Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

You might have heard that weight gain is a possible side effect of using birth control, or maybe you’ve experienced it yourself. So it makes sense to look for the best birth control for weight loss.

Believe it or not, the evidence that birth control causes weight gain is mostly anecdotal, and no birth control options directly cause people to lose weight (IQWiG-a, 2017).

Still, birth control weight gain is a valid concern, one that many people share. Let’s look at which birth control is more likely to cause weight gain and which birth control options are best if you want to avoid gaining weight.

Can birth control make you lose weight?

While many people notice weight changes while using hormonal birth control methods, researchers haven’t found a clear link between the two (IQWiG-a, 2017). In other words, there is little evidence that hormonal birth control causes you to gain or lose weight.

Reviews of the medical literature have found that, while many patients and clinicians notice a link between taking hormonal birth control and weight gain, study trials haven’t established a definitive relationship between the two (Gallo, 2014; Lopez, 2016).

But can you lose weight on birth control? Unfortunately, there are no birth control methods that actively cause weight loss. However, certain birth control options, such as the birth control pill called Yasmin, have diuretic properties, which may cause you to lose water weight (Apter, 2017).

Which birth control causes weight gain?

Although current data doesn’t back up the claim that birth control causes weight gain, when people notice weight gain from birth control, it’s more often when they are using hormonal birth control methods.

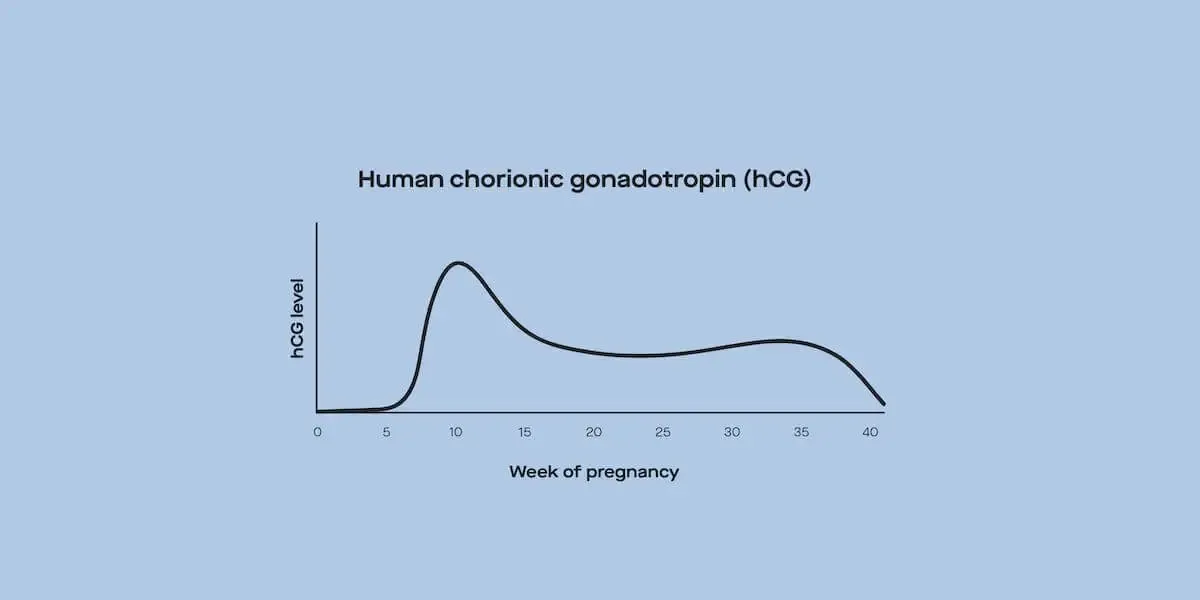

When used correctly, hormonal birth control is usually highly effective at preventing pregnancy. These methods typically use hormones to prevent ovulation from occurring, keep a fertilized embryo from implanting in the uterus, or make it less likely that sperm and egg will meet.

Hormonal birth control methods include (IQWiG-b, 2017):

Birth control pills, which may include combination pills containing estrogen and progestin, or progestin-only pills

Vaginal rings like the NuvaRing

Contraceptive skin patches

Hormonal birth control shots

Implants

Theoretically, hormonal birth control may cause weight gain because the hormones used may cause bloating (from water retention), increased appetite, and increased fat storage (IQWiG-a, 2017).

Methods like birth control pills can be 91–99% effective if used correctly (Cooper, 2022). However, it’s common for people to miss pills or not take them correctly, which is why some people report getting pregnant while on the pill. Concerns about weight gain while on the pill is one reason some people stop taking the pill (IQWiG-a, 2017).

If you have concerns about birth control causing weight gain, it’s important that you find an alternative birth control method before stopping the one you are currently using. Otherwise, you risk an unwanted pregnancy.

What are the best birth control pills for losing weight?

There are no birth control methods that promote weight loss. But if you are looking for birth control that are less likely to cause weight gain, you can try non-hormonal methods. The best birth control to avoid potential weight gain includes barrier methods, non-hormonal IUDs, natural family planning, and sterilization.

There are pros and cons to each of these birth control methods. Let’s take a look at these issues in more depth.

Barrier methods

Barrier methods create barriers between sperm and eggs so that contraception can’t take place. Examples of barrier methods include (ACOG-a, 2022):

Diaphragms

Sponge

Spermicide

Cervical cap

Typically, barrier methods aren’t as efficient at preventing pregnancy as hormonal methods are, though they generally have fewer side effects. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), out of 100 people who use a barrier method to prevent pregnancy, 18–28 of them will become pregnant (ACOG-a, 2022).

You can increase your chances of preventing pregnancy by following the instructions for use carefully and using your barrier method of choice each time you have sex.

Copper IUD (Paragard)

IUDs are t-shaped devices that are inserted into the uterus and left there for an extended period, often several years. They work by reducing the chances sperm will be able to reach the egg. IUDs containing hormones also thin out the lining of the uterus so it’s less hospitable to pregnancy.

There is also a non-hormonal IUD available, made of copper, which could be a good option if you’re looking to avoid hormonal birth control. Copper IUDs like Paragard release a small amount of copper into the uterus, making the environment toxic to both sperm and eggs, thereby preventing pregnancy. Copper IUDs have the added benefit that they can be left in your body for up to 10 years (Lanzola, 2022).

Natural family planning

Although generally a less successful method of birth control, some people prefer to use natural family planning. This method uses a combination of period tracking, watching for signs of ovulation, tracking basal body temperature, and avoiding intercourse during high-risk days.

The advantage of this method is that it doesn't involve hormones or any invasive devices. It also doesn’t have side effects like weight gain. However, in practice, natural family planning has a high failure rate—about 24% of couples get pregnant while using it (Sung, 2021).

Sterilization

Sterilization involves either tubal ligation for females or vasectomy for males. These methods should only be used for couples who are sure they don’t want children or are sure that they are done having children.

Sterilization involves surgery, and although there aren’t many risks associated with these surgeries, people who have tubal ligations may be more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy in the future. Both vasectomies and tubal ligations are highly effective ways to prevent pregnancy (ACOG, 2019).

Will I gain weight after stopping birth control?

Some people notice weight changes after stopping hormonal birth control and switching to a non-hormonal method. This may be because of hormonal shifts that happen in your body after you stop taking birth control pills (Westhoff, 2007).

For instance, if birth control decreased your PMS symptoms, such as water retention, bloating, and increased hunger, you may notice these symptoms increase after you stop taking hormonal birth control pills, promoting weight gain.

Deciding which type of birth control is right for you

Choosing a birth control option that’s right for you involves weighing factors like lifestyle, current health status, how important it is for you to prevent pregnancy, and ease of use. Side effects are a consideration, too.

Although there are few research-based connections between hormonal birth control and weight gain, many people find that these methods cause weight gain, and are looking for alternatives that work well for them. If you have further questions about birth control, weight gain, and what your best options are, please contact your healthcare provider.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG-a). (2022). Barrier methods of birth control: spermicide, condom, sponge, diaphragm, and cervical cap. Retrieved from https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/barrier-methods-of-birth-control-spermicide-condom-sponge-diaphragm-and-cervical-cap

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG-b). (2022). Birth control. Retrieved from https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/birth-control

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2019). Sterilization for women and men. Retrieved from https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/sterilization-for-women-and-men

Apter, D., Zimmerman, Y., Beekman, L., et al. (2017). Estetrol combined with drospirenone: an oral contraceptive with high acceptability, user satisfaction, well-being and favourable body weight control. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care: The Official Journal of the European Society of Contraception, 22 (4), 260–267. doi:10.1080/13625187.2017.1336532. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28641030/

Cooper, D. B., Patel, P., & Mahdy, H. (2022). Oral contraceptive pills. StatPearls . Retrieved on July 11, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430882/

Gallo, M. F., Lopez, L. M., Grimes, D. A., et al. (2014). Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , 1, CD003987. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24477630/

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG-a). (2017). Contraception: do hormonal contraceptives cause weight gain? Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441582/

Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG-b). (2017). Contraception: overview . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441576/

Lanzola E. L. & Ketvertis, K. (2022). Intrauterine device. StatPearls . Retrieved on July 11, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557403/

Lopez, L. M., Ramesh, S., Chen, M., et al. (2016). Progestin-only contraceptives: effects on weight. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2016 (8), CD008815. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008815.pub4. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5034734/

Rosenberg, M. J., Waugh, M. S., & Meehan, T. E. (1995). Use and misuse of oral contraceptives: risk indicators for poor pill taking and discontinuation. Contraception , 51 (5), 283–288. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7628201/

Sung, S. & Abramovitz, A. (2021). Natural family planning. StatPearls . Retrieved on July 11, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546661/

University Health Services. (2009). Yasmin. Retrieved from https://uhs.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/Yasmin.pdf

Westhoff, C. L., Heartwell, S., Edwards, S., et al. (2007). Oral contraceptive discontinuation: do side effects matter? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology , 196 (4), 412.e1–412.e7. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1903378/