Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If you’ve ever eaten something and developed heartburn soon afterward, you’ve already made the connection between your diet and acid reflux. If you experience this a lot, you may wonder which foods to eat and which to avoid to help your symptoms. Sometimes, a combination of dietary changes and lifestyle modifications may help control or completely relieve your symptoms.

Acid reflux: what is it?

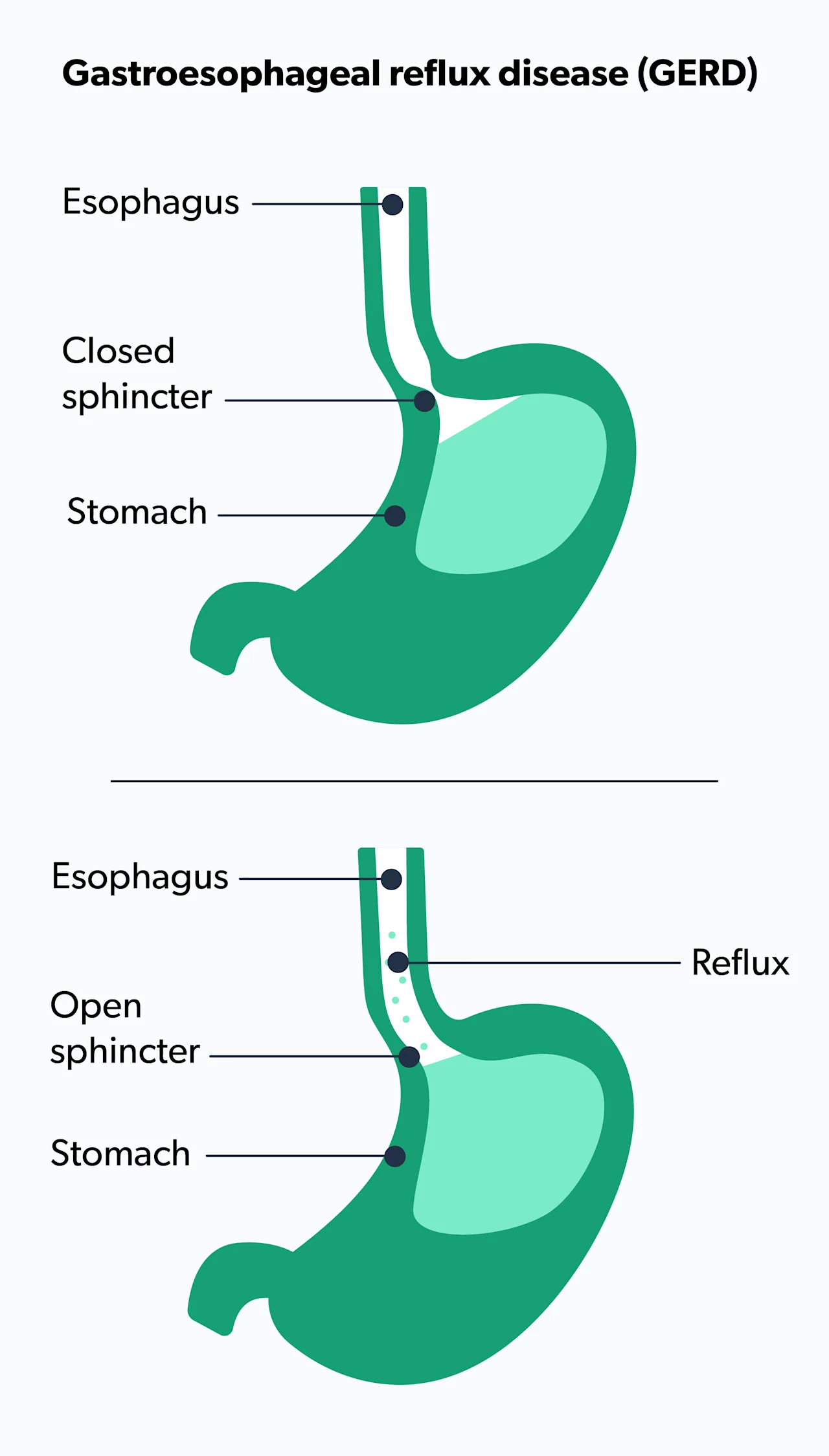

Acid reflux happens when stomach acid flows back or regurgitates up into the esophagus. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is the muscle at the end of the esophagus where it connects to the stomach. When the LES functions normally, it closes to prevent any stomach acid regurgitation. If the LES muscle is weak or there is a lot of intra-abdominal pressure, you can have acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (Antunes, 2021).

About 20% of people have this condition. Most have mild to moderate acid reflux, but some people may have more severe discomfort or even complications (Antunes, 2021).

One of the symptoms of acid reflux is heartburn or indigestion, a burning sensation that occurs in the chest, behind the breastbone. It can last for hours and can be very uncomfortable. Some people may have other symptoms, including abdominal bloating, nausea, dry cough, hoarseness, and a sore throat (Antunes, 2021).

If you have diabetes, it’s important to know that people with diabetes may be more prone to acid reflux and GERD. There are several reasons for this. People with diabetes may have neuropathy or nerve damage that affects the LES and allows for more acid reflux and regurgitation. Some people with diabetes may develop gastroparesis—when it takes longer for food to move through the digestive tract. Slower transit time keeps the stomach acid in the stomach for a longer time, allowing much more acid reflux to regurgitate instead of moving through the intestines (Ha, 2016).

Many people with diabetes may also have obesity and have hiatal hernias, a situation in which part of the stomach slips up through the diaphragm and makes it easier to have reflux. People with obesity have a greater risk of GERD, as the extra intra-abdominal pressure weakens the strength of the LES. Acid reflux dietary changes or a GERD diet and some lifestyle changes might be even more critical for you to do if you have diabetes (Ha, 2016).

What can I do before changing my diet?

There are several over-the-counter and prescription medications to treat GERD and acid reflux. Most healthcare professionals will advise you to make lifestyle changes first and see if that helps alleviate the troublesome symptoms without any pills or liquids.

Lifestyle tweaks to help with acid reflux symptoms include (Sethi, 2017):

Stop wearing tight clothing.

Eat small meals and eat them slowly.

Stop eating three to four hours before bed.

Don’t lie down after eating for a nap—stay upright for at least two hours after eating.

Stop chewing gum, especially peppermint or spearmint gum.

Try to lose some weight if you are overweight.

Stop tobacco products.

Stop drinking alcohol.

Raise the head of your bed by four to six inches to keep your head elevated.

Take antacids if you need them.

Certain medications can cause acid reflux or GERD. These include some common over-the-counter medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like Advil, antihistamines, and vitamin C. Some prescription drugs, including antibiotics, nitrates, calcium channel blockers, steroids, and statins, may also cause GERD. You may want to speak to a healthcare professional to change your prescription or over-the-counter medications to help alleviate your acid reflux symptoms (MacFarlane, 2018).

However, if you take antidepressants, there is some evidence that they can help reduce GERD and symptoms of acid reflux. A well-regarded study found people with heartburn and GERD reduced their symptoms significantly when they took their prescribed antidepressants regularly. Those with esophageal pain saw a moderate decrease in discomfort. Some healthcare professionals may recommend taking antidepressants to help with acid reflux symptoms and GERD (Weijenborg, 2015).

Foods to avoid

Some of these foods may seem obvious, as they are generally regarded as “unhealthy,” but some may seem counterintuitive. Certain foods can increase acid reflux, even if they are otherwise good for you. If you have frequent heartburn or indigestion, you may consider decreasing or eliminating these foods from your diet, even if they are considered healthy.

Here are common foods that cause acid reflux (Surdea-Blaga, 2019).

Caffeine

You may start your day with a cup of coffee, tea, or hot cocoa—all of which contain caffeine. Caffeine has several mechanisms of action that increase acid reflux. Caffeine irritates the lining of the stomach and esophagus. The naturally high acidity found in coffee and tea can also increase the amount of acid refluxing into your esophagus. Coffee, tea, and cocoa contain a substance that relaxes smooth muscle. As such, they may relax and open the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing more acid to regurgitate.

Chocolate

This is another delicious food that can increase acid reflux. Chocolate also contains a substance that relaxes all of your body’s smooth muscles, including your lower esophageal sphincter. This relaxing effect is part of why chocolate makes us feel so good, but it can also increase acid reflux.

Citrus fruits

Citrus fruits have a lot of vitamin C and add a lot of brightening flavor to your food and drink. Certain citrus fruits can cause acid reflux because of their high acidity. These include grapefruit, lemon, lime, and oranges.

Dairy products

You may be drinking or eating dairy products for the health benefits of calcium and vitamin D. However, full-fat dairy like whole milk can cause acid reflux because certain fats increase stomach acid production. You can enjoy low-fat or fat-free versions of milk, cheese, sour cream, yogurt, and even ice cream, and potentially see improvement in your acid reflux symptoms.

Fizzy drinks

Soda is full of acid, but even if you drink zero-calorie carbonated drinks like flavored seltzer to increase your water intake, you may be increasing your chances of acid reflux. Almost all carbonated drinks are acidic, which can worsen acid reflux. Also, the bubbles in carbonated beverages cause bloating, which can increase your discomfort.

Fried foods

Fatty foods make your digestive system work harder, and certain fats aggravate and increase stomach acid production. Fried foods are one of the worst things to eat if you have acid reflux. Most fast foods, like french fries, onion rings, and cheeseburgers, are fried. Not only do they cause indigestion and heartburn, but they can also cause weight gain, which may further increase reflux.

Garlic and spicy foods

Although garlic is considered healthy, and some find it absolutely delicious, many people have symptoms of acid reflux like heartburn, nausea, burping, and bloating right after eating it. Garlic can irritate the esophagus and the stomach, as well as increase stomach acid production. Some people have these reactions to onions or spicy foods as well.

High-fat foods

Certain fats exacerbate stomach acid. Avoid or limit fatty meats like lamb, pork, bacon, and beef. Try to limit greasy foods, creamy dressings, sauces, or gravies, and processed foods. Some desserts may have a high-fat content. Reserve these for a special occasion.

Mint

Peppermint and spearmint are refreshing, but just like chocolate, these mints contain a substance that helps relax the body's smooth muscles. Interestingly, peppermint is used in stomach soothing herbal teas for its relaxing properties, but it can increase acid reflux.

Salty foods

Some studies say salty food can increase acid reflux symptoms. Scientists are researching the exact cause. If you are sensitive to salt, you may want to try a low-salt diet and see if that reduces your acid reflux symptoms (Shibata, 2015).

Tomatoes

You may be eating tomatoes for their high levels of vitamin C and lycopene. Like citrus fruits, though, tomatoes have high acidity. Even when cooked, tomatoes can exacerbate acid reflux symptoms from increased stomach acid. You may want to limit or avoid eating tomatoes, including raw tomatoes, salsa, or anything cooked with tomato sauce, including pizza, meatballs, or chili (Salehi, 2019).

Alcohol

Many healthcare professionals recommend limiting or avoiding alcohol if you suffer from acid reflux or GERD. Some studies show alcohol itself can irritate the lining of the esophagus and stomach. Other studies show that alcohol weakens the strength of the lower esophageal sphincter. Some people may be sensitive to alcohol's effect on their digestive system, and this can cause other gastrointestinal issues in conjunction with acid reflux (Pan, 2019).

Foods to eat

While the list of reflux-worsening foods above might seem pretty long, there are plenty of similar foods you may be able to swap in and avoid symptoms of GERD (Newberry, 2019):

Noncitrus fruits do not have acid to trigger acid reflux symptoms. These include apples, bananas, berries, melons, and pears.

Healthy fats, including olive oil, sunflower, or sesame oil, can help. You can also add avocado, flaxseed, or walnuts to your diet.

Healthy complex carbohydrates, including steel-cut oatmeal, brown rice, and whole grains, are also helpful for acid reflux. There is current research into the effects of high-fiber on acid reflux.

Lean meats and other low-fat, high-protein sources, including fish, seafood, chicken, and turkey, are good additions to your diet.

Vegetables are low fat and low sugar and can help decrease stomach acid production. Almost all vegetables are fine, except for tomatoes (technically, a fruit), which contain acid (Zhang, 2021).

Herbal products for acid reflux

Your grandmother or herbalist may have told you to drink tea to calm your stomach and relieve indigestion. Avoid tea with caffeine and mint teas, as they increase acid reflux symptoms. There is anecdotal but very little scientific evidence that they work. You may find teas that contain licorice, chamomile, slippery elm, marshmallow, fennel, or ginger help you (Dossett, 2017).

When to see your healthcare provider

Be sure to see your primary care healthcare professional or gastroenterologist as soon as possible if:

Your heartburn episodes increase.

Your heartburn episodes get more painful or intense.

You develop a constant cough.

You can’t swallow.

You lose weight without trying.

You lose your voice.

These may be symptoms of something more serious.

If you experience chest, arm, or jaw pain with your heartburn, please go to the nearest emergency room.

Some people may be more sensitive to acid reflux trigger foods than others. You may also have food intolerances to other foods that show up as heartburn, bloating, or nausea. You may want to track your food intake and see what causes your acid reflux symptoms to flare up. It’s best to track for at least a full week or even longer to get a clearer picture of what affects you (Dossett, 2017).

An acid reflux diet can control or decrease your symptoms. Eating healthfully by reducing high-fat, simple carb, alcohol, and acidic food and drink may reduce your GERD symptoms and improve your overall health and quality of life.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Antunes, C., Aleem, A., & Curtis, S. A. (2020). Gastroesophageal reflux disease. StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from: https://www.statpearls.com/ArticleLibrary/viewarticle/22098

Dossett, M. L., Cohen, E. M., & Cohen, J. (2017). Integrative medicine for gastrointestinal disease. Primary care, 44(2), 265–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.02.002. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5605819/

Ha, J. O., Lee, T. H., Lee, C. W., Park, J. Y., Choi, S. H., Park, H. S., et al. (2016). Prevalence and risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab J, 40(4), 297-307. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2016.40.4.297. Retrieved from: https://synapse.koreamed.org/upload/SynapseData/PDFData/2004DMJ/dmj-40-297.pdf

MacFarlane B. (2018). Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in adults: a pharmacist's perspective. Integrated pharmacy research & practice, 7, 41–52. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S142932. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5993040/

Newberry, C., & Lynch, K. (2019). The role of diet in the development and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: why we feel the burn. Journal of thoracic disease, 11(Suppl 12), S1594–S1601. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.06.42. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6702398/

Pan, J., Cen, L., Chen, W., Yu, C., Li, Y., & Shen, Z. (2019). Alcohol consumption and the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 54(1), 62-69. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agy063. Retrieved from: https://academic.oup.com/alcalc/article/54/1/62/5090261

Salehi, B., Sharifi-Rad, R., Sharopov, F., Namiesnik, J., Roointan, A., Kamle, M., et al. (2019). Beneficial effects and potential risks of tomato consumption for human health: an overview. Nutrition, 62, 201-208. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2019.01.012. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0899900718312577

Sethi S, Richter JE. (2017). Diet and gastroesophageal reflux disease: role in pathogenesis and management. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology; 33(2):107-111. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000337. PMID: 28146448. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28146448/

Shibata, T., Nakamura, M., Omori, T., Tahara, T., Ichikawa, Y., Okubo, M., et al. (2015). Association between individual response to food taste and gastroesophageal symptoms. Journal of digestive diseases, 16(6), 337-341. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12246. Retrieved from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1751-2980.12246

Surdea-Blaga T, Negrutiu DE, Palage M, Dumitrascu DL. (2019). Food and gastroesophageal reflux Disease. Current Medicinal Chemistry;26(19):3497-3511. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170515123807. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28521699/

Weijenborg, P. W., de Schepper, H. S., Smout, A. J., & Bredenoord, A. J. (2015). Effects of antidepressants in patients with functional esophageal disorders or gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 13(2), 251-259. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.025. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S154235651400932X

Zhang, M., Hou, Z. K., Huang, Z. B., Chen, X. L., & Liu, F. B. (2021). Dietary and lifestyle factors related to gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Therapeutics and clinical risk management, 17, 305–323. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S296680. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8055252/