Key takeaways

A “hormonal belly” describes increased belly fat that may be caused by an imbalance of certain hormones.

Several factors may cause this type of abdominal weight gain, including chronic stress, insulin resistance, sex hormone imbalances, and chronic health conditions.

Techniques to reduce a hormonal belly may include treating underlying conditions, modifying diet and exercise, and managing stress.

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Key takeaways

A “hormonal belly” describes increased belly fat that may be caused by an imbalance of certain hormones.

Several factors may cause this type of abdominal weight gain, including chronic stress, insulin resistance, sex hormone imbalances, and chronic health conditions.

Techniques to reduce a hormonal belly may include treating underlying conditions, modifying diet and exercise, and managing stress.

If you’re experiencing weight gain around your midsection regardless of how much you work out or what you eat, you could have a”‘hormonal belly.” While it’s not a medical term or condition, a hormonal belly describes excess abdominal fat that may be a sign of a hormonal imbalance or underlying health condition.

We all need some adipose tissue (fat) for optimal health and to support the body’s hormonal processes, cellular functions, and vitamin absorption, and to protect our internal organs and regulate body temperature.

However, some hormonal imbalances or health conditions can contribute to the storage of visceral fat—the kind of fat that surrounds internal organs and can push the belly out. Too much visceral fat can increase the risk of certain health issues such as heart disease, diabetes, and stroke.

Read on to learn about the signs and symptoms of a hormonal belly, what causes it, how to lose hormonal belly fat, and more.

What is a hormonal belly?

A hormonal belly (also sometimes called a “hormone belly”) describes excess fat accumulation around the abdomen. “Hormonal belly” isn’t a medical condition itself but could be a sign of an underlying issue.

This type of weight gain may occur regardless of your diet or how much you exercise and may be due to potential hormonal imbalances, medications, or chronic health conditions.

What does a hormonal belly look like?

The most obvious symptom of a hormonal belly is unexplained weight gain around your midsection.

Hormonal imbalances or dysregulation may cause other symptoms in addition to abdominal weight gain and may vary depending on the underlying cause.

Other symptoms of hormonal imbalance

Some possible signs of hormonal imbalance may include:

Abdominal or pelvic pain

Fatigue

Appetite changes, especially increased hunger

Bloating or distention

Sleep changes or poor sleep

Cravings, especially for sugar or refined carbohydrates

Feeling cold

Gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, constipation)

Unwanted hair growth

Hot flashes

Erectile dysfunction (ED)

Low libido or libido changes

Skin changes such as dry skin or acne

Hormonal imbalances may also cause emotional, psychological, or cognitive symptoms, such as:

Brain fog

Depression

Mood changes

Stress

What causes a hormonal belly?

Various factors—including lifestyle, sex, age, and genetics—can cause belly fat.

However, several more complex factors—from chronic stress and natural aging processes to medical conditions and certain medications—may cause other health issues that can impact hormones and lead to excess weight gain around your midsection.

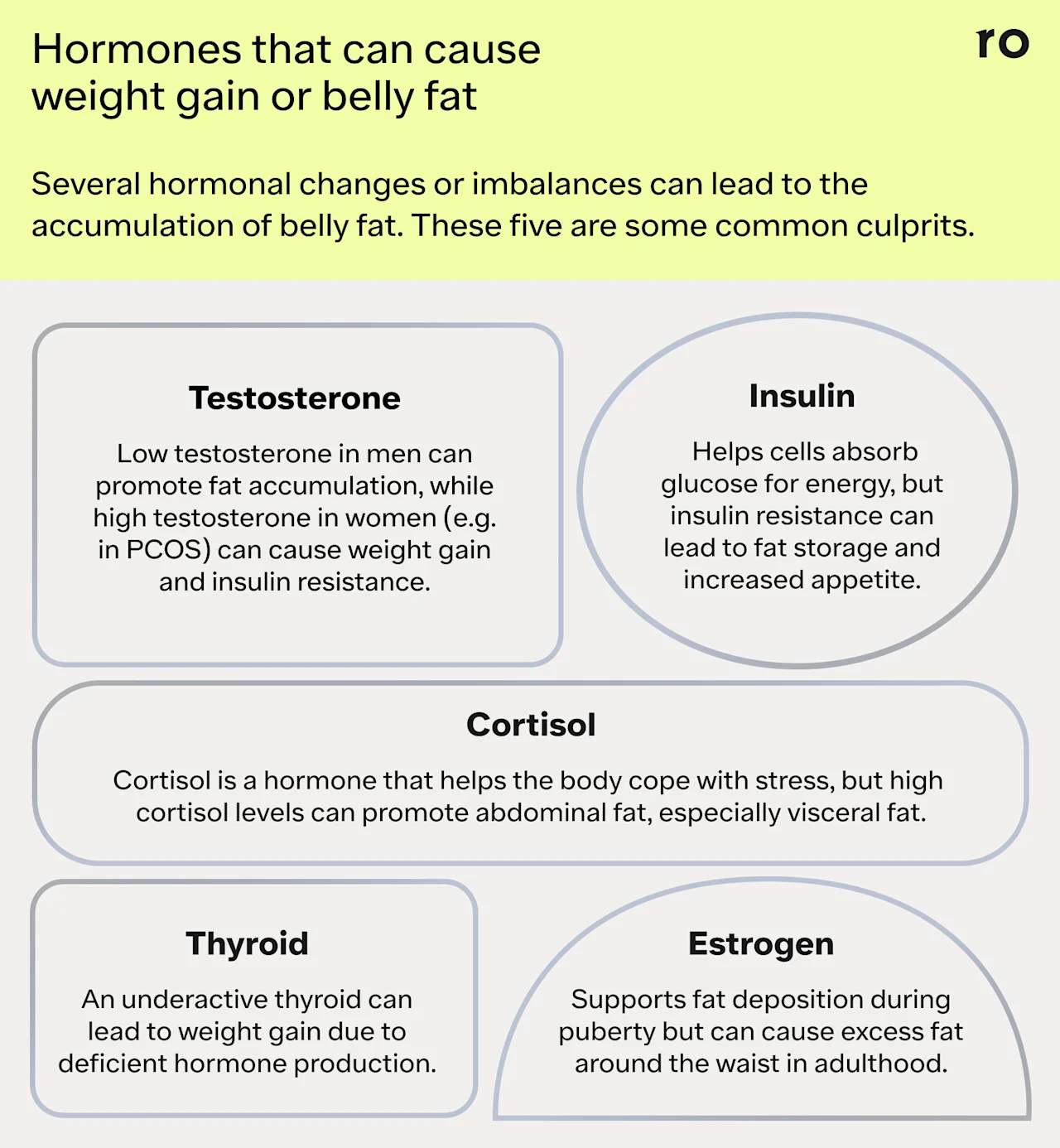

Hormone changes and imbalances

Changes or imbalances in these hormones may be associated with abdominal weight gain.

Cortisol

Cortisol is a steroid hormone that serves several important functions throughout your body, including regulating stress response, the inflammatory response, metabolism, and immune function. It can also contribute to the accumulation of abdominal fat, especially visceral fat.

A person might have a high cortisol level for several reasons, including chronic stress, exposure to environmental toxins, or even adrenal or pituitary gland tumors, which are rare.

One of the most common causes of dysregulated cortisol is chronic stress. Some types of occasional stress can be protective. For example, you’ve probably heard of the fight-or-flight response, a survival mechanism. When we have acute (immediate) stress—such as having to slam on the brakes to avoid a car accident—this system jumps into action and floods you with adrenaline and glucose so you can act fast.

A pile-up of small and big stressors throughout the day—including work deadlines, family responsibilities, relationship issues, financial woes, and more— can cause ongoing or chronic stress. We can also experience chronic stress from the ongoing psychological distress of past traumas.

When we have chronic stress, the body signals the adrenal glands to release cortisol. High or dysregulated cortisol can contribute to visceral fat because it encourages the body to store excess glucose as white adipose tissue in the abdominal area.

Cortisol can also “increase appetite, especially for comfort foods high in sugar, fat, and salt,” says Shiara Ortiz-Pujols, MD, director of obesity medicine at Northwell Staten Island University Hospital.

Dr. Ortiz-Pujols adds that high cortisol can decrease the quality of your sleep, contributing to more cortisol and an increased appetite (especially for ultra-processed foods) leading to weight gain. This type of weight gain may also be referred to colloquially as “cortisol belly.”

Insulin

Your pancreas releases the hormone insulin into your bloodstream in response to a rise in blood glucose (sugar). Insulin signals cells to uptake sugar from the blood to convert it to usable energy. However, in insulin resistance, cells can become less responsive to insulin signaling. High insulin (hyperinsulinemia) can drive fat storage, including visceral fat accumulation.

“Insulin signals fat cells to take up glucose from the bloodstream, which is then converted into triglycerides (fat globules) and stored as fat within the cell, especially around the waist,” Ortiz-Pujols says. “It also inhibits the breakdown of stored fat. This leads to a state in which the body preferentially stores excess sugar as fat, versus burning or using it for energy.”

Insulin may also increase appetite, especially for carbohydrates, she adds. This can create a complicated cycle of worsening insulin resistance and fat storage.

Estrogen

Estrogen is an important reproductive hormone for both the female and male body. The loss of estrogen during the menopause transition can lead to a loss of muscle tissue and an increase in fat tissue. High estrogen can also contribute to weight gain.

“Estrogen is important during puberty to promote fat deposition in the hips and thighs, which is an important part of development in adolescent females,” Ortiz-Pujols says.

“However, when there is too much estrogen, it promotes excessive fat deposition and weight gain. In adulthood, it contributes to fat deposition around the waist (belly fat), which is inflammatory and associated with various diseases.”

Estrogen deficiency in males is rare but can also cause fat gain. Likewise, high estrogen in males can cause weight gain by disrupting testosterone levels.

Testosterone

Testosterone is another reproductive hormone that’s crucial for both the female and male body. Low testosterone in males can cause an increase in fat accumulation, and high testosterone in females can cause weight gain.

“Testosterone levels are associated with lean body mass or muscle mass and lower body fat in men,” Ortiz-Pujols says. “Higher testosterone levels help men to maintain a healthy weight. As men age, their testosterone levels decrease and fat content increases. Increased fat deposition, especially around the waist, further decreases testosterone levels and decreased muscle mass, which is associated with slower metabolisms.”

Higher testosterone can also contribute to increased fat mass in the female body.

Thyroid

Thyroid hormones play important roles in regulating body weight, so an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism), which doesn’t produce enough hormones, can cause weight gain.

Leptin

This hormone produced in fat tissue helps tell your brain you’re full. However, too much leptin production (hyperleptinemia) can cause leptin resistance, in which the brain stops responding to leptin.

Leptin resistance can change how the body uses energy and can increase hunger and food intake, regardless of how much a person has eaten. Leptin resistance is a risk factor for weight gain, obesity, and other metabolic issues.

Health conditions that may impact hormonal balance

Some chronic health conditions can also impact hormonal balance and contribute to abdominal weight gain or a hormonal belly.

Cushing syndrome

Cushing syndrome occurs when the body produces too much cortisol. It can occur because of adrenal gland or pituitary gland tumors, both of which are rare, or because of long-term exposure to corticosteroid medications.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a chronic, systemic inflammatory condition in which endometrial-like tissue grows outside the uterus and releases molecules that cause inflammation and pain. This condition can lead to estrogen dominance, where estrogen is out of balance with other hormones, such as progesterone.

Although endometriosis doesn’t cause weight gain directly, it can lead to what’s called “endo belly,” a term to describe the bloating, distention, and discomfort associated with the condition.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism means the thyroid gland is underactive and does not produce enough thyroid hormones, which help regulate weight. This condition can lead to weight gain. The autoimmune disease Hashimoto thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease) is the most common cause of hypothyroidism.

Metabolic syndrome (MetS)

People with MetS have a group of risk factors that elevate their risk for chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes, which are tied to metabolic health.

Risk factors include high blood pressure, central obesity (excess visceral fat in the abdominal area), impaired fasting blood glucose, elevated triglycerides, and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL), aka “good” cholesterol. Typically, people receive a diagnosis of MetS when they have three out of these five risk factors.

MetS and imbalances in sex hormones are linked, with each potentially impacting the other. Additionally, MetS can disrupt signaling from adipokines (hormones secreted in fat tissue) and incretin hormones (secreted in the gut), such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Adipokines and incretin hormones help control hunger and satiety signals. Disruption in the secretion of adipokines and incretin hormones may lead to weight gain.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS is a condition that affects the ovaries. It’s associated with insulin resistance and high androgen levels, such as testosterone. “Women with PCOS have higher levels of testosterone and struggle more with weight, insulin resistance, and hormonal imbalances,” Ortiz-Pujols says.

Insulin resistance can lead to an overproduction of testosterone, which can then disrupt ovarian function. The increased testosterone can lead to weight gain.

Medications that can cause hormonal weight gain

Some medications can disrupt hormonal processes and lead to weight gain in general, or may specifically cause abdominal weight gain.

If you suspect a medication may be causing weight gain, do not stop taking it without consulting your doctor. They may be able to switch you to an alternative medication or find a way to help mitigate the drug’s side effects.

Antipsychotics

Some antipsychotic medications can increase the hormone leptin, which can interfere with hunger and satiety cues and lead to weight gain.

Corticosteroids

Some inflammatory conditions—such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, eczema, lupus, and more—may require regular or occasional use of corticosteroids to mitigate flare-ups. Long-term use of high-dose corticosteroids can lead to weight gain, especially around the midsection. In some cases, this long-term use can even cause Cushing’s syndrome.

Chemotherapy

Some chemotherapy drugs can also impact hormones in various ways, which may lead to weight gain.

Genetics

Genetics can play a role in some conditions—such as PCOS, endometriosis, hypothyroidism, and others—that are associated with hormonal imbalances.

Genetics can also be a factor in where we tend to gain fat (also called body fat distribution). Research suggests that 22% to 61% of fat distribution patterns can be attributed to genetics. This means you might be predisposed to carry more of your fat in your thighs, belly, abdomen, or other parts of the body.

Age and life stage

Age also contributes to hormonal, metabolic, and fat distribution changes. As we age, we tend to lose muscle mass and increase fat mass. In some cases, the increase in fat will show up around the midsection. Additionally, muscle tissue can help with insulin sensitivity, so when we lose muscle, our risk for insulin resistance may increase, which can also lead to fat gain.

The complex hormonal changes associated with menopause and andropause also impact how much and where we store fat.

Menopause

During the menopause transition, several changes in sex hormones occur. One of the most notable is the decline in estrogen. Estrogen is protective against insulin resistance, so the decline puts people more at risk for conditions such as prediabetes, type 2 diabetes, MetS, and more. Menopause also causes changes in adipokines. All of these factors can lead to an increase in belly fat.

Andropause

Andropause (or “male menopause”) is a term for describing the male decline of testosterone (hypogonadism) with age. This decrease in testosterone levels may be linked to obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, MetS, and more.

Weight gain can worsen the effects of hypogonadism because certain enzymes (such as aromatase) in fat tissue change testosterone into estrogen. This can cause further hormonal disruptions that can lead to additional weight gain.

Gut health and hormonal balance

Our gut health can also impact our hormones. We have bacteria and fungi living in our gut, and collectively they make up the gut microbiome. Additionally, the gut and brain talk to each other via what’s called the gut-brain axis. A disrupted gut microbiome can disrupt hormonal balance, which could impact hunger and fullness signals and contribute to obesity.

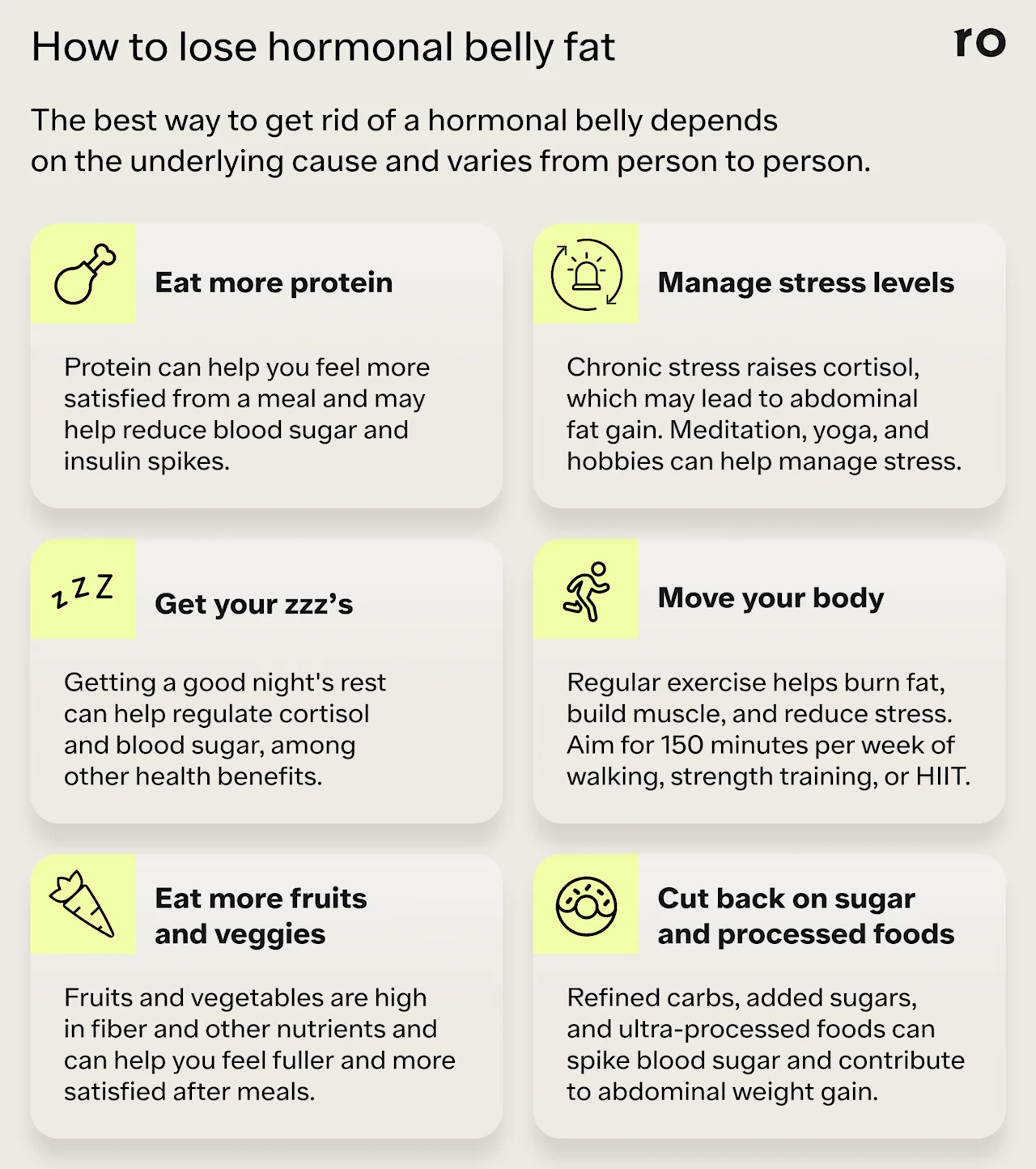

How to lose hormonal belly fat

The best way to get rid of a hormonal belly will likely depend on the underlying cause.

Your healthcare provider may prescribe medications or other therapies or may recommend lifestyle changes to help balance hormones or reduce belly fat and overall body fat.

Diet

Refining your diet may help to reverse or reduce abdominal weight gain. Here are a few tactics that can support weight loss and overall health:

Eat fewer processed foods. Ultra-processed foods tend to have higher amounts of added sugar, sodium, and additives, such as high-fructose corn syrup, which may contribute to weight gain.

Reduce added sugar and refined carbs. Sugar, especially from sweetened beverages, is linked to the accumulation of visceral fat. Refined carbohydrates, such as pastries, sugary drinks, and white bread, can also cause blood sugar and insulin spikes, driving fat growth.

Eat more fruits and vegetables. The fiber content in fruits and non-starchy vegetables (like broccoli, cucumbers, and carrots) feeds the microbiome, creating short-chain fatty acids, which help stimulate hormones that regulate hunger and fullness signals.

Include more protein in your diet. Protein helps you feel more satisfied and can help slow the absorption of glucose into the bloodstream, reducing blood sugar and insulin spikes. Protein also supports muscle. Good sources of protein include eggs, poultry, lean meats, and beans.

Exercise

Exercise can help reduce a hormonal belly in many ways, including reducing stress, and therefore cortisol, which can help reduce abdominal fat gain.

The recommended amount of exercise is 150 minutes per week (about 30 minutes a day five days a week), but the most important thing is to find a consistent routine that works for you. Even a short workout can offer a lot of health benefits.

Here are a few exercises to try that can help burn fat and build muscle:

Walking: Going for a short walk each day is an easy way to get moving. One simple strategy is to go for a walk shortly after a meal. Movement after eating can help reduce blood sugar spikes, which may help with insulin sensitivity.

High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT): These efficient workouts alternate short bursts of intense activity with active recovery—for example, 30 seconds of burpees followed by one minute of walking. Moderate to vigorous physical activity can help burn visceral fat and increase endurance.

Aerobic training: Alternate more intense workouts with lower-intensity exercises, such as cycling or swimming. These continuous aerobic training efforts can also help burn visceral fat.

Strength training: Incorporate resistance training at least twice per week, which can help build muscle and improve insulin sensitivity. Some moves to try might include bodyweight exercises like squats, push-ups, and planks.

Lifestyle changes

Several lifestyle changes may also help mitigate the symptoms of a hormonal belly. Two of the most important are reducing stress and getting adequate quality sleep:

Manage stress: Chronic stress increases cortisol, which can contribute to abdominal fat gain. Some ways to reduce stress may include meditation, breathwork, yoga, engaging in your favorite hobbies, or spending time with friends and loved ones.

Prioritize a good night’s sleep: Poor sleep can make you more insulin-resistant the next day. Sleep also helps regulate cortisol. Everyone has different sleep needs, but try to get at least seven to nine hours of quality sleep per night.

Medications

Your healthcare provider may also recommend medication to help treat your symptoms or manage an underlying health condition.

Some medications for hormone imbalances and related health conditions might include:

Metformin: This diabetes medication can help reduce insulin resistance and improve blood sugar control.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT): These treatments may be helpful for those with conditions like hypothyroidism, or who are undergoing the menopause or andropause transition.

Birth control: Oral birth control may be prescribed to help treat symptoms of PCOS and endometriosis.

GLP-1 medications: Injectable medications such as Ozempic and Mounjaro can help regulate blood sugar and may also promote weight loss for people with type 2 diabetes.

GLP-1 Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

Ozempic Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

Mounjaro Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

When to see a doctor about a hormonal belly

Talk to your healthcare provider if you’re experiencing weight gain that doesn’t respond to diet and exercise, or if you have other symptoms of a possible hormonal imbalance such as:

Abdominal pain

Fatigue

Changes in appetite

Mood swings

Menstrual cycle changes

Your provider may order blood or urine tests or recommend other diagnostic tools to help identify what’s causing your symptoms.

Bottom line

Nonmedical terms like “hormonal belly” and “cortisol belly” can describe abdominal weight gain due to possible hormonal dysregulation or imbalances.

Several factors can lead to abdominal weight gain, including age-related hormonal changes, stress, certain health conditions, and lifestyle factors.

The right treatment for a hormonal belly will depend on the factors causing it, but lifestyle interventions—such as diet, exercise, and stress management—and some medications may help.

If you’re concerned about abdominal weight gain or are experiencing symptoms of a possible hormonal imbalance, talk to your healthcare provider. They can help identify the underlying cause and recommend safe and effective treatments tailored to your unique needs.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

How do you fix a hormonal belly? Is it reversible?

Yes, you may be able to reduce or reverse a hormonal belly through lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise, with medications, or by treating any underlying conditions that contribute to weight gain.

What are the signs of a hormonal belly?

The main sign of a hormonal belly is unexplained abdominal weight gain. This may happen regardless of what you eat or how much you exercise. Other symptoms of a possible hormonal imbalance might include fatigue, changes in appetite, sleep problems, or mood swings.

What does a cortisol belly look like?

“Cortisol belly” is not a medical term but can describe an increase in abdominal fat that high levels of the stress hormone cortisol may bring on. However, not all midsection weight gain is a result of cortisol.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Chaker, L., Bianco, A. C., Jonklaas, J., et al. (2017). Hypothyroidism. Lancet, 390(10101), 1550-1562. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30703-1. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28336049/

Freeman, A. M., Acevedo, L. A., & Pennings, N. (2024). Insulin resistance. StatPearls. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29939616/

Gadekar, T., Dudeja, P., Basu, I., et al. (2018). Correlation of visceral body fat with waist-hip ratio, waist circumference and body mass index in healthy adults: A cross-sectional study. Medical Journal, Armed Forces India, 76(1), 41. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2017.12.001. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6994756/

Janochova, K., Haluzik, M., & Buzga, M. (2019). Visceral fat and insulin resistance - what we know? Biomedical Papers, 163(1), 19-27. doi: 10.5507/bp.2018.062. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30398218/

Ko, S. H. & Jung, Y. (2021). Energy metabolism changes and dysregulated lipid metabolism in postmenopausal women. Nutrients, 13(12),4556. doi: 10.3390/nu13124556. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8704126/

Leeners, B., Geary, N., Tobler, P. N., et al. (2017). Ovarian hormones and obesity. Human Reproduction Update, 23(3), 300-321. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw045.Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28333235/

Mittal, B. (2019). Subcutaneous adipose tissue & visceral adipose tissue. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 49(5),571. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1910_18. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6702693/

Pasquali, R. & Oriolo, C. (2019). Obesity and androgens in women. Frontiers of Hormone Research, 53, 120-134. doi: 10.1159/000494908. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31499497/

Rochira, V. & Carani, C. (2017). Estrogen deficiency in men. In: Simoni, M., Huhtaniemi, I. (Eds), Endocrinology of the Testis and Male Reproduction (pp. 797-828). Springer. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-44441-3_27

Rosen, E. D. & Spiegelman, B. M. (2014). What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell, 156(0), 20. doi: 10.3390/nu13124556. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8704126/

Rubinow, K. B. (2017). Estrogens and Body Weight Regulation in Men. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1043, 285–313. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-70178-3_14. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5835337/

Silveira, E. A., Vaseghi, G., de Carvalho Santos, A.S., et al. (2020). Visceral obesity and its shared role in cancer and cardiovascular disease: a scoping review of the pathophysiology and pharmacological treatments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(23), 9042. doi: 10.3390/ijms2123904. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7730690/

Thau, L., Gandhi, J., & Sharma, S. (2023). Physiology, cortisol. StatPearls. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/

van der Valk, E. S., Savas, M., & van Rossum E. F. C. (2018). Stress and obesity: are there more susceptible individuals? Current Obesity Reports, 7(2), 193. doi: 10.1007/s13679-018-0306-y. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5958156/

Waxenbaum, J. A., Reddy, V., & Varacallo, M. (2024). Anatomy, autonomic nervous system. StatPearls. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539845/