Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If you have a uterus, you’re probably used to monthly bleeding and cramps. But if your symptoms have gone from bad to worse, or if you’ve noticed heavier bleeding, bleeding between periods, or worsening abdominal pain, fibroids may be the culprit.

Fibroids are common. These non-cancerous masses can grow in or around the uterus. In fact, fibroids can affect up to 80% of women by the age of 50 (DeLaCruz, 2017).

Here’s what you need to know about fibroids––and what you can do about them.

What are fibroids?

Fibroids, also known as leiomyomas, can develop when the muscle that makes up the uterus grows in areas or in ways that it’s not supposed to. While discovering that you have a mass in or on your uterus can be scary, know that fibroids are typically benign, meaning they’re not cancerous.

There are different types of fibroids, which are typically classified by their location and shape. When they protrude into the center of the uterus, they’re called submucosal fibroids. When they’re in between layers of the uterine wall, they’re called intramural fibroids. When they grow on the outside of the uterus, they’re called subserosal fibroids.

They can appear one at a time, or multiple fibroids can grow at once. They may grow slowly or quickly, and some cause symptoms while others do not.

Symptoms of fibroids

While most fibroids don’t cause any noticeable issues, about 25% of people with them report effects severe enough to affect their daily lives. These include (Borah, 2013; Giuliani, 2020):

Bleeding: Fibroids can cause heavy periods or bleeding in between cycles. The blood loss from this may be significant enough to cause anemia.

Pain: You may experience backaches, painful period cramps, pelvic pain, or discomfort during sex. The pain from fibroids ranges from mild to severe.

Constipation: Large fibroids may put pressure on the colon, making it more difficult to pass a bowel movement.

Urinary problems: The same goes for your bladder. If fibroids are pressing on the bladder it can cause more frequent urination or a constant urge to pee. If the fibroids are pressing on the urethra (the tube that carries urine from your bladder out of your body), it can also cause urinary retention (meaning it’s more difficult to urinate).

Infertility: Sometimes, fibroids in the uterus can make it more difficult to get pregnant.

What causes uterine fibroids to grow?

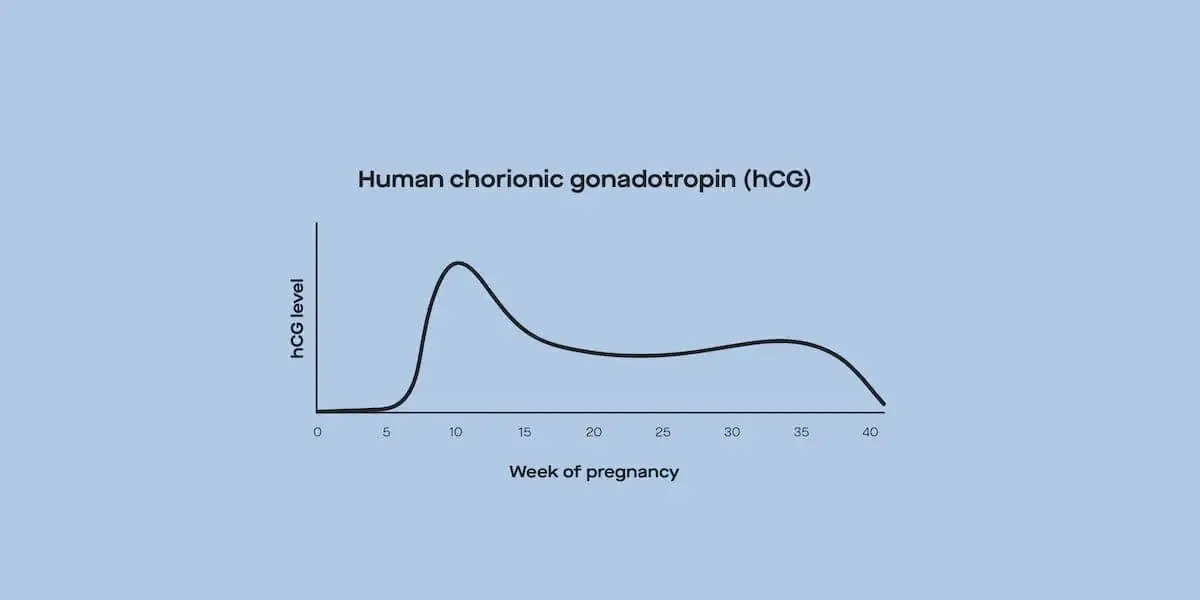

Fibroids grow for different reasons. Many risk factors are related to your hormone levels. For example, things that cause estrogen levels to soar and progesterone to drop may make it more likely to get fibroids. Factors that can contribute to an increased risk of fibroids include (Wise, 2004; Chiaffarino, 1999):

Getting your first period very young (before age 10)

Never having been pregnant

A history of obesity

A family history of fibroids

People who’ve had multiple pregnancies, take oral contraceptive pills, or get their first period after age 16 are less likely to develop fibroids.

How do you know if you have fibroids?

If you have symptoms like heavy bleeding or abdominal pain, your healthcare provider will likely perform a physical examination during which they’ll place a gloved hand in your vagina and another on your abdomen to evaluate the position and size of your uterus.

They may also perform a transvaginal ultrasound, which is a test during which a wand is placed inside the vagina and used to display an image of the uterus and ovaries on a screen. This test is very accurate and can find up to 99% of fibroids (De La Cruz, 2017).

Further testing using a hysteroscopy might be used, too. This involves inserting a small camera through the vagina and the cervix to examine the inside of the uterus. Another option is a hysterosalpingogram, which uses a special dye and an X-ray to examine the inside of the uterus.

Can you shrink fibroids?

Fibroids aren’t always there to stay. Many smaller fibroids shrink and disappear on their own within six months to three years. Others shrink following pregnancy or after menopause. If you’re not experiencing severe symptoms, your healthcare provider may recommend watching and waiting to see if they resolve naturally (DeWaay, 2002, De La Cruz, 2017).

If your fibroids don’t go away on their own, are causing a lot of pain, or if you’re experiencing fertility issues, there are medications that may be able to help.

How do you treat fibroids?

There are several treatment options for fibroids, including medication and surgery. The most common treatments include:

Medication

Since hormones like estrogen can make fibroids grow, treatments that adjust your hormone levels may help shrink them. Various contraceptives like birth control pills, vaginal hormone rings, and hormonal IUDs (intrauterine devices) can adjust hormone levels to reduce excessive bleeding and shrink fibroids (De La Cruz, 2017).

Another option is tranexamic acid. This drug helps blood clot and reduces vaginal bleeding (Bryant-Smith, 2018).

Surgery

Surgery may be a good option if fibroids are large, causing symptoms, or don’t resolve after treatment with medication. One type of surgery called a myomectomy can be done to remove the fibroids. Whether this surgery is an option depends on the location of the fibroids and their size.

A myomectomy may be done as a laparoscopic procedure (surgery through a tiny incision) so your recovery is faster and there are fewer complications (Tanos, 2018). One disadvantage of this procedure is that 1/3 of fibroids end up growing back (De La Cruz, 2017).

In some cases––like if fibroids are buried deep in the wall of the uterus, they’re difficult to access for surgical removal, or you’re not interested in preserving your fertility––a healthcare provider may recommend a hysterectomy. This is an operation that removes the uterus entirely. Most hysterectomies are actually performed due to fibroids (Baird, 2003).

An advantage to a hysterectomy is that fibroids can’t grow back since the uterus isn’t there anymore. However, one issue to consider is that after a hysterectomy you can no longer carry a pregnancy.

Other treatments

A special technique called uterine artery embolization can be performed to block the blood supply to the fibroids. Without adequate blood flow, the fibroids shrink. This procedure is less invasive than surgery and usually allows for faster recovery and a shorter hospital stay.

One study found that uterine artery embolization entirely or almost completely resolved over 96% of fibroids (Yoon, 2018). However, some reviews suggest this procedure has a higher risk of minor complications and need for future surgeries (Gupta, 2014).

Another possible treatment is a medication called a GnRH agonist (gonadotropin receptor hormone agonist). These drugs regulate hormone levels. Clinical trials demonstrate that GnRH agonists significantly improve heavy menstrual bleeding compared to placebo, though some people who use them experience side effects like hot flashes (Schlaff, 2020).

If you have uterine fibroids, you’re not alone. Fibroids are a common condition and there are solutions if these growths are painful or causing other symptoms. It’s a good idea to talk to a healthcare professional about the best treatment options for you.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. (2021). Management of Symptomatic Uterine Leiomyomas: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 228. Obstetrics and Gynecology , 137 (6), e100–e115. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004401. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34011888/

Baird, D. D., Dunson, D. B., Hill, M. C., Cousins, D., & Schectman, J. M. (2003). High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology , 188 (1), 100–107. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.99. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12548202/

Borah, B. J., Nicholson, W. K., Bradley, L., & Stewart, E. A. (2013). The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology , 209 (4). doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.017. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4167669/

Bryant-Smith, A. C., Lethaby, A., Farquhar, C., & Hickey, M. (2018). Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4 (4). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000249.pub2. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6494516/

Chiaffarino, F., Parazzini, F., La Vecchia, C., Chatenoud, L., Di Cintio, E., & Marsico, S. (1999). Diet and uterine myomas. Obstetrics and Gynecology , 94 (3), 395–398. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00305-1. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10472866/

De La Cruz, M. S., & Buchanan, E. M. (2017). Uterine Fibroids: Diagnosis and Treatment. American Family Physician , 95 (2), 100–107. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28084714/

DeWaay, D. J., Syrop, C. H., Nygaard, I. E., Davis, W. A., & Van Voorhis, B. J. (2002). Natural history of uterine polyps and leiomyomata. Obstetrics and Gynecology , 100 (1), 3–7. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02007-0. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12100797/

Eggert, S. L., Huyck, K. L., Somasundaram, P., Kavalla, R., Stewart, E. A., Lu, A. T., et al. (2012). Genome-wide linkage and association analyses implicate FASN in predisposition to Uterine Leiomyomata. American Journal of Human Genetics , 91 (4), 621–628. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.009. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23040493/

Giuliani, E., As-Sanie, S., & Marsh, E. E. (2020). Epidemiology and management of uterine fibroids. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics , 149 (1), 3–9. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13102. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31960950/

Gupta, J. K., Sinha, A., Lumsden, M. A., & Hickey, M. (2014). Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, CD005073. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub4. Retrieved from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub4/full

James-Todd, T. M., Chiu, Y. H., & Zota, A. R. (2016). Racial/ethnic disparities in environmental endocrine-disrupting chemicals and women's reproductive health outcomes: epidemiological examples across the life course. Current Epidemiology Reports , 3 (2), 161–180. doi:10.1007/s40471-016-0073-9. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28497013/

Laughlin, S. K., Herring, A. H., Savitz, D. A., Olshan, A. F., Fielding, J. R., Hartmann, K. E., & Baird, D. D. (2010). Pregnancy-related fibroid reduction. Fertility and Sterility , 94 (6), 2421–2423. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.035. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20451187/

Lethaby, A. & Vollenhoven, B. (2015). Fibroids (uterine myomatosis, leiomyomas). BMJ Clinical Evidence . Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26032466/

Marret, H., Fritel, X., Ouldamer, L., Bendifallah, S., Brun, J. L., De Jesus, I., et al. (2012). Therapeutic management of uterine fibroid tumors: updated French guidelines. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology , 165 (2), 156–164. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.07.030. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22939241/

Munro, M. G., Critchley, H. O., Fraser, I. S., & FIGO Menstrual Disorders Working Group (2011). The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years. Fertility and Sterility , 95 (7), 2204–2208. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.03.079. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28084714/

Nicholson, W. K., Wegienka, G., Zhang, S., Wallace, K., Stewart, E., Laughlin-Tommaso, S., et al. (2019). Short-Term Health-Related Quality of Life After Hysterectomy Compared With Myomectomy for Symptomatic Leiomyomas. Obstetrics and Gynecology , 134 (2), 261–269. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003354. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31306318/

Ross, R. K., Pike, M. C., Vessey, M. P., Bull, D., Yeates, D., & Casagrande, J. T. (1986). Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) , 293 (6543), 359–362. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6543.359. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3730804/

Schlaff, W. D., Ackerman, R. T., Al-Hendy, A., Archer, D. F., Barnhart, K. T., Bradley, L. D., et al. (2020). Elagolix for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding in Women with Uterine Fibroids. The New England Journal of Medicine , 382 (4), 328–340. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1904351. Retrieved from https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa1904351?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

Stewart, E. A. (2015). Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. The New England Journal of Medicine , 372 (17), 1646–1655. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1411029. Retrieved from https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMcp1411029?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed

Tanos, V., Berry, K. E., Frist, M., Campo, R., & DeWilde, R. L. (2018). Prevention and Management of Complications in Laparoscopic Myomectomy. BioMed Research International . doi:10.1155/2018/8250952. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5859837/

Wise, L. A., Palmer, J. R., Harlow, B. L., Spiegelman, D., Stewart, E. A., Adams-Campbell, L. L., & Rosenberg, L. (2004). Reproductive factors, hormonal contraception, and risk of uterine leiomyomata in African-American women: a prospective study. American Journal of Epidemiology , 159 (2), 113–123. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh016. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1847588/

Yoon, J. K., Han, K., Kim, M. D., Kim, G. M., Kwon, J. H., Won, J. Y., et al. (2018). Five-year clinical outcomes of uterine artery embolization for symptomatic leiomyomas: An analysis of risk factors for reintervention. European Journal of Radiology, 109, 83–87. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.10.017. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30527317/