Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Lifestyle recommendations for managing polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), like “eating well” and “moving more,” are tossed around like hot potatoes, with little in-depth analysis of what any of that actually entails for someone dealing with PCOS. Google it and you’ll find recommendations for every type of eating plan under the sun. It begs the question: Is there a “PCOS diet,” or a way of eating that works best in managing symptoms for people with PCOS?

Frustratingly, modern medicine does not currently have a cure for PCOS, pharmacological or lifestyle-based. As a result, medicine’s focus for PCOS is on reducing future issues like diabetes, fertility challenges and endometrial cancer. Further, PCOS presents differently from person to person, making it exceedingly challenging to find one treatment that works across the board.

What we do know is that two of the three criteria for diagnosing PCOS, elevated androgen levels (think high levels of testosterone) and anovulation (a lack of ovulation), are both fundamentally issues of hormonal imbalance — and that’s where nutrition comes in.

Since what you eat is one place where you can exert some control, we’re diving into three main takeaways from the research around nutrition and PCOS:

Reduce carb intake (this doesn't mean you can't have any carbs, just consider choosing a small portion per meal). Choose complex, unrefined carbs with a lot of fiber — think whole grains like whole wheat bread or brown rice.

Choose "anti-inflammatory" foods, including 8-10 services of veggies per day, fats from olive oil or avocados and nuts, lean proteins, and high-antioxidant foods like berries.

Overall, try to reduce saturated or trans fats, processed foods, alcohol, and caffeine.

The role of nutrition in PCOS management

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 Guidelines recommend nutrition and exercise as first-line treatment for PCOS. This recommendation is based on a substantial body of research establishing nutrition as a powerful player in reducing insulin resistance and bringing down inflammation, which has trickle-down benefits by lowering elevated androgen levels, and ultimately, improving unwanted symptoms and side effects of PCOS (like menstrual irregularity and infertility).

When it comes to improving insulin resistance and inflammation, all in the name of balancing levels of sex hormones (like testosterone), key nutrients (vitamin D and magnesium) are important only after balanced, PCOS-friendly eating has already been established. The most well studied of these PCOS-friendly eating patterns can be boiled down into low carb/high protein and an anti-inflammatory approach.

Low-carb nutritional approaches

Carbohydrates, unlike proteins and fats, spike your blood sugar levels. Rising blood sugar levels signal the pancreas to produce insulin. Insulin is a hormone that shows up on the job to “unlock” cells and let the sugar in from your bloodstream. Problems arise when blood sugar levels are too high, too frequently. When this occurs, the pancreas responds by producing more and more insulin, kicking off a domino effect of hormonal imbalance.

Cells grow desensitized to the constant blast of insulin, a condition called “insulin resistance.” Essentially, this means that insulin can’t shuttle sugar from the blood into the cells where it’s needed. As a result, sugar and insulin remain circulating in the bloodstream, increasing the risk for developing type 2 diabetes and developing into a condition called hyperinsulinemia (i.e., too much insulin).

Why does all of this matter?

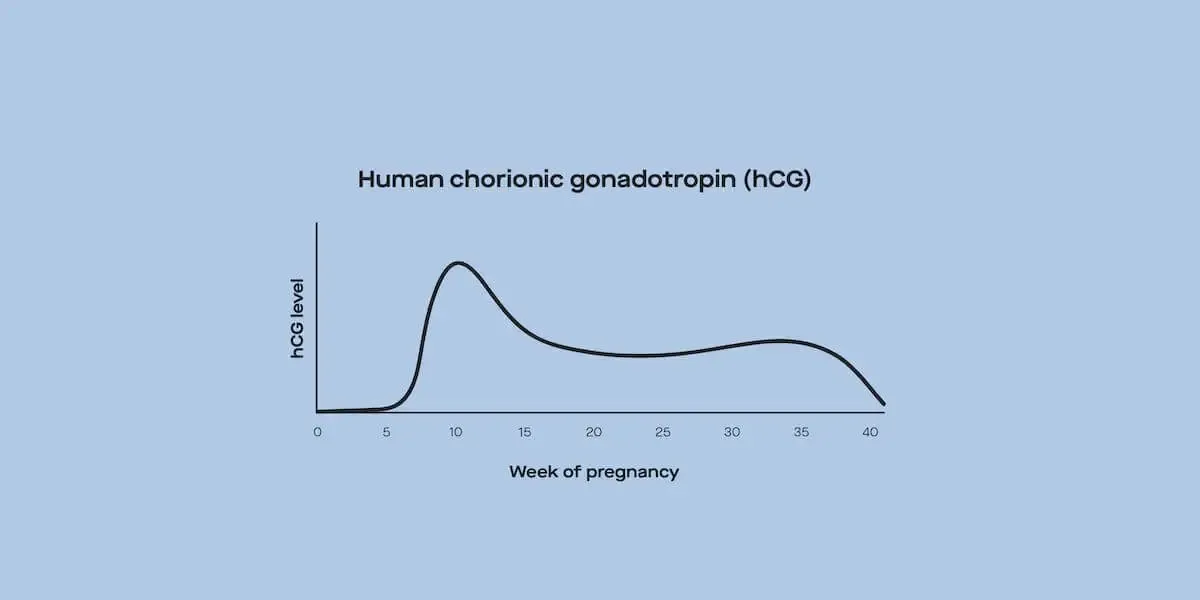

Hyperinsulinemia is a primary driver of the elevated androgen levels that characterize PCOS. Insulin resistance triggers excess androgen production from your ovaries, blocks ovarian follicle development and ovulation, interferes with luteinizing hormone (LH) production from your pituitary gland — and an estimated 70% of people with ovaries living with PCOS have it.

Although there are genetic and environmental contributors outside of our control, insulin resistance is considered largely controllable through lifestyle modifications — which brings us back to carbs.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that controlling insulin resistance, in turn, improves hormonal balance enough to restore menstrual regularity. Further research, including a meta-analysis comprising eight clinical trials, found that following a low-carb diet for at least four weeks increased insulin sensitivity, improved ratios of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) to LH, and lowered elevated testosterone levels.

Does this mean people with PCOS can’t eat carbs?

Not at all! Many of the clinical trials in the aforementioned meta-analysis saw benefits among participants still eating up to 40% of their calories from carbs. For reference, the standard American diet typically includes 50% or more of calories coming from carbs.

The take-home here is that you may be able to improve insulin resistance, and subsequently lower androgen levels, by reducing carbohydrate intake. You don’t have to cut out all of the bread and pasta. Instead, start by eating just one source of carb per meal — i.e., bread or pasta, not both in the same meal.

Choosing “better” carbs

It’s not just about controlling the amount of carbs you eat — the type of carb also counts. Complex, unrefined carbs with a lot of fiber do not cause the same rapid blood sugar spikes as do their refined counterparts (think whole grain bread vs. white).

The glycemic index ranks foods by how quickly they spike your blood sugar. A high glycemic-index (GI) food, like white rice, raises your blood sugar rapidly compared to a low GI food, like lentils. A clinical trial including 100 people with PCOS found that after 12 months, those primarily eating a low GI foods improved insulin sensitivity and menstrual regularity more than those following an otherwise “healthy” way of eating.

How to apply these learnings to your life

No need to memorize the glycemic index. Instead, simply go for foods in their least processed, most fiber-full forms:

Think more brown rice and bread and less of their white counterparts.

More corn on the cob and less corn syrup.

More rolled oats and less instant oatmeal.

More baked potatoes and less potato chips.

Anti-inflammatory eating

Is it all about carbs? Not entirely. There’s also promising research supporting an anti-inflammatory nutrition approach. Both PCOS and insulin resistance are marked by chronic, low-grade inflammation (read more here and here). Reducing inflammation through an “anti-inflammatory diet,” in turn, has been shown to improve clinical biomarkers associated with PCOS, including improved insulin sensitivity and better hormone balance. Despite the dearth of randomized control trials proving the benefits of this dietary strategy specifically for the treatment of PCOS, there is ample research (here and here) showing that an anti-inflammatory diet does any body good.

Before continuing, a quick clarification is in order. “Anti-inflammatory diet” is often used interchangeably with the “Mediterranean diet.” While the “Mediterranean diet” is far and away the most well-studied version of an anti-inflammatory approach, this nutrition approach does not have to be that culturally confined. People from all over the world can follow the general anti-inflammatory principles outlined below and still maintain their culture’s culinary traditions.

Another plus for an anti-inflammatory approach is that there aren’t a lot of mundane rules to follow or long lists of foods to memorize.

How to apply these learnings to your life

Have lots of:

Fresh, brightly colored fruits and vegetables. Think 8-10 servings of vegetables per day in a rainbow of colors, like red peppers, pink grapefruit, orange sweet potatoes, yellow squash, dark leafy greens, blueberries, and purple cabbage.

Fats from olive oil/olives, avocadoes, nuts, and seeds.

Whole, fiber-full grains. (Not coincidentally, anti-inflammatory grains also happen to be the lower GI options.)

Lean protein, such as fish (ideally cold-water varieties like salmon), shellfish, beans, legumes, eggs, and lean cuts of chicken and turkey.

High-antioxidant foods like berries, turmeric, cinnamon, ginger, garlic, and green tea.

Have less:

Saturated fats or trans fats from packaged baked goods, full-fat dairy, and red meat.

Processed food. Go for a square (or two) of 70% dark chocolate over M&Ms, and have oatmeal or eggs rather than sugary cereals or sweetened yogurt.

Alcohol and caffeine. This one’s hard, but just know it isn’t an all or nothing kind of thing. A little bit of either, like one cup or glass per day, is not likely to cause massive inflammation — especially if paired with antioxidant-rich foods.

What’s weight got to do with it?

Doctors will often suggest weight loss as a way to manage PCOS, which is likely why so many of the studies cited in this article mention weight loss as one of the ways to measure the “success” of each nutritional plan in regards to PCOS. This recommendation stems from the fact that adipose tissue (aka body fat) is inherently more insulin resistant than muscle. Additionally, research consistently shows that 5-10% loss of body weight can improve PCOS symptoms, from infertility to acne to risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

The problem is that food and exercise aren’t the sole determinants of weight — and weight isn’t always completely within an individual’s control. That said, while the dietary strategies outlined above are often shown to support a reduced body-fat percentage, these ways of balanced eating allow you to focus on improving metabolic markers of health — like blood sugar and cholesterol levels — rather than an arbitrary number on the scale.

Nutrition is only one piece of the PCOS management puzzle

If there was a silver bullet way of eating that magically helped anyone with PCOS manage their symptoms and side effects, everyone would be doing it. Unfortunately, nutrition is never one-size-fits-all — and it’s only one way to treat PCOS. Other treatment options you may explore involve medications, like birth control pills to regulate hormones and metformin to manage higher blood sugar levels.

Keep in mind that managing PCOS is a life-long commitment, and any food changes you make for PCOS management won’t impact your condition immediately (nor is it easy to track the impact on a day-by-day basis). If you’re curious about how nutrition could play a role in the management of your PCOS, work with a registered dietitian who can translate scientific findings like the ones in this article into real-life solutions that work for your body and your life.

This article was written by Anna Bohnengel, MS, RD, LD, co-founder of Alavita Nutrition

This article was medically reviewed by Dr. Eva Marie Luo, an OB-GYN at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and a Health Policy and Management Fellow at Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians, the physicians organization affiliated with the Beth Israel-Lahey Health System.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.