Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

With the rapid adoption of GLP-1 receptor agonist or GLP-1/GIP medications (hereafter, GLP-1 medications) as weight loss interventions, there has been a groundswell of interest in this class of pharmacotherapy. One area that has attracted academic discussion, press coverage, and significant biotechnology/pharma R&D investment is concern about undesirable, collateral skeletal muscle mass (SMM) loss, and presumably by extension, loss of strength and function in people taking GLP-1 medications. This is a worthwhile topic of focus as body composition following weight loss (especially muscle mass) may impact overall quality of life.

However, a needed framing of this question is not whether GLP-1 medications induce SMM loss at all, but rather does greater SMM loss occur as compared to the normal degree of SMM loss that occurs with other weight loss interventions?

This is akin, for example, to the oft-discussed purported “Ozempic face” where the shape of the face may change following weight loss. Yet, as others have noted, there is not compelling evidence that this is specific to Ozempic, but rather is presumed to be a normative consequence of weight loss regardless of the method (Peters et al., Tanikawa et al.).

Answering this question will require new data and analyses adhering to sound scientific practices including:

Defining the question

Defining the outcome variables

Using inferentially strong research designs

Using sound and relevant outcome measurements

Using valid statistical analyses

Summarizing the totality of evidence

We have defined the question, and in today’s post, we’ll review the current state of evidence. In subsequent publications, we will more deeply examine and present the definitions of SMM and strength and function, methodological gaps, and research needed to bring robust evidence to the topic.

Why is this question important

Taking a step back, conceptually, we expect persons who lose weight, irrespective of the mechanism, to lose both fat mass (FM) and fat free mass (FFM) (persons with obesity generally have higher baseline levels of FFM and SMM than do persons without obesity). Still, this topic has garnered much attention. The media (e.g., New York Times, Good Morning America), food and nutrition brands (e.g., Nestle), and medical providers have focused on the potential for SMM loss among persons treated with GLP-1 medications.

Additionally, biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies are examining how to repurpose molecules implicated in skeletal muscle pathways (such as myostatin/activin, apelin, and mTOR), and developing new molecules and medications to maintain SMM while benefiting from GLP-1 medications' positive health effects. As such, the answer to this question pertains to everything from a patient’s decision to use a GLP-1 medication or a provider’s likelihood of prescribing one, to health plans’ and employers’ coverage decisions, and investment strategies for companies ranging from consumer products to pharma.

What does the evidence currently show

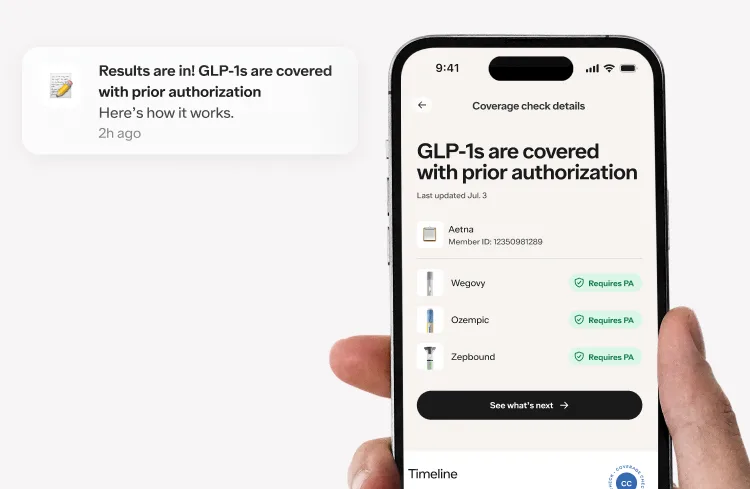

Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analysis of RCTs show that semaglutide and tirzepatide (two types of GLP-1 medications) reduce body weight, waist circumference, and improve major cardiometabolic risk biomarkers (e.g. blood pressure, blood sugar, and lipid profile).

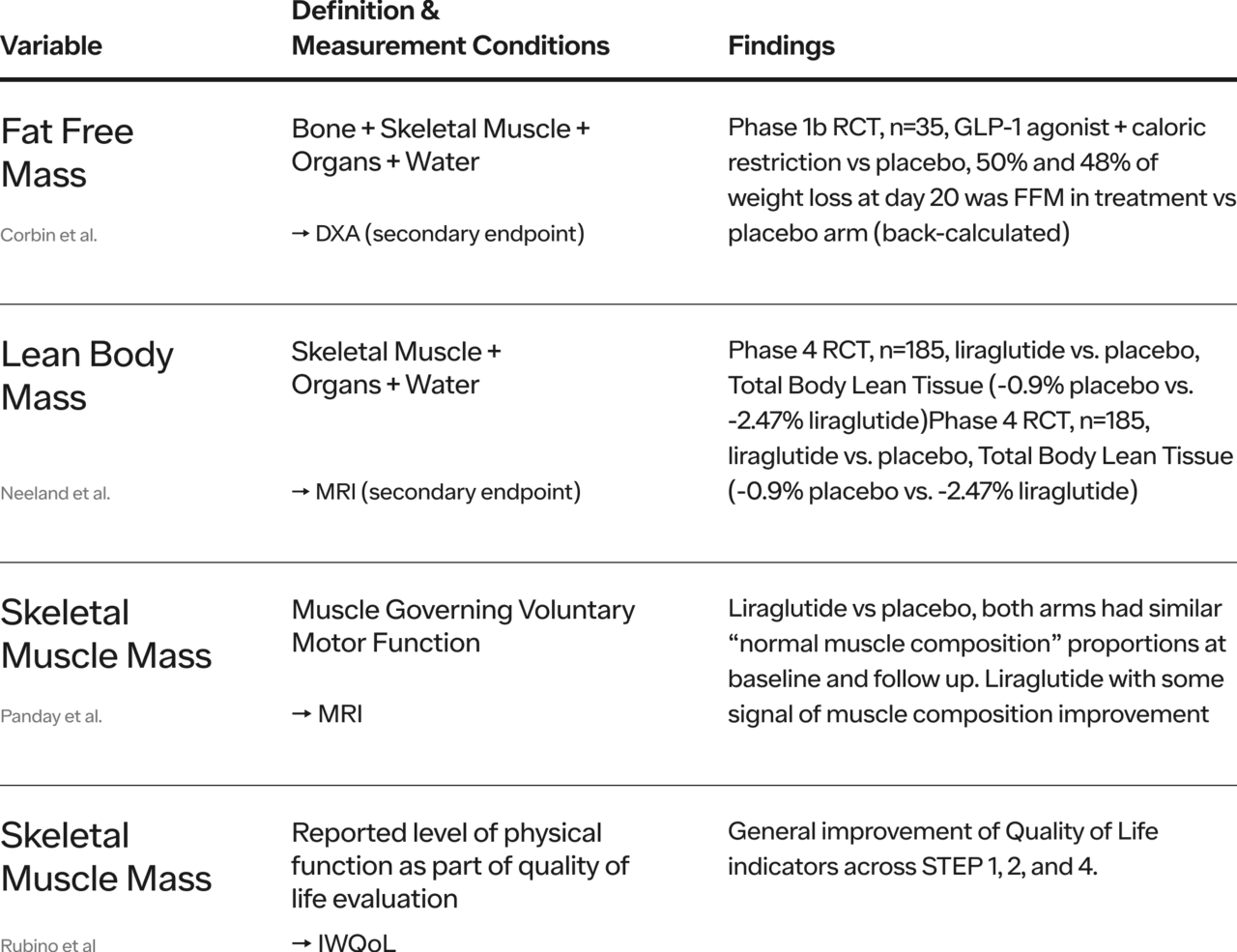

Regarding GLP-1 medications and the question of purported SMM loss, there is a paucity of published human RCT data explicitly and thoroughly addressing the question with valid probative methods. Ideally, one would compare body composition outcomes (including direct measurements of SMM), strength, and function (performance) in persons losing weight with GLP-1 medications in a ‘head-to-head’ fashion with non-GLP-1 medications. It is also worth noting there is not a 1:1 correspondence between resistance training, SMM and strength and indeed some research suggests that many clinical interventions may improve strength without appreciable effects on SMM by strengthening the neuromuscular junction and quality of muscle (Nuzzo, J., Schoenfeld, B., Loenneke, J.).

Note: see Appendix for an abbreviated summary of strikingly limited head-to-head RCT evidence that exist at the time of this writing

Matiegka defines FFM as bone + skeletal muscle + connective tissue + organs + water. Some authors use FFM interchangeably with Lean Body Mass (LBM). However, LBM is defined as skeletal muscle mass + connective tissue + organs + water which is not the same thing as FFM.

There are several ways to measure or estimate SMM (e.g. bioelectric impedance, computed tomography or CT, magnetic resonance imaging or MRI, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry or DXA, D3-creatine dilution), the choice of these methods depends on purpose of measurement (e.g. clinical monitoring vs scientific hypothesis testing), precision and validity needed, cost, convenience, reproducibility, and speed of data acquisition. As of this writing (July 2024), we are not aware of robust head-to-head RCTs comparing GLP-1 medications outcomes to outcomes with other forms of weight loss intervention on validly-measured SMM, strength, or function. This remains a vital research need.

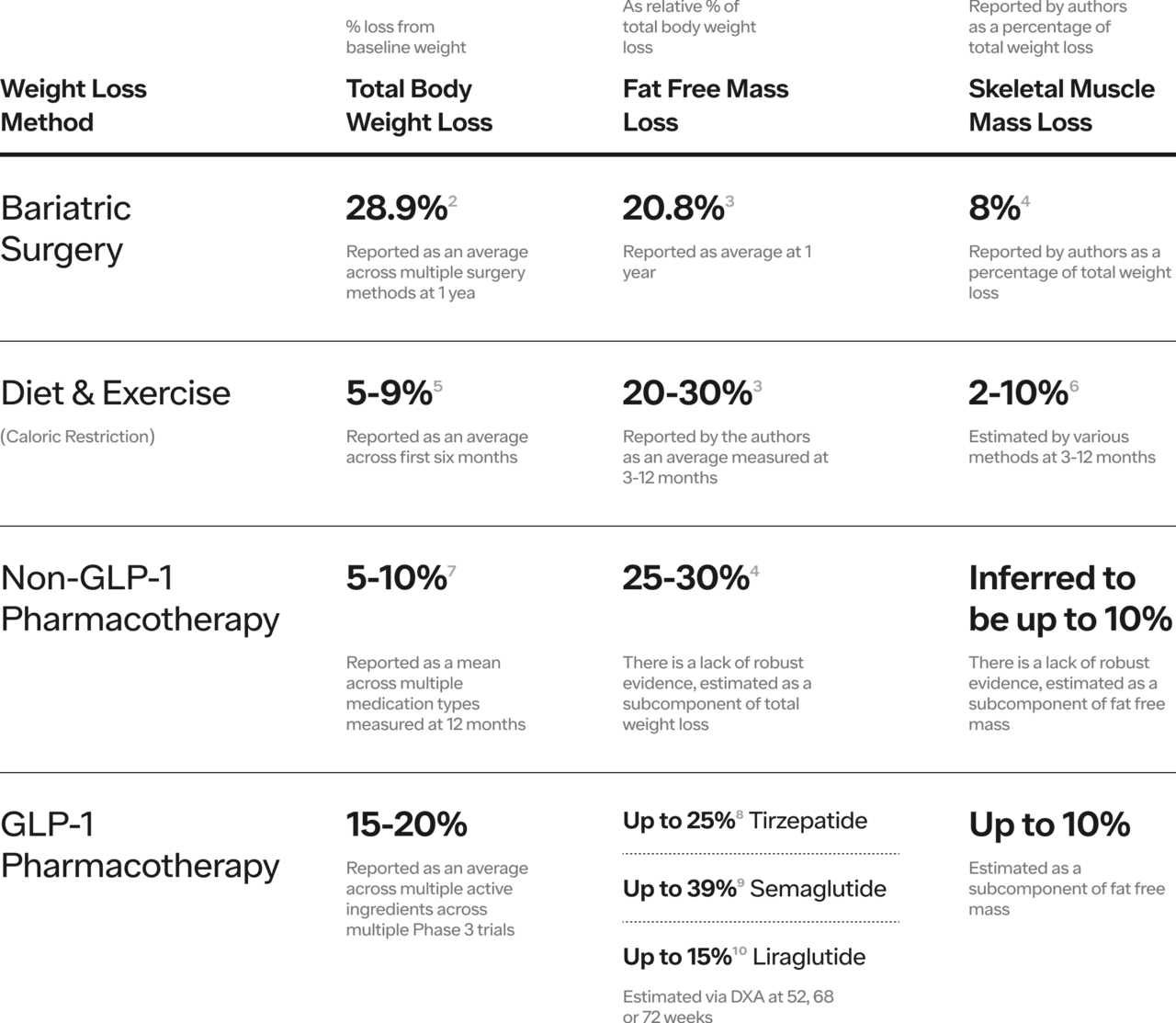

Temporarily putting aside the desire for head-to-head RCTs, systematic reviews of clinical trial data (both Phase 3 registration trials and smaller studies), describe FFM loss relative to total weight loss. The evidence supports two general conclusions: 1) approximately one quarter of weight loss will be FFM 2) SMM accounts for approximately 50% of FFM (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Range of Total Body Weight Loss, Fat Free Mass Loss and Skeletal Muscle Mass Loss by Weight Loss Method.

In the STEP 1 trial which studied semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity, researchers studied body mass composition as a secondary endpoint via DXA in a subpopulation of trial enrollees randomized to treatment or placebo. On average, FM loss comprised 55% of total weight lost whereas LBM comprised ~35%. These authors concluded that “the proportion of LBM relative to total body mass increased with semaglutide.” Similarly, in the SURMOUNT-1 trial which studied tirzepatide, researchers found that “participants treated with tirzepatide had a percent reduction in fat mass approximately 3 times greater than the reduction in lean mass, resulting in an overall improvement in body composition.” More recently, a viewpoint in JAMA re-grounded the conversation: weight loss in persons with obesity primarily reduces body fat, but also decreases fat free mass (FFM). If we recall that approximately 25% of total weight loss in persons with obesity is accounted for by FFM, the authors found that fat free mass accounted for 33%, 39%, and 25% of total weight loss for retatrutide (Phase 2 data only, not yet FDA approved), semaglutide and tirzepatide respectively whereas fat mass loss accounted for 67%, 61%, and 75% respectively. Stated differently, FM loss occurred at a rate 2-3x higher than FFM loss.

What can we conclude

To date, we have not seen robust reports that persons with obesity or overweight taking GLP-1 medications experience greater SMM loss than persons with obesity or overweight taking non-GLP-1 medications (after controlling for greater total weight loss). In fact, the ratio of FFM to FM has been observed to increase on GLP-1 medications plausibly more than non-GLP-1 medications (by as much as 2-3x, which has been corroborated in large Phase 3 clinical trials across multiple active compounds).

In summary:

Evaluating SMM loss plausibly due to GLP-1 medications compared to weight loss through other interventions (without GLP-1 medications), we find a dearth of evidence of disproportionate muscle mass loss.

There is evidence that suggests GLP-1 medications may lead to improved body composition as the loss of fat mass is often 2-3x greater than the loss of fat free mass.

One study, using objective instruments to measure some aspects of physical function, reported that GLP-1 medications significantly improved physical function compared to placebo.

As evidence accrues, we, and others, will monitor what it means for the impact of GLP-1 medications on SMM, but so far we have not seen any compelling clinical data (although new systematic reviews and meta analyses have been proposed) that GLP-1 medications lead to pathological skeletal muscle mass loss relative to what has been demonstrated and observed in other weight loss interventions. In fact, we see some evidence that suggests but does not yet prove that both body composition and physical function improve significantly following GLP-1 medication intervention. As physical well-being improves following weight loss, additional functional outcomes (e.g. grip strength, activities of daily living score, SF-36, sit to stand) merit further study as well.

In subsequent publications, we will review:

What are fundamental definitions of fat mass vs fat free mass vs lean body mass?

What are the methods available to measure fat mass vs muscle mass?

What are study designs and measurement tools and outcomes necessary to answer the question posed in this article?

†Dr. Allison is a distinguished professor and dean at Indiana University-Bloomington and is acting as an independent consultant to Ro and his views do not necessarily represent those of Indiana University-Bloomington or any other organization

1,2,3,4Drs. Manalac, Broffman, Chai and Nicholas Samonas are full time employees of Ro

*We recognize the editorial contributions of: Nicholas Samonas3, Sam Chai PhD4

Appendix

As of this writing, there are few randomized, placebo controlled studies looking at head to head comparisons between GLP-1 medications and non GLP-1 medications with robust body anthropometry (composition) methods. We have listed studies below that begin to answer this question.

References

GLP-1 medications here refers to medications built on a GLP-1 backbone, but could also mean GLP-1 based medications that target glucagon receptor (GCGR) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR)

Bariatric Surgery Worldwide: Baseline Demographic Description and One-Year Outcomes from the Fourth IFSO Global Registry Report 2018.

The magnitude and progress of lean body mass, fat‐free mass, and skeletal muscle mass loss following bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta‐analysis - PMC

Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss

a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up

Preserving Healthy Muscle during Weight Loss - PMC

Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Anti-Obesity Treatment: Where Do We Stand?

Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity | New England Journal of Medicine

https://dom-pubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dom.15728

https://dom-pubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dom.15728

Note: the FDA considers body composition metrics to be safety endpoints which often results in underpowered secondary endpoints in Phase 3 registration trials