Key takeaways

The best way to lose belly fat involves a combination of regular exercise and a balanced diet.

It’s not possible to target fat loss to specific body parts. The best way to lose lower belly fat is to focus on strategies to reduce overall body fat.

Genetics, lifestyle, age, and certain health conditions can all lead to increased fat storage around the midsection.

Excess belly fat can increase your risk for health conditions like high blood pressure, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes.

Here's what we'll cover

Key takeaways

The best way to lose belly fat involves a combination of regular exercise and a balanced diet.

It’s not possible to target fat loss to specific body parts. The best way to lose lower belly fat is to focus on strategies to reduce overall body fat.

Genetics, lifestyle, age, and certain health conditions can all lead to increased fat storage around the midsection.

Excess belly fat can increase your risk for health conditions like high blood pressure, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes.

Belly fat is an issue that affects people of all backgrounds. While our bodies need some fat for essential functions, research shows that excess abdominal fat can increase the risk of health conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and several cancers.

Understanding the connection between belly fat and overall health is important for taking the first step toward managing it effectively.

Whether you're looking to improve your general health, reduce disease risk, or change your physical appearance, read on for evidence-backed strategies for how to lose belly fat.

Rx weight loss with Ro

Get access to prescription weight loss medication online

What is belly fat?

Fat, or adipose tissue, is a type of connective tissue found throughout the body that supports various functions. For example, fat cells store energy and help to regulate metabolism, hunger, and satiety (how full and satisfied you feel after eating).

When we talk about body fat, we typically talk about subcutaneous and visceral fat. Subcutaneous fat (the fat you can pinch) lies right under the skin. Deeper inside the abdomen is visceral fat, which wraps around vital organs like the liver, pancreas, and intestines.

Both types are normal and necessary, but excess visceral fat can lead to health complications like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, and cognitive decline. A waist circumference over 35 inches can indicate an unhealthy amount of abdominal fat for women. For men, it’s 40 inches.

Sustainable approaches to fat loss

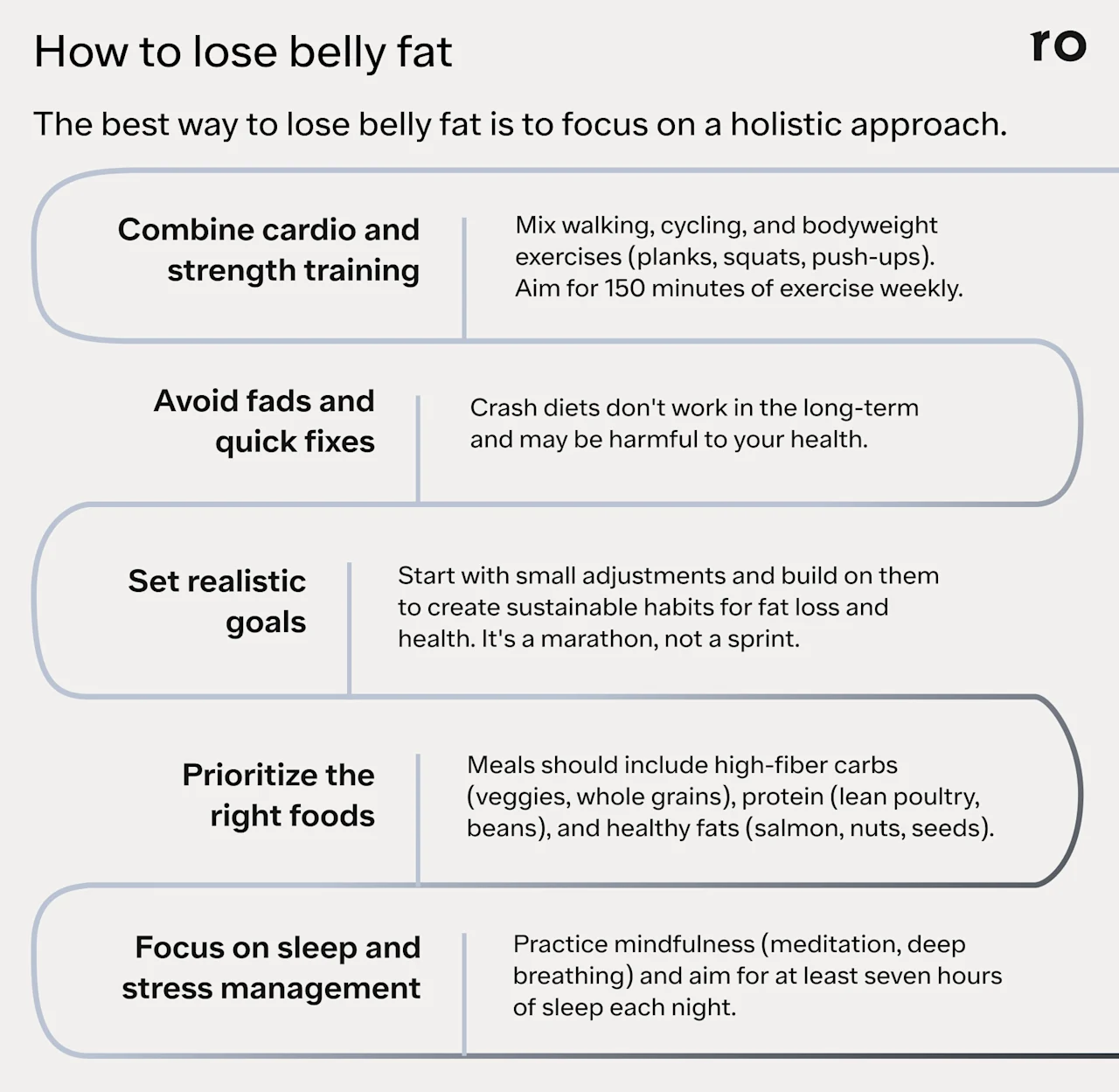

First things first: it’s not possible to target fat loss to specific body parts. The best way to lose belly fat is to focus on strategies to reduce overall body fat.

This requires a comprehensive approach that combines nutrition, regular physical activity, stress management, and adequate sleep. As you lose body fat overall and increase muscle, you may also see a reduction in belly fat.

The best ways to lose fat aren’t super exciting. No complicated fitness routines, high-tech equipment, or “magic” supplements are going to unlock some hidden secret to rapid (and maintained) fat loss. To get the best results, it’s about consistency.

“If you want to lose weight and actually keep it off, you need to build healthy habits that support that,” says Alyssa Pacheco, RD and founder of The PCOS Nutritionist. “When it comes to weight loss, slow and steady wins the race."

Set realistic goals

Quick-fix solutions and crash diets can be harmful to your health, and don’t set you up for sustainable weight loss. Pacheco recommends setting measurable goals that you can adjust over time.

“Instead of setting lofty weight loss goals, it may be easier to set smaller goals, then re-evaluate once you hit that original goal,” she says. She adds that it’s important to adjust your expectations around a timeline to lose weight safely.

“One to two pounds per week is typically considered to be a safe weight loss goal,” Pacheco says. She adds that slow weight loss is usually sustainable, and can make rebound weight gain less likely.

Balanced nutrition vs. crash diets

When considering diet and nutrition for weight loss, Pacheco stresses that the goal should be to make manageable changes to your eating habits that create a solid foundation for health.

Your meals should ideally include a source of:

High-fiber carbohydrates (carbs) like oats, beans, and sweet potatoes

Protein like poultry, eggs, and lean meats

Healthy fats like salmon, avocadoes, and nuts

She says that this combination of foods can keep blood sugar levels more stable, which helps you feel full for longer periods and can aid in weight loss.

Move your body

Regular exercise is crucial for fat loss and overall health, but you don’t necessarily have to join a gym or do complicated workouts to see results.

Aim for 150 minutes of exercise per week, or roughly 30 minutes five times each week. If that feels difficult, start small, keep it simple, and build from there—even a few minutes of movement each day can add up.

“You can’t target where you lose weight, but doing both cardiovascular exercises and strength training is best for overall fat burning and health,” says Chris Mohr, PhD, RD, and fitness and nutrition advisor at Fortune Recommends.

How to get rid of belly fat: 15 expert-backed strategies

These tried-and-true methods for fat loss aren’t just about short-term changes—success in reducing belly fat requires consistent, long-term behavioral changes that you can maintain over time.

Both Pacheco and Dr. Mohr recommend starting with small, manageable adjustments and gradually building on them to create sustainable habits that support your weight loss goals.

Get your heart rate up with cardio

Cardiovascular exercise is any physical activity that elevates your heart rate and breathing for a sustained period while engaging large muscle groups. Cardio exercises are great for improving your heart health, stamina, and overall endurance. It can also help burn calories and increase lung capacity.

Start with a brisk 20-minute walk a few times a week, and then gradually build up to longer or faster sessions. Shorter exercise sessions count, too—even a little movement each day can have a positive effect on your health.

Try: Running, cycling, brisk walking, or swimming

Try high-intensity interval training (HIIT)

HIIT involves alternating between short bursts of intense exercise and short rest periods. HIIT workouts are efficient— you can burn more calories, boost your heart health, and build muscle in a short amount of time. HIIT workouts can involve a variety of cardio and bodyweight exercises like squats, sprints, burpees, jumping jacks, and mountain climbers.

Try: Aim for 30 seconds of intense activity, followed by a minute of active recovery. A beginner-friendly example would be sprinting or doing jumping jacks for 30 seconds, then walking for one minute. Repeat that for 15–20 minutes. You can also rotate exercises like squats, burpees, or lunges to create a circuit.

Pump some iron

Strength training uses resistance to build muscle, strength, and endurance. This type of exercise can improve bone density and increase muscle mass, which can in turn increase your resting metabolic rate and help your body burn more calories even when you’re not exercising. You can use bodyweight, resistance bands, or free weights to do strength training exercises.

Try: A starter routine might include bodyweight exercises like squats, lunges, bicep curls, push-ups, and planks, performed in three sets of 10-12 reps, two to three times per week.

Work your core

Core exercises target the deep muscles in your abdomen, lower back, hips, and pelvis. Core work is valuable for building strength and improving posture.

Try: Incorporate core exercises like planks, dead bugs, and Russian twists into your strength training routine two to three times per week.

Go for a walk

There’s no magic number for the amount of steps you should take each day, but the health benefits of walking are numerous. In addition to supporting weight loss, walking can boost your mood, reduce joint pain, improve blood sugar control, and lower your risk for heart disease. In combination with more strenuous exercise, daily walking can boost your fat loss goals.

Try: Start with a 10-minute walk every day and gradually increase the time as you are able. You may even want to try out a pedometer or app that can help track your steps to stay motivated.

Sample beginner workout for fat loss

You don’t need a complicated routine to get in a good workout. Keep it simple and focus on consistency—even short bouts of regular exercise can help you build muscle, lose fat, and boost your overall health.

Monday: 20 minutes of walking/10 minutes of strength training

Wednesday: 15 minutes of HIIT, followed by 5 minutes of stretching or yoga to recover

Friday: 20 minutes of strength training/20 minutes of walking or light jogging

Alternate workout and rest days to give your body time to recuperate—with any workout regimen, recovery is important (and when your body reaps the most benefit). Active recovery is even better. On rest days, aim for a short 15-minute walk to keep your body moving.

Eat more protein

Getting enough protein in your diet can help support weight loss in a variety of ways: it can help you feel fuller and more satisfied from meals, boost metabolism, and also help build and maintain muscle mass. Protein needs will vary based on several factors such as height, weight, activity level, and medical history. The USDA recommends that 10-35% of total calories come from protein, with research suggesting that 25-30g of protein per meal can be effective for weight loss.

You can use the USDA’s MyPlate Plan tool to calculate how many grams of protein you should eat each day based on your age, weight, activity level, and other factors.

Try: Some good sources of protein include seafood, meat, poultry, eggs, beans, and lentils.

Focus on fiber

Fiber is an indigestible carb that moves through your digestive system very slowly, creating a feeling of fullness. Some evidence suggests that a fiber-rich diet can aid in the prevention of obesity and type 2 diabetes, among other health conditions, due to its effect on regulating blood sugar and satiety.

The National Academy of Medicine gives these recommendations for daily fiber intake:

21 grams for women older than age 50

25 grams for women aged 50 or younger

30 grams for men older than age 50

38 grams for men aged 50 or younger

Try: Incorporate more fiber-rich foods (especially soluble fiber) into your diet. This includes foods like apples, oats, beans, peas, whole grains, and Brussels sprouts.

Cut down on processed foods

Processed foods can be convenient when you need a quick meal or snack, but over time research suggests that these foods—which are high in saturated fats, sodium, and sugar—can lead to overeating and weight gain.

Try: As much as possible, cook meals at home instead of eating out. Meal planning for the week and prepping snacks can save time and ensure you have nutritious food on hand.

Don’t skip meals

“I recommend making sure that you're eating three meals each day and not going more than four to five hours without eating,” Pacheco says. “This approach helps stabilize blood sugar levels and prevent overeating.”

Try: Eating smaller, more frequent meals or having healthy snacks on hand.

Eat in a calorie deficit

A slight calorie deficit may be necessary for weight loss, but that doesn’t mean you should skip meals or cut out entire food groups. Pacheco notes that several online calculators can provide a rough idea of your calorie needs per day, but notes that these are just estimates. “The only true way to determine your calorie needs is direct calorimetry, which isn’t readily available for public use,” she says.

Balanced nutrition is important when eating in a caloric deficit to ensure that you’re getting the necessary nutrients and that you have enough energy throughout the day.

Try: Subtracting 250-500 calories per day may be effective for sustainable weight loss. Online calculators and macros-counting apps can help you figure out your daily calorie needs. It can also be helpful to work with a skilled dietician to create a balanced meal plan that supports your weight loss goals.

Be mindful to manage stress

Chronic stress triggers the release of cortisol, the "stress hormone," which can promote belly fat storage and make it harder to lose weight—in addition to a host of other potential health issues. Mindfulness techniques may help with stress management.

Try: Meditation, yoga, or deep breathing exercises may help you cope with stress and promote overall relaxation.

Get your zzz’s

Quality sleep is also critical for weight loss. Research shows that people who consistently get less than seven hours of sleep per night tend to accumulate more visceral fat. Not sleeping enough can disrupt hunger hormones, increase cravings, and make it harder to stick to healthy eating habits. Assess your sleep hygiene to see what changes might support a better night’s rest.

Try: Stop drinking caffeine at least eight hours before bedtime, cut back on alcohol, limit screens and blue light before bedtime, or use a sleep mask or white noise machine to create a better sleep environment.

Stay hydrated

Drinking enough water can help maintain a healthy metabolism, reduce false hunger signals, and support your body's fat-burning processes. Individual water intake needs vary based on factors like age and activity level but aim for an average of about 125 ounces of water per day for men and 91 ounces per day for women.

Try: Keep a water bottle with you. Better yet, find a water bottle that shows the amount in ounces on the side so you can keep track of your intake throughout the day.

Drink less alcohol

“Excessive alcohol adds to your calorie intake without adding any nutritional value, interferes with fat burning, and leads to increased belly fat storage,” says Pacheco. Moderate to excessive alcohol use looks different for different people, but is generally considered eight or more drinks for women and 15 per week for men.

Try: Designate a few alcohol-free days per week. You can also swap out your favorite alcoholic beverage with a mocktail or soda water.

Look beyond the scale

The health benefits of fat loss are more than just a number on a scale. Tracking non-weight-related gains can motivate you to stick to healthy habits. Some non-scale wins might include increased energy levels, better sleep or blood pressure, boosted mood, or that your clothes fit better.

“You may find that your ultimate goals change during your weight loss journey,” Pacheco says. “Perhaps you'll find that you feel really great after losing a certain amount of weight, even though it's not the final number you had in mind.”

Try: Keep a journal of your progress to document how you feel and celebrate your wins.

What causes belly fat?

The accumulation of belly fat can stem from multiple factors that affect how the body stores and processes fat. These can include genetics, lifestyle elements like diet and activity, certain health conditions, and age.

Diet and lifestyle

Nutrition, access to whole foods, and a balanced diet can impact belly fat and overall health. Diets high in processed foods and sugar can directly contribute to belly fat accumulation.

A lack of regular physical activity can prevent the body from effectively burning stored fat. Inadequate sleep and chronic stress may trigger hormonal changes that can cause weight gain around the midsection and make it harder to lose body fat overall.

Hormonal changes

Your hormonal balance at different ages and life stages can significantly impact where and how fat is stored. For example, women may experience increased belly fat during menopause due to declining estrogen levels. Men may see similar changes with age-related testosterone reduction. Postpartum hormonal fluctuations may also lead to persistent abdominal fat storage.

Other health conditions

Certain health conditions can interfere with the body’s normal metabolic processes and promote belly fat storage, among other health issues.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) affects hormone levels and insulin sensitivity, which can make weight loss more challenging for many women.

Cushing's syndrome and hypothyroidism can impact how the body processes and stores fat.

Type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome can cause insulin resistance, which can make the body prone to storing fat in the abdominal area.

Sex and genetics

The fundamental principles of losing belly fat apply to everyone. However, men and women face different physiological challenges. Women tend to have a higher body fat percentage and less muscle mass than men. Body fat distribution is also different for men and women, too—men accumulate fat around the midsection, while women accumulate body fat in the thighs and buttocks.

Research suggests that while men are more likely than women to accumulate visceral fat, they can lose belly fat more quickly than women.

Genetics plays a role in body fat distribution as well. Research shows that certain ethnic populations may be predisposed to accumulating visceral fat. According to this study comparing body fat distribution among people with European, African, and Asian ancestries, “[fat distribution] patterns vary across ethnic groups independent of obesity. Asians have more and Africans have less visceral fat compared with Europeans,” which can impact body mass index (BMI) as well as risk for weight-related health complications like high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes.

Age

In addition to hormonal changes, several factors can contribute to increased belly fat storage as we age.

Muscle mass naturally decreases with age, which can lower the body’s metabolic rate and can make it easier to store fat.

Older adults are often less physically active, which can lead to increased body fat and reduced muscle mass.

Insulin resistance (when the body doesn’t respond to insulin) can increase with age, which can lead to dysregulated blood sugar, increased food cravings, and weight gain.

How long will it take to lose body fat?

That answer varies and depends on multiple factors, such as a person’s age, activity level, diet, and underlying conditions. Sustainable fat loss is a gradual process, and losing belly fat requires setting realistic expectations for yourself and making healthy habits part of your routine.

Quick-fix solutions might promise faster results, but experts agree that a slow-and-steady approach leads to lasting changes and better long-term health outcomes.

“You might start to see minor changes in a few weeks, but significant and lasting results often take months,” says Dr. Mohr.

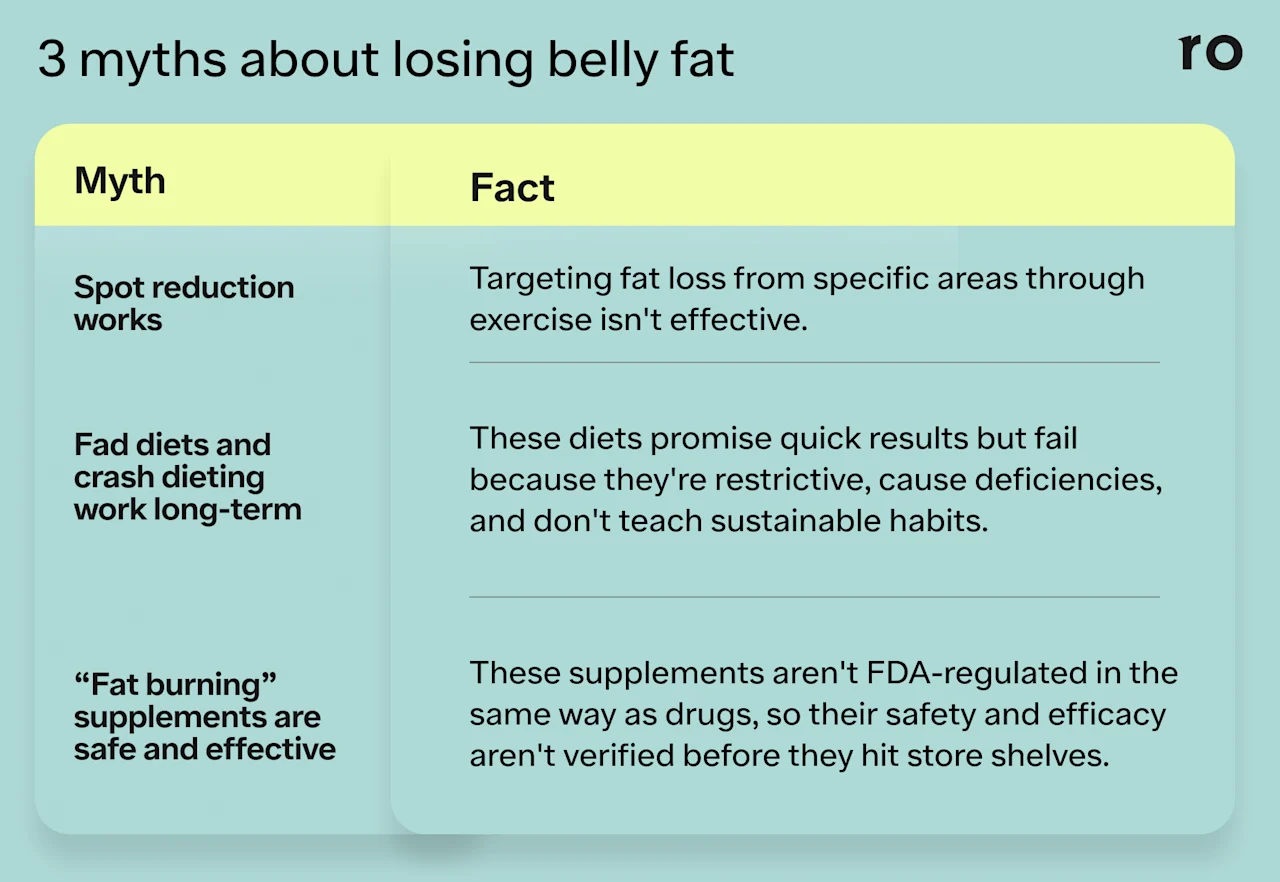

3 myths and misconceptions about losing belly fat

Myth 1: Spot reduction works

Targeting fat loss from specific areas through exercises isn’t effective. Core exercises like crunches or planks can strengthen abdominal muscles, but they don't specifically burn belly fat.

“Spot reduction is a myth because when you exercise, you don't just burn fat from the area you're working out,” says Dr. Mohr. “Your body breaks down fat from all over and uses it for energy as needed, to meet the energy demands.”

Myth 2: Fads and crash diets work long-term

These diets promise quick results, but they often fail for several reasons:

They sometimes eliminate entire food groups, which can cause nutritional deficiencies.

They don't teach sustainable, healthy eating habits.

They're too restrictive to maintain long-term, which can lead to rebound weight gain.

For example, you may see a lot of lose-weight-quick diets that significantly reduce or cut out carbs. Pacheco explains why this isn’t ideal for sustainable results. “Cutting out carbs is a common way to lose weight quickly; however, people are usually losing water weight first, not fat loss,” she says. “Carbs are your body's preferred fuel source.”

“When you stop eating carbs, your body is searching for carbs to use as energy and it will break down a stored form of carbohydrate in your muscles called glycogen,” Pacheco adds. “Your muscles are kind of like a sponge, holding onto a lot of water. When your body breaks down that glycogen, a lot of that water weight goes with it—which is the quick weight loss that people usually see.”

If carbs are reintroduced into the diet, the body restores the lost glycogen and water, which can lead to a rapid regain.

Myth 3: “Fat burning” supplements are safe and effective

Weight loss supplements are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the same way as over-the-counter or prescription drugs, which means their safety and effectiveness aren't verified before they hit store shelves.

Despite marketing claims, there’s little evidence that these supplements can promote weight loss, and because the ingredients and formulations are not regulated there’s potential for serious harm when using these products. Even natural-sounding ingredients can be dangerous in concentrated supplement form, potentially causing serious side effects and dangerous interactions with medications.

Bottom line

The best way to lose belly fat is a combination of habits that include regular exercise, balanced nutrition, and quality sleep.

To get rid of belly fat, aim for 150 minutes of exercise per week (such as cardio and strength training), increase your protein and fiber intake, stay hydrated, and prioritize sleep and stress management.

You can’t target fat loss to a specific area or body part. The best way to reduce belly fat is to focus on strategies that reduce overall body fat.

Fad diets or methods promising rapid weight loss aren’t sustainable and often lead to rebound weight gain. A safe weight loss goal is one to two pounds per week.

Weight loss results are individual and sustainable fat loss can take time. Be patient with your progress and focus on making lasting lifestyle changes rather than seeking temporary solutions.

You may also want to seek out expert help as you start the journey to losing belly fat and improving your overall health. There are 250,000+ weight loss members at Ro. Connect with a healthcare provider today to create a custom plan for your health goals.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

What burns the most stomach fat?

A combination of regular strength training and cardio exercise, boosting protein and fiber intake, stress management, and adequate sleep is most effective for reducing belly fat. No single approach works best in isolation.

What exercises burn the most belly fat?

Cardio, strength training, and HIIT provide the most effective approach to fat loss. Remember that spot reduction isn't possible—focus on exercises that work all your major muscle groups to reduce overall body fat.

How can I lose belly fat really fast?

While quick fixes might seem appealing, sustainable fat loss takes time. Aim for one or two pounds of overall weight loss per week through healthy lifestyle changes.

How can I reduce my tummy in seven days?

Significant fat loss in just one week isn't realistic or good for your health. Focus on sustainable lifestyle changes for long-term success.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Armstrong, L. E. & Johnson, E. C. (2018). Water Intake, Water Balance, and the Elusive Daily Water Requirement. Nutrients, 10(12), 1928. doi: 10.3390/nu1012192. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6315424/

Chang, A. M. & Halter, J. B. (2003). Aging and insulin secretion. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 284(1), E7-E12. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2002. Retrieved from https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpendo.00366.2002

Christensen, P., Meinert Larsen, T., Westerterp-Plantenga, M., et al.(2018). Men and women respond differently to rapid weight loss: Metabolic outcomes of a multi-centre intervention study after a low-energy diet in 2500 overweight, individuals with pre-diabetes (PREVIEW). Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism, 20, 2840–2851. doi: 0.1111/dom.13466. Retrieved from https://dom-pubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/dom.13466

Covassin, N., Singh, P., McCrady-Spitzer, S. K., et al. (2022). Effects of experimental sleep restriction on energy intake, energy expenditure, and visceral obesity. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 79(13), 1254-1265. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.01.038. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35361348/

Fridén, M., Kullberg, J., Ahlström, H., et al. (2022). Intake of Ultra-Processed Food and Ectopic-, Visceral- and Other Fat Depots: A Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 774718. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.774718. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/nutrition/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.774718/full

Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., et al. (2019). Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metabolism, 30(1), 67-77. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008. Retrieved from https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(19)30248-7

Leidy, H. J., Clifton, P. M., Astrup, A., et al. (2015). The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 101(6), 1320S–1329S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.084038. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25926512/

Luo, L. & Liu, M. (2016). Adipose tissue in control of metabolism. The Journal of Endocrinology, 231(3), R77–R99. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0211. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7928204/

Nauli, A. M. & Matin, S. (2019). Why Do Men Accumulate Abdominal Visceral Fat? Frontiers in Physiology, 10(1486), 1-10. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01486. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2019.01486/full

Quagliani, D. & Felt-Gunderson, P. (2016). Closing America's Fiber Intake Gap: Communication Strategies From a Food and Fiber Summit. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 11(1), 80–85. doi: 10.1177/1559827615588079. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6124841/

Singh, B. & Maurya, N. K. (2024). The Cortisol Connection: Weight Gain and Stress Hormones. Archives of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 8, 009-013. doi: 10.29328/journal.apps.1001050. Retrieved from https://www.pharmacyscijournal.com/articles/apps-aid1050.php

So-Yun, Y., Steffen, L. M., Terry, J. G., et al. (2020). Added sugar intake is associated with pericardial adipose tissue volume. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 27(18), 2016–2023, doi: 10.1177/2047487320931303. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/eurjpc/article/27/18/2016/6125545

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Retrieved from https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans_2020-2025.pdf

Waddell, I. S. & Orfila, C. (2022). Dietary fiber in the prevention of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases: From epidemiological evidence to potential molecular mechanisms. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 63(27), 8752–8767. doi: 10.1080.10408398.2022.2061909. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10408398.2022.2061909

Wilkinson, D. J., Piasecki, M., & Atherton, P. J. (2018). The age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function: Measurement and physiology of muscle fibre atrophy and muscle fibre loss in humans. Ageing Research Reviews 47, 123-132. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2018.07.005. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S156816371830134X

Xiaoran, L., Yanping L., Tobias, D. K., et al. (2018). Changes in Types of Dietary Fats Influence Long-term Weight Change in US Women and Men. The Journal of Nutrition 148(11), 1821-1829. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy183. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022316622109387