Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Growing up, we all watched the standard puberty video: You know, that video that told us a whole lot of nothing — conversely leaving us with a whole lot of questions? How many times have you glanced down there just out of curiosity? It may be time to grab a mirror and catch up with what’s actually going on with your vagina.

Vulvovaginal anatomy and how it all actually works

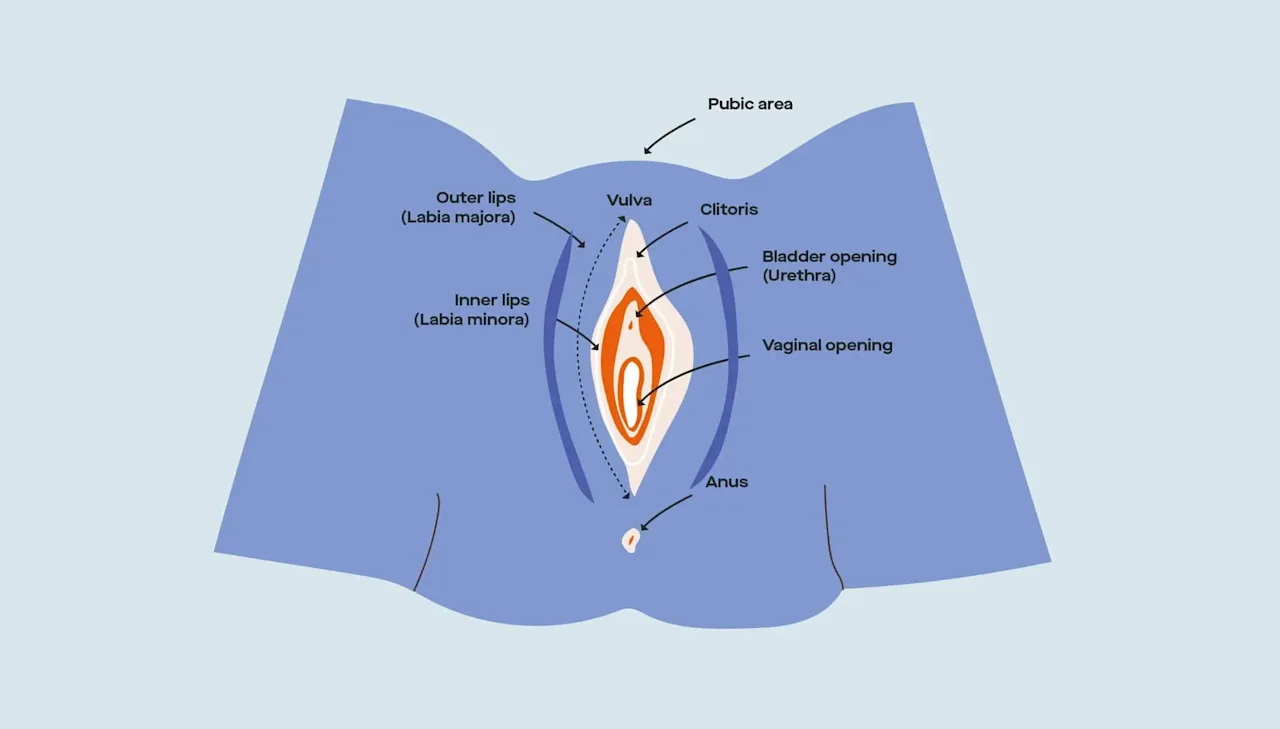

First things first, the proper term for what you may call your vagina is really your vulva. The vulva is the exterior part of your genital anatomy whereas your vagina is the tube that connects your vulva and your cervix — or the “neck of the uterus” as Doula and birth educator, Amy Lewis, says. Be aware that no two vulvas look the same. That said, listed below are the anatomical parts of your vulva and vagina that you can familiarize yourself with to help you identify what exactly your normal is.

Vulvas typically include:

A set of anatomical body parts: the labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, clitoral hood, and opening to the vagina (vestibule)

Bacterial colonies that make up your vaginal microbiome

Vaginas include:

A combination of smooth muscle and ridges, known as rugae

Secretion of certain fluids: Cervical mucus and other vaginal discharge

Vulvovaginal anatomy (external)

Starting from the outside of your body, where the vulva is…

Mons pubis. That area right above your vulva where you get pubic hair during puberty.

Labia minora/labia majora. The inner (minora) and outer (majora) lips that wrap around your vaginal opening.

Clitoris. Sometimes known as the clit, where the lips of your labia minora meet at the top. In other words, the tip of the iceberg. Oftentimes, you cannot see the clitoral gland without pushing back the overlying tissue called the “clitoral hood.” Note: Both your inner and outer labia, as well as your clitoris, swell or engorge when you’re aroused.

Urethra opening. Located a little below your clitoris, this is the hole that you pee out of.

Vaginal opening. Where menstrual blood leaves your body, where babies come out of (sometimes — C-sections happen ~32% of the time), and where sex toys, penises, and fingers can potentially go inside.

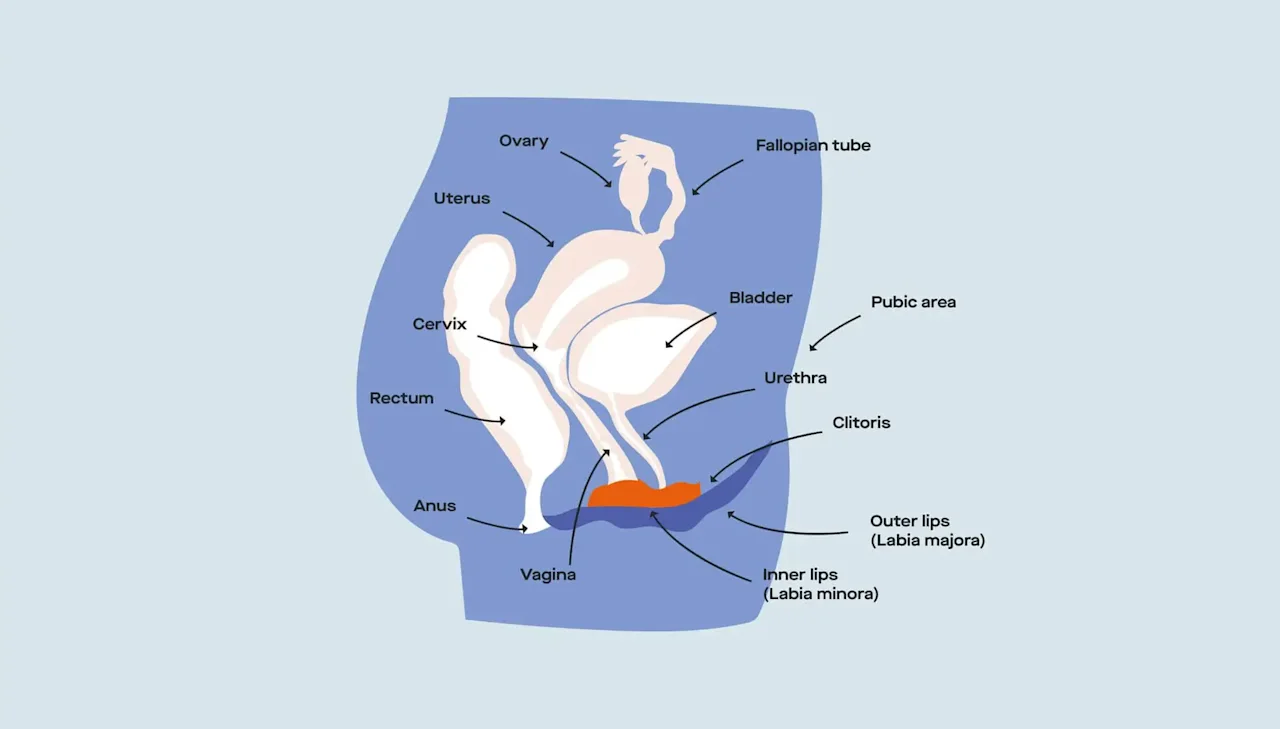

Vagina. Your vagina is a tube that connects your vulva to your cervix.

Pelvic floor. A set of muscles that wrap around the vagina, urethra, and rectum, and provides support for your organs, helps you with continence (control of urination and bowel movements), and aids in orgasmic pleasure.

Once you travel through the vagina, you then get to the internal parts of your reproductive system like the cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.

Vulvovaginal anatomy (internal)

How to keep your vulvovaginal area healthy (and happy)

Dr. Jennifer Conti, OB-GYN and medical advisor to Modern Fertility, says “a healthy vulva is one that looks and feels like your own personal baseline and without itching, lesions, or foul-smelling discharge.”

In her book, The Vagina Book: an owner’s manual for taking care of your down there, Dr. Conti outlines the three Ds of caring for your vagina: Douching (don’t!), discharge, and “does it look normal?” (Keep reading as we dive into each of these major points!)In our research, we learned that the vagina sheds every four hours during a person’s reproductive years. According to Dr. Jen Gunter’s The Vagina Bible, the dead cells not only feed healthy vaginal bacteria but also act as a decoy for unhealthy bacteria trying to enter your system. (So, yes — the idea that your vagina is a “self-cleaning oven” is 100% true.)

So there isn’t a whole lot you have to do besides let your vulva do its thing. A few ways to do that include…

Promote a healthy environment. Your vagina and your vulva are extremely sensitive areas of your body. It’s important to create a healthy vulvovaginal environment to reduce the risk of vulvar irritation or bacterial infections. On the outside, Lewis recommends wearing undergarments that can breathe — like cotton! On the inside, Dr. Heather Jeffcoat, physical therapist and owner of Femina Physical Therapy, recommends drinking more water. “If your mouth feels dry, just imagine how your vagina feels!”

Embrace your scent. According to Dr. Conti, “Vulvas and vaginas are not supposed to smell like fresh laundry or spring daisies. It does not need any chemicals, soaps, detergents, wipes, or fresheners to keep it clean.” Bottom line? Your vagina has its own smell and the sooner you recognize and embrace yours, the easier it’ll be for you to notice if something is seriously off.

Pay attention to discharge. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the vagina begins to produce discharge at puberty. "Normal" discharge is clear to white and doesn’t have a noticeable odor because it's mostly made up of water and contains microorganisms that keep your genitals clean and healthy (by removing dead cells from the lining of the vagina!). Your discharge changes throughout the menstrual cycle and can tell you a lot about the stage of the cycle you're in. Monitoring discharge like cervical mucus can even help you understand whether or not you're approaching ovulation.

Listen to your body. If having sex without a condom makes your vulva itchy or raw or you see your vulva breaking out with bumps after sex with a condom, your body is trying to tell you that something is messing with its natural balance. The vulva comes with its own array of skin conditions as well as interior infections. Keep an eye on what’s typical for your body and what that means for your health.

Your vagina has a specific pH — and it likes it that way

Dr. Jen Gunter, OB-GYN and author of The Vagina Bible, says that a person with a vagina has a typical pH between 3.5-4.5 and that pH is the byproduct of the lactic acid that our lactobacilli bacteria produces.

Just like your vulva is unlike any other vulva, your vaginal pH is also specific to you. Your vaginal pH can shift during menstruation, illness, sexual arousal, and pregnancy.

Because the vagina is naturally acidic, any shift toward becoming basic can indicate vaginal infection. But this imbalance has nothing to do with you not keeping your “vagina acidic enough through proper cleaning,” says Dr. Conti. “The vaginal hygiene industry obsesses over vaginal pH, but the truth is, the only condition we ever test vaginal pH for is bacterial vaginosis (BV).”

That’s the vaginal infection that shows up sometimes when there’s a shift in your vaginal microbiome, with its gray discharge and fishy odor. (We’ll cover the impact of BV a little later.)

What’s the deal with probiotics for vulvovaginal health?

A 2020 Microbial Cell study says we have many microbes living in our bodies; the two predominantly found in the vaginal area are candida and lactobacillus. Lactobacillus is a probiotic, a good bacteria that can also be found in your gut.

According to ACOG, estrogen in the body helps keep the “vaginal lining thick and supple and encourages the growth of lactobacilli.” It’s these bacteria that “make a substance that keeps the vagina slightly acidic.” The acidic nature of the vagina is what protects it from harmful microorganisms like candida, a fungal bacteria that causes yeast infections.

Despite the link between where lactobacillus is found (the gut and the vulvovaginal area), the science community has only recently begun exploring this connection with a new focus on finding a way to “restore the balance of vagina microflora” instead of modifying what’s inside. This is where probiotics come in — the use of them (mainly the lactobacillus family) to combat disease-causing bacteria. (Some probiotics with lactobacillus claim to promote both gut and vaginal health.)

There still isn’t enough research or evidence to show how and to what extent probiotic supplements definitively influence vulvar health. We’ll save a deep dive on this for a future article.

What issues can spring up from ignoring vulvovaginal health?

Taking care of your vulvovaginal health is an important step in taking care of your overall wellbeing. When you practice more don’ts than dos, you can experience imbalances in your vaginal ecosystem.

A few ways your vulvovaginal health can impact you if you ignore it:

Sexual dysfunction. One in every three people with vulvovaginal areas experience some form of sexual dysfunction. According to Dr. Jeffcoat, the pain you experience during sex can be a result of how much water you drink in a day or how often you perform kegels. Note: there are many other conditions that can contribute to pain with sex, or dyspareunia. While kegels are good for incontinence, Dr. Jeffcoat also recommends doing kegels to “learn to let go and lengthen” your pelvic floor muscles. Hyperactive pelvic floor muscles and vaginal dryness can make sex painful and less enjoyable.

STIs. The CDC says there are 20 million new STI cases every year in the US alone. Anytime you have unprotected sex, there's a risk of experiencing STIs including high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV), chlamydia, and gonorrhea, which can impact fertility if they go untreated.

Vaginal infections. The two most common infections that appear due to an imbalance in your vaginal ecosystem are bacterial vaginosis (BV), affecting 15-50% of all people with vulvovaginal areas, and yeast infections, affecting over one million people every year.

Anxiety. Recent studies suggest a possible connection between your vaginal health and your psychological well-being. One study found that people with recurrent vaginal infections had lower rates of sexual satisfaction and orgasm, and higher rates of depression and anxiety, but it’s difficult to say if one issue is necessarily caused by the other. The most honest way to handle vaginal issues is to face them head on. Make a note of what your vagina typically feels, looks, and smells like and to see a doctor if anything changes.

The link between vaginal health and fertility

There are a few vaginal issues that can impact fertility, including bacterial vaginosis (BV) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

The American Pregnancy Association says that BV is three times more prominent in people with infertility compared to people who don’t have infertility issues. BV is also responsible for added risks during a pregnancy including miscarriages, preterm births, and postpartum infections.

STIs like chlamydia and gonorrhea, if left untreated, have the ability to influence fertility by causing and then spreading pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) into the fallopian tubes. PID can be painful and result in issues getting pregnant.

Something else we found during our research is the existence of a supposed combined microbiome that shows up during sex: the seminovaginal microbiome. This microbiome may be able to affect fertility in opposite-sex couples trying to conceive. But since this study and other research on microbiotic health are still new, we can’t say for sure how this microbiome they found influences reproductive outcomes.

How vaginal health promotes overall health

Your vaginal health impacts your overall health, and vice versa. Listening to your body and paying attention to its typical behaviors can help you suss out any and all experiences that are out of the ordinary for you — like a dry vagina, or painful sex.

Taking care of your vaginal health also takes care of your mental and emotional health. Feeling confident and comfortable in your skin leaves you with less room for anxiety and worry.

There’s a huge need for more research on how vulvovaginal health influences fertility and reproductive health. Consider this as a starting point for continued learning about the ins and outs of the vulva and vagina — and don’t throw out your handheld mirror just yet! Remember that the more you learn, the more intimate you’ll become with your body.

This article was reviewed by Dr. Jennifer Conti, MD, MS, MSc. Dr. Conti is an OB-GYN and serves as an adjunct clinical assistant professor at Stanford University School of Medicine.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.