Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If you’re using an ovulation test, chances are you’re trying to get pregnant, or you’re tracking your cycle to try and avoid pregnancy.

Because ovulation tests can be helpful when trying to get—or avoid getting—pregnant, you may be wondering if ovulation tests can also detect pregnancy. The short answer is: maybe, but not reliably.

Read on to learn why your ovulation test strip might test positive if you’re pregnant but why you shouldn’t rely on it as a pregnancy test.

Will an ovulation test be positive if I’m pregnant?

If you’re pregnant, your ovulation urine test might still show a positive result. (Positive test results can look like a second test line in addition to the control line, or sometimes a smiley face.)

But, that doesn’t mean the test is looking for signs of pregnancy. Instead, it’s looking for signs that you’re ovulating. This can lead to a positive result because pregnancy hormones can look a lot like ovulation hormones.

Why might an ovulation test be positive if you’re pregnant?

Ovulation tests work by looking for high levels of a hormone called luteinizing hormone (LH).

About halfway through your menstrual cycle, your brain boosts your LH levels as a signal to your ovaries to get ready to release an egg (ovulation) (Holesh, 2021). This LH surge, which happens a few days before you ovulate, is what the ovulation test is looking for—so a positive result means that you should ovulate within the next few days (these are your “fertile days”).

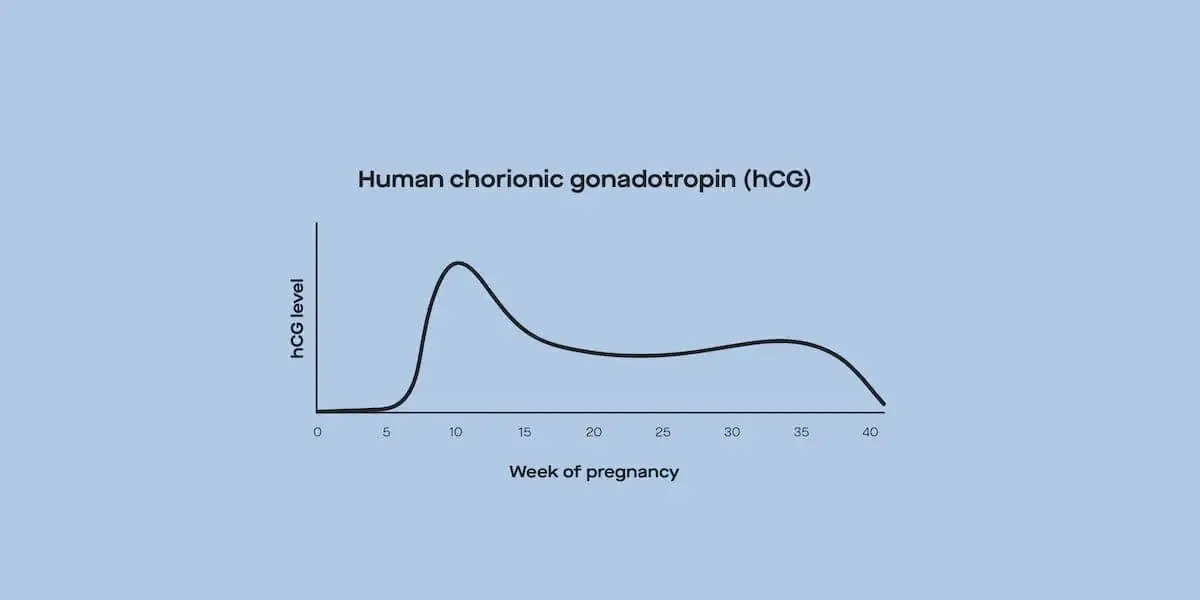

The ovulation test might also be positive when you’re pregnant because a pregnancy-specific hormone, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), behaves a lot like LH on a molecular level (Cole, 2010). And while at-home ovulation testers are great at predicting ovulation, they’re ultimately a pretty simple tool. They don’t have the kind of sensitivity it takes to distinguish LH and hCG.

So, this means that if you’re pregnant and you take an ovulation test, it might show a false positive because it’s accidentally identifying high hCG levels, not LH.

This does not mean that it’s accurately detecting your pregnancy. It is simply that the test does not always differentiate between the two hormones. However, if the test does correctly differentiate between LH and hCG—meaning that you may be pregnant, but the test is negative because LH is low and the test doesn’t recognize hCG—then, in this case, the test will show a negative result, even though you’re pregnant. These discrepancies are why ovulation tests should not be used to detect a pregnancy.

When should I use an ovulation test?

Ovulation tests are designed to be used when you aren’t pregnant (or don’t think you are). This is how they can most reliably identify the correct hormonal shifts and predict that you’re going to ovulate.

The time of the month to use an ovulation test is about halfway through your cycle (a few days before you might ovulate). Cycle length can vary from person to person, with normal cycles ranging from 21–35 days. Women with irregular cycles can use ovulation test kits, too.

And whether you have a normal or irregular cycle, it may take a few months of testing to determine when your ovulation window occurs to time testing properly (Bull, 2019). A good rule of thumb is to start testing on day 10 or 11 of your cycle (day 1 being the first day of your period) (Su, 2017).

As for what time of day is best to use an ovulation test, it’s ideal to do it in the morning. While you can take an ovulation test at any time of day, your hormones are most concentrated in your morning urine, making it easier for an ovulation test to pick up on any LH surges in your hormone levels (Su, 2017).

When should I use a pregnancy test?

If you have any reason to think you might be pregnant—whether you’re actively trying to get pregnant, you had unprotected sex, you were late taking your birth control, or you missed your period—taking a pregnancy test is a good idea.

How long after a positive test do I ovulate?

Ovulation will generally occur within 48 hours of a positive ovulation test.

Remember that everyone’s cycle is different, and a test showing an LH surge does not guarantee that you’ll ovulate. Even so, studies have shown a high level of accuracy for urinary ovulation tests identifying the LH surge that comes about 48 hours before ovulation (Su, 2017).

How do I track ovulation?

You can track your ovulation—and predict your fertile window, or the time that it’s most likely you’ll get pregnant—using cues from your body as well as ovulation tests, including:

Cervical mucus consistency: When you ovulate, your cervical mucus (it comes out like discharge in your underwear) becomes clear, slippery, and stretchy—kind of like raw egg whites. It’s one of your body’s ways of welcoming any nearby sperm and making their journey to the egg easier (Ecochard, 2015).

Basal body temperature (BBT): Your body temperature stays about the same all month, except for right before you ovulate (when it dips slightly) and right after you ovulate (when it spikes). If you take your temperature daily right when you wake up and before you do anything, you can start to track what day of your cycle your temperature shifts usually happen, which may help you predict ovulation next month (Steward, 2021).

How do I know if I’m pregnant?

The best way to know if you’re pregnant is by taking a pregnancy test. At-home pregnancy tests are widely available over the counter or online.

It may feel excessive—not to mention expensive—to get two kinds of tests, but using tests for the purpose they’re designed for is the best way to get the most accurate and reliable results. So, use an ovulation predictor kit when you’re trying to figure out when you’re ovulating to achieve (or avoid) pregnancy, and use a pregnancy test if you think you might be pregnant.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Bull, J., Scherwitzl, E. B., Scherwitzl, R., et al. (2019). Real-world menstrual cycle characteristics of more than 600,000 menstrual cycles. NPJ Digital Medicine, 2 (83). doi:10.1038/s41746-019-0152-7. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-019-0152-7

Cole, L. A. (2010). Biological functions of hCG and hCG-related molecules. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 8 , 102. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-8-102. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2936313/

Ecochard, R., Duterque, O., Leiva, R., et al. (2015). Self-identification of the clinical fertile window and the ovulation period. Fertility and Sterility, 103 (5), 1319–25.e3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.031. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0015028215000783

Holesh, J. E., Bass, A. N., & Lord, M. (2021). Physiology, ovulation. StatPearls . Retrieved on May 5, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441996/

Steward, K. (2021). Physiology, ovulation and basal body temperature. StatPearls . Retrieved on May 5, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546686/

Su, H. W., Yi, Y. C., Wei, T. Y., et al. (2017). Detection of ovulation, a review of currently available methods. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine, 2 (3), 238–246. doi:10.1002/btm2.10058. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5689497/