Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

The thyroid is one small gland with a huge amount of power. Thyroid function can impact everything from sleep to stress, and even fertility. Here’s how you can check in with your thyroid and what you can expect to learn from your results.

Is there a thyroid test?

The first step when it comes to checking in with your thyroid gland is with a TSH blood test. The test looks into how much thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) your body is producing and gives you insight into thyroid health.

Why is TSH so important? When the thyroid is overactive or underactive, the brain gland sends a helpful message (via TSH) to adjust the amount of thyroid hormone released into the bloodstream.

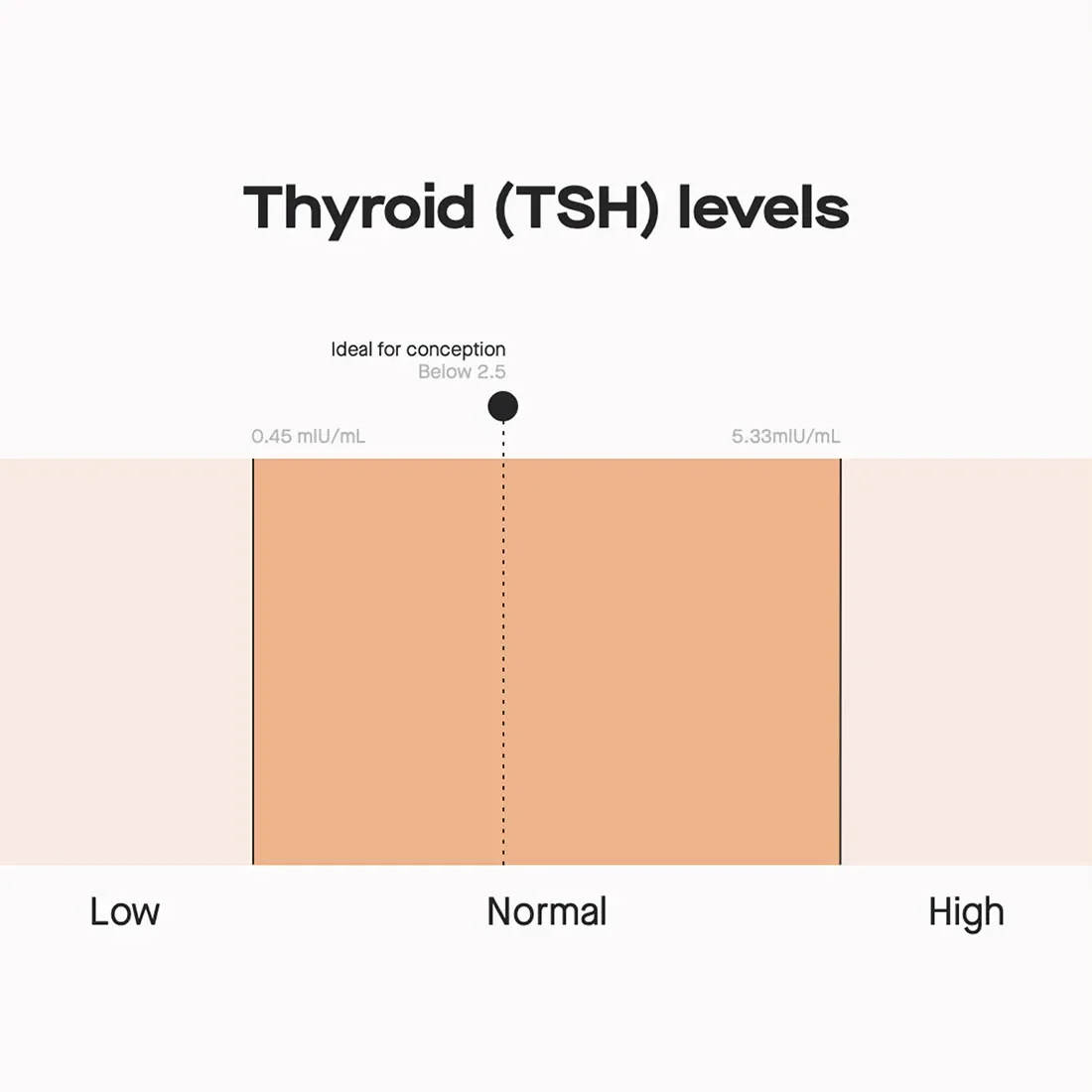

Higher TSH levels indicate an underactive thyroid, and lower TSH levels indicate an overactive thyroid.

Which thyroid hormones should be tested?

At Modern Fertility, we always measure your TSH — and if your results show that you might have thyroid dysfunction, we’ll retest your TSH and follow up with an fT4 (free thyroxine) test, another important thyroid hormone, at no additional cost.

About a third of Modern Fertility hormone test users discover a thyroid hormone result that’s worth discussing with a doctor before trying to get pregnant. (If you’re thinking about having kids one day, keep in mind that medical guidelines recommend having a TSH level below 2.5 uIU/mL prior to conception.)

Thyroid conditions are very treatable, so checking in with your levels can help you stay on top of any future problems.

Thyroid hormone tests often measure both TSH and fT4 levels.

What is considered low TSH in women?

If your test comes back with a TSH level below .4 uIU/mL, that typically suggests an overactive thyroid — aka hyperthyroidism.

If you have hyperthyroidism, you might experience the following symptoms:

Unintentional or unexpected weight loss

Rapid heartbeat, or tachycardia

Irregular heartbeat, or arrhythmia

Pounding heartbeat, or palpitations

Increased appetite

Anxiety and irritability

A slight tremor in the hands or fingers

Sweating

Changes in your menstrual cycle

Changes in bowel movements

An enlarged thyroid gland in your neck (or goiter)

Skin thinning and brittle hair

Chart of TSH levels and the low, normal and high range.

What is considered a high TSH level in women?

If your test comes back with a TSH level above 4.0 uIU/mL, that typically suggests an underactive thyroid — aka hypothyroidism.

If you have hypothyroidism, you might experience the following symptoms:

Fatigue

Increased sensitivity to cold

Constipation

Dry skin

Weight gain

A puffy face

Voice hoarseness

Muscle weakness, aches, and stiffness

Elevated blood cholesterol level

Joints pain or swelling

Heavier or irregular menstrual periods

Coarse hair and hair loss

Brittle nails

Slowed heart rate

Depression

Impaired memory

Enlarged thyroid gland (goiter)

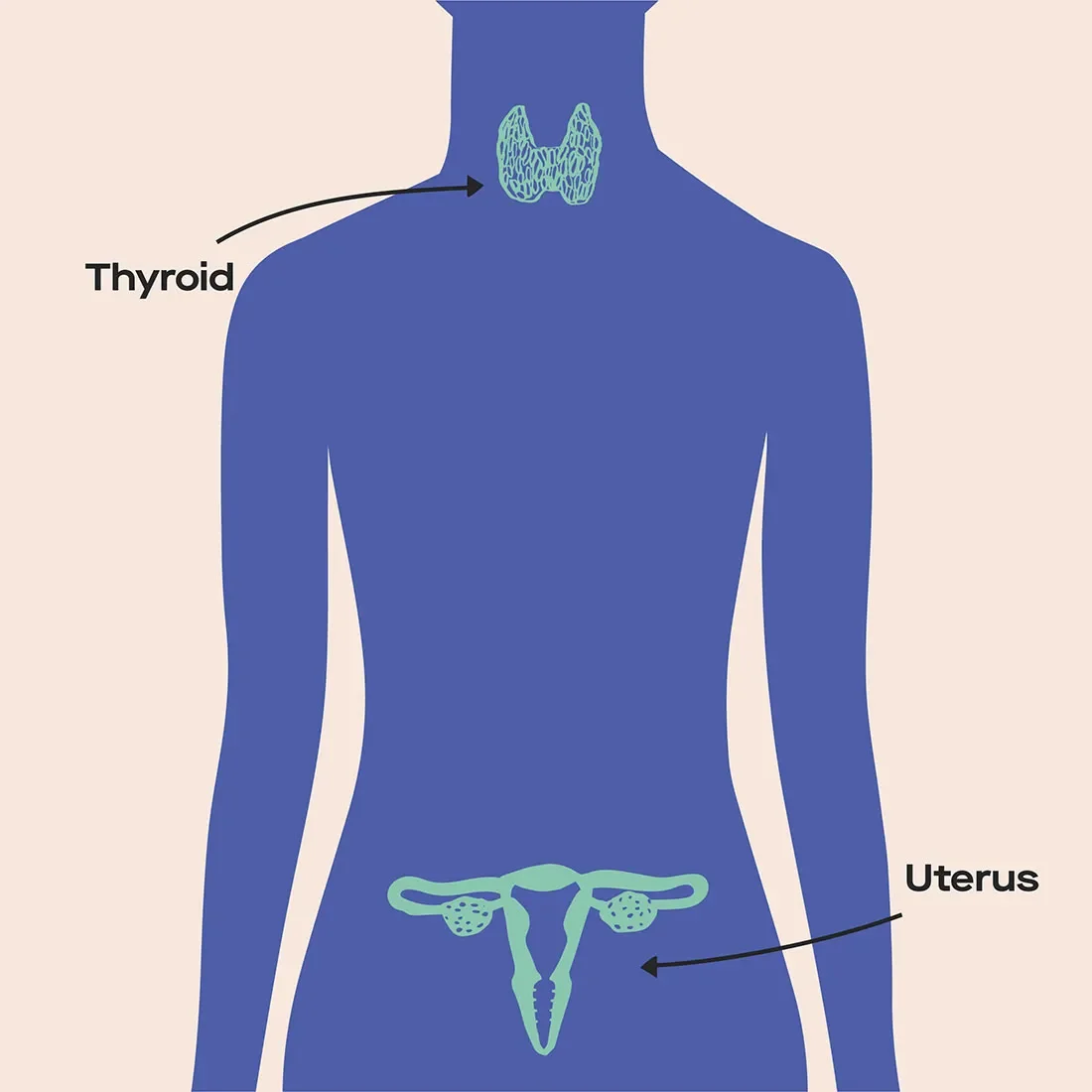

Thyroid and fertility: What’s the connection?

Studies show that when there are higher or lower levels of thyroid hormones, it can alter reproductive hormones and disrupt the menstrual cycle — which makes conception more difficult.

But just because you have hypo- or hyperthyroidism doesn’t mean you can’t get pregnant. In one study of a group of almost 400 women with infertility, 24% of participants were found to have hypothyroidism — but within a year of treatment, 76% were able to conceive.

Thyroid hormone levels can have a big impact on fertility.

What’s the easiest way to test your thyroid levels?

Modern Fertility measures your thyroid levels using the same test that a specialist at a fertility clinic would use — but you can do it from the comfort of your couch and for a fraction of the price.

With our test, you’ll also get access to:

Physician-designed reports based on your results, including one focused on thyroid hormone levels and any health implications of your results

A free 1:1 consult with our fertility nurse

Online tools to track hormone changes over time and help you plan your timeline for kids

Access to our live Q&As

An invite to the Modern Community to connect with others and get your questions answered

Testing your thyroid hormones is easy (and affordable) with Modern Fertility.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Verma, I., Sood, R., Juneja, S., & Kaur, S. (2012). Prevalence of hypothyroidism in infertile women and evaluation of response of treatment for hypothyroidism on infertility. International journal of applied & basic medical research , 2 (1), 17–19. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-516X.96795