Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If your baby’s healthcare provider has told you that your baby has cryptorchidism—also known as undescended testicle—know that this is common. About 3% of full-term and 30% of premature male infants are born with an undescended testicle each year (Leslie, 2021).

Undescended testicles often descend on their own by the age of three months or undergo corrective surgery by the time the child is one year old. Even with timely treatment, those who had an undescended testicle are at increased risk for some health conditions, so it is beneficial to know why cryptorchidism occurs and what to watch for (Leslie, 2021).

What is cryptorchidism?

Cryptorchidism occurs when a testicle (one or both) hasn’t moved into the scrotum—the sack of skin below the penis that holds testicles—by the time a baby is born. Usually, just one testicle fails to drop down (unilateral cryptorchidism), but about 10% of the time both testes remain undescended at birth (bilateral cryptorchidism). For most, the testicle moves into the correct position by three months of life. However, about 1% of boys will need surgery to correct the condition (Leslie, 2021).

What causes an undescended testicle?

Being born prematurely poses a higher risk for cryptorchidism. In babies who are delivered after a regular nine-month pregnancy and are not underweight, the causes are harder to pinpoint. A combination of genetics, maternal health, and the fetal environment are believed to affect hormones and testicular development. The following risk factors have the strongest evidence linking them to increased risk for cryptorchidism (Leslie, 2021; Gurney, 2018):

Premature birth (testicles don’t have time to descend)

Low birth weight

Family history of cryptorchidism or other problems with genital development

Conditions that can affect development, such as Down’s Syndrome

Gestational diabetes

Preeclampsia

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy

Beyond these well-known risk factors, there are a variety of suspected risks posed to a baby during pregnancy. Heavy alcohol use has been linked to cryptorchidism. Research also shows that some pesticides may be interfering with testicle development and the descent of testicles (Gurney, 2018).

Diagnosing cryptorchidism

During gestation, testicles form in the abdomen of a male infant. These drop down into the scrotum by birth. If they don’t, there will be a flat section of the scrotal sac where a testicle or testes should be (Shin, 2020).

At a baby’s first physical examination, a diagnosis is usually pretty simple. A pediatric urologist may be able to feel undescended testes. Often a testicle gets stuck in the inguinal canal—a tube that allows for testicular descent. There are two of these tubes, one for each testicle. If a testicle is not palpable or easily felt, it may be higher up in the intra-abdominal area. A pelvic ultrasound, a simple procedure, can help find it (Leslie, 2021; Hadziselimovic, 2017).

Conditions that can look similar to an undescended testicle are retractile and ascending testicles (Shin, 2020).

Retractile and ascending testicles

Sometimes a testicle that is there at birth disappears. If that happens, there’s a good chance the child has a retractile testicle. This is not considered abnormal and can usually be moved into place. Though they may go up and down, a retractile testicle usually drops down and stays before puberty. In some, a testicle there at birth will go back into the groin and stay there. This is called an ascending testicle and will require surgery (Hutson, 2018).

Treating cryptorchidism

Treatment of cryptorchidism involves a surgery called orchiopexy or orchidopexy. It involves bringing down the undescended testicle(s). A technique called laparoscopy, which uses a tiny camera as a guide, is often used and requires just a small incision. Studies show laparoscopic surgery is a better option when trying to bring down intra-abdominal testes. Healthcare providers can also use it to search for missing testes (Abbas, 2012).

The American Urological Association (AUA) suggests that medical providers perform orchiopexy on babies from 6–18 months, though many experts recommend performing it at six months of age to protect fertility. The longer the testicle or testicles remain in the body, the greater the loss of fertility (Leslie 2021).

Surgery has the added benefit of preventing testicular torsion—the twisting of the spermatic cord—which can cut off blood flow to the testicle and lead to the loss of a testicle. Testicular torsion is more likely to happen if a testicle is in the groin (Naour, 2017).

Complications of cryptorchidism

For the testicles to develop normally, they need to be outside the body where it’s cooler. Having an undescended testicle remain in the body for even just a few months as a baby increases the risk of both infertility and testicular cancer (Niedzielski, 2016).

Reduced fertility

Having surgery as a baby does improve fertility later in life. For those with two untreated undescended testicles, the risk of infertility is about 89%. That number drops to 35% in men that received treatment as babies. For those who had surgery to correct one undescended testicle, the infertility rate is only about 10%.

Surgery can improve sperm count even when treatment takes place after the second year of life. Still, the earlier treatment occurs, the better for fertility, and many men with cryptorchidism go on to have biological children. (Niedzielski, 2016; Fawzy, 2015).

Increased risk for testicular cancer

Having an undescended testicle is one of the few known risk factors for testicular cancer (Gurney, 2017). Studies show that if someone treats cryptorchidism before puberty, the incidence of testicular tumors is about three times that of the general population. However, if someone waits to treat it after puberty, the risk is higher. For those who treat it before puberty, age seems to have little impact with the risk of cancer remaining the same regardless of when treatment occurs—early in infancy or later in childhood (Braga, 2017).

The type of tumor that healthcare providers most often diagnose in untreated undescended testicles is called a seminoma. It is highly treatable if caught early. Researchers say boys who receive treatment for cryptorchidism should learn testicular self-exam to detect any tumors early (Cedeno, 2021; Leslie, 2021).

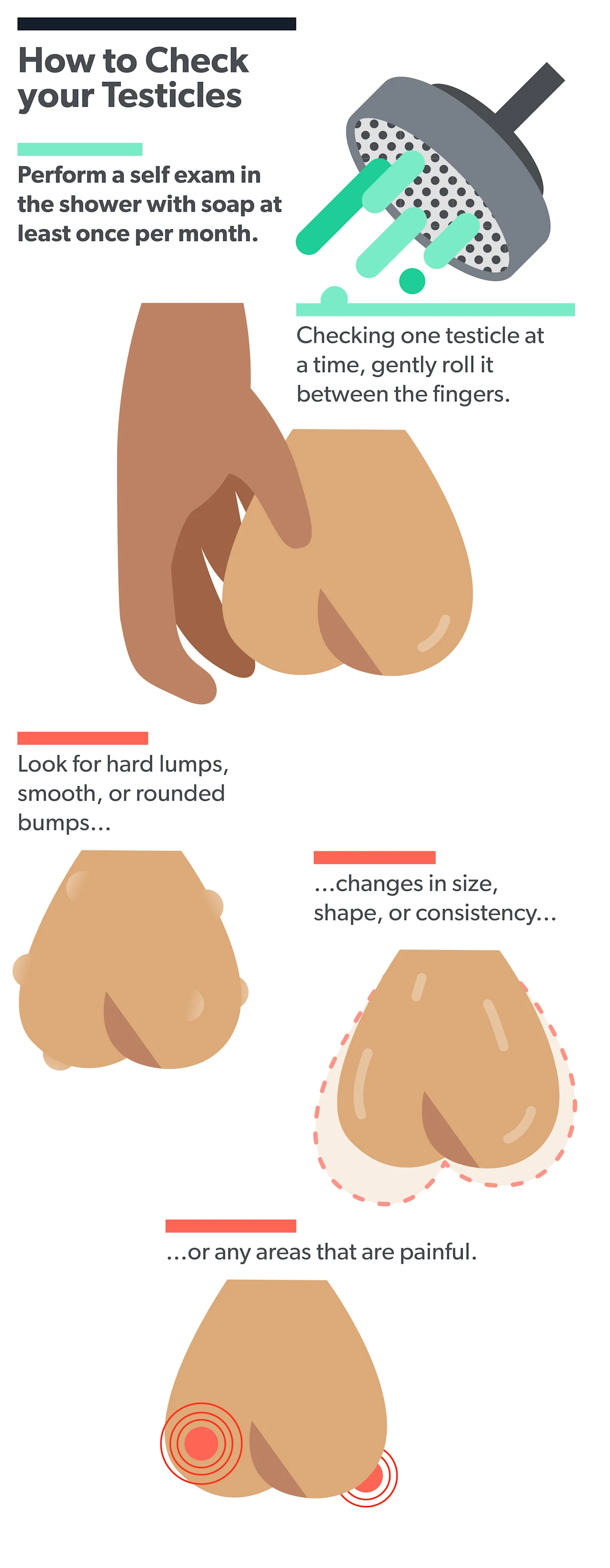

A testicular self-exam has three basic steps (ACS, 2018):

Examine each testicle separately.

Hold the testicle between your thumbs and fingers with both hands and roll it gently between your fingers.

Look and feel for hard lumps or nodules.

What to ask your healthcare provider

If you have a family risk of testicular cancer or were born with an undescended testicle, you may want to talk to your healthcare provider about the best approach to spotting tumors early (NIH, 2021).

And if you are someone who was born with cryptorchidism or are currently the parent of someone with an undescended testicle, your healthcare provider can point you toward the resources needed to support fertility and to answer any questions you may have regarding this relatively common condition.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Abbas, T. O., Hayati, A., Ismail, A., & Ali, M. (2012). Laparoscopic management of intra-abdominal testis: 5-year single-centre experience—a retrospective descriptive study. Minimally Invasive Surgery , 2012 , 1–4. doi: 10.1155/2012/878509. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22474586/

American Cancer Society. (2018). Testicular cancer screening: Finding testicular cancer. Retrieved October 12, 2021 from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/detection.html

Braga, L. H., Lorenzo, A. J., & Romao, R. L. (2017). Canadian Urological Association-Pediatric Urologists of Canada (CUA-PUC) guideline for the diagnosis, management, and followup of cryptorchidism. Canadian Urological Association Journal , 11 (7). doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4585. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5519382/

Leslie, S., Sajjad, H., & Villanueva, C. A. (2021). Cryptorchidism. [Updated Aug 12, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470270/

Cedeno, J. D. (2021). Testicular seminoma. [Updated Aug 12, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448137/

Fawzy, F., Hussein, A., Eid, M. M., Kashash, A. M., & Salem, H. K. (2015). Cryptorchidism and fertility. Clinical Medicine Insights: Reproductive Health , 9 . doi: 10.4137/cmrh.s25056. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4689328/

Gurney, J. K., McGlynn, K. A., Stanley, J., Merriman, T., Signal, V., Shaw, C., Edwards, R., Richiardi, L., Hutson, J., & Sarfati, D. (2017). Risk factors for cryptorchidism. Nature Reviews Urology , 14 (9), 534–548. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.90. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5815831/

Hadziselimovic, F. (2017). On the descent of the epididymo-testicular unit, cryptorchidism, and prevention of infertility. Basic and Clinical Andrology , 27 (1). doi: 10.1186/s12610-017-0065-8. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5686796

Hutson, J. M. (2018, July 10). Cryptorchidism and hypospadias. Endotext [Internet] . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279106/

National Cancer Institute. (2021). Testicular cancer screening (PDQ®)–patient version . Retrieved October 12, 2021 from https://www.cancer.gov/types/testicular/patient/testicular-screening-pdq

Naouar, S., Braiek, S., & El Kamel, R. (2017). Testicular torsion in undescended testis: A persistent challenge. Asian Journal of Urology , 4 (2), 111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajur.2016.05.007. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5717970/

Niedzielski, J. K., Oszukowska, E., & Słowikowska-Hilczer, J. (2016). Undescended testis – current trends and guidelines: A review of the literature. Archives of Medical Science , 3 , 667–677. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.59940. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4889701/

Rovito, M. J., Leone, J. E., & Cavayero, C. T. (2015). “off-label” usage of testicular self-examination (TSE): Benefits beyond cancer detection. American Journal of Men's Health , 12 (3), 505–513. doi: 10.1177/1557988315584942. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5987946/

Shin, J., & Jeon, G. W. (2020). Comparison of diagnostic and treatment guidelines for undescended testis. Clinical and Experimental Pediatrics , 63 (11), 415–421. doi: 10.3345/cep.2019.01438. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7642136/

Wei, Y., Wang, Y., Tang, X., Liu, B., Shen, L., Long, C., Lin, T., He, D., Wu, S., & Wei, G. (2018). Efficacy and safety of human chorionic gonadotropin for treatment of cryptorchidism: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health , 54 (8), 900–906. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13920. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29655188/