Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

In simple terms, priapism is an erection that lasts more than four hours and isn’t associated with any sexual stimulation. It can be painful and even dangerous if left untreated. It can occur in adults and children as young as newborns (Silberman, 2020).

While most people probably know the term from hearing it in TV commercials for erectile dysfunction drugs, it isn’t solely a side effect of medication. There are different types of priapism, and it can stem from several different conditions.

Categories of priapism

The three categories of priapism are (Levey, 2014):

Ischemic priapism or low-flow priapism

Ischemia is a medical term for insufficient blood supply to an organ. In this case, that means low blood flow through the penis. Ischemic priapism is a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment.

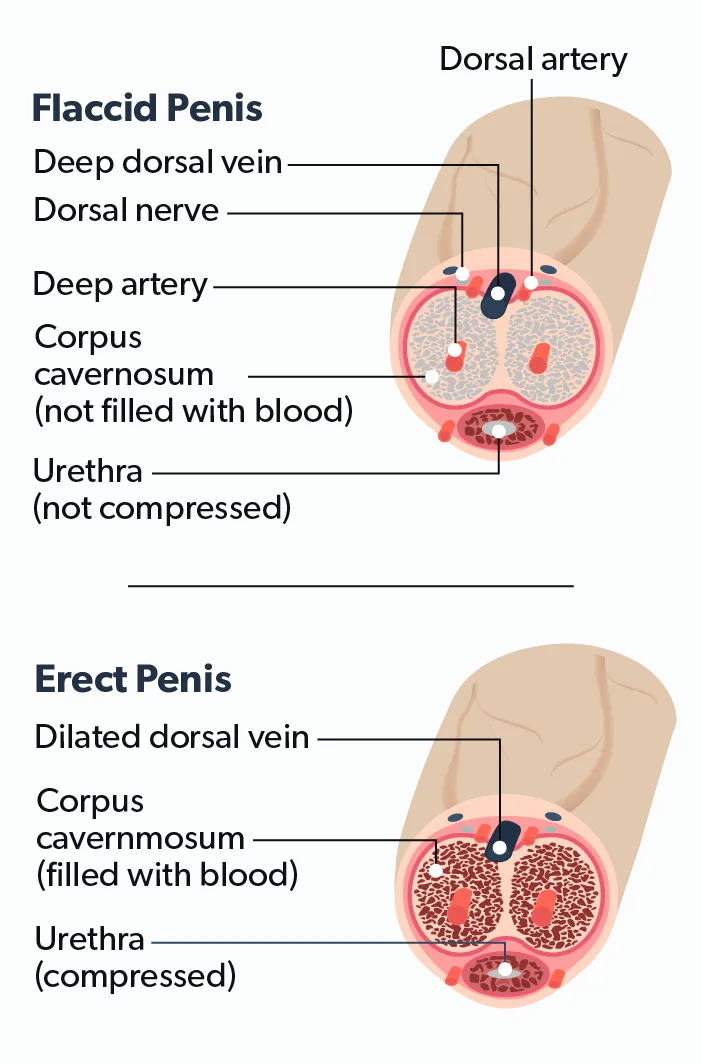

During an erection, two chambers on either side of the penis called the corpora cavernosa (singular, corpus cavernosum) fill with blood, making the penis rigid. The outflow of blood cuts off, allowing the erection to be maintained throughout sexual activity. After stimulation stops, the outflow “unlocks,” the excess blood flows out, and the erection ends. When ischemic priapism occurs, something is keeping the blood flow in that “locked” position.

Recurrent priapism or stuttering priapism

This is ischemic priapism that, as the name implies, keeps returning. Recurrent priapism is uncommon, usually experienced by men with sickle cell disease.

Non-ischemic priapism or high-flow priapism

This results from too much blood flowing through the penis. This rare type is often the result of an injury. It is usually not an emergency as there is no trapped blood in the penile chambers.

Causes of priapism

Priapism is luckily quite rare. It is estimated to occur in 0.5 to 1.5 out of every 100,000 men, and amounts to just over 5 out of every 100,000 ER visits men in the United States make each year (Roghmann, 2013).

The most common reported cause of ischemic priapism in adults is medication. Intracavernosal injections for erectile dysfunction account for about two-thirds of all cases (Silberman, 2020). Typically these medications include papaverine or phentolamine.

In rare cases, other drugs may cause priapism as a side effect. These include (Cherian, 2006):

Anticoagulants, such as warfarin or heparin

Antihypertensives

Antidepressants

Alpha-blockers

Testosterone

Medications for erectile dysfunction, such as PDE5-inhibitors

Alcohol or illicit drugs

Ischemic priapism can also be a symptom of sickle cell disease. Sickle cell anemia is the most common cause of childhood priapism cases. Other blood disorders such as leukemia, multiple myeloma, and thalassemia are also risk factors for priapism (Cherian, 2006).

Certain metabolic conditions, including diabetes and gout, may increase risk as well. Some neurological disorders are also potential causes (Cherian, 2006). There are even scorpions and spiders whose venom is known to trigger priapism (Nunes, 2013).

Non-ischemic priapism is typically caused by an injury, usually to the perineum (the area between the scrotum and the anus) or spinal cord. In these cases, the arterial inflow becomes dysregulated, and blood flows uncontrolled through the penis (Todd, 2011). There is no danger of the blood cells clotting and rarely any pain, so non-ischemic priapism is not the emergency that ischemic priapism is.

That said, there is no way to test at home what type of priapism you’re having. It’s essential to have any episode of priapism, even one that’s not painful, evaluated and treated as soon as possible. While non-ischemic priapism may not carry the risk of permanent damage, it can be a sign of more severe underlying conditions.

Treatment of priapism

Thankfully, we’ve come a long way since the days when rhubarb and leeches were the first-line treatment for priapism. For some time, healthcare providers thought that ice packs and ejaculation could help relieve cases. Evidence in support of those methods is limited, though (Song, 2013).

Most cases are treatable in the emergency department, with only an estimated 13.3% requiring further hospitalization (Roghmann, 2013). The goal is to achieve detumescence (relief of the swelling) as quickly as possible while addressing any underlying causes.

In cases of ischemic priapism, aspiration is the first step. Aspiration is drawing fluid from the body. In this case, that means pulling blood from the penile shaft with a syringe. Aspiration typically relieves about 30% of cases. If the blood trapped inside the penis has begun to clot, your provider may flush out the cavernosum with sterile saline. If aspirating does not result in relief, intracavernous injections of phenylephrine may be the next step. These injections relieve nearly all cases if administered within 12 hours of the priapism’s start (Cherian, 2006).

Some priapisms may not respond to these treatments, especially those that have gone untreated too long. In these cases, a surgical shunt is often the next step. A shunt is a small hole cut into one part of the body that allows blood or other fluids to flow into another.

For priapism, a shunt may be surgically created in the corpora cavernosa, allowing trapped blood to drain into another part of the penis. Detouring the blood to the glans (head) or spongiosum (the chamber along the base) lets it rejoin the bloodstream. In rare cases, it can require multiple shunts to resolve the problem (Cherian, 2006).

For non-ischemic priapism, one will typically remain under observation for a time, and the problem will resolve itself. If it doesn’t, a procedure to temporarily block the blood flow (embolization) or clip the blood vessel responsible closed (ligation) may be performed (Cherian, 2006).

Management of priapism

For sufferers of recurrent priapism, ongoing preventative therapy is necessary to avoid relapses. Treating the underlying cause is first and foremost. If the reason is a medication, it may only require an adjustment in dose or a switch to a different drug.

In cases where the cause is a chronic condition, such as sickle cell disease, healthcare providers have many different options. Oral medications may offer relief. For emergencies, patients can learn to use self-administered injections. In extreme cases where there is no resolution through medication, a surgically implanted penile prosthesis may be necessary (Song, 2013).

Priapism can be a sensitive subject, but it’s one to take seriously. If you ever experience priapism, it’s of the utmost importance to have it seen by a medical professional. Hoping it will just go away is risking irreversible damage and permanent erectile dysfunction. It can also be an early warning sign of a more severe condition.

If you have an erection that overstays its welcome, with or without pain, go to your nearest emergency room and follow up with your regular healthcare provider or a urologist after.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Cherian, J., Rao, A. R., Thwaini, A., Kapasi, F., Shergill, I. S., & Samman, R. (2006). Medical and surgical management of priapism. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 82 (964), 89–94. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.037291. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16461470/

Levey, H. R., Segal, R. L., & Bivalacqua, T. J. (2014). Management of priapism: An update for clinicians. Therapeutic Advances in Urology, 6 (6), 230–244. doi: 10.1177/1756287214542096. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25435917/

Nunes, K. P., Torres, F. S., Borges, M. H., Matavel, A., Pimenta, A. M. C., & De Lima, M. E. (2013). New insights on arthropod toxins that potentiate erectile function. Toxicon: Official Journal of the International Society on Toxinology, 69, 152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.03.017. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23583324/

Roghmann, F., Becker, A., Sammon, J. D., Ouerghi, M., Sun, M., Sukumar, S., Djahangirian, O., Zorn, K. C., Ghani, K. R., Gandaglia, G., Menon, M., Karakiewicz, P., Noldus, J., & Trinh, Q.-D. (2013). Incidence of priapism in emergency departments in the United States. The Journal of Urology, 190 (4), 1275–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.118. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23583536/

Silberman, M., Stormont, G., Hu, E. W. Priapism. [Updated 2020 Nov 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459178/

Song, P. H., & Moon, K. H. (2013). Priapism: Current updates in clinical management. Korean Journal of Urology, 54 (12), 816–823. doi: 10.4111/kju.2013.54.12.816. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24363861/

Todd, N. V. (2011). Priapism in acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 49 (10), 1033–1035. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.57. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21647168/