Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If you think that little spot on your face can’t be acne because you’re not in high school anymore, think again. Adult acne can happen for many reasons, but there's good news—it's treatable. Read on to learn more about adult acne and what you can do about it.

What is adult acne?

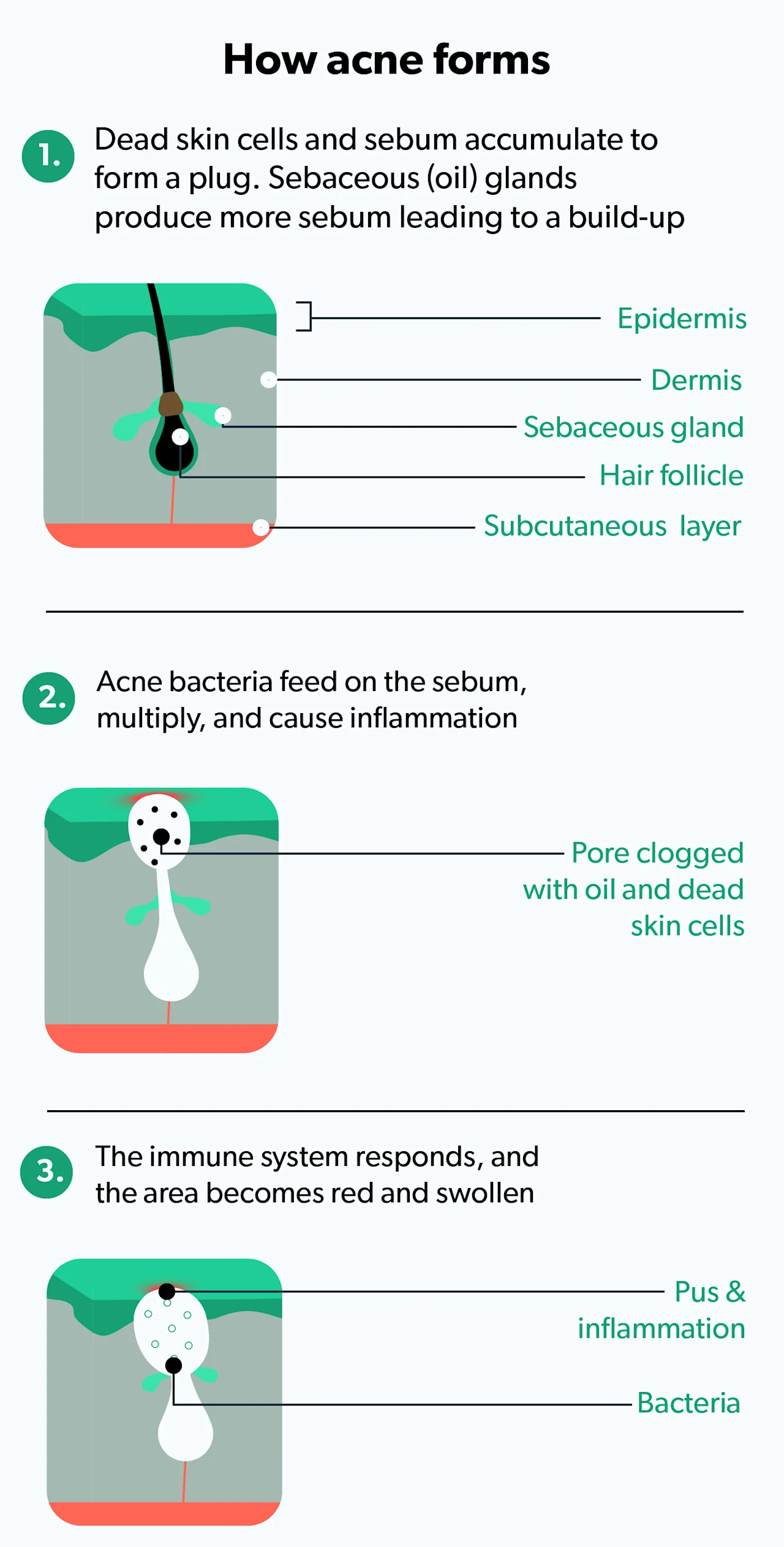

Acne is a common inflammatory skin condition where a skin pore (also called a sebaceous—i.e., oil-producing—follicle) becomes clogged with oil (sebum) and dead skin cells. This leads to inflammation. Sometimes, pimples can even become infected if accompanied by certain skin bacteria.

Acne typically affects the face, chest, back, and shoulders and can look like whiteheads, blackheads, or pimples. While typically thought of as a problem for teenagers, acne can happen at any age, even in your 30s, 40s, 50s, and beyond. According to the American Academy of Dermatology, acne is the most common skin problem in the U.S., with 40–50 million people affected at any given time (AAD, n.d.).

You can get acne for the first time as an adult (after age 20–25), a condition referred to as “adult-onset acne”; this is most commonly seen in women going through menopause. Women, in general, tend to get adult acne more often than men. Approximately 12–22% of women in the U.S. have adult acne, while only 4–6% of men do (Tanghetti, 2014).

Several factors can lead to "breakouts" of acne. Genetics, stress, lifestyle factors, and hormone imbalances can all play a role.

How is adult acne different from teen acne?

The factors leading to acne, like clogged pores and inflammation, are essentially the same for adolescents and adults. One study showed that 75% of women with acne as adults report that their acne had been with them since adolescence (Tanghetti, 2014).

However, there are some differences between adult and teen acne. For instance, adult acne is more likely to affect women, whereas adolescent acne affects both boys and girls equally (Skroza, 2018). Adult acne also tends to have more inflammatory spots and fewer whiteheads (comedones) than teenage acne (Holzmann, 2014).

Regarding timing, adult acne tends to be more chronic and longer-lasting than teen acne, which generally gets better after adolescence (Tanghetti, 2014).

Lastly, studies suggest that women with adult acne are more likely to be bothered by their acne than their teenage counterparts (Tanghetti, 2014).

Symptoms of adult acne

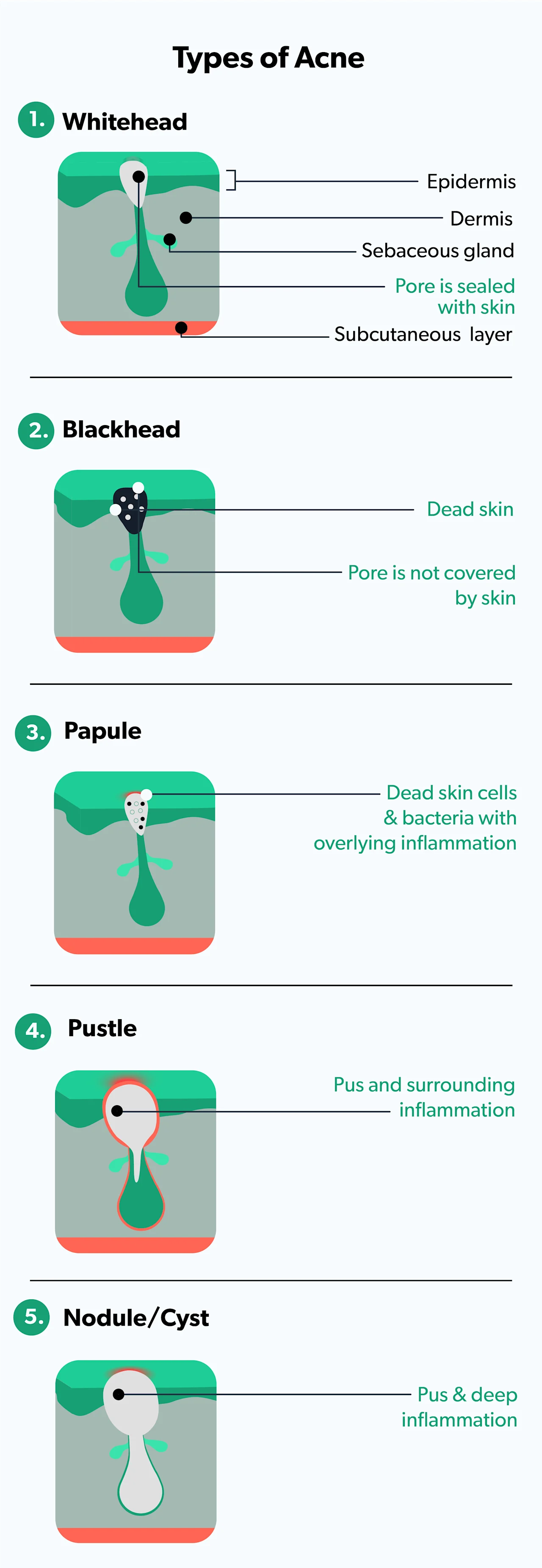

The common symptoms of the different types of adult acne are similar to teen acne and include (Sutaria, 2020):

Whiteheads: no inflammation and pore is sealed with skin (closed comedones)

Blackheads: no inflammation and pore is open (open comedones)

Papules: small amounts of inflammation

Pustules: more inflammation and pus in the pore

Nodules/cysts: deep inflammation and infection

What causes adult acne?

There are several causes of adult acne, including fluctuating hormones, stress, genetics, cosmetics, skincare habits, friction, side effects of medications, underlying medical conditions, and wearing masks (Thiboutot, 2021).

Hormones

Hormones are a significant contributor to adult acne—they are essential for the body to function normally, but it is a balancing act. If your hormone levels get off-balance, you’ll start to notice problems, like acne.

Everyone, regardless of gender, has both male hormones (androgens) and female hormones (estrogens). When androgens go up (and change the balance), they stimulate increased oil production in the skin, making you more prone to developing acne.

Women experience hormonal imbalances in the following situations:

Around their periods

During or after pregnancy

Around (or during) menopause

After starting (or stopping) birth control pills

With certain medical conditions, like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

Stress

Stress is another common culprit in adult acne. When we experience physical or emotional stress, our bodies respond with hormonal changes and increased oil production in the skin. This, in turn, leads to acne.

Stress does not generally cause acne on its own, but it can make existing acne worse. More research is needed to understand the precise role that stress plays in acne. However, the theory is that when you are stressed, your body releases hormones, like cortisol and androgens, that stimulate oil production, thereby worsening your acne.

Genetics

Perhaps you inherited oily skin or a tendency toward acne from your parents. People with excess oil are at a higher risk for acne and, for some people, acne runs in their family and they are more likely to suffer from adult acne. Studies also show that if your family members have scarring from their acne, you are at a higher risk of developing acne scars (Agrawal, 2020).

Cosmetics

Certain hair and skincare products have oil in them that can get into your skin, clog pores, and lead to acne. There is actually a medical term for this—acne cosmetica, acne caused by hair and skin products (Reszko, 2021). When shopping for cosmetics, look for items with at least one of the following terms:

Non-comedogenic

Non-acnegenic

Oil-free

Won’t clog pores

These products are less likely to cause acne. However, sleeping in any makeup can increase the risk of acne, so make sure to remove your makeup before bedtime.

Skincare habits

Skincare habits, like frequent washing or scrubbing, can strip the skin of its essential oils and lead to dry, irritated skin; irritated skin is more prone to inflammation and acne. Ideally, wash your face with a gentle cleanser when you wake up and before you go to bed. Also, avoid rubbing your face vigorously with your towel, as this can also irritate your skin and may trigger acne (Thiboutot, 2021).

Smoking

Studies suggest that smoking may play a role for some women with acne. The theory behind this is that smoking makes skin cells more sticky and more likely to clog up pores. It also triggers inflammation due to oxidative stress from the chemicals in the smoke—the combination of these effects can lead to acne (Skroza, 2018).

Friction

Pressure or friction on the skin from a helmet, bra straps, backpacks, etc., can lead to specific areas of acne. Fortunately, removing the pressure on the skin allows the acne to disappear.

Masks

With the onset of COVID-19 and the widespread use of face masks, a new potential cause of acne has come to light: mask-wearing can cause mask acne or “maskne.”

Masks can contribute to your acne problems for several reasons. Because they can dry out your skin, you should use a non-comedogenic moisturizer when wearing a mask for a prolonged time.

Makeup under your mask may clog your skin pores. Certain fabrics may irritate your skin or make it more sensitive, leading to breakouts. If not washed regularly, masks can collect dirt, germs, and dead skin cells. Lastly, if the mask does not fit well, it can cause problems—your mask should be both snug and comfortable (Techasatian, 2020).

Medications

Acne can be a side effect of some medicines, including corticosteroids, antidepressants, and anti-epileptic medications. Examples of medications known to cause acne as one of their side effects include (Kazandjieva, 2017):

Corticosteroids, like oral prednisone, inhaled steroids, topical steroid creams, etc., can accelerate acne development. They affect androgen levels and oil production.

Anabolic steroids both increase androgen levels and oil production, increasing the likelihood of developing acne.

Lithium, a drug commonly used to treat bipolar disorder, affects the skin directly. It is toxic to skin cells and triggers inflammation, leading to acne.

Other psychiatric meds like sertraline (brand name Zoloft), escitalopram oxalate (brand name Lexapro), and quetiapine (brand name Seroquel) may cause acne.

Isoniazid, a tuberculosis treatment, may cause acne.

Vitamin B6 or B12 may lead to acne.

Chemotherapy drugs, like epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors, and tumor necrosis factor-𝛼 (TNF-𝛼) antagonists, can all cause acne.

Medical conditions

Sometimes acne can be a sign of an underlying medical condition, like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a medical condition characterized by a hormonal imbalance with higher than normal levels of androgens in women. In addition to acne, women with PCOS may experience weight gain, abnormal facial hair growth, irregular periods, and infertility (Witchel, 2019).

Other medical conditions like Cushing's disease, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, androgen-producing tumors, and acromegaly can all lead to acne. If this your acne is due to an illness, once the medical condition is diagnosed and treated, the acne often resolves (Lolis, 2009).

Rosacea is another skin condition that can sometimes be confused with adult acne. Rosacea usually affects the central face (cheeks and nose) and is characterized more by persistent skin redness and flushing, rather than blackheads and pimples.

How to treat adult acne

There are many effective treatments for acne; it is important to remember that no single treatment works for everyone. And with some treatments, acne may seem like it’s getting worse before it gets better (called skin purging).

Over-the-counter treatments

People with mild acne (few pimples, whiteheads, or blackheads) can treat their acne with over-the-counter medication that contains benzoyl peroxide, salicylic acid, resorcinol, or sulfur. These can take up to 4–8 weeks to work, so don’t get frustrated if your acne does not clear up overnight.

Benzoyl peroxide and azelaic acid treat acne by attacking skin bacteria. Resorcinol, salicylic acid, and sulfur all act to help break up the whiteheads and blackheads. These medications can dry out your skin if used too frequently, so be sure to follow the instructions on the packaging.

Azelaic Acid Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

Prescription treatments

There are also prescription medications, both oral (by mouth) and topical (applied to the skin), that you can use under the guidance of your healthcare provider. Options include (Zaenglein, 2016):

Antibiotics (like doxycycline and erythromycin): These medications can decrease skin bacteria and reduce inflammation.

Birth control pills: Balancing hormonal levels in women can help decrease acne, and you should notice an improvement in 2–3 months.

Retinoids: Retinoids applied to the skin, like tretinoin, can help to break down the whiteheads and reduce inflammation. In moderate to severe acne, you may be given prescription oral retinoids, like isotretinoin (brand name Accutane), to treat your acne. However, isotretinoin CANNOT be used during pregnancy.

Spironolactone: Spironolactone blocks androgens in the skin and decreases free testosterone. However, it is not used in men because it can lead to breast enlargement.

Lasers and other light therapies: These are often used in combination with other treatments. Results vary from person to person, and many people need multiple treatment sessions.

Tretinoin Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

Natural remedies

Limited evidence exists regarding natural remedies like tea tree oil, zinc, and gluconolactone (alpha hydroxy acid) solution, but these compounds may help your acne (Zaeglein, 2016).

How to prevent adult acne

There is no fool-proof way to prevent adult acne, but there are things you can do to improve your chances of having clear skin. Think about the different causes of acne and whether they apply to you; some can be changed (like skincare habits), while others cannot (like genetics).

Check your skin and hair products to make sure that they say things like non-comedogenic, oil-free, non-acnegenic, or “won’t clog pores.”

Another way to prevent adult acne is to modify your skincare regimen. Wash your face with a gentle, non-abrasive cleanser and pat it dry every morning and evening and after sweating. Avoid allowing your skin to become too dry—use a non-acnegenic moisturizer whenever necessary. Alcohol-free cosmetics (and makeup removers) are less likely to dry out your skin.

Always remove your makeup before bedtime, and lastly, do NOT pop your pimples, as tempting as it may be.

When to see a dermatologist

Acne is frustrating at any age, but many people find adult acne especially distressing. If you have mild acne, it may improve with topical treatments purchased over-the-counter. However, if your acne is making you shy or embarrassed, is not improving, or is leaving dark spots or scars, you should see a dermatologist and talk about acne treatment options.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

American Academy of Dermatology (AAD). (n.d.). Skin conditions by the numbers. Retrieved June 3, 2021 from https://www.aad.org/media/stats-numbers

Agrawal, D. A., & Khunger, N. (2020). A morphological study of acne scarring and its relationship between severity and treatment of active acne. Journal of Cutaneous and Aesthetic Surgery , 13(3), 210–216. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_177_19. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7646434/

American Academy of Dermatology (AAD)- Are your hair products causing breakouts. (n.d.) Retrieved 5 November 2020 from https://www.aad.org/hair-care-products

Capitanio, B., Sinagra, J. L., Ottaviani, M., Bordignon, V., Amantea, A., & Picardo, M. (2009). Acne and smoking. Dermato-endocrinology , 1(3), 129–135. doi: 10.4161/derm.1.3.9638. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20436880/

Holzmann, R., & Shakery, K. (2014). Postadolescent acne in females. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology , 27 Suppl 1 , 3–8. doi: 10.1159/000354887. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24280643/

Kazandjieva, J., & Tsankov, N. (2017). Drug-induced acne. Clinics in Dermatology , 35 (2), 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.10.007. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28274352/

Lolis, M. S., Bowe, W. P., & Shalita, A. R. (2009). Acne and systemic disease. The Medical Clinics of North America , 93 (6), 1161–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.08.008. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19932324/

Reszko, A. & Berson, D. (2021). Postadolescent acne in women. In UptoDate . Owen, C. & Ofori, A.O. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/postadolescent-acne-in-women .

Skroza, N., Tolino, E., Mambrin, A., Zuber, S., Balduzzi, V., Marchesiello, A., et al. (2018). Adult acne versus adolescent acne: a retrospective study of 1,167 patients. The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology , 11 (1), 21–25. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29410726/ .

Sutaria AH, Masood S, Schlessinger J. (2020). Acne Vulgaris. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459173/ .

Tanghetti, E. A., Kawata, A. K., Daniels, S. R., Yeomans, K., Burk, C. T., & Callender, V. D. (2014). Understanding the burden of adult female acne. The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology , 7 (2), 22–30. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3935648/

Thiboutot, D., & Zaenglein, A. (2021). Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of acne vulgaris. In UptoDate . Levy, M.L, Owen, C., and Ofori, A.O. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acne-vulgaris .

Techasatian, L., Lebsing, S., Uppala, R., Thaowandee, W., Chaiyarit, J., Supakunpinyo, C., et al. (2020). The effects of the face mask on the skin underneath: a prospective survey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health , 11, 2150132720966167. doi: 10.1177/2150132720966167. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33084483/ .

Witchel, S. F., Oberfield, S. E., & Peña, A. S. (2019). Polycystic ovary syndrome: pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment with emphasis on adolescent girls. Journal of the Endocrine Society , 3 (8), 1545–1573. doi: 10.1210/js.2019-00078. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31384717/ .

Zaenglein, A., Pathy, A., Schlosser, B., Alikhan, A., Baldwin, H., & Berson, D. et al. (2016). Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. Journal Of The American Academy Of Dermatology , 74 (5), 945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26897386/ .