Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Acne, the bane of adolescence, can (unfortunately) affect adults as well. But the good news for you and your teen counterparts is that acne treatments have come a long way. By teaming up with a dermatologist (skin specialist), you can work to develop a treatment plan that is right for you. Read on to learn more about your acne treatment options.

Treatments for acne

The good news if you suffer from acne is that many effective treatment options for adult acne exist, including:

Topical treatments

Oral treatments

Procedures

Natural treatments

Not every treatment works for every person, and it may take time to find the best option for you. Some therapies are available over-the-counter (OTC), while others may require a prescription or a procedure.

Acne facial remedies can vary based on your age and the severity of your acne; you may need spot acne treatments or even acne scar treatments. And it may take several weeks before you see results. Talk to your dermatologist or healthcare professional to discuss the risks and benefits before starting any of these treatments.

Topical acne treatments

Topical medications can be applied directly to the skin both to treat an outbreak and to prevent new acne from forming. They may be used by themselves or in combination with other drugs.

Benzoyl peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide works by attacking the C. acnes (formerly called P. acnes) bacteria that live on the skin and can cause acne. By decreasing the presence of this bacteria, benzoyl peroxide can improve your acne, sometimes as soon as five days after starting it. Benzoyl peroxide is available in strengths from 2.5% to 10% and as washes, foams, creams, or gels. Sometimes it is combined with other topical or oral treatments. Side effects include skin irritation, staining or bleaching of fabric, and allergic reactions (Zaenglein, 2016).

Topical antibiotics

Topical antibiotics work not only by attacking the bacteria that contribute to acne but also because many of these drugs have anti-inflammatory effects. They are often used in combination with benzoyl peroxide because using topical antibiotics alone can lead to antibiotic resistance. The most commonly used antibiotics are clindamycin and erythromycin. In general, most people tolerate these medications well (Zaenglein, 2018).

Topical retinoids

Topical retinoids are medications made from vitamin A (retinol). Studies have shown that retinoids effectively treat acne by unclogging pores, decreasing oil production, and reducing the inflammatory response. They are useful in both resolving acne eruptions and helping you maintain clear skin (Yoham, 2021).

The three most commonly used topical retinoids are tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. Side effects include dryness, peeling, irritation, and redness. Retinoids can also make you more sensitive to the sun and more likely to get a sunburn. Therefore, experts recommend applying retinoids at night after washing your face. You should also use a broad-spectrum SPF 30+ sunblock in the morning. (Yoham, 2020; Zaenglein, 2018; Guerra, 2021)

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), some topical retinoids are pregnancy category C. This means that there aren’t good studies in pregnant women, and retinoids should only be used during pregnancy if the potential benefit to the mother outweighs the potential risk to the fetus (Yoham, 2021).

Azelaic acid

Azelaic acid works to unclog pores, kill skin bacteria, and improve inflammation. It can be used alone or in combination with topical antibiotics. Side effects include skin discoloration and irritation (Zaenglein, 2018; Zaenglein, 2016).

Salicylic acid

Some studies show that salicylic acid helps to unclog pores, but clinical trials are limited (Zaenglein, 2018).

Dapsone

Dapsone 5% gel helps to reduce the inflammation in acne. How it works is not well understood, but it seems to work better in women than in men. Side effects include redness, dryness, and orange-brown skin discoloration that can be washed off. It is pregnancy category C (Zaenglein, 2018; Zaenglein, 2016).

Oral acne medications

Oral treatments are used for people with moderate-to-severe acne that does not respond to topical medications. Oral therapies are pills taken by mouth and have effects throughout the body (as opposed to topical treatments that are applied directly at the site of acne).

Because of this full-body effect, oral treatments tend to have more side effects than topical (skin only) medications and usually aren’t the first choice for acne treatment. Oral medications include antibiotic pills, oral birth control, isotretinoin, and antiandrogen agents like spironolactone.

Oral antibiotics

Oral antibiotics can help people with moderate to severe acne. Most providers typically try the tetracycline class of antibiotics first; this class includes doxycycline and minocycline.

Tetracyclines have both antibiotic and anti-inflammatory properties that make them useful in acne treatment. Side effects can include increased photosensitivity, upset stomach, diarrhea, and skin discoloration. Pregnant people and children under eight years old should not use tetracyclines (Zaenglein, 2016; Zaenglein, 2018).

Other antibiotics, like erythromycin and azithromycin, are also sometimes used for acne in people who cannot use tetracyclines. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, and an upset stomach (Zaenglein, 2016; Zaenglein, 2018).

Oral antibiotics should be used for the shortest time possible to prevent antibiotic resistance. Also, these medications are often combined with other treatments like benzoyl peroxide products or retinoids to decrease the risk of antibiotic resistance (Zaenglein, 2016; Zaenglein, 2018).

Isotretinoin (brand name Accutane)

Isotretinoin is a popular oral prescription retinoid medication for severe acne. This drug treats skin bacteria, clogged pores, increased oil production, and inflammation—all of which contribute to acne formation (Fallah, 2021).

Isotretinoin can treat severe and moderate acne that has not responded to other therapies or is causing scarring and psychosocial distress, like depression, embarrassment, etc. Treatment usually takes 4–5 months or longer. It is imperative that women of child-bearing age avoid pregnancy before or during treatment with isotretinoin because the drug has a high risk of birth defects. Women need to use two forms of contraception during therapy and must be willing to have regular pregnancy tests (Pile, 2021).

Other possible side effects include dry skin, eye inflammation, dry eyes, dry mouth and nose, skin that is more sensitive to sun and dryness, mood changes, joint or muscle pains, liver problems, and others (Pile, 2021).

Birth control pills

Birth control pills can help clear acne in women by restoring the balance of estrogens and other hormones. Specifically, combined oral contraceptives, which are birth control pills that have both estrogens and progestins, are the most helpful with acne. Birth control pills help treat acne by decreasing androgen levels in the skin.

Four combined oral contraceptives are FDA-approved for treating acne in women (Zaenglein, 2018):

Estrogen and norgestimate (brand name Ortho Tri-Cyclen)

Estrogen and norethindrone (brand name Estrostep)

Estrogen and drospirenone (brand name Yaz)

Estrogen and drospirenone and levomefolate (brand name Beyaz) .

It may take a few months before you see any effects on your acne after starting this therapy. Birth control pills should only be used by women who are not pregnant and do not want to become pregnant. The most common side effects include weight gain, breast tenderness, and breakthrough bleeding. Rarely, more serious adverse effects like blood clots and heart attacks may occur in some women. Because of these risks, birth control pills are not recommended for women over 35 who smoke (Cooper, 2021).

Spironolactone

Spironolactone is another medication that affects hormone levels in women, which can be useful for women with hormonal acne. It works by blocking androgens in the skin. Spironolactone is generally not used to treat acne in males because it can lead to breast development.

Side effects include painful periods, irregular periods, breast tenderness, and breast enlargement. Also, spironolactone is a diuretic, so you may find that you need to urinate more often. It can affect your potassium levels, so you should avoid taking any potassium supplements while on spironolactone. Lastly, spironolactone is not recommended for pregnant women (Zaenglein, 2018).

Procedures for treating acne

Studies have looked at several procedures that can help with acne. While the data is limited, there may be some benefit to certain procedures your dermatologist can offer.

Steroid injections

Nodular acne (acne that forms cysts deep in the skin) or cystic acne treatments may include a steroid medication injection directly into the nodules to help them resolve. This therapy is effective and commonly used for people with larger acne nodules that do not respond to other treatments. Improvement in appearance and pain occurs relatively quickly with these injections. Side effects may include thinning skin in the area of the injection (Zaenglein, 2016).

Chemical peels

Chemical peels are minimally invasive procedures that may help with your acne. They work by using harsh chemicals to remove the outermost layer of skin, or chemical peels can go deeper, depending on the strength of the peel. Chemical peels typically use solutions of salicylic acid, glycolic acid, or retinoic acid. They may improve the appearance of acne and acne scars.

Chemical peels can be a face or back acne treatment, but are more prone to cause scarring if used on the neck or chest. Depending on the strength of the peel, side effects can include changes in skin coloration, infection, and scarring (Castillo, 2018).

Extractions

Whiteheads and blackheads that don’t improve with medical therapy can be removed by your provider using special instruments. Side effects include potential scarring at the extraction site.

Lasers/light therapy

There are several different light therapies or laser treatments for acne, including pulsed dye laser, CO2 laser, photodynamic therapy, radiofrequency, and more. The data is limited, and more studies are needed to determine if these treatments work (Zaenglein, 2018).

Natural acne treatments

Many at-home or natural acne treatments are out there, but there is limited scientific data regarding these remedies. Some remedies are aimed at the causes of acne, like decreasing stress, staying hydrated to keep your skin healthy, and using sunscreen to avoid sun damage.

Studies have also looked at the role that diet may play in acne. Some studies show that following a low-glycemic index diet may improve acne. Low glycemic index foods include most fresh vegetables, some fresh fruits, beans, lentils, and whole grains (Dall'Oglio, 2021).

Everything you eat changes the amount of sugar (glucose) in your blood to some degree. Meals that cause a high spike in blood sugars have a high-glycemic index, whereas low-glycemic index foods do not raise your blood sugar too much. Some research lon how acne changes when adjusting the diet has found that eating foods with a lower glycemic index may improve acne (Dall'Oglio, 2021).

Other studies suggest that dairy products may be linked to an increased risk of getting acne. Theories include the idea that milk proteins may trigger hormones and growth factors in the body that increase your likelihood of developing acne. So potentially avoiding dairy may improve your acne. But scientists need more research looking at the relationship between diet and acne before making definitive diet recommendations (Juhl, 2018).

Lastly, limited data suggest that tea tree oil, zinc supplements, probiotics, and fish oil may improve acne. More research is needed regarding natural therapies (Zaenglein, 2016).

What is acne?

Acne (acne vulgaris) is the medical term for those annoying pimples, papules, whiteheads, blackheads, etc. that most people associate with puberty and the awkward teenage years. But acne can happen in your 30s, 40s, 50s, and even later. When it occurs after age 20–25, it’s called adult acne. As the most common skin problem in the United States, acne affects 40–50 million people at any given time, and nearly everyone has acne at some point in their lives (AAD, n.d.).

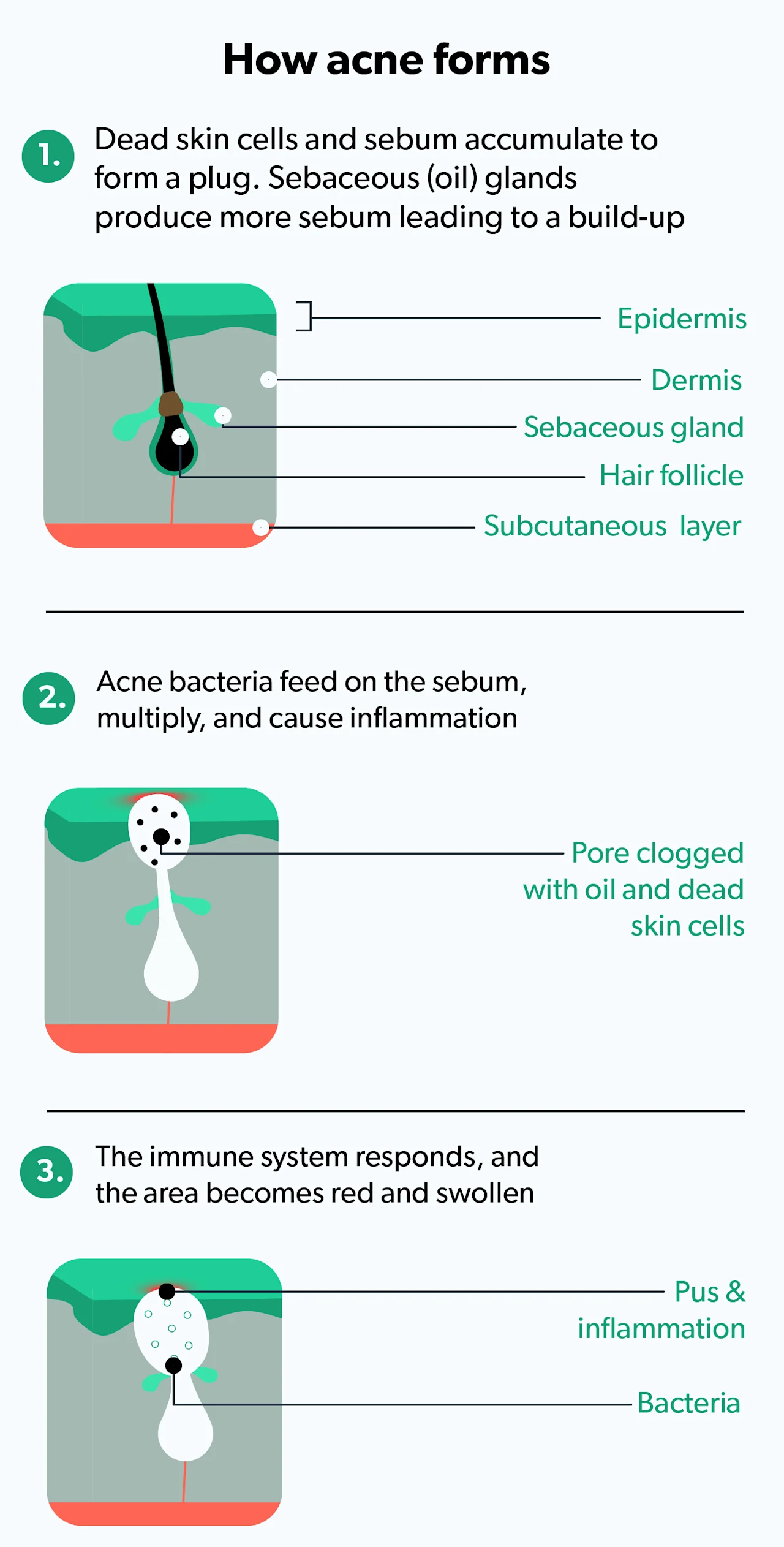

Acne is a skin condition in which a skin pore or hair follicle becomes clogged with oil (sebum) and dead skin cells. This causes redness and irritation in the skin in the form of a whitehead or a blackhead. In some cases, the clogged pore then also gets infected with a skin bacteria known as Propinum acnes (P. acnes), causing even more inflammation (Sutaria, 2021).

Women in the U.S. tend to be more prone to adult acne than men, with approximately 12–22% of women getting adult acne, whereas only 4–6% of men suffer from the condition (Tanghetti, 2014). While not dangerous, acne can cause permanent scarring, self-esteem and self-image issues, depression, and anxiety.

Signs of acne

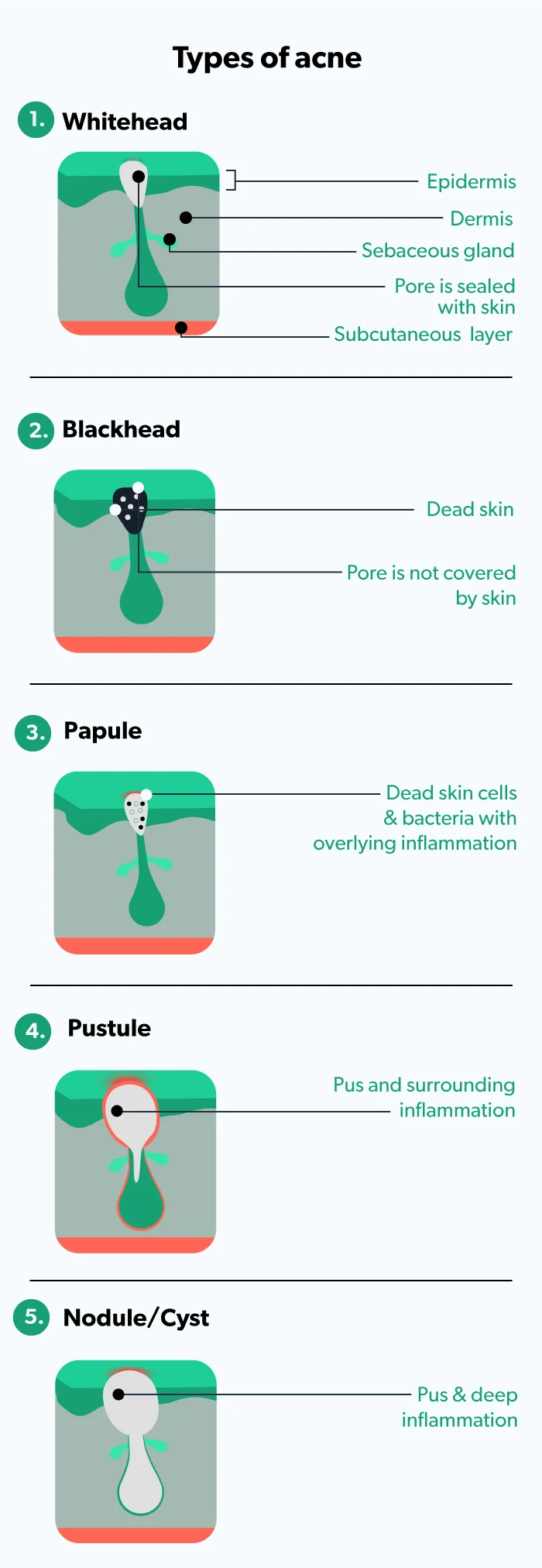

You are probably already familiar with the signs of acne. But the acne blemishes may look different from each other; you can have a bunch of one type or a mix of various ones. The common signs of the different types of acne include (Sutaria, 2021):

Whiteheads: no inflammation and pore is sealed with skin (called closed comedones)

Blackheads: no inflammation and pore is open (called open comedones)

Papules: small amounts of inflammation

Pustules: more inflammation and pus in the pore

Nodules/cysts: deep inflammation and infection

Risk factors for acne

Several factors can affect “breakouts” of acne, including hormonal imbalances, stress, diet, genetics, cosmetics, hygiene habits, medications, friction, and underlying medical conditions (Thiboutot, 2021).

Hormone imbalance

Hormones play a significant role in acne. If your hormonal balance changes, you may develop acne. When someone has an abnormal ratio of estrogens (“female hormones”) and androgens (“male hormones”), they can develop acne. Androgens increase the amount of oil produced by the skin, making you more likely to develop acne. Some people are more prone to hormonal imbalances, especially around their periods, during or after pregnancy, and around (or during) menopause (Thiboutot, 2021).

Stress

There is a definite link between stress and acne. When you are under stress, your body releases certain hormones that stimulate more oil production. This increased oil makes your existing acne more likely to worsen (Zari, 2017).

Diet

Diet may affect acne, but the myth that greasy food causes acne is not exactly true. Some studies show that following a high-glycemic-index diet may worsen acne. High-glycemic-index foods include white bread, white rice, sugary cereals, snack foods, etc. and cause your blood sugar to spike quickly after eating. The theory is that having a sugar spike causes you to secrete more oils in your skin and increases inflammation, leading to more acne (Dall'Oglio, 2021; Berbudi, 2020).

Other studies suggest that people who drink cow’s milk (but not cheese) have a higher risk of developing acne. But more research is needed in this area (Juhl, 2018).

Genetics

If your parents or siblings had acne, it is more likely that you will have it, too. Some studies suggest that there’s a more than threefold risk among people who have first-degree family members with acne (Di Landro, 2012).

Cosmetics

Certain hair products or skincare products can worsen acne, especially if they are oily or tend to clog pores. When shopping for cosmetics for your hair and skin, look for products that have the following terms on the label:

Non-comedogenic

Oil-free

Non-acnegenic

Won’t clog pores

Also, always remember to remove your make-up before going to bed.

Hygiene habits

Many people believe that acne is a result of dirty skin, but this is not true. If you over-cleanse your face, you increase your chance of having acne. Washing your face multiple times a day, face scrubbing, and vigorously rubbing your face after a workout are all habits that can irritate your skin and lead to acne forming. You should wash your face with a gentle cleanser and pat it dry. Also, avoid allowing your skin to become too dry. Using a non-comedogenic moisturizer can help keep your skin clear.

Medication side effects

Certain medications (like corticosteroids, antidepressants, anti-seizure drugs, and some types of birth control pills) can cause acne as one of their side effects. If you are taking medications that you think may be causing (or aggravating) your acne, be sure to talk to your healthcare provider (Kazandjieva, 2017).

Friction

Repeated pressure or friction on the skin, such as from a helmet, bra straps, or backpack, can lead to specific areas of acne.

Underlying medical conditions

Acne can sometimes be an indication of an underlying medical condition, like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). If this is the case, once the medical condition is diagnosed and treated, the acne often resolves (Witchel, 2019).

When to see your healthcare provider

While acne can be frustrating, especially as an adult, many treatments are available. Your acne can be treated, but it may take some time to find the therapy that works best for you. Mild acne may improve with topical treatments purchased over-the-counter. However, you should consult a dermatologist if your acne causes you embarrassment or depression, does not improve, or causes dark spots or scars.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

American Academy of Dermatology (AAD). (n.d.). Skin conditions by the numbers. Retrieved Oct 29, 2021 from https://www.aad.org/media/stats-numbers

Berbudi, A., Rahmadika, N., Tjahjadi, A. I., & Ruslami, R. (2020). Type 2 diabetes and its impact on the immune system. Current Diabetes Reviews , 16 (5), 442–449. doi: 10.2174/1573399815666191024085838. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31657690/

Castillo, D. E., & Keri, J. E. (2018). Chemical peels in the treatment of acne: patient selection and perspectives. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology, 11 , 365–372. doi:10.2147/CCID.S137788. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30038512/

Cooper, D. B. & Mahdy, H. (2021). Oral contraceptive pills. [Updated 2021 Aug 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct 29, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430882/

Dall'Oglio, F., Nasca, M. R., Fiorentini, F., & Micali, G. (2021). Diet and acne: review of the evidence from 2009 to 2020. International Journal of Dermatology , 60 (6), 672–685. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15390. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33462816/

Di Landro, A., Cazzaniga, S. (2012). Family history, body mass index, selected dietary factors, menstrual history, and risk of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and young adults. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 67(6), 1129–1135. Doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.018. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22386050/

Fallah, H., & Rademaker, M. (2021). Isotretinoin in the management of acne vulgaris: practical prescribing. International Journal of Dermatology, 60 (4), 451–460. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15089. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32860434/

Guerra, K. C., Zafar, N., & Crane, J. S. (2021). Skin cancer prevention. [Updated Aug. 14, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct. 8, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519527/

Juhl, C. R., Bergholdt, H., Miller, I. M., Jemec, G., Kanters, J. K., & Ellervik, C. (2018). Dairy intake and acne vulgaris: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 78,529 children, adolescents, and young adults. Nutrients , 10 (8), 1049. doi: 10.3390/nu10081049. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30096883/

Kazandjieva, J., & Tsankov, N. (2017). Drug-induced acne. Clinics in Dermatology , 35 (2), 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.10.007. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28274352/

Pile, H. D. & Sadiq, N. M. (2021). Isotretinoin. [Updated 2021 May 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct 29, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525949/

Sutaria, A. H., Masood, S., & Schlessinger, J. (2021). Acne vulgaris. [Updated 2021 Aug 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct 29, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459173/

Tanghetti, E. A., Kawata, A. K., Daniels, S. R., Yeomans, K., Burk, C. T., & Callender, V. D. (2014). Understanding the burden of adult female acne. The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology , 7 (2), 22–30. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24578779/

Thiboutot, D., & Zaenglein, A. (2021). Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of acne vulgaris. In UptoDate . Levy, M.L, Owen, C., and Ofori, A.O. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-acne-vulgaris

Thiboutot, D. M., Dréno, B., Abanmi, A., Alexis, A. F., Araviiskaia, E., et al. (2018). Practical management of acne for clinicians: An international consensus from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology , 78 (2 Suppl 1):S1-S23.e1. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29127053/

Witchel, S. F., Oberfield, S. E., & Peña, A. S. (2019). Polycystic ovary syndrome: pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment with emphasis on adolescent girls. Journal of the Endocrine Society , 3 (8), 1545–1573. doi: 10.1210/js.2019-00078. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31384717/

Yoham, A. L. & Casadesus, D. (2020). Tretinoin. [Updated 2020 Dec 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct 29, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557478/

Zaenglein, A., Pathy, A., Schlosser, B., Alikhan, A., Baldwin, H., & Berson, D. et al. (2016). Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology , 74 (5), 945-973.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26897386/

Zaenglein A. L. (2018). Acne vulgaris. The New England Journal of Medicine , 379 (14), 1343–1352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1702493. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30281982/

Zari, S., & Alrahmani, D. (2017). The association between stress and acne among female medical students in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology , 10, 503–506. doi:10.2147/CCID.S148499. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5722010/ .