Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Vitamin B12 is the largest and most complex of all the vitamins, and it does many vital jobs in your body. That’s why a B12 deficiency can be very damaging to your health. Find out if you might be at risk of deficiency, why you should get tested, and your options for bringing up your B12 levels.

What is vitamin B12 deficiency?

Vitamin B12 deficiency is a medical condition in which your blood and tissue levels of B12 are low. About 6% of adults younger than 60 years in the United States and the United Kingdom have vitamin B12 deficiency. The rate is closer to 20% in those older than 60 (USDA, 2019; Langan, 2017; HHS, 2021)

The only way to find out if you have a B12 deficiency is by having a blood (serum or plasma) test (Ankar, 2021).

What is vitamin B12, and why is it important for health?

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a nutrient in the B vitamin complex. It has the largest and most complex structure of any vitamin. It plays a number of different roles in your body (Linus Pauling, 2021):

It’s necessary for producing fatty acids and making red blood cells, as well as RNA and DNA.

It’s also vital for maintaining the nervous system because it helps form the myelin sheath that coats nerve cells.

Because vitamin B12 has such vital functions in many of your body’s systems, a deficiency can have very serious health effects.

Who is at risk of having vitamin B12 deficiency?

There are a number of risk factors for vitamin B12 deficiency. You may be deficient in vitamin B12 if you (USDA, 2019; Langan, 2017; HHS, 2021):

Are vegan or follow a strict vegetarian diet. Breast-fed babies of vegan women are also at risk.

Have had surgery of the stomach or intestine

Have a condition that interferes with nutrient absorption (called malabsorption), such as pernicious anemia, inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, or celiac disease

Have diabetes and have used metformin for more than four months

Have used proton pump inhibitors or histamine H2 blockers for more than 12 months

Are an older adult. One in five people over age 60 have a B12 deficiency, and B12 deficiency is even more common in people over age 75. As you get older, your stomach produces less hydrochloric acid, a condition called atrophic gastritis. Hydrochloric acid helps you to absorb B12, so having less of it makes B12 absorption difficult.

What are the symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency?

B12 deficiency symptoms can develop slowly over many years. That’s because large amounts of B12 are stored in your liver. Symptoms may not develop until the stored B12 is used up.

Because vitamin B12 is key in so many vital processes in your body, there are many possible symptoms of B12 deficiency (Langan, 2017):

Anemia (a low number of red blood cells)

Fatigue when physically active

Fast heart rate

Pale skin

Skin discoloration (hyperpigmentation) or loss of skin pigment (vitiligo)

Hair changes

Smooth tongue (glossitis)

Infertility

Nervous system problems (such as numbness, tingling, muscle weakness, problems walking)

Vision loss

Memory loss

Changes in behavior

Dementia, including episodes of psychosis (in cases of severe, long-term deficiency)

How is vitamin B12 deficiency diagnosed?

Testing for vitamin B12 deficiency is typically recommended only for people with one or more of the risk factors listed above.

The first test for B12 deficiency, and maybe the only one that will be needed, is a blood (serum or plasma) test. This test will include a complete blood cell count and a measurement of your serum vitamin B12 levels.

Most laboratories define vitamin B12 deficiency as (Ankar, 2021; HHS, 2021):

B12 levels lower than 200 or 250 pg/mL

If the results of the first test are unclear, then your healthcare provider may do further testing.

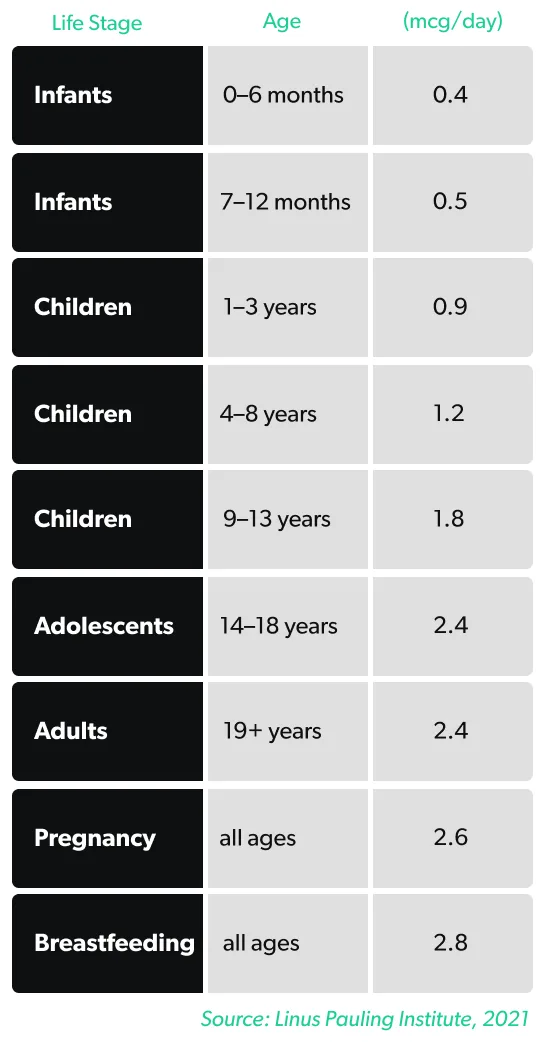

How much vitamin B12 do you need each day?

How much vitamin B12 you need depends on your life stage and other factors. Most people get all the B12 they need from a daily diet that includes meat, seafood, and dairy products, unless they have one or more of the risk factors listed above.

What is the treatment for vitamin B12 deficiency?

The type of treatment you get may depend on the cause of the deficiency.

Treatment for people with pernicious anemia or absorption problems includes (HHS, 2021):

Injections into a muscle or oral (swallowed) vitamin B12 therapy

People with nervous system symptoms (like numbness, muscle weakness, or trouble walking) may be given injections every other day for up to three weeks or until there’s no further improvement

People without nervous system symptoms may be given injections three times per week for two weeks

People who don’t eat foods from animals have several options for getting enough vitamin B12 (HHS, 2021):

Change your diet to include food supplemented with vitamin B12. Fortified foods include breakfast cereals and grains, vegan spreads, non-dairy milk, meat substitutes, and nutritional yeast. (Check the labels, though, because not all these foods are fortified with B12).

Take a B12 supplement.

Get B12 injections.

Of course, if you may have a vitamin B12 deficiency, it is best to work with your healthcare provider to find the treatment approach that is best for you.

What are vitamin B12 supplements?

Vitamin B12 is available as an over-the-counter (OTC) supplement and also as a prescription medicine.

OTC vitamin B12 supplements

The most common form of vitamin B12 in dietary supplements is cyanocobalamin. Other forms are adenosylcobalamin, methylcobalamin, and hydroxycobalamin. Unlike some other vitamin supplements, vitamin B12 supplements have excellent bioavailability, meaning a good amount gets into your bloodstream so your body can use it. Vitamin B12’s bioavailability from dietary supplements is about 50% higher than its bioavailablity from food sources (HHS, 2021).

Vitamin B12 is available as oral (swallowed) supplements in the form of pills and tablets, as well as sublingual (placed under the tongue) supplements in the form of tablets, lozenges, liquids, and sprays. The oral and sublingual forms of vitamin B12 are equally effective.

Vitamin B12 supplements are also available in different formulations:

Multivitamin/mineral supplements usually contain 5–25 mcg of B12

B-complex vitamin supplements generally contain 50–500 mcg of B12

Stand-alone vitamin B12 supplements typically contain 500–1,000 mcg of B12

Prescription vitamin B12 supplements

Prescription vitamin B12 is usually injected directly into a muscle so that it doesn’t have to go through the digestive system. Intramuscular injections can be given to people with severe deficiencies due to conditions that make them unable to absorb B12 through their intestines (such as tropical sprue and pancreatic insufficiency). Prescription vitamin B12 is also available as a nasal spray (HHS, 2021).

What are the benefits of supplementing vitamin B12?

If you have low levels of vitamin B12, the benefits of supplementing may include (HHS, 2021):

Increasing energy by helping to form red blood cells

In pregnant women, preventing major congenital anomalies in an unborn child

Reducing risk of macular degeneration

Improving mood and relieving depression (Sangle, 2020)

Improving memory and slowing mental decline (Oulhaj, 2016)

What are vitamin B12 side effects?

Some studies have found that supplementing with B12 may increase your risk of colorectal cancer and lung cancer (Oliai Araghi, 2019; Fanidi, 2019). It’s still far from certain that this is the case, and more studies are needed.

To be on the safe side, though, you should supplement with vitamin B12 only if you’ve been tested and found to have a deficiency. Take only the recommended amounts of B12.

Should you take vitamin B12 supplements?

If you have one or more risk factors for vitamin B12 deficiency or have symptoms of deficiency, speak with your healthcare provider. If you have a deficiency, your provider will suggest the type and amount of B12 supplementation you need. B12 supplements can interact with certain medications, including gastric acid inhibitors and metformin, so be sure to tell your provider if you take these or other medications (HHS, 2021).

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Ankar, A. & Kumar, A. (2021). Vitamin B12 deficiency. [Updated 2021 Jun 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct. 17, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441923/

Fanidi, A., Carreras-Torres, R., Larose, T. L., Yuan, J. M., Stevens, V. L., Weinstein, S. J., et al. (2019). Is high vitamin B12 status a cause of lung cancer? International Journal of Cancer , 145 (6), 1499–1503. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32033. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30499135/

Gille, D., & Schmid, A. (2015). Vitamin B12 in meat and dairy products. Nutrition Reviews , 73 (2), 106–115. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuu011. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26024497/

Langan, R. C., & Goodbred, A. J. (2017). Vitamin B12 deficiency: recognition and management. American Family Physician , 96 (6), 384–389. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28925645/

Linus Pauling Institute. (2021). Vitamin B12 . Oregon State University Micronutrient Information Center. Retrieved from https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/vitamins/vitamin-B12

Oliai Araghi, S., Kiefte-de Jong, J. C., van Dijk, S. C., Swart, K., van Laarhoven, H. W., van Schoor, N. M., et al. (2019). Folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: Long-term follow-up of the B vitamins for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures (B-PROOF) Trial. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology , 28 (2), 275–282. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30341095/

Oulhaj, A., Jernerén, F., Refsum, H., Smith, A. D., & de Jager, C. A. (2016). Omega-3 fatty acid status enhances the prevention of cognitive decline by B vitamins in mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease: JAD , 50 (2), 547–557. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150777. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4927899/

Sangle, P., Sandhu, O., Aftab, Z., Anthony, A. T., & Khan, S. (2020). Vitamin B12 supplementation: preventing onset and improving prognosis of depression. Cureus , 12 (10), e11169. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11169. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7688056/

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. (2019). Usual Nutrient Intake From Food and Beverages, by Gender and Age. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2013-2016 . Retrieved from https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/usual/Usual_Intake_gender_WWEIA_2013_2016.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). Vitamin B12 Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Retrieved on Oct. 17. 2021 from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Vitaminb12-HealthProfessional/