Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

There has been a lot of debate on the merit and cost of GLP1s. I’m here to tell you that their dominance is inevitable and why. I’m also going to explain why every day we don’t solve for the cost and coverage of these drugs, we risk the greatest acceleration of health inequity of our lifetime–creating an even greater gap in health equity that I believe will have a profound and durable impact on our society that will be increasingly difficult to reverse. At the same time, I believe GLP1s (and adjacent drugs) also present the greatest opportunity to bridge the gap and dramatically decrease health inequity in this country.

My hope is that by explaining, and potentially convincing you of, their inevitability and the health inequity that will arise from delaying coverage, the conversation shifts away from “should these be covered?” to “how do we ensure everyone who needs them is covered as soon as possible?”

How do we, collectively, best fight for patient access to these new revolutionary treatments?

This post is not to persuade you that obesity is a disease and is worthy of ongoing high quality healthcare, or that obesity is not a failure of willpower. To do so would be a distraction. You can read more about obesity and GLP1s here.

Why are GLP1s inevitable?

There are three overarching reasons the widespread use of GLP1s (and the adjacent drug classes) is inevitable. I’m going to walk through them individually, but it is the confluence of these three factors that will create the overwhelming force for their pervasiveness.

The prevalence of obesity and the demand for an effective solution

The clinical efficacy and scalability of GLP1s

The economic incentives of the healthcare industrial complex.

1. Prevalence and demand

First, let’s outline the prevalence of obesity. Obesity is the most common chronic disease in the United States. We outlined its prevalence in more detail in our Obesity: An Accusation Audit, but here are a few important statistics to pull in:

Population level:

74% of the U.S. population has overweight or obesity.

42% of adults and 20% of children and adolescents have obesity as measured by BMI (CDC)

~50% of US adults will have obesity and nearly half of them will have severe obesity by 2030 (NEJM study).

Specific demographics:

I wrote more about specific demographics here and the often gross oversimplification of referring to obesity as a “disease of the poor and uneducated,” as that link becomes more tenuous when you break down the data by different criteria. But the associations with certain populations cannot be ignored and are essential to our understanding of groups that are more impacted by the effects of having overweight and obesity. The CDC put it well when it wrote, “The association between obesity and income or educational level is complex and differs by sex, and race/non-Hispanic origin.”

A few important statistics to reference:

Lower income women more impacted: the prevalence of obesity decreased with increasing income in women from 45.2% to 29.7% (less so for men by income)

Lower levels of education more impacted for certain groups: Non-Hispanic white women, Non-Hispanic white men, Non-Hispanic black women, Hispanic women

Certain races more impacted by overweight and obesity:

Obesity based on race (CDC NHANES):

ADULTS: Prevalence of adults aged 20 and over with obesity, by demographic characteristics: United States, 2017–March 2020

Second, the demand for an effective solution is hard to comprehend for those who are not either treating patients or afflicted by obesity. Patients have often been struggling with obesity for 5, 10, 15 years. For many, it’s a lifelong struggle and one for which they have been:

Stigmatized or bullied by everyone from colleagues to strangers to healthcare providers

50% said they would prefer to work from home due to feeling insecure about their weight

74% of medical students exhibited implicit (67% explicit) weight bias (source).

Implicit weight bias scores were comparable to reported bias against racial minorities. Explicit attitudes were more negative toward people with obesity than toward racial minorities, LGBTQ people, and lower income people.

MDs, on average, also showed strong implicit anti-fat bias (Cohen’s d = 0.93). Implicit attitudes about weight among all test-takers were strong among both males and females (source)

Told it’s a matter of personal failing of self-discipline or willpower when it’s not

See Ro’s Obesity: An Accusation Audit for why obesity is a disease and not a failing of willpower.

Peddled ineffective solutions and empty promises for decades

87% of patients with obesity have tried to lose weight in the last 5 years with at least 3 different methods.

66.7% of adults with obesity tried to lose weight in the last 12 months according to the CDC.

Here are a few statistics that I hope illuminate the demand for an effective solution for obesity (and specifically GLP1s).

51% of patients said they would stay at a job they didn’t like if GLP1s were covered

44% said they would literally change jobs to get GLP1 coverage

15-30% said they would rather walk away from their marriage, give up the possibility of having children, be depressed, or become alcoholic than be obese

5% said they would rather lose a limb

4% said they would rather be blind

People are staying home because they feel judged. They are staying at jobs they hate. They are willing to quit jobs they love. They are willing to end relationships with people they love. They are willing to lose a limb and even their sight. I don’t point to these things lightly. They show the depth of pain some people are in and it’s often overlooked or dismissed by our society. Think about the above and try to find another problem patients feel as strongly about. There won’t be many.

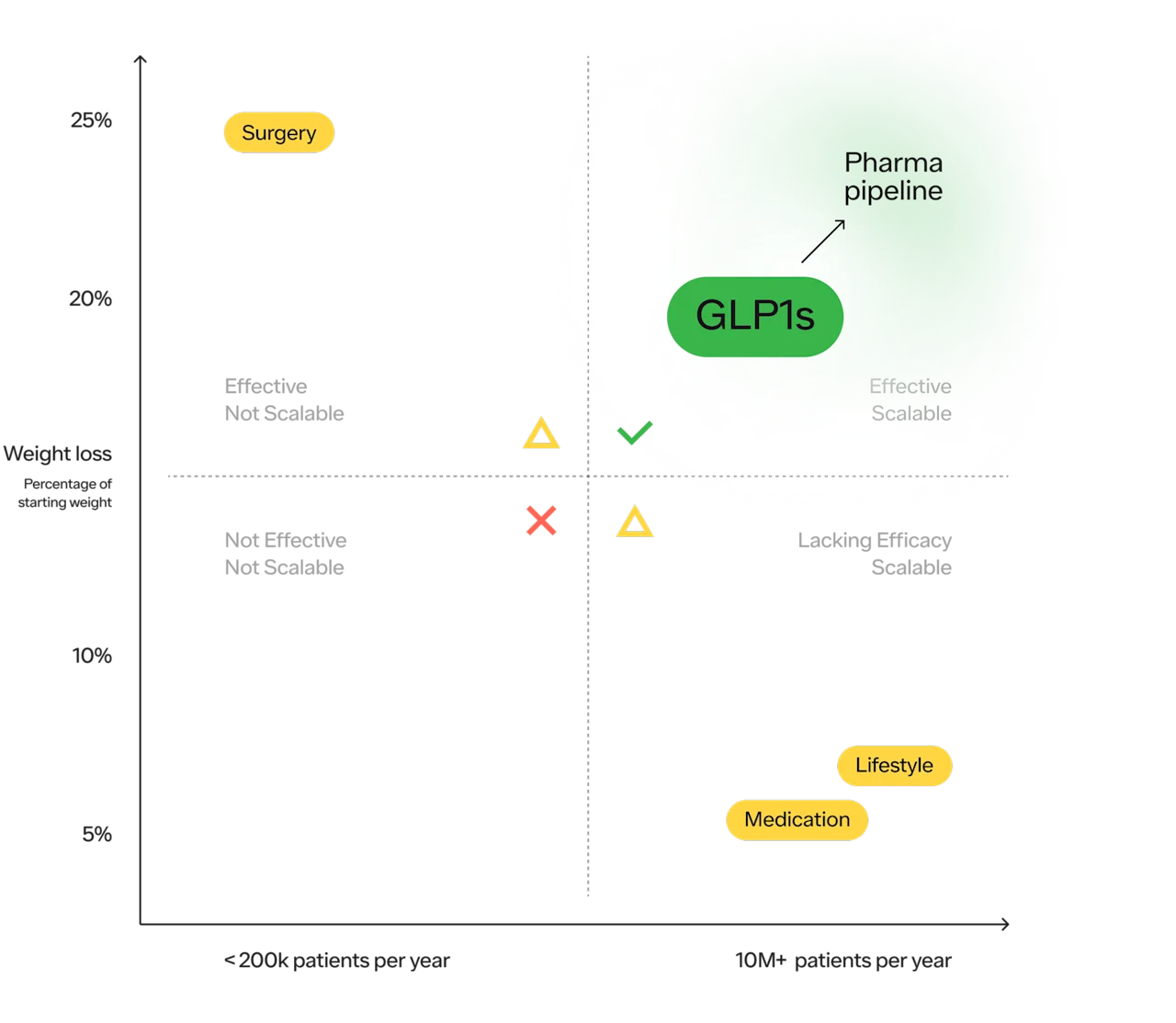

2. Clinical efficacy & scalability

I expounded on this in more detail in our accusation audit, but I will do my best to distill it here because I think reiterating the efficacy and scalability of GLP1s is essential to their inevitability, as it explains why healthcare providers will support of their use.

The key to solving any problem that impacts hundreds of millions of people is to have a solution that is both extremely effective and extremely scalable. And, for the first time, we have both an effective and potentially scalable solution to help millions of people struggling with obesity — which is why so many healthcare providers are incredibly excited about the potential of these drugs.

Eric Topol wrote, in a blog post titled “the new obesity breakthrough drugs,” “The global obesity epidemic has been relentless, worsening each year, and a driver of “diabesity,” the combined dual epidemic. We now have a breakthrough class of drugs that can achieve profound weight loss equivalent to bariatric surgery, along with the side benefits of reducing cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension and hyperlipidemia), improving glucose regulation, reversing fatty liver, and the many detrimental long-term effects of obesity such as osteoarthritis and various cancers. That, in itself, is remarkable. Revolutionary.” (source)

He was also very attuned to the potential of health inequity to be exacerbated — “These concerns can’t be put aside in the health inequity-laden world we live in, that will unquestionably be exacerbated.”

More on this breakdown here.

Whenever assessing the efficacy of any treatment, we must weigh its benefits against its potential risks. The greater the benefits, the greater the tolerance of the potential of adverse events.

With any treatment, there is a statistical likelihood of a patient experiencing a set of benefits and a statistical likelihood of their experiencing a set of adverse effects. The challenge is that the decision to take a prescription drug is a shared decision between a patient and a provider that is forward looking.

Which means that whether it is the “right decision” is probabilistic before making the decision and deterministic in retrospect.

This makes the discourse about any treatment, but GLP1s in particular, extremely challenging.

There will be specific cases where the adverse events were greater than the benefits for an individual in retrospect (there will be many of these given just how many people will be on these drugs)

There will be new adverse effects that we do not know about that only arise as millions of people, from a variety of ages, sexes, races, and background take this medication for years to come

Real world evidence stemming from a diverse patient population over the course of years will add to our domain knowledge — the foundation of which is clinical trials, which serve an extremely important purpose but do have real-world limitations.

Based on the data we have now, I, and many others, believe the benefits strongly outweigh the risks for certain patient populations. This does not mean that this is the case for everyone forward looking or in retrospect. Below is some of the data I find most compelling (not comprehensive).

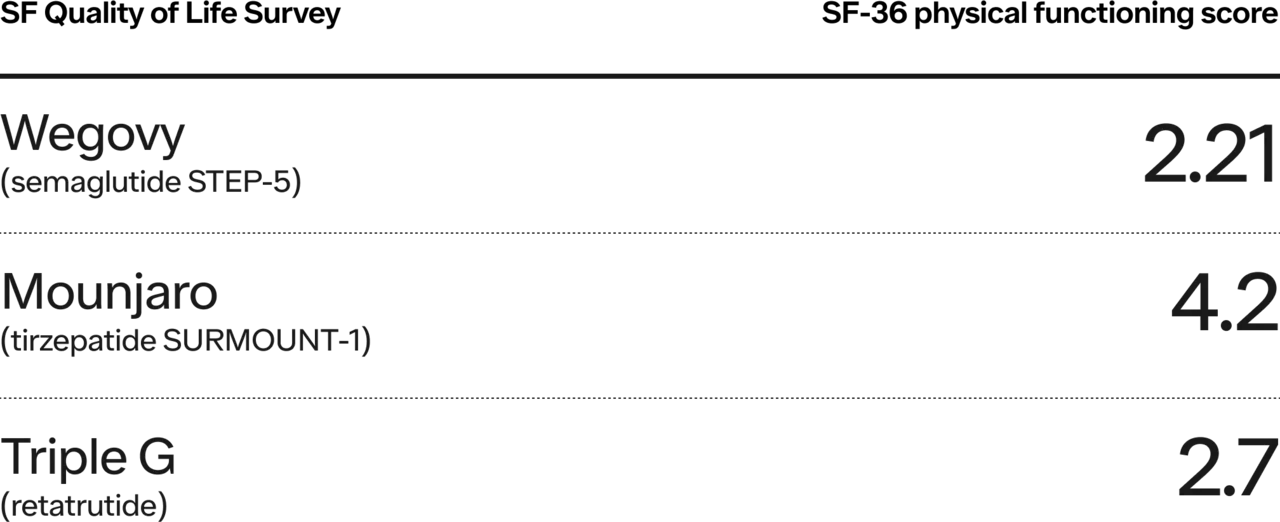

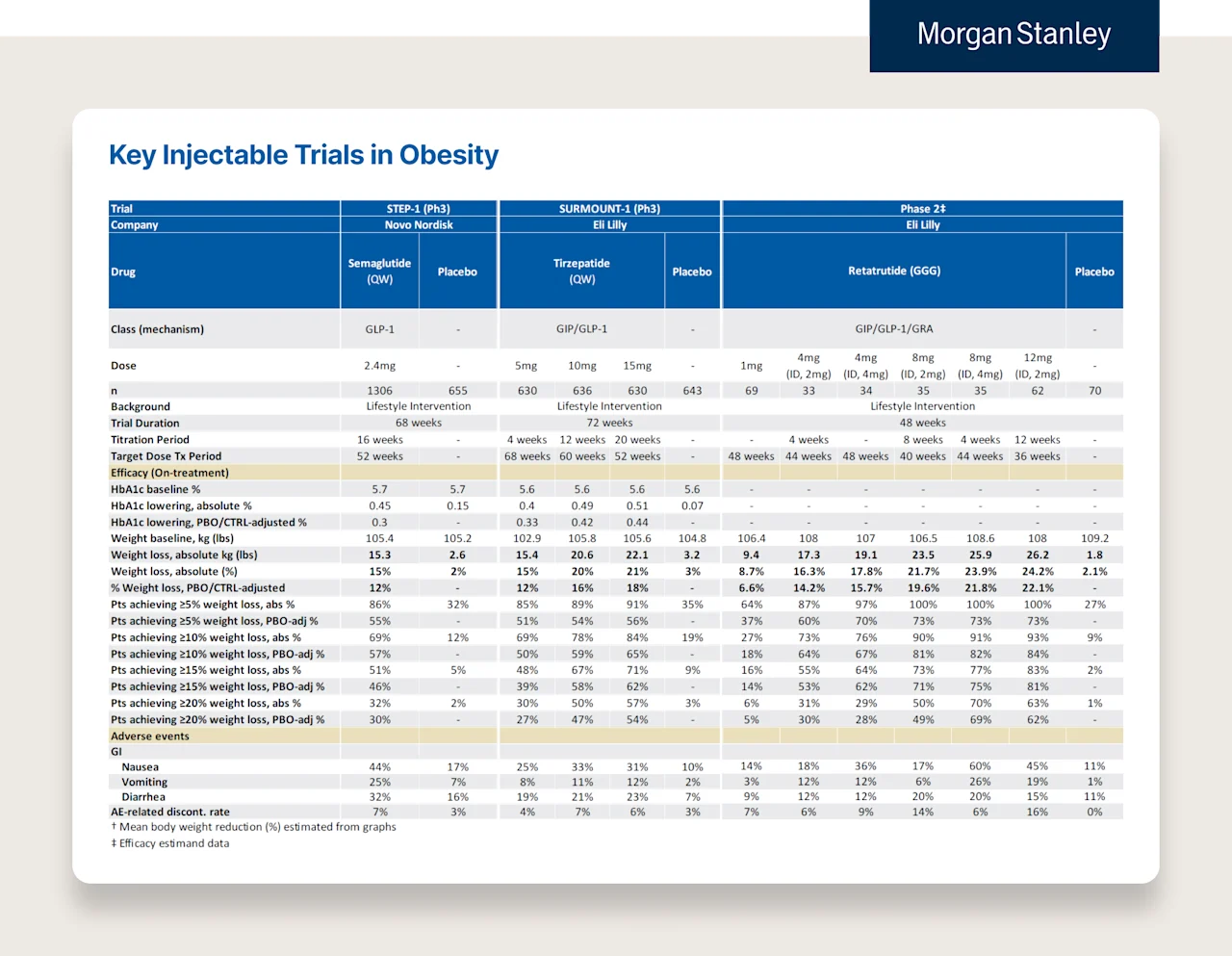

Below are two charts from Morgan Stanley’s “Rising to the Obesity Challenge” paper. The first is weight loss for patients who have T2D and Obesity. The second is a breakdown of three of the most notable trials for weight loss drugs (e.g., Semaglutide, Tirzepatide, and Retrutide, the latter is not yet available).

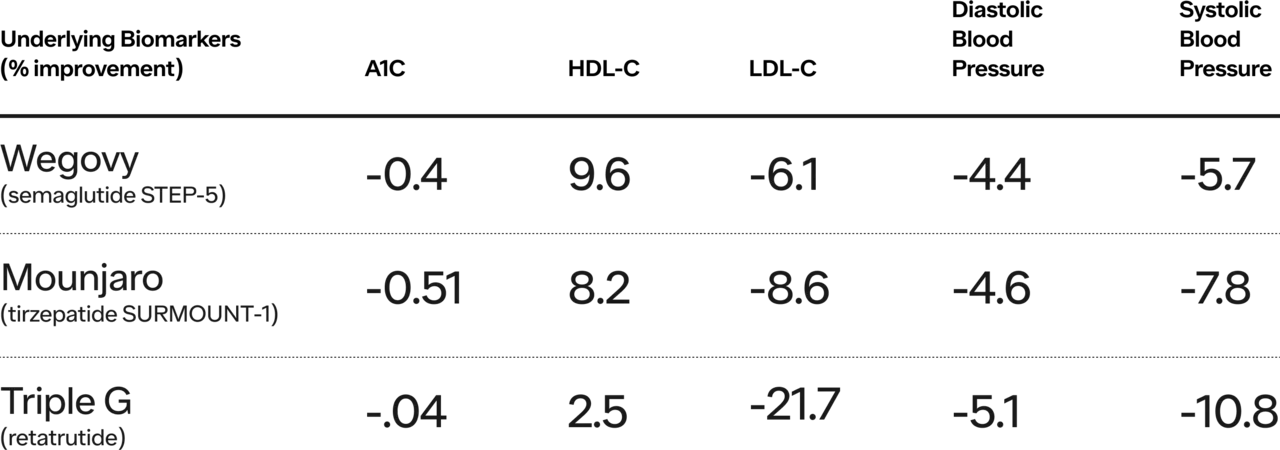

In addition to demonstrating the improvements in A1C illustrated in the above chart, the trials also showed improvements in other important underlying biomarkers.

Other noteworthy benefits:

Quality of life:

HFpEF: Heart Failure preserved ejection fraction (most common type of heart failure in the elderly) and obesity: treatment with semaglutide (2.4 mg) led to larger reductions in symptoms and physical limitations, greater improvements in exercise function, and greater weight loss than placebo.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction has been a much more difficult version of heart failure with limited therapeutic avenues vs other types of heart failure so this is pretty significant. LINK

Kidney health: “On October 10, the drug manufacturer Novo Nordisk announced that it would stop a major trial testing the effect of semaglutide (Ozempic) on diabetic kidney disease one year ahead of schedule. The trial showed the drug was so effective, it seems, that an independent panel recommended there was no need to continue.” (source)

In addition to my personal opinion, there is widespread belief in the medical profession that the benefits outweigh the risks for a significant percentage of people in the United States.

This is evident by the fact that there is currently a national shortage of Wegovy, Saxenda, and Mounjaro.

Even if you disagree with the clinical evidence above, the strongest prima facie evidence is that there are millions of people who:

Want this treatment based on their understanding of the benefits & risks

Are eligible for on-label treatment of this drug based on FDA approval

Have healthcare providers who have determined it would be safe and appropriate for them to receive treatment

Healthcare provider “demand” for their patients is in the millions. It is so great that the CEO of the manufacturer of Wegovy recently said, “But I have the sense that it could actually take quite some years before we have actually fulfilled the demand out there. … We are just scratching the surface, so to say.” (source)

And this is at current prices.

—

Some of the above might seem reductive or over simplistic. That’s fair, but I believe the broad strokes are accurate, and constant caveating or additional nuance would turn a long blog post into a book with the exact same takeaway. I wanted to highlight the following about obesity:

Single largest patient population of any chronic disease in the country

Traditionally marginalized groups are more affected by it

The numbers are growing

Patients want a solution desperately

Healthcare providers desperately want them to have it

In the history of medicine, there has never been a treatment where the above five criteria are true!

The challenge: the current solution costs $10-15k per year.

Let’s say, at this point, we agree that there is a new transformational treatment that >100M people are eligible for and want, and their doctors want it, too.

But that doesn’t necessarily make its dominance inevitable. True. It’s necessary but not sufficient.

But, what if it were free? If it were free, would you think its widespread use would be inevitable?

The reason I ask is because it will be free. Or close to it. It will simply take time. Let’s take it to the extreme just to highlight the point — do you have any doubt that in 30-50 years GLP1s (whether oral or injectable) will cost the same amount that a statin does today (~$20 for a year supply)?

In the next section, economic incentives, I’m going to walk through:

Why the drop in price to “nearly free” is inevitable over the course of the next 30 years

Why some of the key current players of the healthcare system want the prices to be high (which is why it will take time)

As a result, unless we do something about it, the current incentives to delay that inevitable drop in price will delay access and increase health inequity.

3. Economic incentives

1. Why the drop in price to “nearly free” is inevitable over the course of the next 30 years

One of the things people often miss about healthcare is that drugs, over a long enough time horizon, have been the single most effective, most scalable, and cheapest form of healthcare ever invented — from treating infectious diseases to chronic disease management. The problem that we all often wrestle with is that the pricing of these drugs is almost unlike any other product. It often starts out extraordinarily expensive and then, over time (which can vary in length), it decreases in price 90-5000% or more.

For good reason, this doesn’t feel fair.

Why does something that costs pennies or a few dollars to make cost thousands of dollars?

Why is it so much more expensive in the US? Why does the US “fund other countries' access to these innovative drugs before our own citizens?”

Is this the best way to fund innovation? Is this the best way to incentivize pharma R&D?

All great and hard questions. But, for this point, I don’t want to get into the flaws of this system, of which there are many. There are books written about this topic, and there are brilliant people, much smarter than I, who have almost polar opposite ways of attempting solving this problem. I simply want to explain what happens and why (reality), not what should.

What happens to the price of a drug over the course of its life?

There are three life cycles to the price of a drug:

Branded version only (~10 years)

Branded with one exclusive generic (~180 days)

Branded & multiple generic alternatives (ongoing)

Branded version only (10 years) => Most expensive

The price of a drug when it first comes out is often extraordinarily expensive. The high-level idea is that a pharma company took a big risk investing a lot of money (hundreds of millions, sometimes billions), years if not decades, with an unknown outcome (i.e., is the drug going to work? If so, how well?). They need to make a significant return for this investment (i.e., ROI) for the investment to be “worth it” (i.e., profit to reward shareholders and to support continued investment in future drug innovation).

Because of the way drugs work–very difficult to invent but usually very easy to replicate once invented–we currently grant drugmakers patents, which are legal monopolies with expiration dates. During that time period, when the drug is “on patent,” drug companies exert legal but monopolistic pricing. Again, whether this is the right method of funding innovation is a separate question.

For instance, GLP1s have been around for about 18 years but not in the same form with the same efficacy and side effect profile. It took almost two decades to overcome the challenges of early versions (the median time between target discovery and drug approval has been 25 years):

Shorter half lives: the early version of GLP1s didn’t last very long (broken down in GI tract) so people had to take them 2x per day

Less Effective: Saxenda, an early GLP1 injectable, resulted in 7-9% weight loss compared to current GLP1s/GIPs that are showing 15%, 17%, 22% and 25% average weight loss (pending drug, dose, phase of trial, population tested).

There are more challenges the manufacturers have had to overcome to get where we are today. Scientists built on top of one another for decades, and companies invested in an unknown financial outcome in an often dismissed category. There was significant risk, and we want a system that can generate an appropriate reward. But how much?

So what happens when the patent eventually expires?

When a patent expires, there is usually a brief period where a single generic manufacturer is given exclusive rights to make the drug for 180 days. This is called the Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Period.

Quick history aside for context:

The Hatch-Waxman (or Waxman-Hatch depending on which side of the aisle you’re on) was an act in 1984 that created a compromise between generic manufacturers and brand name manufacturers of drugs. While there are many nuances, the agreement boiled down to brand name manufacturers extending their patents on approved drugs and generic manufacturers receiving a dramatically reduced approval process to manufacture a generic version of the drug. Instead of needing to file an entirely new “New Drug Application,” they were instead able to file an ANDA (abbreviated new drug application). This application process is how generic manufacturers are granted approval to manufacture drugs when they go off patent.

Branded with one exclusive generic (~180 days) => Less expensive but still expensive

To incentivize generic manufacturers to make a generic alternative quickly (to incentivize the reduction in the drug’s price), one generic manufacturer is granted a brief 180 day exclusive window where they can be the sole distributor of the generic drug and charge a higher price and earn more profit before other generic manufacturers can enter and drive down the price further.

Branded & multiple generic alternatives => Least expensive (Open Season!)

So what happens when:

The patent expires, and

Any generic manufacturer can file an ANDA and make the drug

There are two main factors that determine a drug’s price when a patent expires.

What was the market size for the patented drug before it expired?

How many manufacturers plan to make a generic version?

As I’m sure you can intuit, the answer to the first question often determines the second. The larger the market when the drug was on patent, the more generic manufacturers that will enter the market.

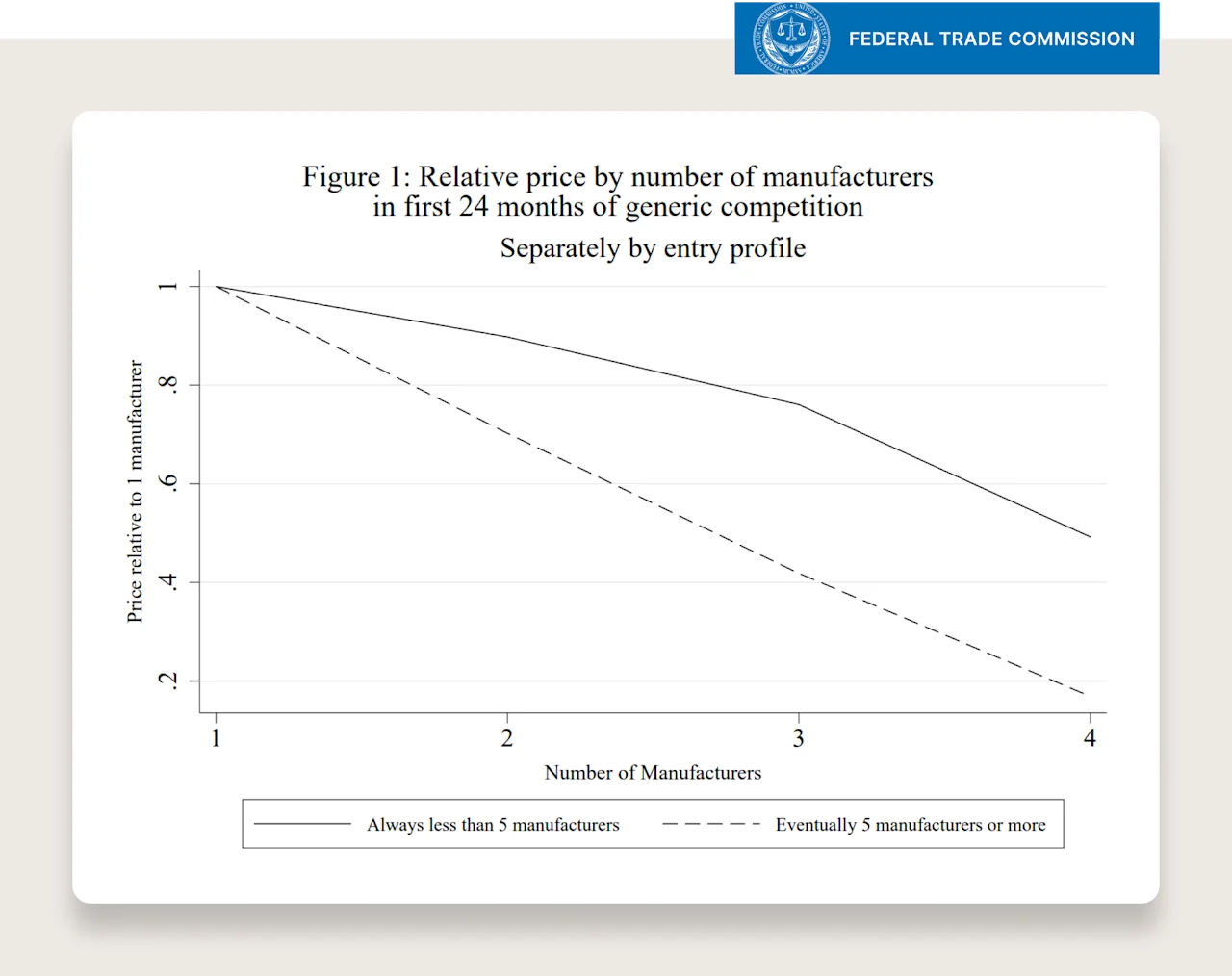

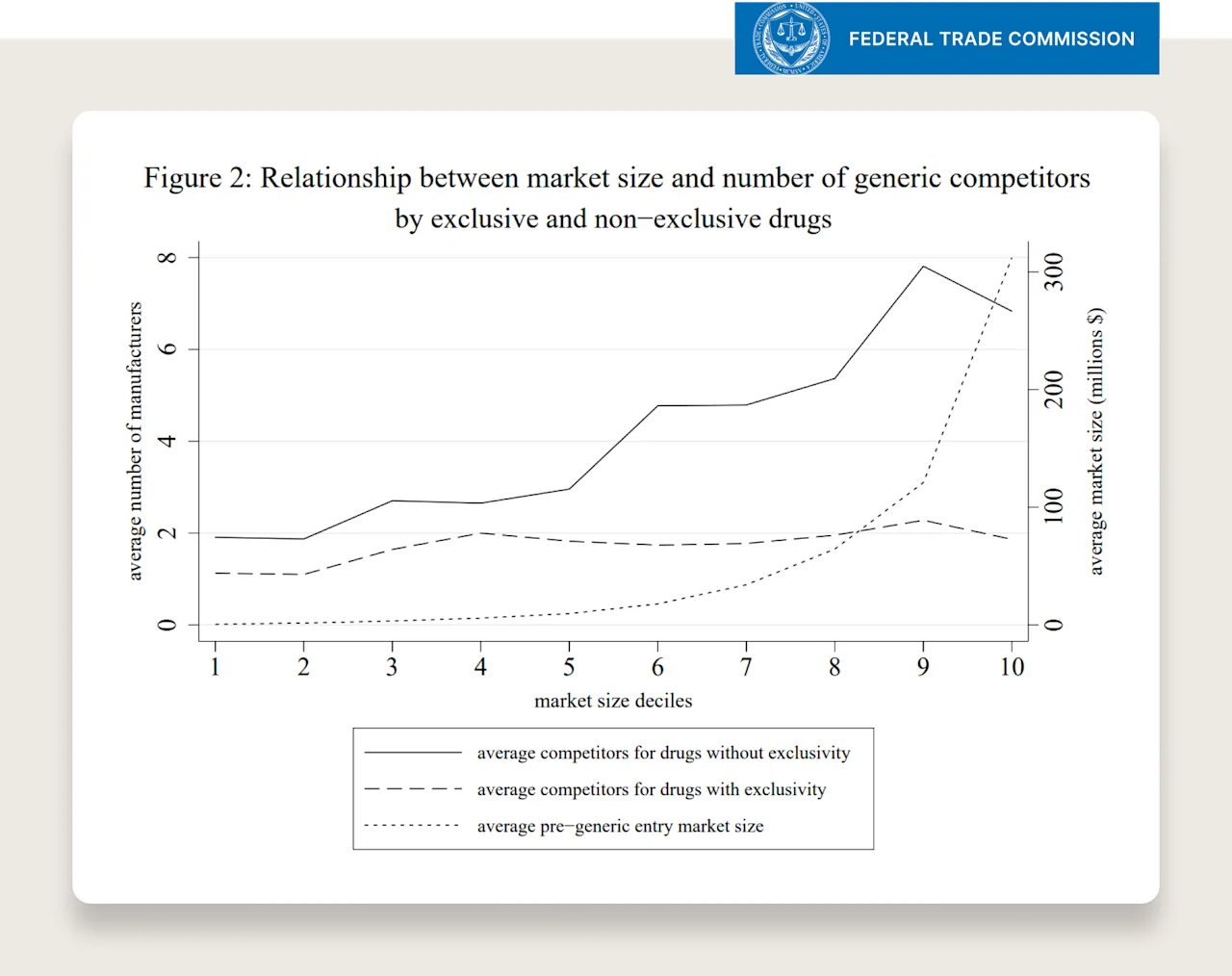

Fortunately, we don’t have to guess — “how much?”. Here is a paper published on the FTC’s website titled, “The Effect of Generic Drug Competition on Generic Drug Prices During the Hatch-Waxman 180-Day Exclusivity Period.”

There are two figures in the econometrics paper that tell the story.

First graph takeaway: if the drug, when on-patent, was in the top decile of market size, it will likely spur ~7 generic manufacturers to create their own generic option.

Second graph takeaway: if a drug ever has more than 5 generic manufacturers, after 24 months of competition from these generic manufacturers, the price of the drug will be 10% of the original or lower.

Putting the two together: the larger the market, the more competition, the greater the percentage decrease in price from competition after ~2 years.

Quick summary: Part 1

Prevalence & Demand:

Single largest patient population of any chronic disease in the country

Traditionally marginalized groups are more affected by it

The numbers are growing

Patients want a solution desperately

Clinical Efficacy:

Clinical trial data suggest benefits outweigh risks for certain patient populations

Actions of healthcare providers suggest they strongly want patients to have access

Pricing Timeline:

Branded drug will start with monopolistic prices for ~decade

The patent will eventually expire

The bigger the market (outlined above), the more competition, the greater the percentage price decrease

Adding up the above, over a long enough time period, the price will come down to a very affordable price based on the current size of the market.

Statin Example

Quick call out on insulin as the most common counter example:

Insulin pricing:

Andrew Pannu put this extremely well in this post and provided a great primer on the affordability of insulin over time. Some quotes from his post:

“Insulin discovered 100+ years ago has gone through extensive improvements from animal (i.e. pig, ox) to human and lastly to human analogs. These took significant R&D $ and naturally will see price hikes.”

“Patients have been able to access cheaper forms of insulin for years, but those come with lower half-life and sharper "peaks" that trigger unwanted side effects. We should continue to encourage innovation for "old" drugs. “

“Manufacturers are actually not benefitting from [increase in price] in the case of insulin - net prices have consistently fallen YoY for the major branded insulin products”

“Recent initiatives to cap OOP insulin cost & launch branded generics are the right thing to do.”

“Significant variability in insulin cost that patients pay often stems from inadequate or no insurance coverage.”

“This is another area where sensible legislation should be encouraged to re-align incentives & end this cycle of artificial price hiking to enrich middlemen.”

From the primer linked above: “Between 2003 and 2016, the list price for a vial of NovoLog, a popular insulin analog, increased by 310 percent, after adjusting for economy wide inflation. However, the net price received by the manufacturer, Novo Nordisk, decreased by 21 percent over the same period”.

2. Why some of the key current players of the healthcare system want the prices to be high (which is why it will take time)

This is not a comprehensive explanation (again, there are books on this subject), but I’ll do my best to keep this part short and sweet.

The majority of the key stakeholders in the healthcare system are economically enthusiastic about both the rise of GLP1s and the high prices (even insurance companies). Let’s break it down.

Insurance companies:

Initially, an understandable reaction would be that insurance companies don’t want healthcare costs to increase. This isn’t always true. Here’s why. Insurance companies, like any other company, want to grow and to make more profit. However, unlike most companies, insurance companies' margin (i.e., medical loss ratio) is fixed. As a result, there are two ways for them to make more money:

Sign up more people (i.e., more volume)

Increase prices (i.e., revenue per customer)

It’s hard to sign up more people (relatively) when the largest insurance companies have tens of millions of people (it’s like FB trying to grow the number of users in the US – they are tapped out). So an insurance company needs to grow the revenue per customer to show significant growth.

But, they can’t just raise prices if their costs are the same (i.e., increase their margin) — their margin is fixed. They need the underlying costs of healthcare to rise for their cumulative profit to grow.

But, there is an important nuance. They don’t want costs to rise unexpectedly. They hate surprise increases in costs (their margin has a maximum… but not a minimum). They benefit from predictable increases in spend. This allows them to factor the costs into their premiums, satisfy margin requirements, and increase cumulative profit over time. Healthcare costs rise, insurance premiums rise, insurance company profit rises, and all while margin stays the same.

As it relates to GLP1s, insurance companies are excited (even if they can’t say the quiet thing out loud) on a multi-year time horizon. It's the surprise uptake in GLP1s they don't like (i.e., greater expense than expected). But if they can predict it or space out the increase as they get a handle on it, over the next 2-3 years they will factor this into their premiums and increase their overall profits.

This is where you’ll see insurance companies put up roadblocks to treatment. They’ll ask patients to “fail other methods first and take personal responsibility” before covering GLP1s. Do we ask patients to fail lifestyle interventions before they get treatment for hypertension? Do we require patients to use demonstrably less effective treatments? Especially knowing the negative effects of time spent with obesity.

Insurance companies don't want to come out and say the quiet thing out loud — “we want costs to continue to rise YoY because that is how our profit will grow over the coming years because we can’t sign up enough people to really grow that quickly. If costs don’t increase, our business won’t grow.” That's politically untenable. But they are less worried about it than they might seem over the coming years.

Here is a receipt for the internet 5 years from now — even if the price of GLP1s are still extremely high, insurance coverage will be much higher than it is today (even if it gets worse before it gets better), all of our premiums will be higher as a result, and the largest insurance companies will increase their profit. It will be under the explanation of health benefits, employer requests, government pressure, and patient demand.

“Most adults (80%) say that insurance companies should cover the cost of weight loss drugs for adults who are overweight or obese, while half of adults (53%) say insurance should cover the cost of these drugs for anyone who wants them to lose weight.” See more on patient sentiment towards coverage — KFF

PBMs:

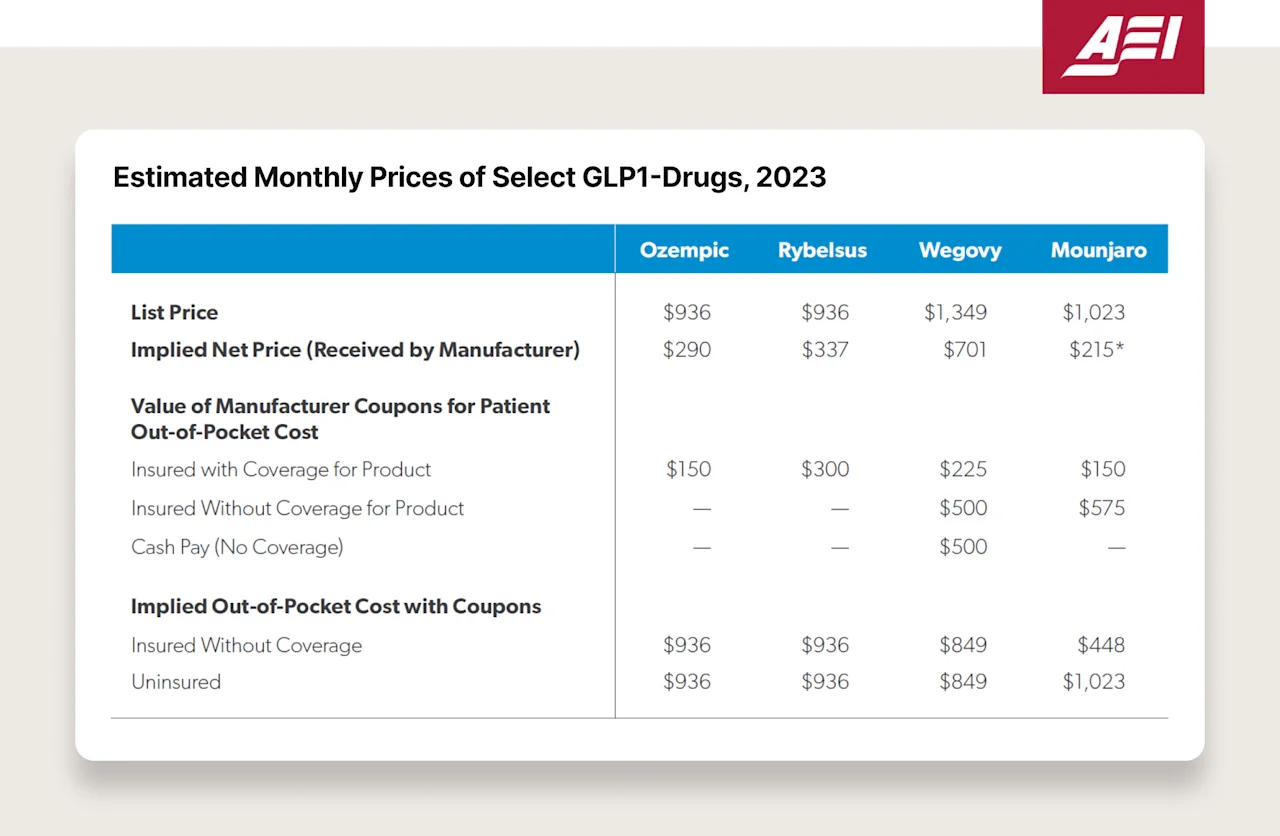

PBMs will make extreme amounts of money from GLP1 rebates. While we might see the list price of $1000- $1500 for GLP1s, no one in the healthcare industry, except cash pay patients, is paying that amount. There is a much longer explanation about the money flows between insurance companies, PBMs, pharma, and pharmacies (one that I’m not sure any single individual really understands down to individual transactions as there is a tremendous amount of opacity even within individual contracts).

But, one of the most important forces within that flow of money to understand is that a pharma company is probably receiving ~$500 for GLP1s whose list price is $1000. The remaining $500 is given to the PBM in the form of a rebate. This rebate is usually based on a percentage of the list price (i.e., “50% rebate”).

This has the incredibly unfortunate result of incentivizing pharma companies to increase their prices. The higher their prices, the more the PBM makes from a rebate. Think about two drugs, where the PBM gets a 50% rebate.

$2000 — PBM gets $1000

$500 — PBM gets $250

Which one do you think the PBM prefers? This is one the reasons pharma companies aren’t incentivized to undercut the market with a lower price and steal market share. I’m not losing sleep for pharma companies, but they are often caught here between a high price and market share (given the PBM’s position) or a low price and no market share from these distorted incentives.

Side note: an example of this playing out in reality is that the cash prices of insulin have been increasing over the last decade but the “net price” (amount pharma receives) has been decreasing.

Here is a table of the estimated “net price” received by Novo and Lilly. The list price is $936 but Novo receives $290 (source). 🤦

Pharmacies:

This is pretty straightforward (for the most part, there are always exceptions and nuance in healthcare). Pharmacies make money on prescriptions. It varies by drug, insurance contract, distribution method (e.g., retail v.s. mail). But generally, the more prescriptions that a pharmacy has, the better.

We’ve seen CEOs of the largest pharmacy chains in the country reference GLP1s in earnings calls and share that they are generating very strong revenue for them. Particularly for retail. The more people that walk into the pharmacy in-person, the better. It’s not by accident that pharmacies are in the back of the store, and you have to walk through a bunch of other things you can buy before you get to it.

One side note worth mentioning with pharmacies. The healthcare industry is dominated by several players (~80% of PBM volume is owned by three companies). Some of these players own multiple parts of the value chain — the insurance company, the PBM, and the pharmacy. This definitely impacts incentives (i.e., an insurance company might lose money on a surprise increase of GLP1 costs but make money on the PBM rebates). It’s really hard to anticipate how all of this plays out in the next 2-3 years versus 5-10 years from now (where all the incentives are more aligned on a longer term time horizon that “more is better”).

Pharma companies:

Pharma invented a product. They want it to be commercially successful. They will work really hard for that to be the case — from patient education to provider education to research on long term health benefits to countless other activities.

Are there opposing forces? Who might not want the healthcare costs to increase?

An oversimplification, but there are three groups that do not want healthcare costs to increase:

The entities paying for the drug (and healthcare more broadly):

Government

Employers

Individuals

The people caring for patients:

Advocacy groups

Providers

The challenge is often that while individuals, employers, and the government all want healthcare costs to decrease, they have different time horizons, incentives, finances and people to worry about — which can make getting alignment quite difficult. The most important thing to a patient might not be the most important thing to an employer (an employer has to think about its entire employee base on a shorter time horizon; an individual has to think about their and their family’s health over the course of their entire life).

Why does delaying coverage accelerate health inequity?

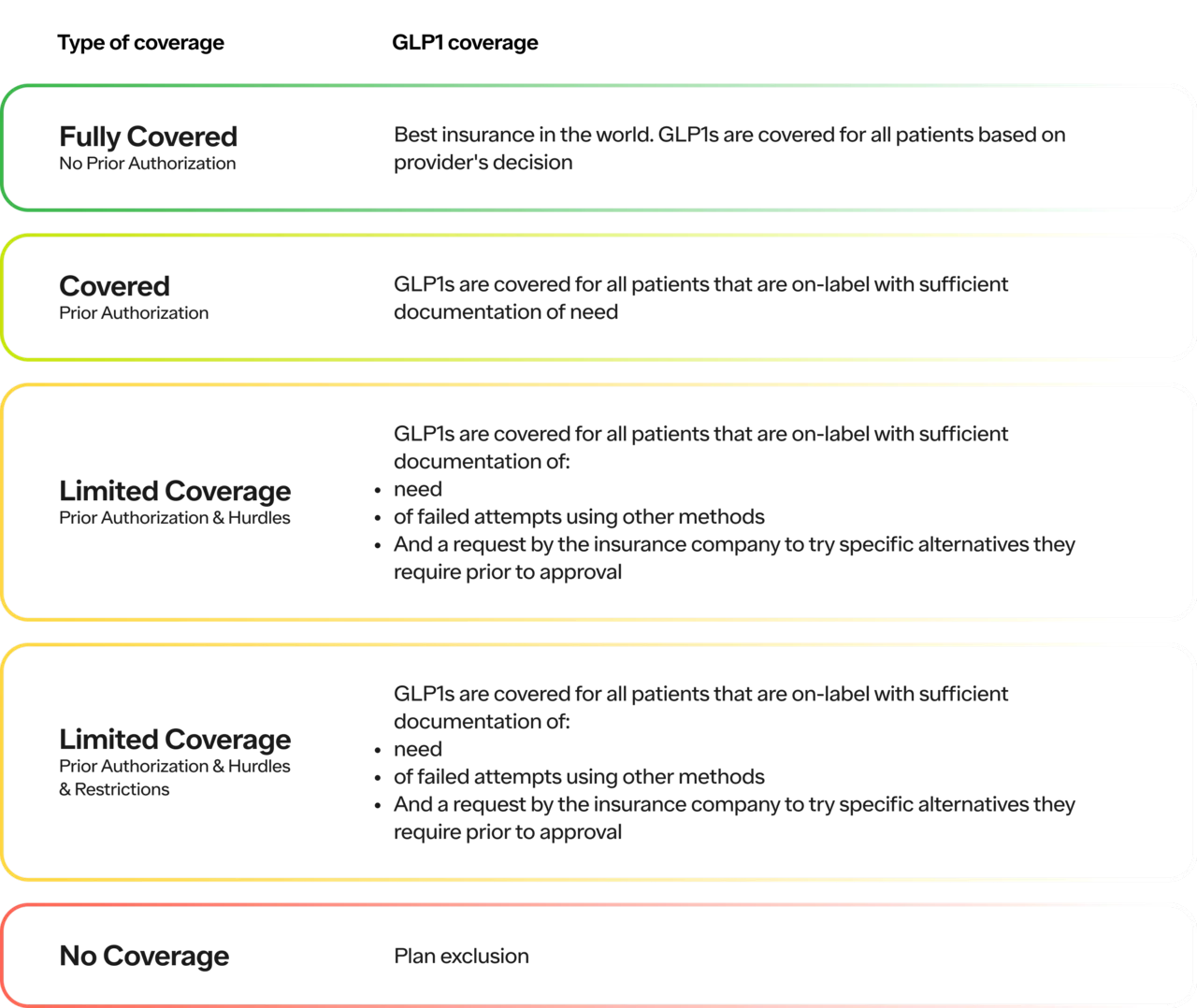

First, let’s break down the different levels of coverage and how that influences access.

Here is a table breaking down the different types of coverage for GLP1s specifically:

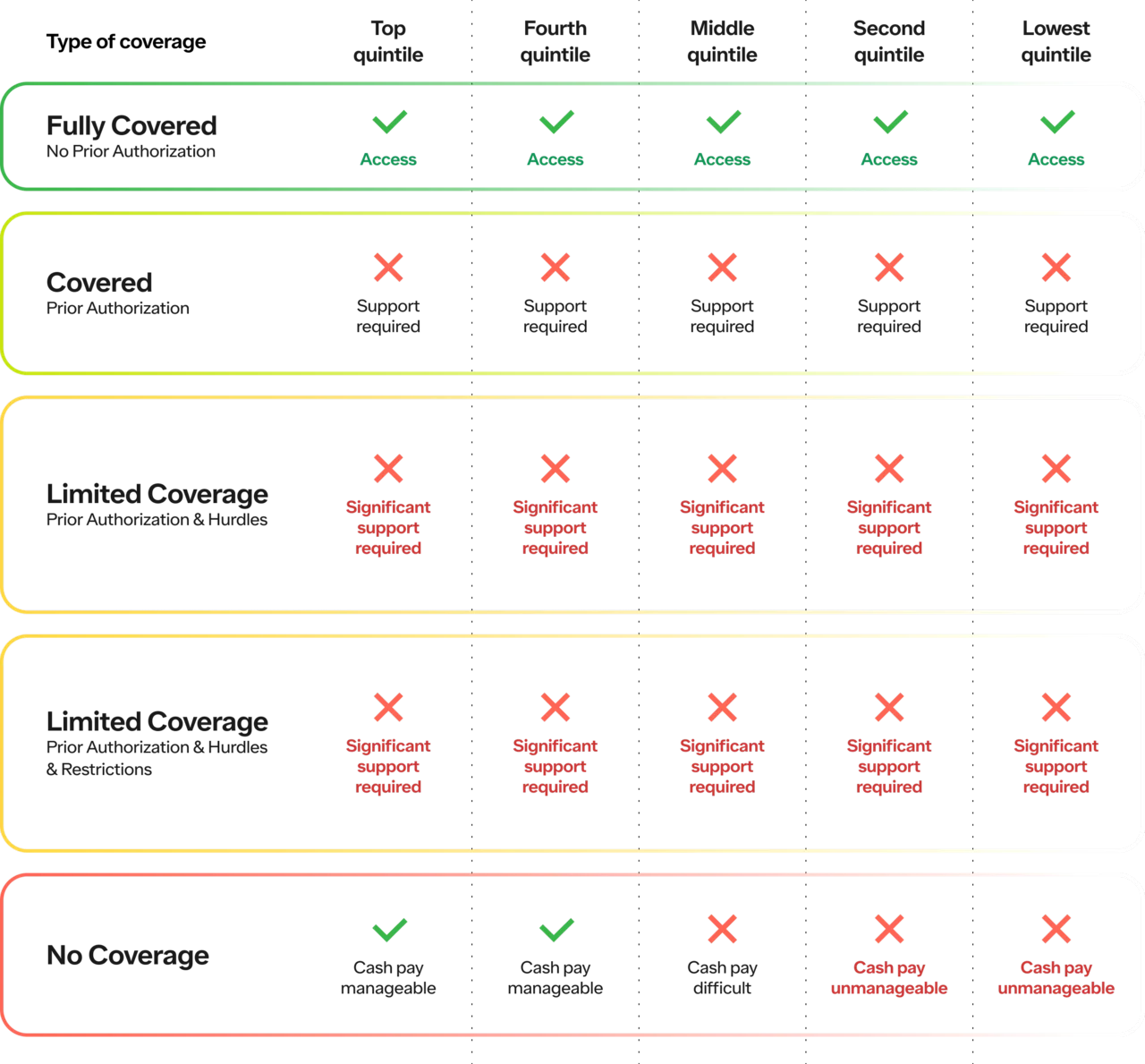

Here is a table breaking down how the type of coverage and level of income influences a patient’s access to GLP1s:

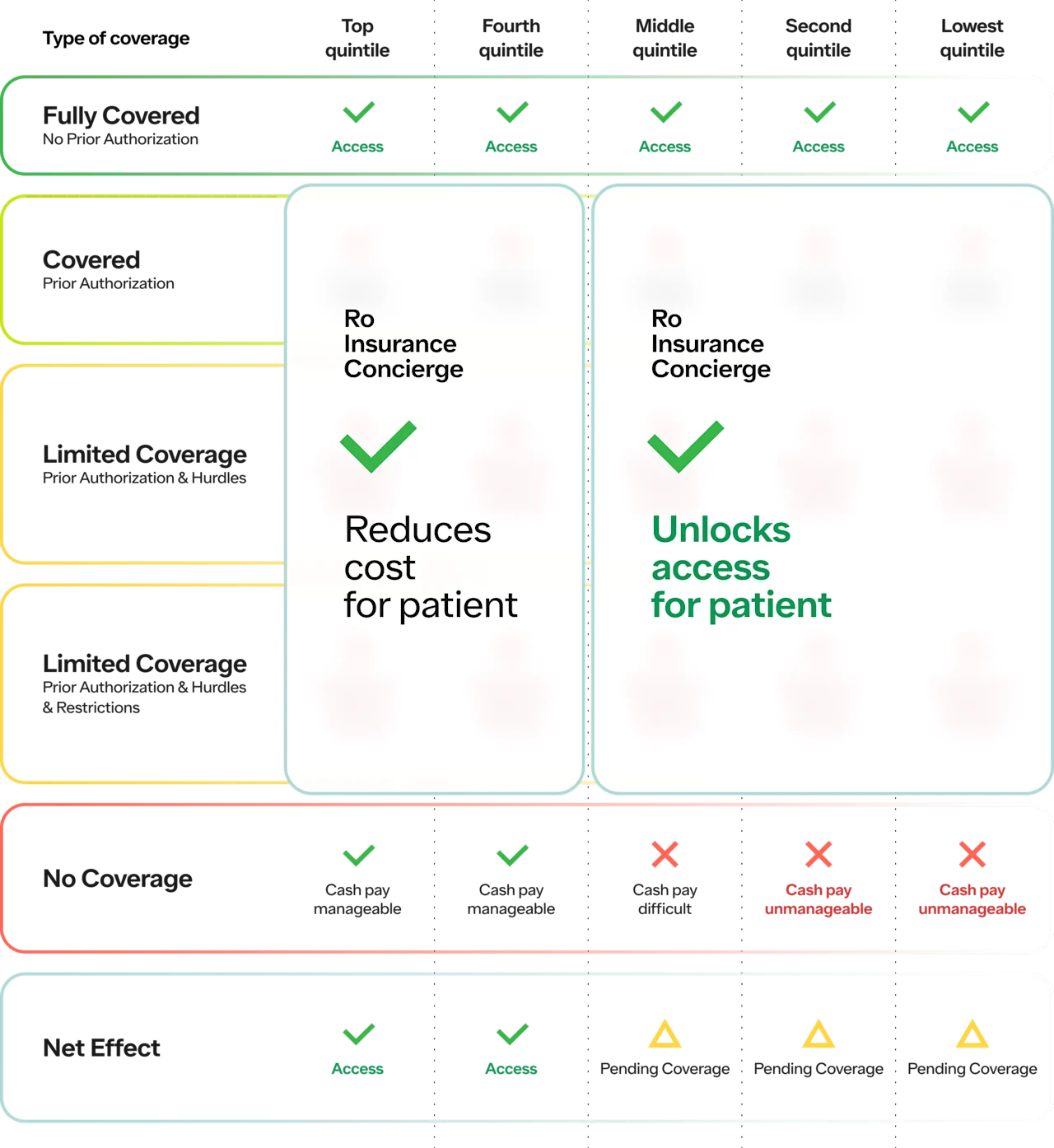

With the Ro Body Program, we take on the middle layer. All the complications related to insurance (e.g., benefits verification, prior authorizations, documentation etc.).

For the top two quintiles, we reduce the cost (if insurance fails, they pay cash)

For the bottom 3 quintiles, we unlock access (if insurance fails, paying cash is extremely challenging and often unmanageable)

The net effect of the status quo is:

Top 2 quintiles, regardless of coverage, will get access

Bottom 3 quintiles, need insurance coverage to get access

Impact of the Body Program on access

One of the challenges in increasing access is that the top two quintiles are the ones that most likely have access to the best doctor’s offices in the world who are going to be best at handling the “significant support required” for coverage (i.e., hand-to-hand combat with insurance companies).

This is one of the reasons why we created the Body Program in the first place — to turn the luxury of a concierge obesity clinic into a commodity that more people can access. And we see this in the data! Patients across ALL income brackets sign up, knowing their only way to access this type of support both from a healthcare perspective and on the insurance administrative side is through a program like the Body Program.

With the Body Program, we’ve been able to help the majority of patients, who come through our doors and are clinically eligible, secure some form of insurance coverage (copays vary by plan).

Without widespread coverage, health inequity accelerates

If you haven’t already, you’re going to hear a lot about why insurance companies or the government shouldn’t cover GLP1s. The cost is “too high,” and the ROI “isn’t worth it”.

This discussion is an important one (and I wish we had it in more places in healthcare because it’s a necessary one). In terms of the ROI, at the most tactical level:

As we mapped above, key stakeholders do want GLP1s to be widespread (even insurance company want them — they just want the coverage to be “spaced out” so they can factor the cost into premiums).

I believe (personal opinion) that the ROI will prove to be worth it over the long term the more we learn about the long term health impacts of this drug class from a purely financial perspective (even at relatively high prices).

ICER wrote, “The health-benefit price benchmark for semaglutide is $7,500 to $9,800 per year” (source). The drug costs $10-15k so we’re closer than we might think. Noteworthy, this analysis was pre the SELECT trial, which showed a 20% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events and ICER has announced that they are redoing this analysis (likely with a higher health-benefit price) once the full SELECT results are released.

Until we have more data, we can’t make a claim either way, and every employer can and should make their own decision.

The employers with high average tenured employees (low turnover) will have the math work earlier from an ROI perspective as they can economically justify multi-year investments in their employees’ health.

Hopefully some of the statistics I shared above regarding patient demand suggests that some employers may choose to offer it as a recruiting technique or must offer it as a retention technique. We've seen this take place recently with employer-sponsored mental health and fertility benefits.

But I want to add an important part to the conversation that I think is missing. In addition to “is the ROI worth it?”, I think we must ask ourselves, “HOW can we make the ROI worth it? And fast?” Because we must in order to increase health equity.

Without widespread coverage:

Higher income patients will get access through either insurance coverage or cash pay

Fewer lower income patients will get access through programs like Ro which can go to battle for them against insurance companies and take on that burden that a concierge practice might

Note: while Ro still increases access, and we see lower income patients sign up every day, I hope it goes without saying that we won’t solve this problem alone. We don’t accept Medicaid. Our service is affordable but does cost money on top of the cost of drugs. We can help (and we’re proud of contributing), but we’re not under any impression we’re a panacea.

So what happens in society over the next 5-10 years if a greater percentage of higher income people can:

lose 5, 10, 15, 20, 25% of their body weight 90% of the time

Helping them get more sleep, feel less joint pain, improve their mental health

improve their A1C, lower their LDL, raise their HDL, and have 20% fewer major adverse cardiovascular events

take the job they love because they aren’t stuck based on coverage

miss fewer days at work

have a rapid increase in their quality of life

have an increase in their quantity of life?

While associations between higher income and higher quality and quantity of life are not new (the gap between the counties with the highest life expectancy in the US and lowest is ~25 years! source), I believe GLP1s, if accompanied by the right healthcare support around them, present both an opportunity to bridge the gap of health inequity and a scary potential accelerant.

Side note: A tough but eye-opening read on the disparity in life-expectancy in the NYT (source). Obesity-related chronic conditions like type 2 and kidney disease are among the top culprits of this disparity (source).

And what are the compounding effects if that differentiated access exists for 5, 10, 15 or 20 years? I don’t believe it will be like other blockbuster drugs. GLP1s (and adjacent drugs) are unique in both their clinical impact (in the near term and long term) and broad applicability. It’s unlike anything we’ve seen before in medicine.

Note: Of course, this should not be a replacement, but a complement, to all of other initiatives in service of increasing health inequity (improving SDOH with better access to food, education, healthcare etc.). It’s essential that we differentiate between obesity prevention and treatment (more on why here from Ro’s CMO Dr. Melynda Barnes), but also not think of them as an “or” proposition. It must be an “and."

Quick summary: Part 2

Reminder of Part 1

Prevalence & Demand:

Single largest patient population of any chronic disease in the country

Traditionally marginalized groups are more affected by it

The numbers are growing

Patients want a solution desperately

Clinical Efficacy:

Clinical trial data suggests benefits outweigh risks for certain patient populations

Actions of healthcare providers suggest they strongly want patients to have access

Pricing Timeline:

Branded drug will start with monopolistic prices for ~decade

The patent will eventually expire

The bigger the market (outlined above), the more competition, the greater the percentage price decrease

Take away from Part 1: over a long enough time period, the price will come down given high demand, regulatory precedent, and economic incentives.

Part 2

Insurance companies:

Fixed margin

Want costs to rise predictably and steadily, not by surprise

In support of GLP1s over time, not immediately, so they can be priced in

PBMs:

Benefit from higher priced drugs with rebates

Pharmacies:

Benefit from volume of prescriptions

Benefit from foot traffic from prescriptions

Pharma:

Benefit from blockbuster drugs

Summary of existing players: four key stakeholders benefit from higher priced blockbusters drugs over a long-term time horizon under most circumstances.

Impact of higher priced drugs on access in near term:

Higher income get coverage and/or pay cash

Lower income solely rely on coverage and therefore have limited access

Take away from Part 2:

Key stakeholders benefit from high prices

Top earners pay cash; lower income rely on coverage

As a result, without widespread coverage, health inequity accelerates

Potential solutions

First, I’m all ears if anyone has any. I don’t sit here and assume this is easy or that it will happen overnight. This post is more of an ask for help and a conversation starter than it is a specific theoretical answer.

In terms of what might work, here is what I’m hopeful for:

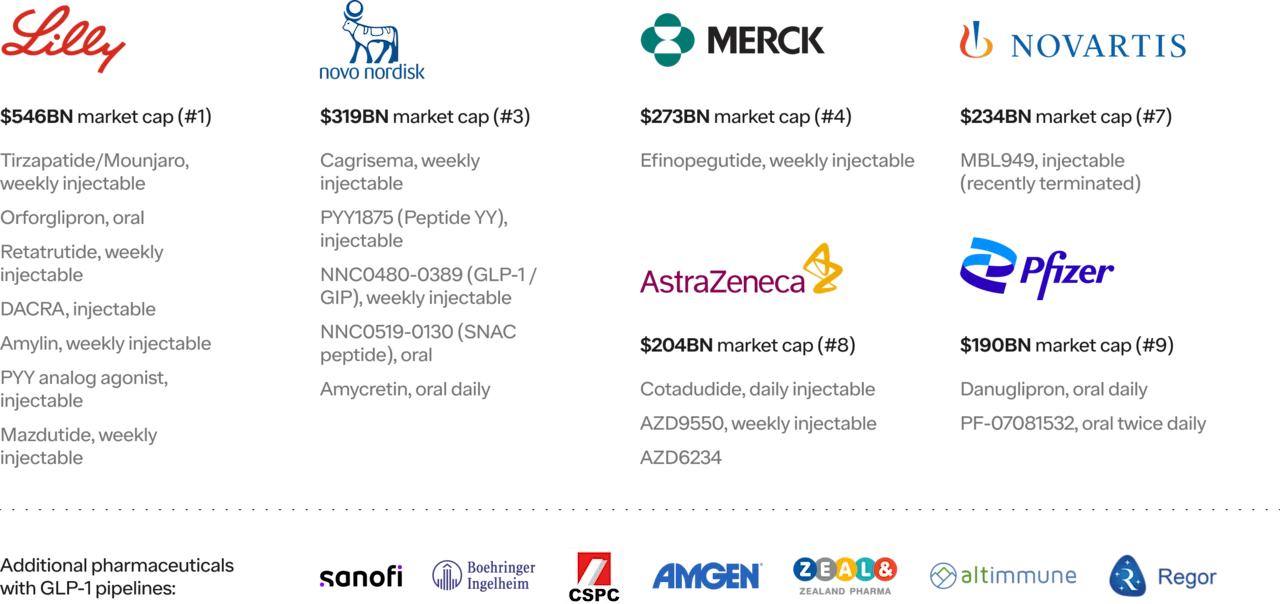

Competition

There are 85 total anti-obesity medications in phase II-III trials as of 2023. Six out of the largest ten pharma companies in the world are working on their own GLP1s. That competition will be great for the stakeholders paying for healthcare (patients, employers, and the government).

Government intervention

No one party in the healthcare system is to blame. It’s often a Spiderman meme situation in healthcare with everyone pointing fingers. And they aren’t wrong; there are problems inherent in the entire value chain and there were, logical, well-intentioned reasons they were put there in the first place. I genuinely believe the vast majority of people in healthcare deeply want to help patients. They are also running a business and playing the game of the rules on the field (yes, of course they try to influence those rules as well — but I don’t think they are doing it with the intent to harm). People at insurance companies don’t want to bankrupt people. Doctors at hospitals don’t want you to need more care. Pharmacists don’t want to charge you more for medication than you can afford.

When the rules need changing, this is where the government can and should step in. Much of what I write may make it sound like I’m a pure “free market” healthcare person. I’m not. I do believe in patient empowerment (and believe they should be in control far more than most). And I believe the most efficient markets are ones where the demand is most distributed among buyers. But, that doesn’t mean I want the government out of the healthcare system! Healthcare is both extremely similar to other industries (and I wish it was even more similar to consumer driven ones) but there is something fundamentally different about healthcare — it can be life and death. Basic healthcare should be a fundamental human right of an evolved society. Dostoevsky wrote, “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” I agree and believe the same judgment can be applied to how we provide healthcare for the less fortunate. It is lower on Maslow's hierarchy of needs, and I do believe it is the job of the government to both set the rules, enforce the rules that protect people, and provide a safety net for the elderly, poor, and disabled.

When it comes to GLP1s, the government has extensive power. From adding GLP1s to their formularies for Medicare (weight loss medications are statutorily restricted from being covered in Medicare Part D) and Medicaid to increasing their negotiating power to changing the way we approve new drugs.

While there is obviously a lot left to do, I do want to call out that I think the governments in the United States, at both the federal and state level, have been extremely forward-looking in pockets.

Anti-obesity medications are covered for all federal employees and their families (~8M people). Started in January 2023.

Medicaid in the following states have started to cover anti-obesity medications in ~10 states (source), with eight more considering coverage (source):

Broad coverage of anti-obesity medications: California, Kansas, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Delaware, Rhode Island and New Hampshire, plus now Connecticut (as of July '23).

Limited coverage of anti-obesity medications: New Mexico, Louisiana, Tennessee, Georgia, South Carolina and New Jersey.

Note: some of the patients most in need (based on obesity rates and location) are under or uninsured — “seven of ten states that have not adopted the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and nearly all (97%) of the people experiencing a coverage gap due to non-expansion are in the South” (source).

And the Inflation Reduction Act has started to push in the right direction on reducing drug prices and unlocking the government, the largest payor, to negotiate drug prices.

Advocacy

Beyond competition (i.e, market forces) and government intervention, advocacy can also make a difference. While the hardest to see the results from in the short term, advocacy can be an extremely powerful force in the long term. From patients advocating to insurance companies, to employees advocating to their employers, to providers and advocacy groups to pharma companies. Will there be a pharma company that does what Pfizer did with Lipitor? Undercut the market with a more effective drug? It was unpopular in the industry (again the quiet thing out loud), but it led to a massive commercial success and more patients gaining access.

Conclusions

With this post, I wanted to:

Walk through the inevitability of GLP1s (and adjacent drugs) over the next 20-30 years with evidence based on patient prevalence, patient demand, provider demand, economic drivers, and historical precedents.

Highlight that given their inevitability, by delaying coverage or cost control we risk the greatest acceleration of health inequity in our lifetime.

Stimulate a conversation early in the public discourse on patient access through the lens of increasing health equity

It is one of my strongest held beliefs that we cannot let the short term cost of this treatment force us to build a system that restricts these drugs, for an extended period of time, to the few with resources or with health care system knowhow. With every ounce of friction we put in front of the clinically eligible, we will accelerate the bifurcation between the rich and/or well insured and the poor and/or uninsured.

We must come together and find a way to accelerate the inevitable price decrease of these drugs and/or widespread coverage. This is a unique circumstance, and it requires unique action.

Thank you for making it to the end. I know there are likely things I’m missing or, with new data and new perspectives, would update my opinion on the above. I’m sharing my thoughts publicly with the hope of learning from yours.

Thank you for spending the time.