Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

When you’re taking an essential medication for your health, the last thing you want to worry about is taking another medication that might not mix well with that drug. ARVs (antiretroviral drugs) are an excellent example of medications you need to be extra careful with—after all, you’re taking ARVs to keep your HIV under control. That’s pretty important. But what if you have erectile dysfunction (ED), too? That’s a common condition for men with HIV. Can you take sildenafil (Viagra) to treat your ED without worrying about how it will impact your ARVs?

Let’s take a look at how these drugs interact.

Sildenafil interactions with ARVs

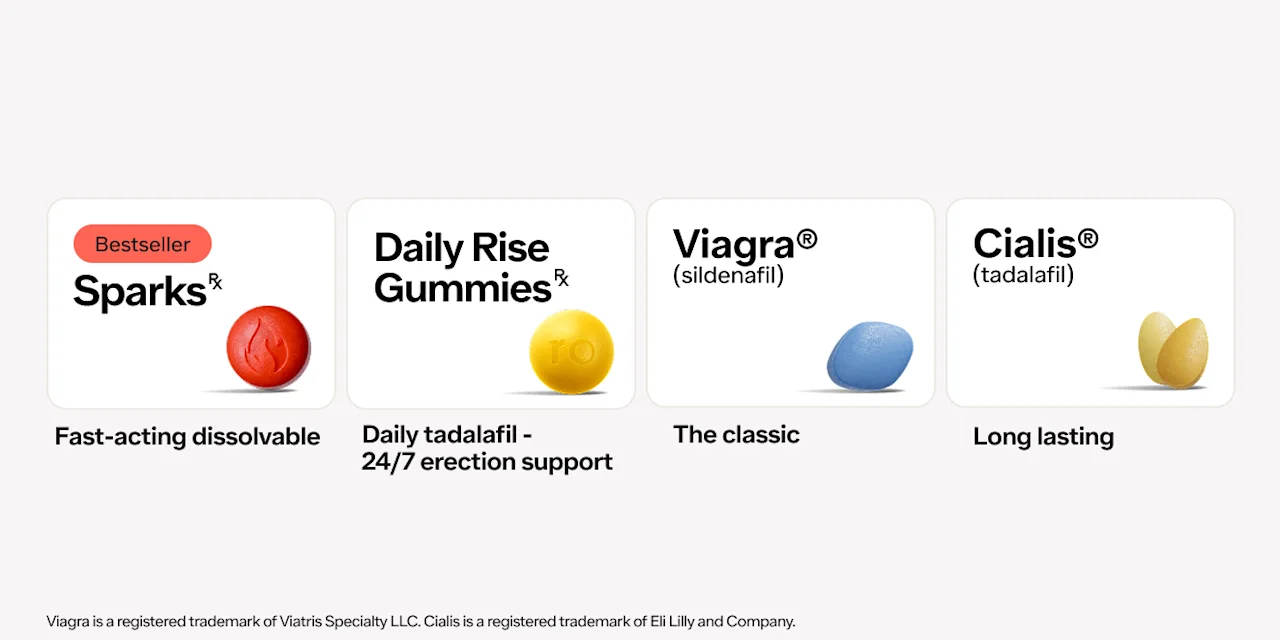

Sildenafil (brand name Viagra) is an oral medication for ED (erectile dysfunction) and part of a class of medications known as PDE5 inhibitors; these include vardenafil (brand names Levitra, Staxyn), tadalafil (brand name Cialis), and avanafil (brand name Stendra). These drugs help the blood vessels in your penis to open up, allowing blood to flow in and produce an erection when you’re sexually stimulated.

ARVs are drugs that keep levels of HIV (a retrovirus) in the blood low by stopping or slowing HIV’s normal replication cycle. It’s not a cure, but it can help HIV-positive individuals lead normal lives with normal life expectancies.

Since erectile dysfunction is common among HIV-infected men, it’s important to know if combining these drugs is safe (Crum-Cianflone, 2007).

Can I take sildenafil with my ARVs?

Problems can occur if you take sildenafil certain HIV medications. To avoid potentially dangerous drug interactions, it's always important to tell your healthcare provider what medications you’re currently taking, including prescription and over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and herbal supplements.

When you talk to your healthcare provider about starting Viagra or another PDE-5 inhibitor, it's especially important to let them know if you're taking any medications for the treatment of HIV, including (AETC, n.d.):

Delavirdine (Rescriptor)

Amprenavir (Agenerase)

Indinavir (Crixivan)

Ritonavir (Norvir)

Saquinavir (Fortovase, Invirase)

Elvitegravir/cobicistat/TDF/FTC (Stribild)

Fosamprenavir (Lexiva)

Atazanavir (Reyataz)

Darunavir (Prezista)

Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra)

Nelfinavir (Viracept)

Certain ARVs, especially those listed above, have the potential to increase the concentration of sildenafil in your body, which can make it more likely that you experience common Viagra side effects, such as headache, low blood pressure, and flushing. If you take any of these HIV medications, your healthcare provider may start you on a lower Viagra dosage, decrease your Viagra dosage, or recommend that you take Viagra less frequently, like every other day.

Some HIV medications, like etravirine (Intelence), may also lower the concentration of Viagra in the body, so your healthcare provider may adjust your dose depending on how effective Viagra is for you (OARAC, 2021).

Other HIV medications not listed above may also have interactions with sildenafil, so be sure to discuss all your medications with your healthcare provider.

Potential side effects of Viagra

Common side effects of Viagra include dizziness, headache, flushing, upset stomach or indigestion, increased sensitivity to light, blurred vision, a stuffy or runny nose, back pain, insomnia, rash, and muscle pain (Dhaliwal, 2020).

Less common side effects of Viagra include priapism (a prolonged erection that won't go away), and ringing in the ears, or hearing loss. If you experience any of those, seek medical advice right away.

If you’re taking ARVs, talk to your healthcare provider about how Viagra may affect you, and always follow your healthcare provider’s dosing instructions. Viagra isn’t safe for everyone. People who take certain drugs, including ARVs, or have certain health conditions, like liver or kidney disease, may need to adjust their Viagra dose in order to take Viagra safely.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Viagra Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

Cialis Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

AIDS Education and Training Center (AETC). (n.d.). Recreational Drugs and HIV Antiretrovirals Retrieved from https://aidsetc.org/sites/default/files/resources_files/2014_Recreational Drug Interaction Guide.pdf

AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC). (2021). Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV . Retrieved from https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf

Crum-Cianflone, N. F (2007). Erectile dysfunction and hypogonadism among men with HIV . AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21 (1), 9–19. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0071. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17263654/

Dhaliwal, A. & Gupta, M. (2020). PDE5 inhibitor. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Dec. 14, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549843/