Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

No one wants to deal with an infection, but an infection on your penis? That’s probably the last thing you want to be dealing with. Pain and discomfort are not words anyone wants to associate with the most sensitive parts of their body.

The good news is balanitis is generally relatively simple to treat. And, it’s pretty common, so don’t worry, your healthcare provider has probably seen this before.

What is balanitis?

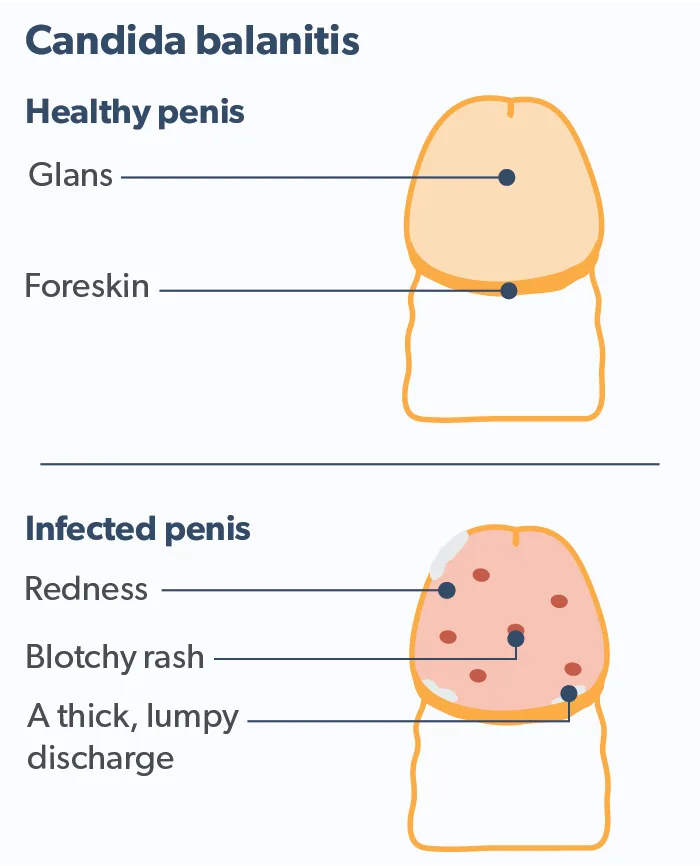

Balanitis is a painful inflammation of the head of the penis, also known as the glans. Balanitis may present in many different ways. Symptoms of balanitis include swelling, itching, burning, and red patches. One may also develop pustules (small bumps), pus-filled sacs, and small lesions. Sometimes a moist substance collects with the appearance of small, white curds. Often, symptoms will be worse in men with diabetes or who are immunocompromised (Morris, 2017).

Balanitis is closely related to two other conditions, balanoposthitis and phimosis.

While balanitis is inflammation of the glans, balanoposthitis is an inflammation of both the glans penis and the prepuce (foreskin). Some healthcare providers may even use the terms balanitis and balanoposthitis interchangeably (Wray, 2021).

Phimosis is an overly tight foreskin that won’t retract. Phimosis can be a cause or a symptom of balanitis. The two conditions may feed into the other in an ongoing feedback loop of penile pain. Recurrent balanitis can leave scarring on the prepuce, leading to phimosis (McGregor, 2007). This tight foreskin can be difficult to clean under, creating an environment for bacteria happily trapped underneath to continue the cycle of inflammation.

One dangerous type of phimosis is a condition called paraphimosis, in which a tight foreskin becomes trapped behind the head of the penis. Paraphimosis can happen if one forcibly retracts a tight foreskin. After doing this, the foreskin can’t return to its proper place over the glans. Paraphimosis is a urological emergency. Left untreated, it can “strangle” the glans and lead to tissue death (necrosis) (Bragg, 2021).

Causes of balanitis

The most common cause of balanitis is a bacterial infection brought about by poor hygiene. It is seen most often in uncircumcised men. Fungi (yeast) such as Candida albicans thrive in warm moist areas such as that under the foreskin. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including gonorrhea, chlamydia, herpes, and syphilis, may also cause balanitis. Balanitis is not itself an STI or STD. Still, one may sexually transmit the bacteria or virus responsible to a partner (Wray, 2021).

Balanitis may stem from several other medical conditions as well. These include allergic reactions, either to medications or skin contact irritants such as soaps, spermicides, or latex condoms. Some heart, liver, or kidney conditions can cause edema (swelling) in various parts of the body, including inflammation of the glans. It may also manifest from a skin condition such as psoriasis, eczema, or dermatitis (Wray, 2021).

Certain types of balanitis have specific manifestations. These include:

Zoon balanitis

Also called Zoon’s balanitis and plasma cell balanitis, this condition is a chronic inflammation of mucous membranes in the genitals. It typically affects uncircumcised middle-aged and older men. It usually presents with a shiny red, raised area (plaque), sometimes speckled with small, lighter red dots. Most instances do not cause pain or discomfort, only cosmetic changes. The cause is unknown. Some researchers believe it’s caused by a dysfunctional foreskin retaining urine and smegma (Dayal, 2016).

Balanitis xerotica obliterans

Balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), also known as penile lichen sclerosus, is a form of balanitis that can have severe symptoms. In extreme cases, these symptoms include narrowing the urethra or meatus (the opening at the end of the penis). Urination can be difficult and painful. This type of balanitis primarily affects boys aged 6–9 (Carocci, 2021).

Circinate balanitis

Circinate balanitis can be a sign of reactive arthritis, a condition often caused by a Chlamydia infection. It appears as lesions with round, ring-like, or spiral shapes on the glans or under the foreskin. Reactive arthritis usually has three significant symptoms: arthritis in the joints, conjunctivitis (pink eye), and urethritis, an inflamed urethra leading to painful urination. Other non-venereal infections such as Salmonella, Yersinia, and Shigella may cause this condition as well (Carney, 2015).

Pseudoepitheliomatous, keratotic, and micaceous balanitis

Simply referred to as PEKMB, pseudoepitheliomatous, keratotic, and micaceous balanitis is a rare form that presents as scaly, crusty skin on the glans. PEKMB is very serious, as it can be a precursor to skin cancer (Subhadarshani, 2019).

Treatment and prevention of balanitis

Treatment for balanitis will depend on the specific cause if one is determined. Poor hygiene is the leading cause of balanitis. Naturally, good hygiene is the first step to preventing most cases. If a reaction to an irritant is the culprit forcaused your balanitis, using a gentle, unscented liquid soap to clean your penis may help. Rinse thoroughly with warm water to remove all soap residue.

The most commonly identified infectious cause is a fungal or yeast infection. For these patients, a topical antifungal cream containing clotrimazole or miconazole is the standard first-line therapy. Such treatments are inexpensive and available over-the-counter. In extreme cases, an oral antifungal or topical corticosteroid may be added (Wray, 2021).

Your healthcare provider may wish to do additional tests, including blood tests or a biopsy, to check for STIs or other conditions. If such a cause is found, treating the underlying condition will usually relieve the balanitis.

Being uncircumcised carries the highest risk factor. Circumcised men are 68% less likely to develop balanitis than uncircumcised males. For recurring balanitis in uncircumcised patients, medical experts recommend circumcision (Wray, 2021).

Men with type 2 diabetes mellitus are over twice as likely to have balanitis at least once in their lives (Unnikrishnan, 2018). The relationship is so strong that chronic or recurring balanitis may be an early sign of pre-diabetes. Patients with multiple bouts may wish to have their blood glucose levels checked (Wray, 2021).

Other conditions that increase balanitis risk include morbid obesity, external catheter use, and living in a nursing home environment (Wray, 2021).

The bottom line

If you have swelling, itching, or any apparent skin disorder on your penis, don’t simply try to treat it yourself. Although some over-the-counter medications may relieve the symptoms, they could be a warning sign of a more serious condition. Talk to your healthcare provider or a specialist such as a dermatologist, and follow their medical advice.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Bragg, B. N., Kong, E. L., & Leslie, S. W. (2021). Paraphimosis. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29083645/

Carney, R., Buhary, T., Teh, L.-S., & Gayed, S. (2015). Circinate balanitis as the presenting symptom of sexually-acquired reactive arthritis: A case report. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 65 (634), 266–267. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X685057. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25918330/

Carocci, K., & McIntosh, G. V. (2021). Balanitis xerotica obliterans. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33620847/

Dayal, S., & Sahu, P. (2016). Zoon balanitis: A comprehensive review. Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS, 37 (2), 129–138. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.192128. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27890945/

McGregor, T. B., Pike, J. G., & Leonard, M. P. (2007). Pathologic and physiologic phimosis: Approach to the phimotic foreskin. Canadian Family Physician Medecin De Famille Canadien, 53 (3), 445–448. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17872680/

Morris, B. J., & Krieger, J. N. (2017). Penile inflammatory skin disorders and the preventive role of circumcision. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 8 , 32. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_377_16. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28567234/

Subhadarshani, S., Gupta, V., Sarangi, J., Agarwal, S., & Verma, K. K. (2020). Pseudoepitheliomatous, keratotic, and micaceous balanitis. Dermatology Practical & Conceptual, 10 (1), e2020012. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1001a12. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31921499/

Unnikrishnan, A. G., Kalra, S., Purandare, V., & Vasnawala, H. (2018). Genital infections with sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: Occurrence and management in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 22 (6), 837–842. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_159_17. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30766827/

Wray, A. A., Velasquez, J., & Khetarpal, S. (2021). Balanitis. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30725828/