Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

At Modern Fertility, our aim is to always be a neutral, judgment-free resource for you to better understand your options as you plan for your future. One of these options may be induced abortion, which about 1 in 4 people with ovaries in the US will have by the time they're 45.

If you've had an induced abortion in the past or you're planning on having one soon, you might be wondering what impact, if any, it could have on your future fertility. We'll unpack the research below, but here's the biggest takeaway: Medical experts and researchers agree that induced abortion has no effect on future fertility.

It's perfectly understandable to have questions about abortion — we're using this article to help you get answers and make the right decisions for you. Before we jump in, here's a brief summary of what we’ll cover:

Abortion, when supported by the healthcare system, is a safe way to terminate a pregnancy.

Abortion options in the first trimester include a procedural abortion called vacuum aspiration and a medication abortion (aka the abortion pill). Right now, Texas is the only state that prohibits abortions during the first trimester.

In the second trimester, abortion options include dilation and evacuation (D&E) and induction abortion, both of which happen in a clinic or hospital. 42 states have bans on abortions after 20 weeks, unless the pregnant person's life or health is at risk.

Abortions after 24 weeks are generally available only if the pregnant person’s life or health are at risk, or in cases of severe fetal anomaly. There are very few providers of abortions later in pregnancy and these rare cases account for <1% of all abortions in the US.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that having an abortion will not impact your fertility, and decades of research back this up. Ovulation can return as quickly as three weeks after an abortion.

Studies have identified a possible link between having more than one abortion and adverse fetal outcomes like preterm birth and low birthweight, but researchers haven't been able to establish that this finding (rather than confounding factors) actually caused these issues.

Keep reading to dive deeper into abortion options, abortion safety and possible risks, and what the research says about abortion and fertility.

First things first: What exactly is an abortion?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the leading academic body of OB-GYNs, defines induced abortion as the termination of an existing pregnancy through medication or a medical procedure (both of which are safe and highly effective). Doctors also use the term spontaneous abortion, which is a miscarriage before 20 weeks. If a miscarriage is incomplete (some of the tissue remains inside), doctors will use the same medication and surgical procedures performed for induced abortion to help complete the process.

(We recognize that "spontaneous abortion" might be a difficult term to hear in the context of an intended pregnancy, but it's useful to make this distinction because the term may come up in conversations with a healthcare provider about health history.)

What types of abortions happen during the first trimester?

Before we get into specifics about abortion in the first trimester, it's important to understand how pregnancy is dated. Since the exact time of conception is challenging to pinpoint, doctors use your last menstrual period (LMP) to count the weeks of your pregnancy. The "gestational age" of a pregnancy technically starts on the first day of your last period, so when you miss your next period, you're already considered four weeks pregnant — even though for a 28-day cycle, you only conceived two weeks prior (we know, it’s confusing). The first trimester covers the first day of your LMP through 13 weeks and six days of pregnancy.

According to ACOG, 80% of abortions happen in the first trimester — or before 13 weeks and six days of pregnancy. Depending on the clinic or hospital, a first-trimester abortion can be performed as early as the fifth week of gestation (two or more weeks after you ovulate). This is typically around the same time people may first notice a missed period or see a positive pregnancy test result. Currently, only one state, Texas, has a ban on abortions in the first trimester (after six weeks).

During most of the first trimester, abortion can be performed via procedural (aka surgical) abortion or medication abortion (aka the abortion pill). After 10 weeks gestation, the medication option becomes less effective.

Procedural abortion

A procedural abortion called vacuum aspiration is typically offered up to 14 weeks of pregnancy. Vacuum aspiration is a safe, in-clinic procedure performed by a trained healthcare provider. The procedure involves the following steps:

The provider places a speculum inside the vagina to gently hold it open and safely visualize the cervix.

Typically, the cervix will need to be dilated (aka opened) with medication or dilating tools before and during the procedure.

The provider inserts a thin, plastic tube through the cervix and into the uterus, before attaching it to a suction or vacuum pump to remove the pregnancy.

Pain and numbing medications, as well as antibiotics, may be prescribed to make sure the patient is comfortable and to make infection less likely.

People will typically go home on the same day of the appointment.

After a vacuum aspiration, people may experience some soreness and cramping for a few days, and light bleeding or spotting for up to two weeks.

What's important to note here is that you may sometimes hear vacuum aspiration referred to colloquially as dilation and curettage (D&C). "A D&C was the procedure of choice before newer and safer vacuum technology became the norm in the 1970s," explains OB-GYN and Modern Fertility medical advisor Dr. Jenn Conti, MD, MS, MSc. "But the term has stuck around and is still used interchangeably by doctors to describe any first-trimester surgical procedure." Even though these terms might be used interchangeably, the actual D&C procedure is less commonly performed today.

Medication abortion

Medication abortion can be prescribed by a healthcare provider at a clinic — or, depending on where people live, through a telemedicine appointment for a self-managed abortion at home (research shows telemedicine administration of these medications is also safe and effective). While medication abortion is often called the abortion pill, it actually requires one pill (mifepristone) followed by multiple pills (misoprostol):

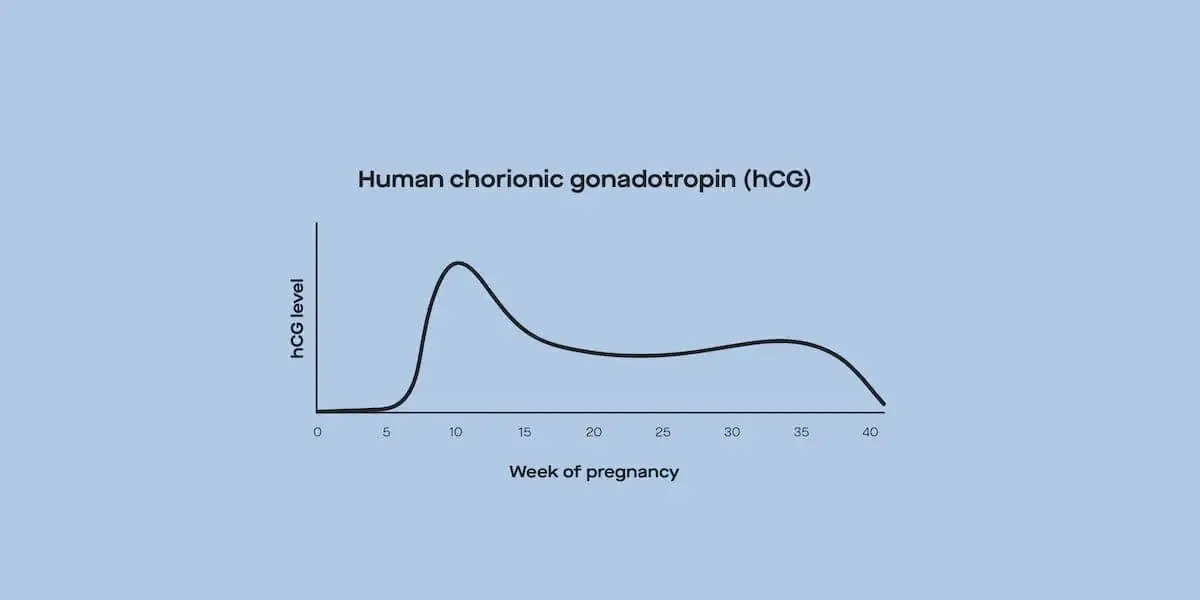

Mifepristone works by blocking the activity of progesterone, a hormone that rises during early pregnancy. This stops the pregnancy from growing.

Misoprostol works by inducing cramping to open the cervix and empty the uterus.

Mifepristone and misoprostol are approved by the FDA through ten weeks of pregnancy. The medications may cause heavy bleeding, nausea, vomiting, fever, or chills. People may be prescribed pain medication or recommended over-the-counter meds to help with side effects. Following up with a healthcare provider after using the medication is advised.

(Important reminder: No, Plan B is not the same thing as the abortion medications. Mifepristone is an anti-progesterone and Plan B is an actual progesterone — meaning they're exact opposites.)

What types of abortions happen during the second trimester?

About 1 in 10 abortions happen in the second trimester, before 20 weeks of pregnancy — and about 1 in 100 happen at or after 21 weeks. (Abortions after 21 weeks typically cost more than earlier procedures, and often involve travel and potentially lost wages. Also, a smaller percentage of clinics and providers can perform them.)

What's important to know here is that 42 states have restrictions on abortions when the pregnancy is considered "viable" (meaning a fetus would have a 50% chance of surviving with NICU support if delivered), unless a pregnant person's life or health is endangered. Healthcare providers generally consider the timeline for "viability" to start around 23-24 weeks — and the chance of survival if delivery occurs before 23 weeks is about 5%-6%.

In the second trimester, the procedural abortion method dilation and evacuation (D&E) is most common, but induction abortion (another type of medication abortion) is also an option.

Procedural abortion

Second-trimester abortions are typically performed through dilation and evacuation (D&E), which is a safe procedure — and the medically preferred approach to abortion after 14 weeks. D&E involves the following steps:

Before the procedure, sometimes the day prior, the cervix will be dilated with medication or tiny expandable dilators called laminaria.

On the day of the actual procedure, if dilators were inserted into the cervix, they'll be removed. Further dilation, if needed, may also happen.

The provider uses a suction device and other medical instruments to remove the pregnancy and any remaining tissue. There are no incisions on the cervix or uterus.

Patients may undergo the procedure with anesthesia, and may also be prescribed pain medications and antibiotics.

People will most likely go home on the same day as the procedure.

After D&E, people may experience soreness and cramping for a few days, and bleeding and spotting for up to two weeks. Over-the-counter pain meds, in addition to any prescribed medications, can also help with soreness and cramping.

Induction abortion

Medication abortion in the second trimester is different from the abortion pills in the first trimester. Second-trimester medication abortions, which are called induction abortions, are done in the clinic or hospital so the patient can be monitored throughout the procedure:

The provider will give medications intravaginally, orally, by injection into the uterus, or through an IV. (These are typically mifepristone and misoprostol, but sometimes mifepristone and other inducing agents like oxytocin or prostaglandin analogues.)

Pain medication is commonly given, and an epidural may also be an option.

The procedure may take between 12 and 24 hours.

Whether or not people go home the same day will be decided in a conversation with the healthcare provider.

After an induction procedure, people may experience nausea, fever, vomiting, bleeding, and diarrhea — but healthcare providers can prescribe medication to help with these side effects.

What types of abortions happen during the third trimester?

Unless a pregnant person's life or health is endangered, or a significant fetal anomaly is present, abortions in the third trimester are either banned or fall under "viability" restrictions in 43 states. Since the third trimester begins after 28 weeks of pregnancy, that means third-trimester abortions are banned in those 43 states. In states and instances where third-trimester abortion is allowed, the procedure is typically very time intensive — and only a very small number of clinics are trained to perform it. Abortions in the third trimester are incredibly rare, accounting for <1% of all procedures, and only done via labor induction after first using specialized medication to ensure the pregnancy is not viable.

Can having an abortion affect future fertility? The research says no

First, it's important to understand that the belief that abortion could impact fertility is grounded in the very real history of infertility caused by unsafe underground abortions.

"There is no plausible reason to associate infertility with abortion outside of rare cases of severe uterine damage and severe infections/PID (more on this in a bit) — like those of the 'abortion sepsis wards' in hospitals from the 1960s," Dr. Conti explains. Outside of some of the rare complications we'll cover below, "a person having an abortion has already proven they can get pregnant and the simple act of the uterus evacuating a pregnancy without complication doesn't affect the ability to get pregnant again."

ACOG confirms that having an abortion doesn't increase the risk of infertility. In 2018, a panel organized by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) examined all of the available research and backed up ACOG's position. Their report highlights a 2016 study published in BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth as the only one that met its selection criteria: This study examined the Finnish National Birth Registry data from 2008 to 2010 against the Induced Abortion Registry data from 1983 to 2007. In reviewing the data from follow-up visits for the 5,167 women who were eligible for the study and had past abortions, researchers found no evidence of a link between abortion and secondary infertility. ("Secondary infertility" is used here because an abortion implies prior ability to get pregnant.)

NASEM left out any studies published before to 2000 so the report was representative of current abortion practices, but the bulk of the research around abortion and future fertility took place in the '80s and '90s. Even so, older studies also support what the 2016 one found:

A 1990 review published in Fertility and Sterility (the official journal of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine) included all of the data on abortion and future fertility that was available at the time. Their findings showed that legal abortions (ones performed by "well-trained and experienced physicians") have little long-term impact on health. There was a comparable rate of secondary infertility in those who had past abortions and those who hadn't.

Another review from 1982, which was published in Epidemiological Reviews, analyzed the data from over 200 epidemiological reports. They identified that secondary infertility may be a "rare late effect" of complicated abortion — but this effect was so infrequent that it didn't indicate an increased risk. There was one exception in the data: People who had undergone abortions in Greece, where abortion was illegal (i.e., unsafe), had a notably increased risk of infertility.

Another way to understand abortion's impact on fertility (or lack thereof) is how long it takes for ovulation to return after a procedure. A quick refresh on why ovulation is key for conception: Ovulation, which is the time in your menstrual cycle when an ovary releases an egg, is central to making sure an egg is available for fertilization. According to a paper published in 2011 in the journal Contraception, studies demonstrate that ovulation can resume as early as three weeks after an abortion. ACOG says that some people may start new birth control the same day they have the procedure because of how quickly someone can get pregnant after an abortion.

Abortion complications and future fertility

Complications after safe abortions are extremely rare: According to one retrospective observational cohort study, the major complication rate (defined in the study as "serious unexpected adverse events requiring hospital admission, surgery, or blood transfusion") was 0.31% for medication abortion, 0.16% for first-trimester aspiration abortion, and 0.41% for second-trimester or later procedures.

To detect any possible abortion complications, ACOG advises reaching out to your healthcare provider if you experience severe abdominal/back pain, heavy vaginal bleeding (i.e., soaking two pads every hour for two hours in a row), foul-smelling vaginal discharge, or fever.

Asherman's syndrome: One possible complication after certain types of abortion is a rare acquired condition (meaning it's not something you're born with) called Asherman's syndrome, which is marked by adhesions inside the uterus. Asherman’s may occur in up to 15%-20% of people who undergo D&C to induce abortion or after a miscarriage.

"The true prevalence of Asherman's is difficult to establish because what estimates we do have are based on cases done by the older D&C procedure, not the gentler suction approach that is used today," says Dr. Conti. The suction approach "doesn’t scrape or disrupt the uterine lining and lead to this scar tissue." Reminder that although D&C is sometimes used interchangeably with standard first-trimester abortion procedures, the actual D&C procedure (which is different from D&E in terms of the tools used) has largely been replaced by the safer and faster vacuum aspiration in the first trimester.

Asherman's can impact your fertility, but it doesn't always — and when it does, surgical treatment can help you bring back your regular menstrual cycles and make conception more likely.

The spreading of existing infections: Another possible complication is the spreading of existing, untreated infections (like chlamydia, gonorrhea, or bacterial vaginosis) to the upper reproductive tract, which could then lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and cause infertility. Routine testing and early treatment of these infections will help prevent the bacteria from spreading and causing issues.

Can having an abortion impact future pregnancies in any other ways?

To help answer this question, we'll return to the 2016 study published in BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth because it's the most recent and comprehensive review on abortion and future pregnancy. The researchers found no association between a past abortion and pregnancy complications like preeclampsia, hypertension, gestational diabetes, and preterm premature rupture of membranes (rupture of the amniotic sac before labor).

We can also look to the 1982 review for their findings on pregnancy complications and adverse fetal outcomes (though it's important to remember the caveat that older studies don't reflect present-day practices):

The researchers found that while ectopic pregnancy (when an egg gets fertilized and grows outside of the uterus) could be a rare, late-onset effect of an abortion that was complicated by infection or trauma, this happened so infrequently that they didn't acknowledge it as a significant risk that could actually be associated with the procedure.

Similarly, midtrimester spontaneous abortion (a pregnancy loss in the second trimester) rates weren't higher for people who had a past abortion when compared to those who were pregnant for the first time.

There were similar rates of preterm labor among those who'd had a past abortion compared to those who didn't, as well as rates of infant morbidity (disease) and mortality (death).

Does the number of past abortions play a role in future complications? Maybe. One 2012 study published in Human Reproduction matched 1996-2008 births in the Medical Birth Register in Finland against the Abortion Register from 1983-2008 and investigated a total of 300,858 births to first-time parents. The researchers found that the rates of very preterm birth and very low birthweight for their first birth increased as the number of prior abortions someone had increased (based on data from mostly surgical abortions).

That said, the researchers noted two important disclaimers:

Observational studies like this one can't actually determine causality — they can only show associations. There could be other confounding factors that make these outcomes more likely for people who've had multiple abortions. "For example, what if people who have more than one abortion are also less likely to have adequate access to contraception and, as a result, have shorter interpregnancy intervals between pregnancies, which is known to increase risk of preterm birth?" says Dr. Conti. "It’s the short interpregnancy interval that likely increases risk, not the second or third abortion."

88% of the abortions represented in the data were procedural abortions, not medication abortions.

Are there any other risks associated with having an abortion?

Abortion is a safe procedure and, as we mentioned earlier, complications are rare. According to ACOG, having an abortion will not increase your risk of breast cancer or depression — "despite what many state laws mandate healthcare providers to tell their patients," adds Dr. Conti. While you may have heard about a link between abortion and breast cancer or mental health issues in the past, that same 2018 panel from NASEM we talked about in the fertility section examined all of the available research and affirmed ACOG's position.

However, like with any medical procedure you might undergo, there are possible risks. We already touched on infection, but in very rare cases, there may be what's called an incomplete abortion — this means the pregnancy wasn't completely removed from the uterus. Incomplete abortions are more common after medication abortion than they are procedural abortion, and increase with gestational age. In the event of an incomplete abortion, you may need a follow-up procedure or more medication. "Only 1% of surgical procedures and about 5% of medication abortions will need additional follow-up to remove remaining tissue inside the uterus," says Dr. Conti. "This rate also increases slightly with an incomplete miscarriage because the old pregnancy tissue becomes stickier and more difficult to expel the longer it remains inside."

The bottom line

If you've had an abortion or are considering one now, know that research shows it's a safe way to terminate a pregnancy — and it won't influence your fertility in the future.

As with anything related to fertility, it's important to understand your options and connect with a supportive healthcare provider who's an expert in whatever topic you're addressing. When you're planning ahead or considering your choices, Modern Fertility is always here to help you get the clinically sound information you need.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.