates.

Now that we have this information, what can we do?

While the reasons for all of the above statistics are complex and many are beyond our control, awareness of these risks — either due to family history, genetics, and/or race — and how those medical conditions may impact future reproductive and overall health is key. What is in our control, however, is gathering as much reliable medical information as we can about what we might be predisposed to.

On the provider side, training around cultural competence and unconscious bias is crucial. And on the patient side, taking the time to find a doctor you feel comfortable with is incredibly important.

Before each appointment, I recommend writing down any symptoms you’re experiencing (as well as the degree of pain you’re feeling) and any questions or concerns you have to ensure you’re getting the most out of your time. You may also consider bringing a friend or family member to an appointment (post-COVID) or joining you on a telemedicine video call — that way, you have another set of ears.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.