Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Pantoprazole and alcohol

Pantoprazole and other proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) reduce the amount of stomach acid your body makes and are commonly used to treat acid reflux, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and peptic ulcer disease (PUD).

Although alcohol does not directly interact with pantoprazole (brand name Protonix), it can cause your stomach to generate more acid than normal—the exact condition the medication is meant to correct (NHS, 2018).

At certain concentrations, alcohol has been shown to increase the production of gastric acid in the stomach. Some research suggests that beverages with lower alcohol content (5% alcohol by volume) like beer and wine are more likely to increase stomach acid production than beverages with a higher concentration, such as whisky and gin (Chari, 1993).

Additionally, drinking too much or too often can irritate your stomach lining and exacerbate underlying symptoms and conditions, such as heartburn and stomach ulcers (NHS, 2018).

What are proton pump inhibitors?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are a type of medication used to block or reduce the production of stomach acid (NHS, 2018).

Pantoprazole and other PPIs—such as omeprazole (brand name Prilosec), lansoprazole (brand name Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), and others—turn off the production of gastric acid in your stomach, which can help reduce the amount of acid and prevent or alleviate painful symptoms of certain conditions (Wolfe, 2020).

What is pantoprazole used for?

Pantoprazole is a PPI that is frequently used to treat the following conditions (NHS, 2018):

Acid reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD)

What is acid reflux?

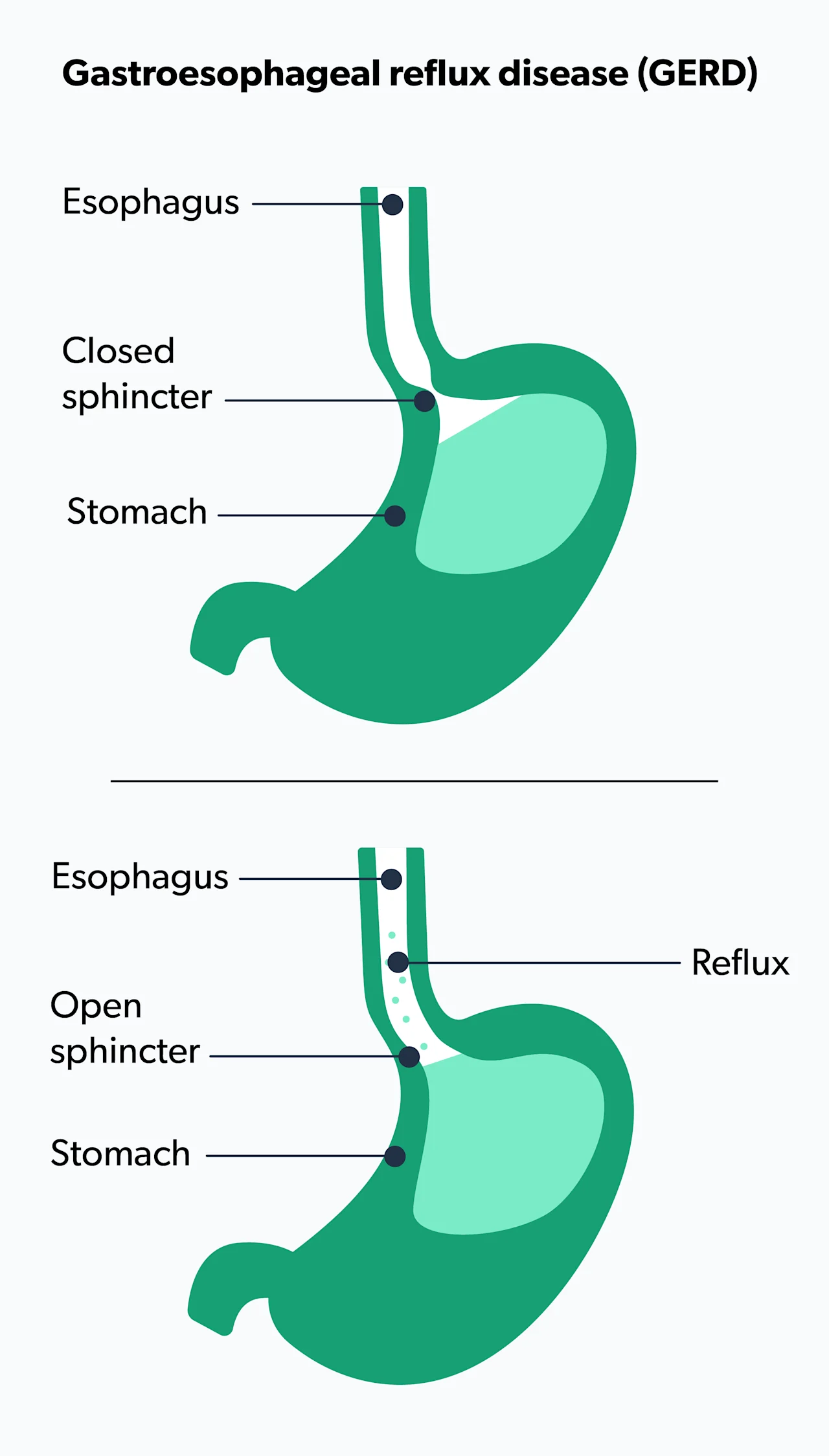

Acid reflux is a common medical condition that occurs when your stomach contents flow back into your esophagus (the tube that runs from the mouth to the stomach). This can cause a painful sensation in the middle of the chest called heartburn, especially after big meals (ACG, n.d.).

Not sure what heartburn feels like? Most people describe it as a burning chest pain behind the breast bone that travels up through the neck and throat. It may even feel like your food is moving back up through the esophagus, leaving a bitter taste in your mouth.

Medication for acid reflux

To cope with acid reflux, your healthcare provider will likely suggest lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter medications to help you find relief.

For example, small and frequent meals, loose-fitting clothes, and not lying down for three hours after a meal may help reduce symptoms. Antacids that neutralize stomach acid—such as Alka-Seltzer, Maalox, Mylanta, Rolaids, and Riopan—are often the first non-prescription drugs recommended to relieve heartburn and mild acid reflux symptoms (NIDDK, 2007).

What is GERD?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic and more severe form of acid reflux. You might be diagnosed with GERD if your acid reflux occurs more than twice per week.

Some of the most common symptoms of GERD can include (Vakil, 2006):

Heartburn

Regurgitation (when the food rises back up into your throat)

A sour taste in your mouth, especially after lying down or when you wake up in the morning

Less commonly, GERD can cause bloody coughs, bloody stool, iron-deficiency anemia, weight loss, or difficulty swallowing. If you experience any of these symptoms, it’s important that you meet with a healthcare professional to evaluate your condition (Vakil, 2006).

Medication for GERD

As explained earlier, heartburn is pretty common, and occasional heartburn after a meal isn’t usually something to be concerned about.

Obesity, pregnancy, and smoking can contribute to GERD, so the condition can sometimes be managed by avoiding foods and beverages that worsen symptoms and cutting back on smoking (NIDDK, 2007).

When heartburn is a symptom of a more severe problem, your healthcare provider may suggest treatment involving a PPI like pantoprazole. If your heartburn becomes frequent or uncomfortable, speak with your healthcare provider to discuss whether you might need a more thorough evaluation. Your doctor may recommend tests such as an upper endoscopy (where they examine your throat with a camera) or a barium swallow test (where you are asked to drink a special liquid while they take x-rays) to see if there are any structural problems contributing to your reflux.

What is peptic ulcer disease?

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is when painful sores develop in the lining of the stomach or small intestine (AGA, n.d.). Stomach ulcers develop on the inside of the stomach, while duodenal ulcers are found on the inside of the upper portion of your small intestine.

Peptic ulcer disease typically occurs for one of two reasons (AGA, n.d.):

Most commonly, it’s caused by an infection in the stomach lining caused by a bacteria called Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

Another common cause is overuse of NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)—such as ibuprofen (brand names Advil and Motrin) and aspirin. NSAIDs are used to alleviate aches, pains, and swelling, and taking too much of them or taking them for too long can result in the development of ulcers in the lining of the stomach.

While spicy food may make your symptoms worse, it does not cause ulcers. Stress, however, can contribute to the development of gastric ulcers (Lee, 2017).

Serious stomach pain is the most common symptom of an ulcer. The burning sensation can be unpredictable, happening at any time of the day or night, and lasting from a few minutes to several hours. Less common adverse effects include an upset stomach, vomiting, and loss of appetite (AGA, n.d.).

Treatment

If you’re experiencing any of the symptoms mentioned above, meet with your healthcare provider to discuss treatment for PUD.

To understand if H. pylori infection is the cause of your PUD, your healthcare provider might conduct a simple breath test called the urea breath test or ask for a stool sample to check for the infection. If you’ve been taking medication such as PPIs, you will have to stop taking them before the test (Crowe, 2020).

Treatment for H. pylori typically lasts 10–14 days and involves the use of two types of antibiotics and a PPI like pantoprazole. This combination will help alleviate the discomfort and clear the infection (Chiba, 2013). While your symptoms may improve before you finish the full course of treatment, it’s very important to follow your healthcare provider’s instructions to ensure that the infection is treated completely and to reduce the likelihood that it will return (Crowe, 2020).

If NSAIDs are the source of your peptic ulcers, your healthcare provider will advise you to stop the medication and find an alternative option if possible. This treatment will also likely include the use of PPIs to alleviate the symptoms and allow the ulcers to heal (Vakil, 2020).

Protonix over-the-counter (OTC)

Protonix (pantoprazole sodium) is approved by the FDA for the short-term treatment of the following conditions (FDA, 2012):

Erosive esophagitis (esophagus inflammation) associated with GERD

Treatment for erosive esophagitis

Conditions like Zollinger Ellison syndrome (a rare disorder associated with the production of excess stomach acid)

Protonix is available as a tablet that should be swallowed whole and never split, crushed, or chewed. For most people, it’s best taken 30 to 60 minutes before a meal, usually breakfast. Protonix is also available as an injection administered in a hospital setting. For people who have difficulty swallowing pills, there are other options such as granules that are taken with applesauce (FDA, 2012).

Protonix generic

Pantoprazole is the generic version of Protonix. It’s identical to the brand name drug in usage and dosage as well as safety and effectiveness.

Like all medications, it’s best to take as directed on the drug label. Generally speaking, the advice is to take the lowest dose for the shortest amount of time needed to treat your condition. This will allow you to achieve relief while allowing your healthcare provider to rule out any other potential causes for your symptoms. Never take a double dose to make up for a missed dose (DailyMed, n.d).

Pantoprazole side effects

Clinical trials have found that the most frequently reported side effect of pantoprazole is headache. Other common side effects include digestive complaints like diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, and gas. Some people also reported dizziness or muscle pain, but it was much less frequent (DailyMed, n.d).

Long-term use of PPIs like pantoprazole can affect the delicate balance of bacteria in the digestive system and lead to Clostridium difficile (C. diff), a bacterial infection that causes persistent diarrhea (FDA, 2017). If you take PPIs and develop persistent diarrhea, consult with your healthcare provider to rule out this condition.

Taking proton pump inhibitors like pantoprazole makes your stomach less acidic but can also make it difficult for your body to absorb certain nutrients, such as magnesium. Magnesium deficiency can cause muscle spasms and weakness, but usually only happens when people take PPIs for more than three months. Less frequently, people taking PPIs for more than two years can develop a vitamin B12 deficiency (Lam, 2013). If you are taking PPIs for a long period of time, your healthcare provider may want to do a simple blood test to make sure you don’t develop one of these conditions.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). (n.d.). Acid reflux. Retrieved on Sep.10, 2020 from https://gi.org/topics/acid-reflux/

American Gastroenterological Association (AGA). (n.d). Peptic ulcer disease. Retrieved on Sep. 10, 2020 from https://gastro.org/practice-guidance/gi-patient-center/topic/peptic-ulcer-disease/

Chari, S., Teyssen, S., & Singer, M. V. (1993). Alcohol and gastric acid secretion in humans. Gut, 34 (6), 843–847. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.34.6.843. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1374273/

Chiba, T., Malfertheiner, P., & Satoh, H. (2013). Proton pump inhibitors: A balanced view. Gastrointestinal Research, 32 , 59-67. doi:10.1159/000350631. Retrieved from https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/350631

Crowe, S. E. (2020, January 09). UpToDate. Treatment regimens for Helicobacter pylori. Retrieved on Oct. 20, 2020 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-regimens-for-helicobacter-pylori?search=h.pylori

DailyMed. (n.d). PANTOPRAZOLE SODIUM- pantoprazole tablet, delayed release. Retrieved on Oct. 20, 2020 from https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=f3ded82a-cf0d-4844-944a-75f9f9215ff0

Food and Drug administration (FDA). (2012). Protonix. Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/020987s045lbl.pdf

Heinze, H. & Fischer, R. (2012). Lack of interaction between pantoprazole and ethanol. a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in healthy volunteers. Clinical Drug Investigation, 21, 345-351. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200121050-00004. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.2165%2F00044011-200121050-00004

Lam, J.R., Schneider, J.L., Zhao, W., & Corley, D.A. (2013). Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310 (22): 2435-2442. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280490. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1788456

Lee, Y. B., Yu, J., Choi, H. H., Jeon, B. S., Kim, H. K., Kim, S. W., et al. (2017). The association between peptic ulcer diseases and mental health problems: A population-based study: a STROBE compliant article. Medicine (Baltimore), 96 (34): e7828. doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007828. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5572011/

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). (2014). Harmful interactions. Retrieved Oct. 20, 2020 from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/harmful-interactions-mixing-alcohol-with-medicines#:~:text=The%20danger%20is%20real.,problems%2C%20and%20difficulties%20in%20breathing

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). (2007). Heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux (GER), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Retrieved Oct. 20, 2020 from http://sngastro.com/pdf/heartburn.pdf

United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS). (2018). Pantoprazole. Retrieved on Oct. 20, 2020 from https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/pantoprazole/

Vakil, N. B. (2020, April 1). UpToDate. Peptic ulcer disease: Treatment and secondary prevention. Retrieved Oct. 20, 2020 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/peptic-ulcer-disease-treatment-and-secondary-prevention

Vakil, N., Zanten, S. V., Kahrilas, P., Dent, J., & Jones, R. (2006). The Montreal Definition and Classification of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Global Evidence-Based Consensus. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 101 (8): 1900-1920. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16928254/

Wolfe, M. M. (2020, July 13). UpToDate. Proton pump inhibitors: Overview of use and adverse effects in the treatment of acid related disorders. Retrieved Oct. 20, 2020 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/proton-pump-inhibitors-overview-of-use-and-adverse-effects-in-the-treatment-of-acid-related-disorders