Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

As you likely already know, smoking cigarettes (aka tobacco) during pregnancy is a big “no-no.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises that pregnant and breastfeeding/chestfeeding people avoid smoking marijuana too. But what if we’re not thinking about getting pregnant for a while? Could enjoying marijuana now negatively impact our ability to conceive later? If marijuana use is legal, does that mean it’s safe before and during pregnancy?

Honestly, we don't totally know yet because we haven't completed as many studies as we need. That's a pretty confusing answer, right? Unfortunately, science doesn’t always have the conclusive answers we crave — but given what the medical community does know, for the time being, choosing not to smoke weed if you're trying to get pregnant is the safest approach to avoid possible health effects on conception and the fetus down the line. Experts also recommend always talking to your healthcare provider about the potential impact of your cannabis use.

We dug into the research to understand exactly where we need more data around this sometimes medicinal and sometimes recreational drug as it relates to fertility and reproductive health.

Here are the biggest takeaways

Tetrahydrocannabinol, aka THC (the active ingredient in marijuana), may affect hormone levels and interrupt your menstrual cycles.

Studies on time to pregnancy among cannabis users have mixed findings.

Research on the impact of marijuana on infertility treatment is ongoing, but it may play a role in early pregnancy loss after in vitro fertilization (IVF).

While the effects of marijuana use on fetal development are not yet fully understood, cannabis use during pregnancy may be associated with adverse birth outcomes.

There's scientific evidence possibly linking weed use in people with sperm to lower sperm counts, reduction in sperm concentration, higher rates of abnormal morphology (shape) and reduced motility (movement), as well as lowered luteinizing hormone (LH) levels.

Ultimately, the research around marijuana and fertility isn't conclusive — but ACOG still

What does the science tell us about marijuana and fertility?

The simple summary is that there’s a lot we still don’t know about marijuana and reproductive health. Ethical limitations prevent thorough studies (read: experimental, where factors are introduced by researchers) into how cannabis impacts fertility and fetal development, so right now, the science is largely based on observational studies (examination of real-world outcomes, without researcher involvement) of cannabis users. That means we don't have the most conclusive results. Some studies show effects from marijuana use on male and female fertility; other studies don’t.

As one 2020 study of marijuana and female fertility explains, “Studies are limited in number, with small sample sizes, and are hampered by methodological challenges related to confounding and other potential biases. There remain critical gaps in the literature about the potential risks of cannabis use.”

Research into marijuana’s impact on people of reproductive age is ongoing, so it’s important to stay up to date and seek guidance from your provider. For now, let’s explore what we do know about cannabis and reproductive health.

A quick explainer on marijuana and the reproductive system

Your body actually has a system that mediates the effects of cannabinoids (the substance group in marijuana) when they enter your bloodstream and helps your reproductive system function: the endocannabinoid system (ECS). Specifically, the ECS plays an important role in implantation and pregnancy maintenance. Because of this connection, researchers need to continue studying how reproductive function is impacted when the ECS and its receptors are activated by cannabis in the bloodstream, especially since results are mixed in terms of potential complications like reduced fertility and pregnancy loss.

The authors of studies researching cannabis and fertility agree that there’s much more work to be done, plus a need for additional studies on humans — not only our furry friends — to fully understand the topic.

Marijuana and the menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle has a lot to do with fertility. In order to naturally conceive, the ovaries must release an egg (aka ovulation) for a sperm to fertilize it. According to the studies linked above, there's a potential association between marijuana and anovulation (the complete absence of ovulation).

Anovulation and occasional use: “Women who use marijuana have a slightly elevated rate of menstrual cycles that lack ovulation,” write one 2016 report's authors. “One study found an association between occasional marijuana use (self-reported 1-3 times in the three months preceding the study) and prolonged follicular phase (3.5 days), resulting in delayed ovulation.” The follicular phase of the menstrual cycle is when a few ovarian follicles — which house and release eggs — develop in preparation for ovulation. But only one of these follicles will release a fully matured egg. If the follicular phase is delayed, ovulation — which is key to conception — is thus also delayed.

Anovulation and moderate to heavy use: An often-cited 2007 study focusing on moderate-to-heavy marijuana users (at least three times per week over the six months preceding the study) found that individuals were more likely to experience menstrual cycles that were anovulatory. This study was particularly meaningful because it recreated the findings of a 1981 study using five rhesus monkeys.

What we still don’t know: As the 2016 report points out, these experiments were conducted with small sample sizes and did not take into account the exact dosage of marijuana or if other substances like alcohol or tobacco were used, which can also impact fertility. The authors write, “Therefore, the results of these studies should be interpreted with caution.”

Marijuana and fertility hormones

Let’s take things one step further: The menstrual cycle is regulated and fueled by hormones, like estrogen, progesterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH), to name a few. If marijuana impacts the menstrual cycle, that's probably the result of marijuana’s influence on fertility hormones. Here’s a recap of these hormones’ responsibilities in the phases of the menstrual cycle:

Follicular phase: LH and FSH stimulate the growth of several ovarian follicles, kicking things off. As the “dominant” follicle (the one that will release an egg) grows, estrogen rises to prep for ovulation and FSH levels begin to fall. This drop in FSH causes the other ovarian follicles (with the exception of the dominant one) to die off.

Ovulation: When estrogen levels peak, the body produces a surge of LH, which helps the egg reach final maturation and ultimately release from the follicle.

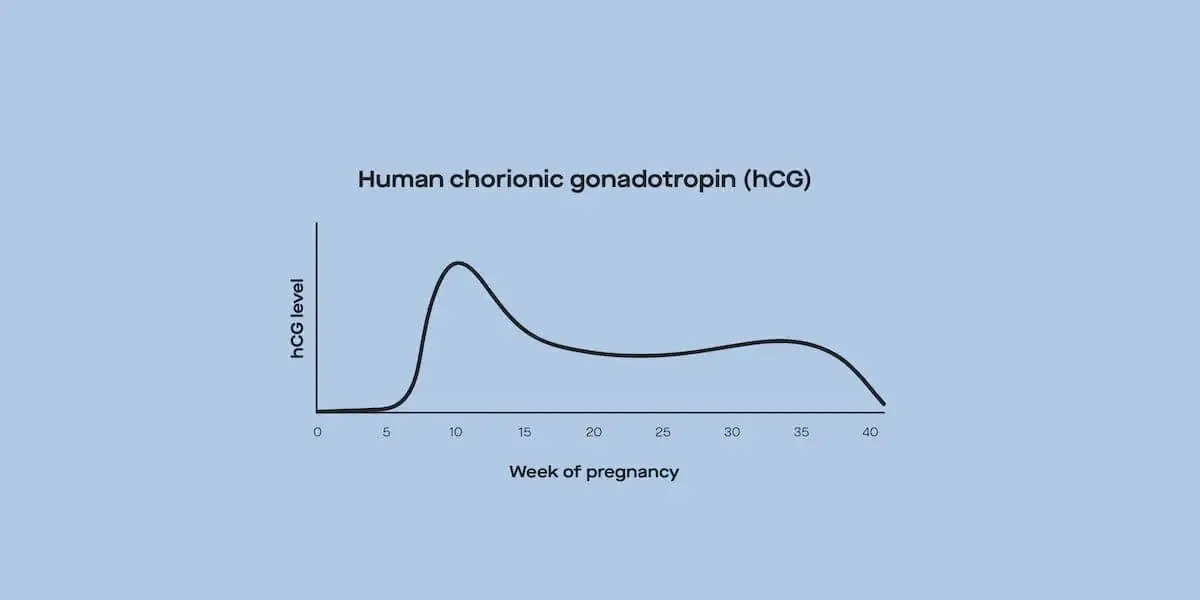

Luteal phase: The increase in LH cues the body to produce progesterone, which helps the lining of the uterus thicken in anticipation of a fertilized egg making its home there (it’s like making a comfier bed for the fetus). If sperm fertilizes the egg and pregnancy occurs, progesterone levels continue to rise. If fertilization doesn’t occur, progesterone levels drop.

Menstruation: If an ovulated egg isn't fertilized by sperm, the drop in progesterone causes the egg and the uterine “bed” to shed in the form of your period as the next follicular phase begins.

The point is: Reproductive hormones work together and take their cues from one another to make conception possible. Here’s one example from the 2016 report of how marijuana potentially impacts these hormones — particularly LH and FSH:

LH and FSH are types of “gonadotropins,” the categorical name for hormones released by the pituitary gland. The report says that THC can suppress the release of gonadotropins, including LH and FSH.

Studies included in the report show that inhaling one gram of marijuana is enough to suppress LH levels during the luteal, but not follicular, phase of the menstrual cycle.

The authors write, “Suppressing LH during the early luteal phase may terminate early pregnancies by reducing ovarian production of progesterone, a hormone that is necessary to maintain and support pregnancy.”

As a reminder, the luteal phase refers to post-ovulation, when the body is prepping for either pregnancy or menstruation — and a rise in LH is what cues the body to produce progesterone and create the uterine “bed” for the fetus.

Marijuana and time to pregnancy

Do changes in your reproductive hormone levels and menstrual cycles mean marijuana can potentially affect how long it takes you to conceive? Because studies are few and observational (meaning it's hard to isolate cause and effect), we don’t know much yet. Here’s what the research tells us so far:

A 2017 study found that women who reported smoking marijuana within the last year took slightly longer to conceive than participants who did not smoke weed. But before we can use this data to come to any conclusions about marijuana’s effects on time to pregnancy, we would need to know how much weed the subjects smoked and when in their fertility journeys they smoked it.

In comparison, two different studies from 2018 found little connection between the drug and time to pregnancy:

One study of people who used marijuana and did not have diagnosed infertility issues found little overall association between cannabis use and the ability to get pregnant.

Another 2018 study surveyed 1,000+ women who were trying to conceive from the National Survey of Family Growth to document time to pregnancy for both men and women. Rates for cannabis users and non-cannabis users revealed no notable differences, and authors concluded that this particular study suggested “neither marijuana use nor frequency of marijuana use” affected time to pregnancy.

Mixed results are currently the norm in marijuana and fertility research, which all points to the need for more studies.

Marijuana and assisted reproductive technology (ART)

Knowing what we do about cannabis and hormonal changes, how might using marijuana affect assisted reproductive technology (ART) and infertility treatment? Again, research is ongoing, but one 2019 study gives us some insight:

Researchers followed 421 women and 200 of their partners during in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments.

When 317 of these participants had positive pregnancy tests, nine of those women were cannabis users.

As their early pregnancies continued, the nine women who used cannabis were twice as likely to experience pregnancy loss, compared to the other 300+ non-cannabis users. Specifically, after 16 rounds of ART among the subjects, half of the cannabis users’ pregnancies were lost, while approximately one-quarter of the non-cannabis users’ pregnancies were lost.

Marijuana and pregnancy

Once pregnant, it's important to consider the effects of cannabis on both the pregnant person and the fetus. Let’s start with the basics: We know the ECS plays an important role in implantation and pregnancy maintenance — and research tells us that marijuana crosses the placenta and as well as passes into breast/chest milk. This means marijuana use has the ability to affect pregnancy outcomes like miscarriage and preterm birth and possibly impact fetal development.

What the science says about marijuana and fetal development

Here's what we have evidence for so far in terms of marijuana and pregnancy:

Fetal development:

Human fetuses exhibit cannabinoid receptors in the central nervous system as early as 14 weeks with increasing receptor density as the pregnancy progresses (demonstrated here and here). This suggests a role for endocannabinoids in normal human brain development.

Some human and animal studies show in-utero exposure to marijuana may lead to lower scores on visual problem-solving tests (shown here and here), behavioral problems, and decreased attention span.

Are these potential effects on fetal development impactful in the long run? Unclear. One longitudinal study (findings here and here) found no significant effect on several measures of cognition and school performance among primarily middle socioeconomic class children aged 5-12 years — while another longitudinal study of children in urban, lower socioeconomic means observed poorer reading and spelling scores and lower teacher-perceived school performance.

Low birth weight:

Several studies (here and here) have looked into this. When marijuana use was evaluated at the big picture level, there was no association between marijuana use and an increased risk of low birth weight.

However, when broken down into some use (less than weekly) versus heavy use (at least weekly), heavy users were more likely to have infants with a low birth weight.

Preterm birth:

Similar and potentially related to the investigations evaluating for low birth weight, heavy marijuana users were at increased risk of preterm birth.

But when the study results were broken down by tobacco use, marijuana alone was not associated with an increased risk of preterm birth.

Of note, there are other individual studies and reviews that have found no increase in preterm birth regardless of simultaneous tobacco use.

Stillbirth:

Currently, available evidence shows a slightly increased risk of stillbirth among marijuana users. However, the results in this study could not be adjusted for tobacco use.

Smoking weed during pregnancy has similar effects to smoking cigarettes

Dr. Eva Luo, MD, an OB-GYN and one of Modern Fertility’s medical advisors, adds that smoking marijuana (as opposed to other forms of consumption, like edibles) has similar effects on fetal development to smoking cigarettes. When smoked, Dr. Luo explains, marijuana can cause lung injury and decreased levels of oxygen in the body — which can ultimately affect the amount of oxygen reaching the growing fetus. Longer term, marijuana smoke contains the same respiratory disease-causing and carcinogenic toxins as tobacco smoke.

Marijuana isn't recommended for non-recreational use either

What about marijuana use during pregnancy to relieve nausea in the first trimester or manage anxiety and depression? "There is no evidence to support the efficacy of marijuana for these conditions in pregnancy and it's not recommended as treatment for pregnant women," says Dr. Luo. "I try to redirect patients to known safer alternatives. If a patient is using marijuana for other medical reasons, it's a discussion about the risks and benefits." If you're using marijuana for treatment of a medical condition, talk to your OB-GYN or fertility specialist about the risks and benefits of continuing the use of marijuana as you attempt to conceive and through pregnancy.

Safety aside, there are also some legal considerations

Dr. Luo says that even in states where marijuana is legal, some hospitals test babies after birth for drugs. If your baby tests positive for THC at birth, some states have laws that say child protective services must be notified.

Even with the sometimes conflicting findings above, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends people avoid using cannabis during pregnancy as well as while breastfeeding/chestfeeding.

Marijuana’s impacts on male fertility

As we continue learning about cannabis and the female reproductive system, what about weed and male fertility? Dr. Rashmi Kudesia, a reproductive endocrinologist at CCRM Fertility, tells us that we’re still finding things out about the medicinal and/or recreational drug: “We don’t know the impacts of these substances on a cellular level for sperm,” but there is a potential link with infertility and reproductive dysfunction.

A 2019 systematic review that examined known effects of the use of cannabis on sperm quality outlines some of those concerns in addition to some mixed results:

Sperm count: In studies of long-term marijuana use in humans and animals, researchers found a connection between lower sperm count and reductions in sperm concentration (the amount of sperm in 1 milliliter of ejaculate). Importantly, studies suggest that the more someone with sperm uses marijuana (i.e., how many joints they smoke on a weekly basis), the lower their sperm count.

Sperm morphology and sperm motility: Previous research also found marijuana smokers’ sperm to have higher rates of abnormal morphology (or shape, which can hinder their ability to swim and reach the egg) and reduced motility, or ability to move — something that can also impact whether or not they're able to fertilize an egg.

Male reproductive hormones: Marijuana’s effects on FSH and testosterone are mixed, but studies show it can lower LH.

Despite weed’s potential impacts on sperm quality, research so far hasn't discovered any effect on sperm’s genetic material. So, if you conceive, pregnancy loss and fetal development issues are not likely to be caused by a male partner or sperm donor's marijuana use.

The bottom line

If you’re a cannabis user who is pregnant, actively trying to conceive, or thinking about getting pregnant in the future, it’s important to speak with your healthcare provider about your cannabis usage to help you move forward in the safest way possible.

The truth is, there aren't enough recent studies with large (human) sample sizes to conclusively know how marijuana impacts fertility — especially in the long term. What we know right now demonstrates a need for more research. Still, since there's a possibility that marijuana could impact your chances of conception, avoiding it out of an abundance of caution is the move recommended by ACOG. Ultimately, though, cannabis is most likely to be a risk during pregnancy.

Thankfully, researchers are on the case on all fronts — and we’ll be keeping our eyes peeled for more committee opinions from governing organizations like ACOG. We know that this expansive info (or lack thereof) is pretty confusing, so we’ll be updating you with new cannabis research as it's made available.

This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Eva Marie Luo, an OB-GYN at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a Health Policy and Management Fellow at Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians, the physicians organization affiliated with the Beth Israel-Lahey Health System.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.