Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Depression can be debilitating—you may feel sad, unmotivated, and have difficulty enjoying the things you used to. Thankfully, there is help available, and SSRIs may be one tool on your path to recovery.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, are a class of antidepressant medications. In 1987, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first SSRI to treat depression—fluoxetine (brand name Prozac). Over the following decade, many other SSRIs came to market.

SSRIs dramatically changed the treatment of depression, offering healthcare providers and patients safer and more tolerable options compared to older antidepressants. In the 20 years following the approval of Prozac, antidepressant use in the United States increased by 400% (Hanrahan, 2014). While there are some warnings and side effects to consider, SSRIs provide many patients with an effective treatment option for depression and other mental health conditions.

How do SSRIs work?

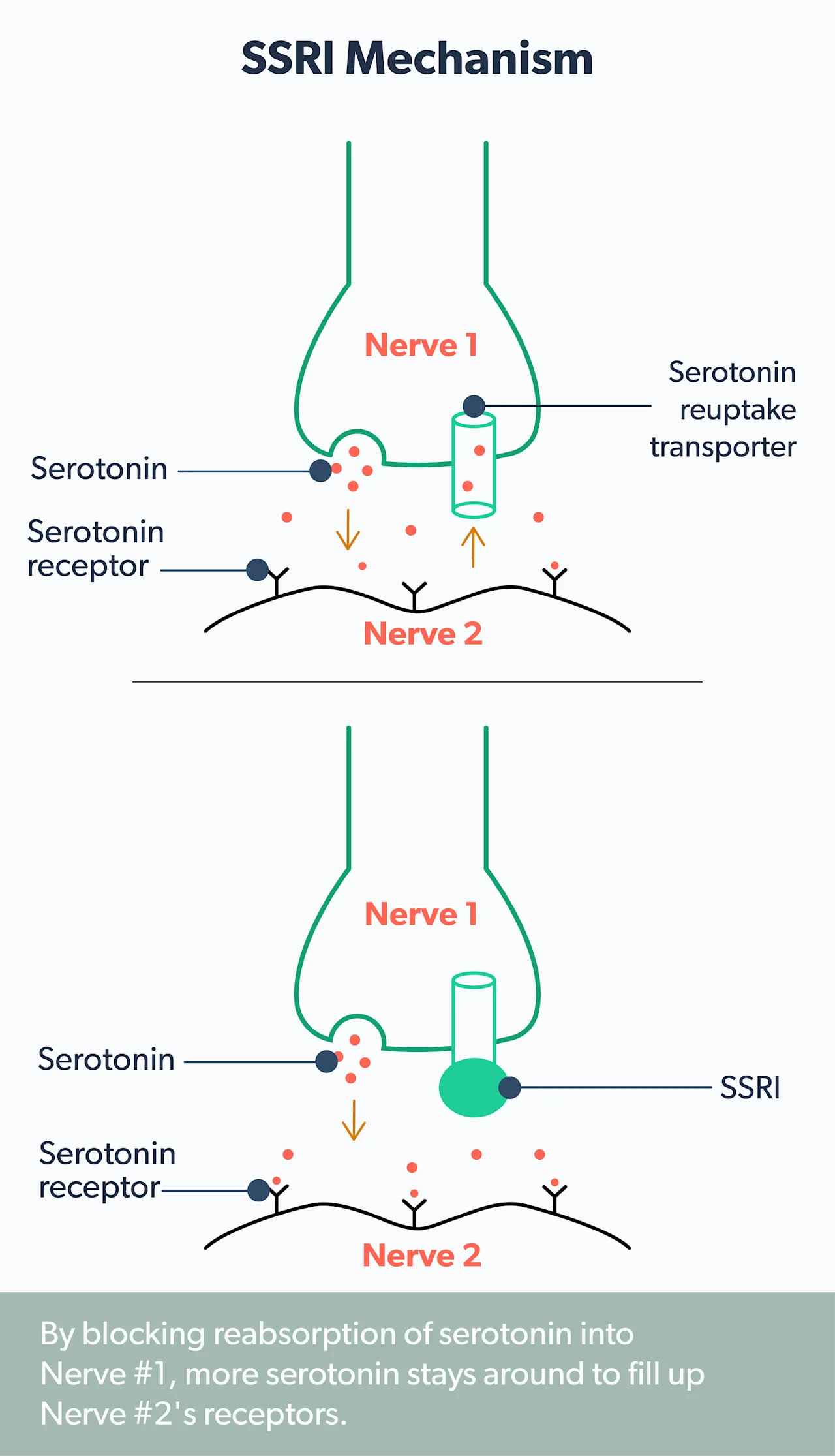

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter or chemical that sends a signal from one part of the body to another. In the brain, neurons (nerve cells) release serotonin, which helps regulate many processes involving mood, anger, fear, memory, sleep, appetite, and sexual behavior (Berger, 2009; Sahli, 2016).

Normally, once serotonin has done its job, it is taken back up into the cells and either broken down or stored for later use. SSRIs prevent the reuptake of serotonin into the cells, which increases levels of serotonin in the brain. Researchers believe that low levels of certain neurotransmitters, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, contribute to depression symptoms. SSRIs work to treat depression by restoring serotonin to healthy levels (Sahli, 2016).

When SSRIs are used to treat depression, there is typically a lag time before patients begin to see an improvement in their symptoms. For some, it may take six weeks or longer to achieve a full response (Sahli, 2016). Knowing this before you start treatment can help you manage your expectations and avoid getting discouraged if you don’t see results right away.

Use of SSRIs

SSRIs were originally developed to treat depression but have since proven useful for several other disorders. SSRIs are currently FDA-approved to treat the following conditions (depending on the specific medication):

Anxiety disorders (Pfizer, 2016)

Bipolar depression (Eli Lilly and Company, 2009)

Bulimia nervosa (Eli Lilly and Company, 2009)

Major depressive disorder (Pfizer, 2016)

Hot flashes and night sweats associated with menopause (GlaxoSmithKline, 2011)

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (Pfizer, 2016)

Panic disorder (Pfizer, 2016)

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Pfizer, 2016)

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (a severe form of premenstrual syndrome, or PMS) (Pfizer, 2016)

SSRIs can also be used “off-label” to treat other conditions, meaning the FDA didn’t explicitly approve them for those uses. Healthcare providers can prescribe drugs for an unapproved use if they decide that it’s the right treatment for their patients. Off-label uses for SSRIs include:

Body dysmorphic disorder (obsessing over perceived flaws in your physical appearance) (Phillipou, 2016)

Fibromyalgia (Patkar, 2007)

List of SSRIs

There are currently six FDA-approved SSRIs available in the United States:

Citalopram (brand name Celexa)

Escitalopram (brand name Lexapro)

Fluoxetine (brand name Prozac)

Fluvoxamine (brand name Luvox)

Paroxetine (brand names Paxil, Pexeva, Brisdelle)

Sertraline (brand name Zoloft)

Side effects of SSRIs

SSRIs are considered safer and better tolerated than older types of antidepressants (such as tricyclic antidepressants or TCAs); however, side effects can still occur. Side effects usually start within the first two weeks of treatment and can persist for months (Hu, 2004).

Common side effects to watch out for include (Eli Lilly and Company, 2009; Kostev, 2014):

Diarrhea

Difficulty sleeping

Dizziness

Dry mouth

Headache

Nausea

Nervousness

Rapid heart rate

Sexual dysfunction

Tiredness

Tremor

Weight gain (except fluoxetine which may cause weight loss)

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction is particularly bothersome, affecting 40–65% of both men and women who use SSRI antidepressants.

The most common sexual side effect is delayed ejaculation. (Healthcare providers actually take advantage of this side effect and often use SSRIs to treat patients with premature ejaculation). Other sexual effects include reduced sexual desire and satisfaction, inability to achieve orgasm, and erectile dysfunction (difficulty getting and maintaining an erection) (Jing, 2016).

All SSRIs have the potential to cause sexual problems, but paroxetine seems to be the worst offender. If you are experiencing sexual problems, your healthcare provider may suggest waiting a few weeks to see if sexual function improves. Other options include decreasing the dose, switching to a different antidepressant, or adding a medication to help with your symptoms (Jing, 2016).

If you experience any side effects from your SSRI, don’t hesitate to call your healthcare provider. Some SSRIs are more likely to cause certain side effects than others, so it may help to switch. Adjusting the dose to limit side effects may also be considered (Kostev, 2014).

Warnings and risks

If you’re starting an SSRI, there are several warnings to keep in mind. Here’s a look at some of the risks and steps you can take to help avoid them.

Suicide risk and antidepressants

The prescribing information for all antidepressant medications contains a boxed warning—the FDA’s strongest warning for severe and life-threatening risks—regarding the increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and young adults.

The warning states that healthcare providers and family members should monitor patients for any signs of worsening mood when starting an antidepressant. Studies did not show an increased risk in adults over the age of 24, and the risk was decreased in adults 65 years and older (Friedman, 2014).

Untreated depression can also increase suicidal thoughts and behaviors. You and your healthcare provider must balance these risks when considering whether or not to start treatment.

Serotonin syndrome

Serotonin syndrome occurs when there is too much serotonin in the brain. SSRIs may cause serotonin syndrome on their own, especially if you take too much. However, it more commonly occurs when a patient takes two or more medications that increase serotonin (Foong, 2018).

Symptoms of serotonin syndrome can range from mild to life-threatening. Mild symptoms include diarrhea, nervousness, and tremor. As the syndrome progresses, patients can experience sweating, agitation, and muscle spasms. If the condition becomes severe, fever, muscle stiffness and breakdown, and confusion can occur. If you suspect you are experiencing signs of serotonin syndrome, it is important to seek medical care urgently (Foong, 2018).

Certain medications increase the risk of developing serotonin syndrome and should not be taken with SSRIs (Foong, 2018):

A class of drugs called monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are particularly risky when taken with SSRIs and must be avoided. These include certain antidepressants and medications used to treat Parkinson’s disease.

Drugs of abuse, such as MDMA, or ecstasy, can also increase your risk.

Many other medications can interact with SSRIs, so be sure to talk to your healthcare provider before starting anything new so they can check for drug interactions.

Cardiac risks

Rarely, SSRIs, particularly citalopram, can disrupt the normal electrical activity in your heart and lead to arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms). The risk of this side effect increases with higher doses. As a result, the FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication in 2011 recommending lower dosing guidelines for citalopram. Even with lower doses, the potential for arrhythmias still exists. Your healthcare provider may recommend additional monitoring if you have underlying risk factors or are taking other medications that affect the heart’s electrical activity (FDA, 2017).

Bleeding risks

SSRIs may increase the risk of bleeding, including bleeding in the stomach. The risk appears to be greater if you also take NSAID medications, such as aspirin, ibuprofen, or naproxen, or blood thinners (Yuet, 2019). Be sure to let your healthcare provider know about all medications you take, including over-the-counter products.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding considerations

SSRIs are the most common type of antidepressants prescribed to pregnant people. Some studies have shown a small increase in the risk of birth defects when SSRIs were used during pregnancy. However, it is difficult to know if the SSRIs directly caused these outcomes. Babies exposed to SSRIs during pregnancy can be irritable and have trouble feeding or sleeping shortly after birth. These effects may last for several days (Wichman, 2015).

The potential risks of SSRIs must be weighed against leaving depression untreated and the negative impact that can have on your pregnancy. Your healthcare provider will help you understand your options and determine the best course of treatment for your situation.

If you wish to breastfeed your baby, there’s no need to stop your SSRI. Healthcare providers generally consider SSRIs safe during breastfeeding; however, some babies may experience drowsiness or fussiness (Fluoxetine, 2021). Two SSRIs, sertraline (brand name Zoloft) and paroxetine (brand name Paxil), are found in low concentrations in breast milk and may be preferred over the other SSRIs (Paroxetine, 2021; Sertraline, 2021).

Discontinuation syndrome

Stopping your SSRI can cause some withdrawal symptoms to occur, especially if you stop taking it suddenly, without slowly decreasing the dose. Not everyone who stops an SSRI will experience symptoms. Those that do will often have mild symptoms, including dizziness, tiredness, nausea, and headache. Others can experience more bothersome effects such as anxiety, agitation, trouble sleeping, body aches, chills, sweating, and a burning or tingling sensation. Most people will start to feel better within 2–3 weeks, but it can take longer (Jha, 2018).

Always talk to your healthcare provider before stopping any of your medications. Together, you can develop a plan to reduce your dose slowly and minimize any adverse effects that can occur.

If you’re suffering from depression, SSRIs may be an option to include in your treatment plan. Talk with your healthcare provider about your symptoms and concerns. Together, you can come up with a plan to get you started on the road to recovery.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Berger, M., Gray, J. A., & Roth, B. L. (2009). The expanded biology of serotonin. Annual Review of Medicine, 60 , 355–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.042307.110802. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19630576/

Brownley, K. A., Berkman, N. D., Peat, C. M., Lohr, K. N., Cullen, K. E., Bann, C. M., & Bulik, C. M. (2016). Binge-eating disorder in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165 (6), 409–420. doi: 10.7326/M15-2455. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27367316/

Eli Lilly and Company. (2009). Prozac: Highlights of prescribing information. Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/018936s075s077lbl.pdf

Fluoxetine. (2021). In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Library of Medicine (US). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30000245/

Foong, A. L., Patel, T., Kellar, J., & Grindrod, K. A. (2018). The scoop on serotonin syndrome. Canadian Pharmacists Journal : CPJ = Revue des pharmaciens du Canada : RPC, 151 (4), 233–239. doi: 10.1177/1715163518779096. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6141939/

Friedman, R. A. (2014). Antidepressants' black-box warning--10 years later. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371 (18), 1666–1668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1408480. Retrieved from https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp1408480

GlaxoSmithKline. (2011). Paxil (paroxetine hydrochloride) tablets and oral suspension. Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/020031s067%2C020710s031.pdf

Hanrahan, C., & New, J. P. (2014). Antidepressant medications: The FDA-approval process and the need for updates. Mental Health Clinician, 4 (1), 11-16. doi: 10.9740/mhc.n186950. Retrieved from https://meridian.allenpress.com/mhc/article/4/1/11/37061/Antidepressant-medications-The-FDA-approval

Hu, X. H., Bull, S. A., Hunkeler, E. M., Ming, E., Lee, J. Y., Fireman, B., & Markson, L. E. (2004). Incidence and duration of side effects and those rated as bothersome with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment for depression: patient report versus physician estimate. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65 (7), 959–965. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0712. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15291685/

Jha, M. K., Rush, A. J., & Trivedi, M. H. (2018). When discontinuing SSRI antidepressants is a challenge: management tips. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175 (12), 1176–1184. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18060692. Retrieved from https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18060692

Jing, E. & Straw-Wilson, K. (2016). Sexual dysfunction in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and potential solutions: a narrative literature review. The Mental Health Clinician, 6 (4), 191–196. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.07.191. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29955469/

Kostev, K., Rex, J., Eith, T., & Heilmaier, C. (2014). Which adverse effects influence the dropout rate in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment? Results for 50,824 patients. German Medical Science: GMS e-journal, 12 , Doc15. doi: 10.3205/000200. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25332703/

McMahon, C. G. & Porst, H. (2011). Oral agents for the treatment of premature ejaculation: review of efficacy and safety in the context of the recent International Society for Sexual Medicine criteria for lifelong premature ejaculation. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8 (10), 2707–2725. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02386.x. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21771283/

Paroxetine. (2021). In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Library of Medicine (US). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30000249/

Patkar, A. A., Masand, P. S., Krulewicz, S., Mannelli, P., Peindl, K., Beebe, K. L., & Jiang, W. (2007). A randomized, controlled, trial of controlled release paroxetine in fibromyalgia. The American Journal of Medicine, 120 (5), 448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.006. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17466657/

Pfizer. (2016). Zoloft: Highlights of prescribing information. Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/019839S74S86S87_20990S35S44S45lbl.pdf

Phillipou, A., Rossell, S. L., Wilding, H. E., & Castle, D. J. (2016). Randomised controlled trials of psychological & pharmacological treatments for body dysmorphic disorder: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research, 245 , 179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.05.062. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27544783/

Sahli, Z. T., Banerjee, P., & Tarazi, F. I. (2016). The preclinical and clinical effects of vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery, 11 (5), 515–523. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2016.1160051. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26971593/

Sertraline. (2021). In Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). National Library of Medicine (US). Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30000250/

U.S Food & Drug Administration (FDA). (2017, December). FDA Drug Safety Communication: Revised recommendations for Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) related to a potential risk of abnormal heart rhythms with high doses. Retrieved May 10, 2021, from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-revised-recommendations-celexa-citalopram-hydrobromide-related

Wichman, C. L. & Stern, T. A. (2015). Diagnosing and treating depression during pregnancy. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 17 (2), 10.4088/PCC.15f01776. doi: 10.4088/PCC.15f01776. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4560196/

Yuet, W. C., Derasari, D., Sivoravong, J., Mason, D., & Jann, M. (2019). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and risk of gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 119 (2), 102–111. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2019.016. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30688347/