Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Sperm are reproductive cells that are found in a man’s ejaculate. Pregnancy can only happen if one of those sperm successfully fertilizes the egg in a woman’s reproductive tract.

But how do they get to the egg? Do they really “swim”? And how do you know if your sperm are healthy? This article answers all of those questions and more.

What is sperm?

Sperm is short for spermatozoa. Each spermatozoon is made up of a single cell, which contains a man’s genetic material, or DNA. That single sperm cell has a tail, or flagellum, which allows the sperm to move or “swim” (Cao, 2018).

Sperm vs. semen

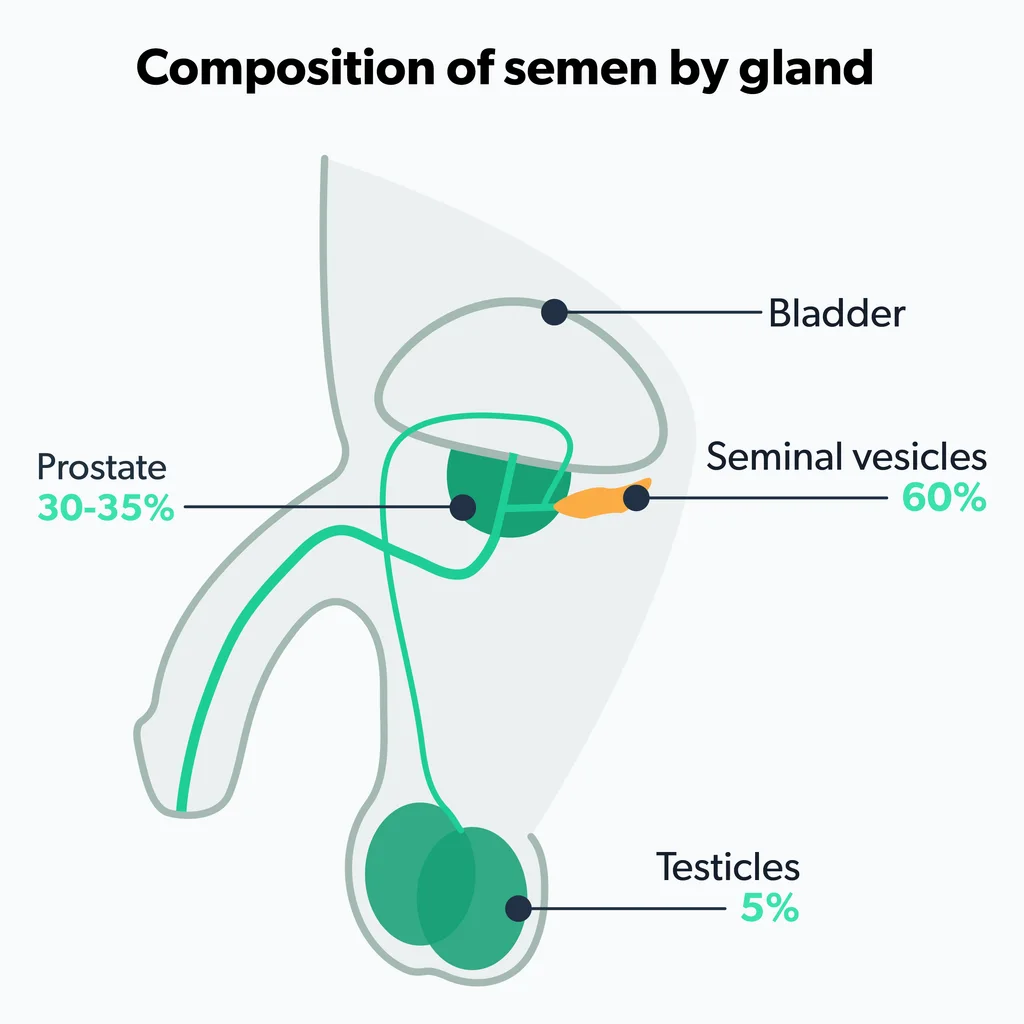

Some people confuse the terms sperm and semen. Semen is ejaculate. It contains sperm. It also contains proteins and secretions from the prostate and other parts of the male reproductive system. Together, all of this is known as the seminal fluid.

Put another way, when a male ejaculates, semen is the liquid that comes out. That liquid contains sperm (Sunder, 2021).

There are some cases when semen contains no sperm. This is a condition called azoospermia, and it affects about 10–15% of men with infertility (Wosnitzer, 2014).

What does sperm look like?

Sperm are composed of a “head” and “tail.”

The head is shaped more or less like a sunflower seed. The tail, or flagellum, begins with a thicker “midpiece” and then tapers to a point. Imagine a sunflower seed with a thin mouse-like tail, and you’ve got the general idea (Dcunha, 2022).

How is sperm produced?

The testicles are not only important for producing testosterone, a sex hormone that affects sexual development and reproduction, they also play a major role in sperm production or spermatogenesis.

Spermatogenesis takes place inside small tubes within the testicles called the seminiferous tubules. A man’s testicles are basically sperm factories (Dcunha, 2022).

Where is sperm stored?

After they’re made, sperm move out of the testicles and into the epididymis. The epididymis is a structure located inside a man’s scrotum and on the tops and backs of each of his testicles. The sperm mature inside the epididymis, which stores them until they’re released in ejaculate during an orgasm (Dcunha, 2022).

How long does sperm live?

How long sperm is viable after ejaculation depends on the circumstances. Sperm can live anywhere from a few minutes to a week, depending on where the ejaculate goes.

Once ejaculated into a partner’s reproductive tract, some will die within a matter of minutes or hours. However, those that do survive can live inside a woman’s reproductive tract for up to five days and fertilize an egg (Bibov, 2018).

While there isn't a lot of research around this question, sperm is pretty sensitive and cannot survive for long once they are exposed to the air and temperatures changes outside of the body. Sperm can be preserved for decades when semen is frozen and stored. The sperm can be thawed and used in the future for various procedures (Sacha, 2021).

In some cases, sperm are not viable before ejaculation even occurs. Semen analyses have found that, on average, about 60% of the sperm in a man’s ejaculate are intact and alive, meaning the rest are not viable (Sunder, 2021).

Sperm’s role in fertility

Sperm’s role in male fertility is essential. Without sperm, conception (pregnancy) isn’t possible.

During ovulation, a female’s reproductive system releases one mature egg (or oocyte) from the ovaries. That egg travels into a structure called a fallopian tube, where a sperm can fertilize it. If fertilization happens, the fertilized egg, called a zygote, moves into the uterus (Rosner, 2021).

During sexual intercourse and ejaculation, millions of sperm are released into the female reproductive tract. On average, a man’s ejaculate contains 39 million sperm or more. But again, a lot of those sperm are already dead.

Among the sperm that are still alive, their motility—or ability to move—as well as their morphology (shape) help determine whether they’re healthy sperm that can survive and “swim” up to the uterus to fertilize the egg (Sunder, 2021). Healthy sperm should propel themselves forward to find and penetrate an egg, but sometimes, sperm don’t move the way they should. If a sperm is sluggish or doesn’t move at all, it’s called asthenospermia or asthenozoospermia (Elia, 2010).

If a couple has fertility challenges and has to rely on fertility methods like assisted reproductive technology (ART), sperm are essential. For example, during in vitro fertilization (IVF), a form of ART, a male’s sperm is used to fertilize a female’s egg in a lab setting. This fertilized egg is then implanted in the female’s uterus (Choe, 2021).

How to determine if sperm are healthy

If a couple has fertility-related challenges, the male may undergo something called a semen analysis. This is a type of laboratory test that examines semen and sperm quality to check for male infertility (Sunder, 2021).

A semen analysis looks at many different aspects of a man’s semen. These include:

Number of sperm

Sperm concentration

Volume of ejaculated fluid

Composition of ejaculated fluid

Sperm viability (how healthy they are)

Sperm morphology (the size and shape of sperm)

Sperm motility (how well they move or “swim”)

All of these factors play a role in male fertility. However, if the analysis shows that some of these factors fall below the “normal” ranges, that doesn’t automatically mean someone has infertility. And even if the sperm are not capable of fertilizing a partner’s egg following intercourse, other fertility methods (such as IVF) are still possible.

How do I make my sperm healthier?

There are a number of activities or habits that are linked with healthier sperm. Here are things you can do if you want to increase your sperm count and overall sperm health (Sunder, 2021):

Don’t smoke

Reduce your alcohol intake

Exercise (Gaskins, 2015)

Eat a healthy diet that includes fruits and vegetables

Lose weight if you have obesity

Avoid spending a lot of time in hot environments, such as hot tubs or saunas

And, if you’re curious about the health of your sperm, you can always ask your healthcare provider if they think a semen analysis, either at a clinic or using a home test kit, is right for you.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Bibov, M. (2018). Role of the reactive oxygen species induced DNA damage in human spermatozoa dysfunction. AME Medical Journal. doi:10.21037/amj.2018.01.06. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20190225074130id_/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6aba/2b1355f34565f43e9f8adf03390d96d9e160.pdf

Cao, X., Cui, Y., Zhang, X., et al. (2018). Proteomic profile of human spermatozoa in healthy and asthenozoospermic individuals. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology : RB&E , 16 (1), 16. doi:10.1186/s12958-018-0334-1. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12958-018-0334-1

Choe, J., Archer, J. S., & Shanks, A. L. (2021). In Vitro Fertilization. StatPearls . Retrieved Apr. 12, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562266/

Dcunha, R., Hussein, R. S., Ananda, H., et al. (2022). Current Insights and Latest Updates in Sperm Motility and Associated Applications in Assisted Reproduction. Reproductive Sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif.) , 29 (1), 7–25. doi:10.1007/s43032-020-00408-y. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43032-020-00408-y

Elia, J., Imbrogno, N., Delfino, M., et al. (2010). The Importance of the Sperm Motility Classes - Future Directions. The Open Andrology Journal, 2 , 42–43. Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Importance-of-the-Sperm-Motility-Classes-Future-Elia-Imbrogno/513261ae0a11d524921f0ef642516117c8aebaeb#paper-header

Gaskins, A. J., Mendiola, J., Afeiche, M., et al. (2015). Physical activity and television watching in relation to semen quality in young men. British Journal of Sports Medicine , 49 (4), 265–270. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091644. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3868632/

Rosner, J., Samardzic, T., & Sarao, M. S. (2021). Physiology, Female Reproduction. StatPearls . Retrieved Apr. 12, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537132/

Sacha, C. R., Vagios, S., Hammer, K., et al. (2021). The effect of semen collection location and time to processing on sperm parameters and early IVF/ICSI outcomes. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics , 38 (6), 1449–1457. doi:10.1007/s10815-021-02128-x. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10815-021-02128-x

Sunder, M. & Leslie, S. W. (2021). Semen Analysis. StatPearls . Retrieved Apr. 12, 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564369/

Wosnitzer, M., Goldstein, M., & Hardy, M. P. (2014). Review of azoospermia. Spermatogenesis, 4 (1). doi:10.4161/spmg.28218. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4124057/