Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

The relationship between weight, fertility, and pregnancy is a sensitive and complicated one. Weight stigma (assumptions and/or mistreatment based on someone's weight) is a very real experience for many people — and there's reason to believe that could actually contribute to healthcare outcomes.

So, how can you make sure the care you're receiving is based on your individual health and not solely based on trends in population data? How can you find a provider who also understands the potential effects of weight stigma? We've pulled together this article to help you better navigate preconception, fertility, and prenatal healthcare — and make the right decisions for your own healthcare journey.

The biggest takeaways

People get pregnant and have healthy pregnancies at all sizes. But research has associated some adverse outcomes with different body-fat percentages.

Conversations about weight will often be a part of the experience in preconception, fertility, and prenatal care. Healthcare providers use large-scale data to inform care plans and reduce the likelihood of adverse outcomes.

There are providers who have a more nuanced take on weight, fertility, and pregnancy. Know that you can seek out these providers or tell an existing provider what will make you feel the most comfortable in their care.

First things first: What's BMI again?

In healthcare settings and clinical research, body mass index (aka BMI) comes up a lot. BMI is a way to measure weight relative to height and predict body-fat percentage. Though BMI measurements are flawed (more on this in a bit), healthcare providers often use them as a way to tailor care and guidance — and researchers use them to try to make sense of health risks seen in large populations. Why? Research demonstrates that body-fat percentage may play a role in health outcomes, and BMI is an easy method for estimating that percentage: You just need to divide a person's weight in kilograms (kg) by their height in meters squared (kg/m^2).

"In obstetrics in particular, we rely heavily on BMI as a predictor of health because of its prevalence in the clinical research that guides our practice in medicine,” says Dr. Jenn Conti, MD, MS, MSc, OB-GYN and Modern Fertility medical advisor. “The problem is that we don’t yet have a better standardized measure of how body size affects outcomes, so medical recommendations continue to prioritize BMI even though we know it’s imperfect.”

There are general guidelines around BMI categories for adults:

Under 18.5: "Underweight"

18.5-24.9: "Normal"

25-29.0: "Overweight"

Over 30: "Obese"

So, why is BMI a flawed measurement tool? Two main reasons: where the original information came from, and how little it truly assesses overall health.

A little BMI history

The formula that underpins BMI was created by a 19th-century mathematician, Adolphe Quetelet, who collected data to understand the characteristics of the so-called "average man" and see how prevalent these characteristics were at the population level. He used this data, primarily from European people who produce sperm, to develop "average" height-to-weight ratios.

As researchers and insurance companies were trying to connect the dots between body-fat percentage and health in the 20th century, they needed a way to easily capture body-fat percentage across large populations. In the '70s, Quetelet's formula was revived as the best option and repackaged as BMI. (Although the Quetelet data was replaced with newer data, researchers continued to mostly pull it from white people with sperm.)

The TL;DR here is that a formula designed by a mathematician evolved into the same formula the healthcare system uses today to evaluate patients — and sometimes even qualify them for fertility treatment and other procedures.

What BMI can (and can't) tell us

Aside from BMI's history, the measurement tool doesn't always work as an accurate predictor of body-fat percentage or overall health:

BMI can't distinguish between fat and muscle, so people with high muscle mass (which weighs more than fat) might be incorrectly categorized. (This is a huge issue among athletes.)

BMI also can't tell the difference between various kinds of fat or how fat is distributed in the body, all of which plays a role in potential high impact.

BMI doesn't take the many other health-related factors into consideration: People with higher BMI can have "normal" health markers and people with lower BMI can have "abnormal" health markers.

Despite all this, BMI remains a fixture in healthcare settings and health research because of its ease of use. BMI's prevalence is why the research we're including in the next section all centers around BMI rather than weight.

So, what does the research say about weight, fertility, and pregnancy?

We'll get into the studies in a minute, but there are a few disclaimers we'd like to cover first:

1. Weight isn't 100% in our control. While we can change our approaches to nutrition and exercise, weight isn't only impacted by lifestyle choices. There's solid evidence that weight is at least in part genetic. This means we're likely predisposed to certain weight ranges.

2. Health conditions can contribute to weight. Weight changes are a common feature of thyroid conditions — and weight gain in particular (as well as insulin resistance, which can affect fertility) is often associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). (If unexpected weight changes happen, it's a good idea to reach out to your healthcare provider to see if an underlying health condition could be the cause.)

3. Population data shows correlation, not causation. Large-scale population data doesn't necessarily demonstrate cause and effect. What population data can do is show us that there's a potential relationship between two factors. The data tells a story connecting weight and fertility, but there might be missing context. For example, psychosocial factors (like stress or weight stigma) aren't always accounted for in research on weight, fertility, and pregnancy.

4. Everyone's experiences are unique. Doctors use aggregate data like what we're including here to understand what risks to look out for in certain populations and take steps to prevent them. But just because there's a potential correlation reflected in the data doesn't mean you will definitely have an adverse outcome. (Age-related chances of conception are also a good example of this.)

"Preconception is generally a time when people are trying their hardest to optimize health in preparation for a pregnancy,” adds Dr. Conti. “If the metrics and messaging we use stigmatize rather than empower people to continue positive health behaviors, then what are we really accomplishing? I always try to put this in context for people, reminding them that 1) there are absolutely improvements we can make in our health habits, and 2) we can only do our best.”

(Two positive health habits that are recommended for everyone, especially in the preconception stage? Balanced nutrition and regular physical activity.)

Now that we've gotten those caveats out of the way, let's see what the science says about weight, fertility, and pregnancy.

Body-fat percentage and menstrual cycles

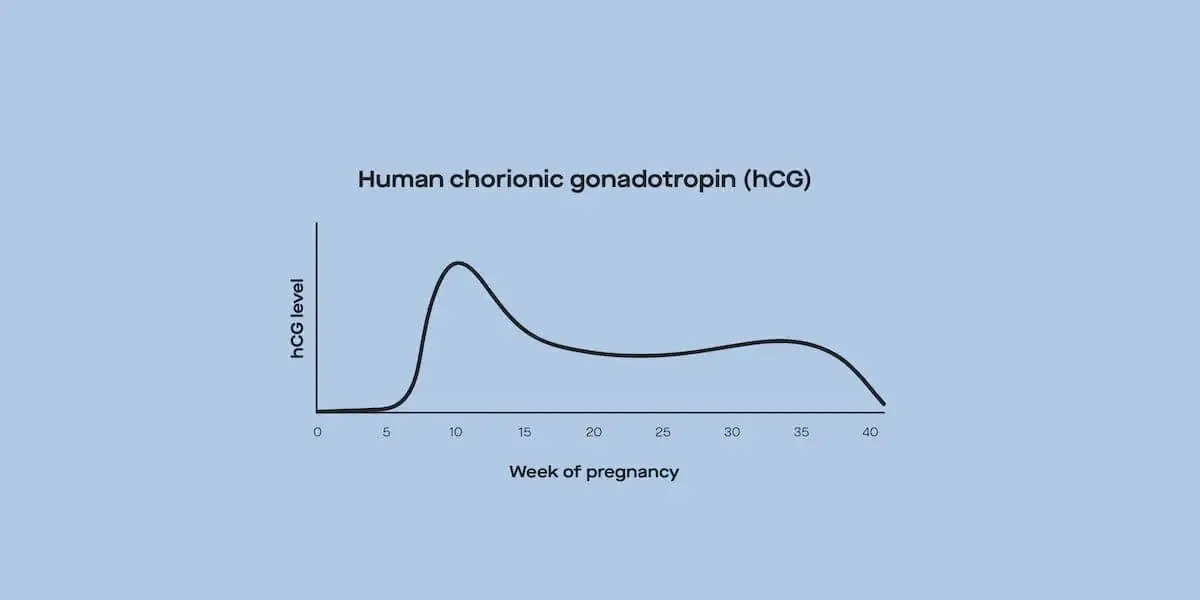

The conception puzzle has many pieces — one of which is a regular menstrual cycle. Reproductive hormones (like the estrogen estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone) keep your menstrual cycle moving from egg maturation through ovulation through your period and back again. In order to get pregnant, an egg must be released (ovulation) through the fallopian tube so it has a chance to meet up with sperm.

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) writes that people with low and high BMIs may have irregular menstrual cycles or cycles without ovulation. (Most of the reasons boil down to under- or overproduction of hormones and disruption of the typical hormonal sequence guiding menstrual cycles.) Irregular ovulation makes it more challenging to time sex or insemination around your most fertile days — and without any ovulation at all, no egg will be available for fertilization. In these situations, changes in nutrition and exercise, as well as ovulation-inducing medications (like clomiphene citrate aka Clomid or letrozole aka Femara), can help.

Body-fat percentage and time to pregnancy

An often-cited study from 2004 that included 2,112 pregnant women between the years of 2000 and 2001 had these findings:

Women with BMIs under 19 took 29 months to conceive.

Women with BMIs between 19 and 24 took 6.8 months to conceive.

Women with BMIs between 25 and 39 took 10.6 months to conceive.

Women with BMIs above 39 took 13.3 months to conceive.

The study had the same findings after accounting for other lifestyle variables (like smoking, caffeine and alcohol intake), menstrual cycle regularity, and age.

How does this data compare to the "average" chances of conception per cycle? A 2017 study with almost 3,000 opposite-sex couples in the US found that, on average, 58% of their participants conceived after six months and 75% after 12.

Body-fat percentage and fertility treatment outcomes

Let's break this down into fertility treatment types:

Intrauterine insemination (IUI): One 2011 retrospective study with 477 women who took ovulation-inducing medication before undergoing 1,189 intrauterine insemination (IUI) cycles concluded that while people with BMIs categorized as "obese" may need increased doses of medications but ultimately had the same outcomes when medication was adjusted for individual weight.

In vitro fertilization (IVF): A 2016 retrospective cohort study that examined all US data (494,097 cycles) on in vitro fertilization (IVF) outcomes from 2008 to 2013 that was reported to the CDC's National Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Surveillance System found that people with BMIs in the "underweight" and "obese" categories had decreased rates of pregnancy and live birth per embryo transfer.

Body-fat percentage and pregnancy

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a 2019 Committee Opinion stating that low BMI was associated with higher rates of having small-for-gestational-age and low-birth-weight infants — and high BMI was associated with higher rates of miscarriage, preterm delivery, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, caesarean-section (C-section), blood clots, birth defects, and even stillbirth.

Here's what the science says:

A 2021 study analyzed the pregnancy outcomes of 669,101 people and found that people with low BMI had increased risks of preterm birth. High body-fat percentage increased the risk of C-section delivery, stillbirth, and preterm birth. But the researchers noted that more investigation is needed to understand exactly why — and to figure out whether or not weight-related counseling would be helpful.

A 2020 ACOG consensus article on stillbirth notes that while body-fat percentage in the category of "obesity" remains an independent risk factor for stillbirth after controlling for smoking, gestational diabetes, and preeclampsia, the "optimal" BMI to minimize stillbirth risk remains unknown. This association is likely multifactorial — but primarily resulting from dysfunction at the level of the placenta.

A meta-analysis from 2019 evaluated 46 studies (the only ones that met their criteria out of 2,454) and confirmed some of ACOG's Committee Opinion, as well as concluded that high BMI increased the risk of "fetal overgrowth," premature birth, and neonatal asphyxia (a lack of oxygen and blood flow to the fetal brain).

Do some people have to lose or gain weight before trying to get pregnant?

We're not here to tell you what to do or what not to do: Deciding to make changes you think might improve fertility and pregnancy outcomes is between you and your healthcare provider. What we are here to do is help you understand the conversations you can expect around weight throughout preconception, fertility, and prenatal care.

Weight and preconception appointments

Let's first talk about low body-fat percentage and fertility in particular. When someone with a low body-fat percentage doesn't get periods (a side effect that's been associated with all forms of eating disorders), a higher body-fat percentage is one of the most necessary factors for recovery of "normal" menstrual cycles. In these cases, the body will need to adjust the ratio of energy input and output to see the return of ovulation. But this isn't easy for everyone — some people may need the support of their healthcare provider, a therapist, and a dietitian to make significant changes to their relationship with eating and exercise.

As for losing weight to improve fertility outcomes, we have research specifically around populations with infertility to look to: A 2017 meta-analysis concluded that for people with higher body-fat percentage and fertility issues, losing a percentage of that body fat through nutrition and exercise changes may have a positive effect on chances of pregnancy.

Based on data like this, healthcare providers may recommend weight gain or loss for people with fertility issues and BMIs outside the "average" range. Clinical guidelines (which are fueled by data) also support proactively counseling on weight in preconception appointments.

“Weight often comes up naturally in preconception visits with my patients. We talk about all aspects of a person’s health that can be optimized to improve fertility and pregnancy outcomes based on what data we have," explains Dr. Conti. "Sometimes that’s connecting with a therapist to address mental health concerns, getting up to date on vaccinations, or increasing activity level — and it’s important to contextualize weight as just another aspect of optimization rather than something someone has failed at/should be shamed for.”

Weight and fertility clinic appointments

Many fertility clinics have upper BMI cutoffs before starting fertility treatment — which means weight-loss interventions may need to take place before the clinic even agrees to treat someone. Some researchers argue that these cutoffs aren't supported by evidence and contribute to weight stigma in fertility care. (They also note that age likely plays a larger role than body-fat percentage in certain outcomes.)

What does the evidence show? One randomized controlled trial (aka RCT, which is the gold-standard in clinical research) from 2016 compared the effectiveness of immediately starting fertility treatment against a six-month "lifestyle intervention" (changes in nutrition and exercise to lose 5%-10% body weight) before treatment in improving outcomes. For people with higher BMIs who were experiencing issues with fertility, the intervention did not lead to higher rates of healthy vaginal births or reduce the rates of complications.

Weight and prenatal care appointments

Research linking weight and adverse pregnancy outcomes often shapes prenatal care. Providers may categorize pregnancies as "high-risk" based on weight — which could mean additional appointments and specialists in the mix.

Weight and delivery

When pregnancies are considered "high-risk" because of weight, birth plans can be affected. In some cases, increased medical support may be recommended — like giving birth in a hospital (versus at home) and working with an OB-GYN (versus a midwife). That said, you can always talk to your provider about what you're comfortable with and how you might uniquely be impacted by childbirth to land on a plan that works for you.

What can you do if you'd prefer a more weight-neutral, individualized approach to care?

If you'd feel more supported by a care team that's especially sensitive around weight and mindful of the stigma surrounding body size, here are some steps you can take:

1. Seek out Health At Every Size (HAES) healthcare professionals: Health At Every Size (HAES) is a movement that celebrates and values body differences, challenges assumptions about size, and promotes a compassionate, individualized approach to exercise and nutrition. You can find HAES-aligned practitioners in their online registry. (Heads-up: The registry is, unfortunately, a little light on OB-GYNs and other medical doctors — but we're hoping to see more here soon.)

2. Understand how different fertility clinics approach weight: You can also read through fertility clinic reviews (or even call them up!) to get a sense of how their fertility specialists treat patients of all sizes. UK-based fertility coach Nicola Salmon rounds them up right here. Also be sure to investigate if clinics have BMI cutoffs for treatment so you know what to expect.

3. Ask for what you need: Whether or not you're working with a provider who's mindful of weight stigma and its impact, you can always ask for what you need to have a more positive healthcare experience. If you feel comfortable, you can explain to your provider that you'd like to be treated holistically — beyond your BMI or a number on a scale. Although weigh-ins will be a regular part of all prenatal care, you can also request not to see your weight if that's something that could be triggering in any way.

For anyone who's experienced weight stigma or wants to explore their own relationship with weight inside or outside women's health, our Modern Community staff therapist, Meghan Cassidy, LCSW-C, recommends considering therapy as a way to unpack those complex emotions. Meghan is specifically a major proponent of finding an expert in somatic experiencing, a form of trauma therapy that helps people, as she explains it, "explore and heal from hard emotions and trauma by releasing emotions from where we hold them in our bodies."

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.