Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Klinefelter syndrome is a genetic condition that affects males by causing them to be born with one or more extra X chromosomes. The main effect of Klinefelter syndrome is abnormal growth and development of the testicles (testes). This abnormal growth can cause infertility, as well as weak bones and other medical conditions related to hormone-related imbalances. The syndrome can also affect the way a male’s body develops (Kanakis, 2018).

What is Klinefelter syndrome?

Human DNA is packaged inside of 23 pairs of chromosomes. Two of these chromosomes are known as the sex chromosomes because they help to determine a person’s biological sex (Snell, 2018).

Typically, females have two X chromosomes, while males have one X and one Y chromosome. But males born with Klinefelter syndrome have an extra copy of the X chromosome, or sometimes multiple extra X chromosomes. In other words, rather than having an XY chromosome pair, they have XXY, XXXY, or some other combination of extra sex chromosomes.

In 85% of cases, people with Klinefelter syndrome are born with one additional X chromosome. In the remaining 15% of cases, they may be born with two or more additional sex chromosomes (Shiraishi, 2018).

How common is Klinefelter syndrome?

The syndrome seems to be relatively common compared to other chromosome disorders. About 1 in 650 newborn males have it. That said, some experts suspect that many people with Klinefelter syndrome are never diagnosed—because their symptoms are very mild—so the true prevalence may be much higher (Kanakis, 2018).

What causes Klinefelter syndrome?

Experts understand that, at a genetic level, the syndrome is caused by something known as nondisjunction. This is when chromosomes fail to split apart as usual. But experts consider this to be “random,” meaning there’s no explanation for why it happens (Los, 2021).

Klinefelter syndrome symptoms

Many people with Klinefelter syndrome are not diagnosed until after puberty because the symptoms usually do not appear before then. However, there are prenatal screenings that healthcare providers can conduct to catch the condition early. Still, many people with the syndrome may not know they have it because their symptoms are mild or unnoticeable (Kanakis, 2018).

Those with symptoms will typically have firm, small testes that do not produce or release enough testosterone into the bloodstream, also known as hypogonadism. As a result, those with this condition tend to have (Kanakis, 2017; Los, 2021):

Long legs and short torsos

Enlarged breasts (gynecomastia)

Reduced muscle tone

Little facial or body hair

Infertility due to unhealthy or immotile (unable to move or swim) sperm

Hypospadias: a condition where the urethra opening is on the underside of the penis

Along with these developmental and reproductive symptoms, Klinefelter syndrome can lead to changes in how a person’s brain forms and develops. As a result, the syndrome is associated with a higher risk of learning disabilities or deficits related to verbal processing, social interaction, and attention. Because of this, people with Klinefelter syndrome may be more likely to struggle in school and in the workplace. Some research has found that people with the syndrome may also be more prone to anxiety and depression (Skakkebæk, 2018).

Klinefelter syndrome diagnosis

Because Klinefelter syndrome is a genetic condition, its diagnosis almost always involves genomic or genetic testing, such as a DNA or chromosome analysis. This is usually done by examining blood samples collected prenatally (before birth) or much later in life—such as after puberty.

Several analysis techniques—including a blood test called a karyotype analysis that checks for things like extra chromosomes—can conclusively determine if a person has Klinefelter syndrome (Los, 2021).

Klinefelter syndrome treatment

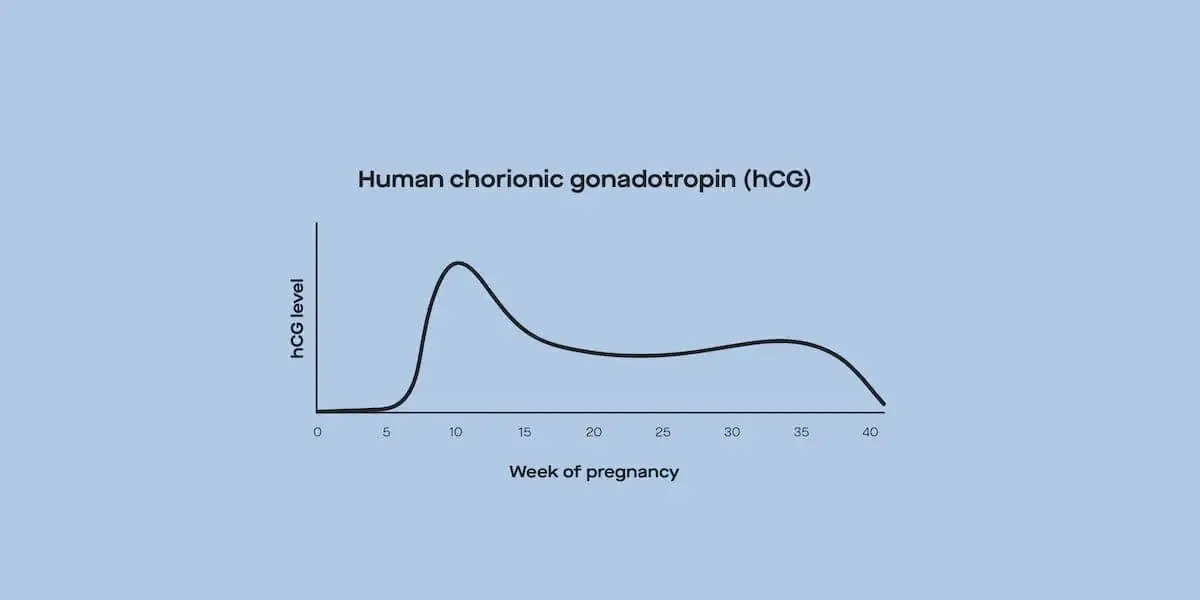

The most common treatment for Klinefelter syndrome is hormone replacement therapy—and specific testosterone replacement therapy (TRT)—to bring hormone levels closer to normal thresholds. This treatment is often led by an endocrinologist, a doctor specializing in hormone-related disorders. TRT can help prevent the physical symptoms of the syndrome, and can also prevent fertility-related challenges (Los, 2021).

In some cases, prenatal screening identifies the syndrome before a male is born, so some forms of hormone replacement therapy may start during infancy. This early treatment may prevent some of the heart, brain, or other developmental abnormalities that may lead to later symptoms or challenges.

But in many cases, testosterone replacement therapy does not begin until puberty or beyond—when the more noticeable symptoms of the condition often emerge (Kanakis, 2018).

Klinefelter syndrome life expectancy and complications

While Klinefelter syndrome is not deadly, people with it are at higher risk for several diseases and premature death (Gravholt, 2018).

Because this syndrome can affect how one’s body develops and how much testosterone it produces, there are several diseases that you and your healthcare provider should look out for.

These include (Bearelly, 2019; Gravholt, 2018):

Reduced bone mineral density and osteoporosis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Obesity and type 2 diabetes

Breast cancer

Autoimmune disorders or autoimmune diseases (although the links here are uncertain)

Due to these health complications, some research has found that people with Klinefelter syndrome live an average of 2.1 years less than those without the syndrome (Kanakis, 2018).

While these complications can sound scary, it’s important to remember that Klinefelter syndrome is often mild—and even when its effects are more pronounced, there are good treatments available.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Bearelly, P. & Oates, R. (2019). Recent advances in managing and understanding Klinefelter syndrome. F1000Research , 8 , F1000 Faculty Rev-112. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16747.1. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6352920/

Gravholt, C. H., Chang, S., Wallentin, M., Fedder, J., Moore, P., & Skakkebæk, A. (2018). Klinefelter Syndrome: Integrating Genetics, Neuropsychology, and Endocrinology. Endocrine Reviews , 39 (4), 389–423. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00212. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/39/4/389/4847830

Kanakis, G. A. & Nieschlag, E. (2018). Klinefelter syndrome: more than hypogonadism. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental , 86 , 135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.09.017. Retrieved from https://genetic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Kanakis-and-Nieschlag.-2018.-Klinefleter.more-than-just-hypogonadism.pdf

Los, E. & Ford, G. A. (2021). Klinefelter Syndrome. [Updated July 25, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482314/

Shiraishi, K., & Matsuyama, H. (2018). Klinefelter syndrome: From pediatrics to geriatrics. Reproductive Medicine and Biology , 18 (2), 140–150. doi: org/10.1002/rmb2.12261. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/rmb2.12261

Skakkebæk, A. & Moore, P. J. (2018). Anxiety and depression in Klinefelter syndrome: The impact of personality and social engagement. PloS one , 13(11), e0206932. Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206932. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30412595/

Snell, D. M. & Turner, J. (2018). Sex Chromosome Effects on Male-Female Differences in Mammals. Current Biology : CB , 28 (22), R1313–R1324. doi: org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.09.018. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982218312132