Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

It’s normal to feel overwhelmed when trying to find a therapist. But it’s an important first step to take if you need help managing your mental health, working through a trauma, or improving a relationship.

Fortunately, there are a few tips that you can follow to find the right therapist for you.

Tips for finding a therapist

Finding a good therapist can feel like looking for a needle in a haystack. And because therapy isn’t one-size-fits-all, techniques that work for one person may not work for another. That’s why it’s important to find a therapist you can trust and who can help you make the changes you’re hoping to achieve.

The following are 10 tips to help you find the right therapist, including finding a mental health provider with the right background, looking into online therapy, asking friends for recommendations, and more.

1. Match your goals with expertise

Writing down a list of your treatment goals before you start can help tailor your search.

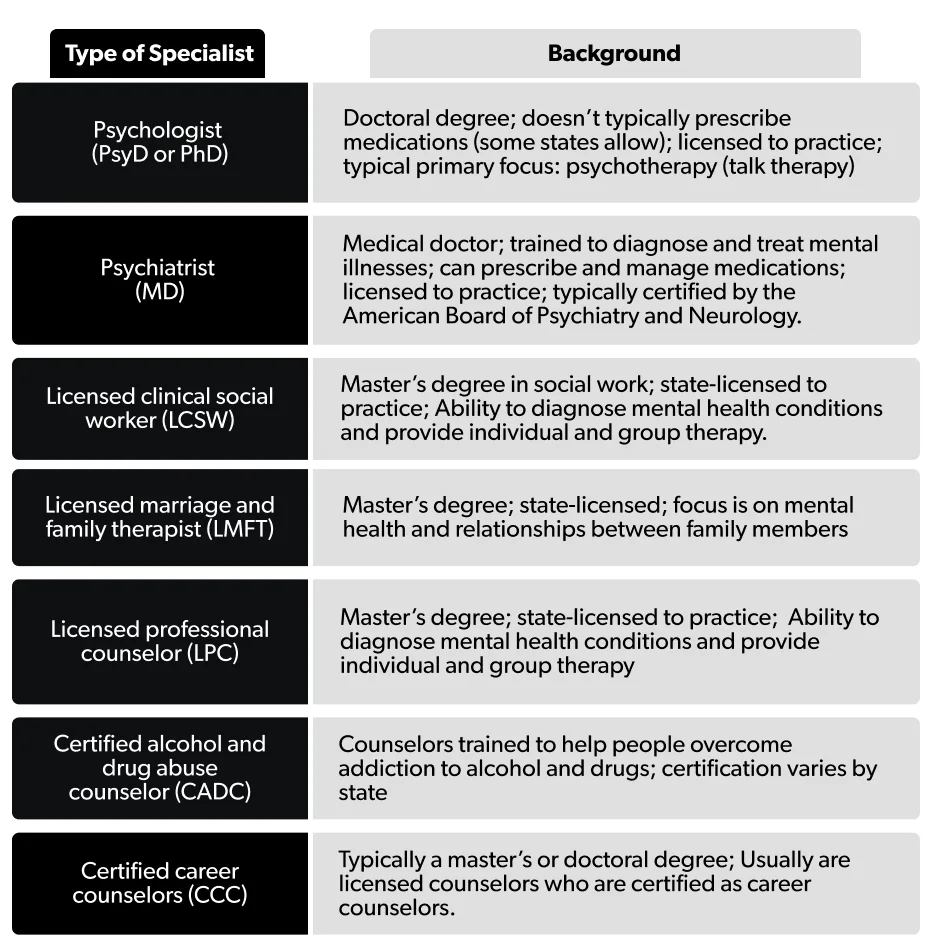

Mental health counselors come with different backgrounds, training, and specializations. For example, psychiatrists are licensed to prescribe medications and may be helpful if you are experiencing a serious mental illness or another provider believes medication may be an important part of your treatment (Cook, 2017). But if you are having marital or relationship problems, seeking out couples or family therapists may be a better approach.

Here is a quick look at the different types of therapists and what they specialize in treating:

Many licensed therapists can talk about a wide range of issues and may offer cognitive-behavioral therapy or other types of psychotherapy, also known as talk therapy. And many will offer a free consultation so you can see whether they’re the right fit for you (more on that later).

If you are not seeking individual therapy, there is also the option of group therapy, which can be good for various conditions, such as battling some forms of substance abuse or social anxiety.

Group therapy is led by a therapist and should not be confused with support groups. Support groups are also beneficial but are not considered formal therapy (APA, 2019).

2. Check insurance coverage and costs

It’s not unusual that someone starts therapy only to find they can’t afford to continue. If you plan to have your health insurance company cover most of the costs of therapy, check your insurance plan and its provider network.

Asking the following questions can help get an idea of the long-term costs of therapy (APA, 2017):

Does my plan cover out-of-network therapists?

What are the copays?

How many sessions are covered per year?

If you don’t have insurance, it’s even more important to ask for all costs involved. Some therapists will offer a sliding scale based on income or other circumstances.

3. Ask your primary care provider

Your physician typically has a medically reviewed network they can tap for referrals for a licensed therapist.

One study shows that when primary care physicians are actively involved in advising people to seek mental health counseling, outcomes are better. This is because people feel more motivated to seek therapy if their doctors suggest it (Allen, 2017).

It’s also good to get medical advice about any health diagnosis or treatment that could affect your mental health. For instance, having insomnia is linked to depression (Hertenstein, 2019). Treating physical health problems can often improve mental health and mood.

4. Ask friends and colleagues

Often, a friend or trusted colleague may know of a therapist they like and respect. But keep in mind that your therapy goals may differ from those in your friend circles.

However, word of mouth can be a good way to get feedback. Unlike other businesses, therapists can’t ask for online reviews due to ethical standards.

5. Contact community organizations

A variety of community organizations may have referrals for therapists or other support services in your area. It may help to check resource lists from:

Community mental health centers

Colleges: While they cater to students, they may offer publicly available resource lists.

Churches, synagogues, and mosques

Workplaces: Check your workplace’s wellness plan to see if it offers mental health support.

6. Seek out advocacy groups

If you are dealing with addiction, anxiety, trauma, or a range of other mental health issues, there’s likely an organization that provides advocacy and outreach.

Some offer online support services, including provider lists. The following are some of the national organizations advocating mental health issues (NIMH, 2021):

There are also a growing number of resources and provider lists of therapists who are familiar with issues faced by the LGBQT+ community and people of color, including:

7. Try mental health professional locators

In addition to some advocacy groups that list providers, there are a variety of professional organizations that have online therapist locators.

Some of these include:

8. Consider online therapy

Online therapy can increase your chances of finding a therapist that works for you.

Studies have shown that online therapy sessions can boost well-being by offering effective alternatives to traditional therapy. And one study found people with depression felt that their symptoms improved after online sessions (Marcelle, 2019).

There are cases where in-person therapy is preferable, so it’s best to consult with a potential therapist about your specific goals and background.

9. Schedule a meeting

Before your first session, it helps to schedule an online, phone, or in-person discussion (some therapists will refer to this as a consultation) to get a feel for whether or not the therapist is going to be a good fit.

During this time, you can discuss your treatment goals and see if you feel comfortable talking with them. Overall, you want to feel the therapist is listening to you and responding in a way that shows they are respectful of your concerns and your time and are invested in offering solutions based on your goals.

During your consultation, you can ask them questions like (APA, 2017):

Do you have experience helping people with the issue I want help with?

What kinds of treatments do you use, and have they been proven effective for dealing with my problem or issue?

What are typical treatment challenges for my issue?

What results should I expect?

How long will it take to see benefits or meet my goals?

10. Don’t settle: find the right fit

A therapist’s long list of credentials won’t necessarily guarantee you will feel comfortable with them. Studies show that treatment is more successful if those being counseled are fully engaged and have a good bond with their therapist (Allen, 2017).

It’s common to see a few therapists before finding the right fit. In short, don’t feel bad about switching if it’s not a good match.

Benefits of therapy

Psychotherapy can be used alone or in combination with medication, depending on each person’s needs. The benefits typically include finding ways to better manage self-defeating thinking, fear, or how to interact in situations or with other people, including loved ones (NIMH, 2021).

While there are different approaches to therapy, all should include empathy, warmth, cooperation, and transparency. If you feel you are not getting this or are not advancing towards your goals, don’t be afraid to try a different approach or a different therapist (Locher, 2019; Cook, 2017).

Therapy sessions typically change and develop over time. Talk to your therapist about your goals and how they will help you build new skills to manage your challenges. It’s important to think of it as a partnership. There will be work to do, but it’s worth the effort.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Allen, M. L., Cook, B. L., Carson, N., et al. (2015). Patient-provider Therapeutic Alliance contributes to patient activation in community mental health clinics. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 44 (4), 431–440. doi:10.1007/s10488-015-0655-8. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30537570/#:~:text=The%20results%20suggest%20that%20insomnia,%2C%20CI%201.03%2D1.59

American Psychological Association (APA). (2017). How to choose a psychologist . Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/psychotherapy/choose-therapist

American Psychological Association (APA). (2019). Psychotherapy: Understanding group therapy . Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/psychotherapy/group-therapy

Cook, S. C., Schwartz, A. C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2017). Evidence-based psychotherapy: Advantages and challenges. Neurotherapeutics , 14 (3), 537–545. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0549-4. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5509639/

Hertenstein, E., Feige, B., Gmeiner, T., et al. (2019). Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews , 43 , 96–105. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30537570/#:~:text=The%20results%20suggest%20that%20insomnia,%2C%20CI%201.03%2D1.59

Locher, C., Meier, S., & Gaab, J. (2019). Psychotherapy: A world of meanings. Frontiers in Psychology , 10 . doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00460. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6448000/

Marcelle, E. T., Nolting, L., Hinshaw, S. P., et al. (2019). Effectiveness of a multimodal digital psychotherapy platform for Adult Depression: A naturalistic feasibility study. JMIR MHealth and UHealth , 7 (1). doi:10.2196/10948. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6364202/

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2021). Psychotherapies . Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/psychotherapies