Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

The "fountain of youth" has been the subject of stories and legends since the time of ancient civilizations. Over time, the desire to look young has not diminished—if anything, the cosmetic industry has made more people think about looking young than ever before.

Most people don’t realize that aging skin can begin as early as your 30s and 40s, and may not start taking preventative measures until it’s too late. Unfortunately, scientists have yet to discover the "cure" for aging. However, there are anti-aging options for delaying the inevitable.

What is aging skin?

Aging takes its toll on our bodies both inside and out. We’ve all felt the change of increasing aches and pains, lowered endurance, etc. Your skin is no different—it also suffers from the effects of aging, both functionally and visually. Over time, the underlying structure of our skin starts to break down. We begin to lose collagen and elastin fibers, proteins that are vital for your skin’s firmness and elasticity (Shanbhag, 2019).

Unfortunately, collagen and elastin are not the only things to go. Aging also lowers the levels of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), like hyaluronic acid. GAGs act as natural moisturizers, pulling water into cells. The loss of these molecules translates to a decrease in skin volume and firmness (Ahmed, 2020).

All of these changes (and more) result in aging skin. While there is no way to stop the aging process, there are ways to slow it down—at least with regards to how youthful your skin looks.

What are the signs of skin aging?

To some degree, skin aging can vary among individuals based on their genetics, ethnicity, how well they took care of their skin when they were younger, etc. However, some features of skin aging are relatively standard, including (Zhang, 2018):

Decreased skin elasticity: Think of a rubber band used over and over. With time, that rubber band does not snap back the way it used to and stays stretched out—this is a loss of elasticity and is similar to what happens to our skin over time. Your skin may feel loose or sag and no longer have that firm, tight look you had when you were younger.

Wrinkles and deep creases: Dynamic wrinkles are ones that you only see with facial expressions, like the fine lines around your eyes when you smile. Over time, wrinkles become permanent and are present regardless of facial movement.

Dark spots or hyperpigmentation

Coarse skin texture

Visible thin blood vessels

Thinner and more fragile skin

Loss of fat and muscle under the skin, giving a hollow look

Causes of aging skin

As we age, we experience both intrinsic and extrinsic causes of skin aging.

Intrinsic factors are beyond our control. One example is the loss of soft tissue (muscle, fat) from under the skin that usually occurs with aging. This loss leads to a "deflated" appearance (rather than a plump, youthful look) and causes the skin to sag, creating deeper and more numerous wrinkles. Loss of skin elasticity in the skin also occurs with age and contributes to skin sagging and the appearance of wrinkles (Ko, 2017).

Skin metabolism and turnover also change as we age; the skin becomes thinner and breaks down collagen instead of creating it. These changes cause the facial skin to be thin and dry with blotchy or mottled coloration (Shanbhag, 2019). Genetics certainly plays a role in aging and is another intrinsic factor to take into consideration.

Extrinsic causes of aging are ones that you can modify if you start early; it is easier to prevent extrinsic aging than it is to reverse it. The most common culprit of extrinsic aging is sun damage (also known as photoaging or premature aging).

When you expose your skin to the sun, it receives ultraviolet A (UVA) and ultraviolet B (UVB) rays—both of these types of UV rays cause damage to the skin. This sun damage causes you to look older than you naturally would. Up to 80% of aging skin changes may be due to sun damage and not just getting older (Shanbhag, 2019). Too much sun exposure (either outdoors or indoor tanning beds) not only makes you look older than your age but also increases your risk of skin cancers (Guerra, 2021).

Cigarette smoking is another common cause of extrinsic aging, regardless of sun damage or other factors. The chemicals in cigarette smoke can speed up the aging process by causing oxidative stress that damages skin cells and blood vessels. It also makes your skin rougher, increases the risk of wrinkles, and changes skin pigmentation and radiance (Krutmann, 2017).

Treatments for aging skin

Nothing will permanently erase facial lines and remove wrinkles or definitively prevent new ones from showing up. But several treatments can help you have smoother skin and help delay the signs of aging. People and skin types respond differently, so results may vary. Most treatments are only effective for as long as you are using them.

Retinoids

Tretinoin (brand name Retin-A) is a topical prescription medication effective at improving the appearance of aging skin. It belongs to the retinoid drug class, derived from vitamin A (also called retinol). Tretinoin can improve the fine wrinkles, skin looseness, and brown spots seen in aging skin. Other prescription retinoids include tazarotene and adapalene. You often find retinol and its derivatives in anti-aging serums and creams.

These products work by increasing skin cell turnover, or how quickly your body sheds old, dead skin cells to allow new skin growth. But that’s not all—they also boost your skin cells' ability to replenish collagen, keeping your skin plump and smooth (Yoham, 2020).

While they may sound like the miracle cure for aging, there are downsides. Retinoids are not a quick fix—it can take several months for improvements in aging skin to show. They can also make your skin more sensitive to the sun and more likely to burn. Lastly, a common side effect of tretinoin is dryness and irritation, especially when you start treatment. It’s a must to use sunscreen and moisturizers while using retinoids.

Tretinoin Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

Over-the-counter treatments

Other treatments may also help improve the appearance of aging skin, but the scientific data on how these compounds affect aging skin is limited (Draelos, 2018; Ahmed, 2020):

Antioxidants (e.g., niacinamide, omega-3-fatty acids)

Vitamins (e.g., vitamin C and vitamin E)

Hydroxy acids (e.g., alpha-hydroxy acids and beta-hydroxy acids)

Procedures to help aging skin

If you need more anti-aging help, talk to your dermatologist about cosmetic procedures that can more aggressively address aging skin issues at the cellular level. These procedures range from quick in-office treatments to more invasive surgery. Examples include:

Botulinum toxin (brand name Botox) weakens specific facial muscles (usually the forehead and around the eyes and mouth) to decrease the appearance of dynamic wrinkles (wrinkles that come from repeated facial movement) (Satriyasa, 2019).

Injectable fillers (e.g., Juvederm, Restylane, Radiesse) and volumizers fill deep wrinkles and give your face a fuller look (Walker, 2021).

Laser treatments may be an option to improve the signs of premature aging, depending on your skin tone, amount of sun damage, and other factors. There are different lasers (ablative, non-ablative, etc.), each with varying degrees of effectiveness, required downtime, and associated risks. These lasers create controlled stress that triggers a wound healing response, prompting the body to resurface the damaged area (Verma, 2021).

Chemical peels use harsh chemicals to remove the outer layer of the skin, promoting skin regrowth to even out skin tone and tighten loose skin (Pathak, 2020).

Cosmetic surgery is the most effective at improving wrinkles and skin laxity, especially in older people, but has the highest potential risks and most prolonged downtime (McCullough, 2006).

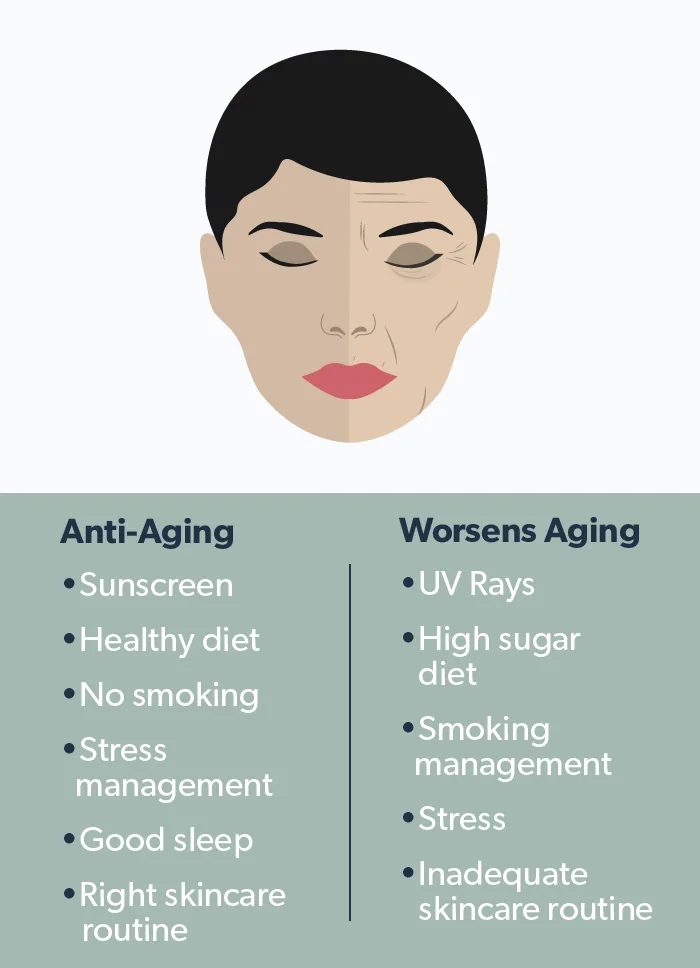

How to slow the signs of aging

As technology advances, scientists are learning more about the process of aging and how to slow it down—but a great deal is still not understood. The best things you can do to keep your skin looking young are quitting smoking and preventing sun damage by using sun protection. You should apply sunscreen whenever you are going outside, even if it is a cloudy day. Be sure to use a broad-spectrum (protects against UVA & UVB) sunscreen with a rating of at least 30 SPF. Wearing protective clothing, like a wide-brimmed hat and sunglasses, can also protect you against premature aging.

Lastly, any kind of tanning is unhealthy for your skin. Contrary to popular belief, getting a tan does not protect you from sunburns or sun damage. Regardless of your age, you should protect your skin from further damage with the appropriate skincare and sun protection.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Ahmed, I. A., Mikail, M. A., Zamakshshari, N., & Abdullah, A.-S. H. (2020). Natural anti-aging skincare: role and potential. Biogerontology , 21 (3), 293–310. doi: 10.1007/s10522-020-09865-z. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32162126/

Draelos Z. D. (2019). Cosmeceuticals: what's real, what's not. Dermatologic Clinics , 37 (1), 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.07.00. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30466682/

Guerra, K. C., Zafar, N., & Crane JS. (2021). Skin cancer prevention. [Updated Aug 14, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct 21, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519527/

Ko, A., Korn, B., & Kikkawa, D. (2017). The aging face. Survey Of Ophthalmology , 62 (2), 190-202. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.09.002. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27693312/

Krutmann, J., Bouloc, A., Sore, G., Bernard, B. A., & Passeron, T. (2017). The skin aging exposome. Journal of Dermatological Science , 85 (3), 152–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2016.09.015. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27720464/

McCullough, J. (2006). Prevention and Treatment of Skin Aging. Annals Of The New York Academy Of Sciences , 1067 (1), 323-331. doi: 10.1196/annals.1354.044. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16804006/

Pathak, A., Mohan, R., & Rohrich, R. J. (2020). Chemical peels: role of chemical peels in facial rejuvenation today. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery , 145 (1), 58e–66e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006346. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31881607/

Satriyasa, B. K. (2019). Botulinum toxin (Botox) A for reducing the appearance of facial wrinkles: A literature review of clinical use and pharmacological aspect. Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology , 12 , 223-228. doi: 10.2147/ccid.s202919. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6489637/

Shanbhag, S., Nayak, A., Narayan, R., & Nayak, U. Y. (2019). Anti-aging and sunscreens: paradigm shift in cosmetics. Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin , 9 (3), 348–359. doi: 10.15171/apb.2019.042. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6773941/

Verma, N., Yumeen, S., & Raggio, B. S. (2021). Ablative laser resurfacing. [Updated Aug 13, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct. 21, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557474/

Walker, K., Basehore, B. M., Goyal, A., et al. (2021). Hyaluronic acid. [Updated July 7, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct 21, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482440/

Yoham, A. L. & Casadesus, D. (2020) Tretinoin. [Updated Dec 5, 2020]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Oct 21, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557478/

Zhang, S., & Duan, E. (2018). Fighting against skin aging: the way from bench to bedside. Cell Transplantation , 27 (5), 729–738. doi: 10.1177/0963689717725755. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6047276/