Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

What is hypospadias?

Hypospadias is a congenital condition, typically comprising one or more of three abnormalities in the penis. First, the urethral opening does not appear in the correct place at the tip of the penis. This opening, known medically as the meatus, can occur anywhere from the base of the glans (head) to as far down as the perineum (van der Horst, 2017).

The second abnormality is a ventral (downward) curvature of the head of the penis called a chordee. The third is an abnormal foreskin, with a lack of coverage on the underside and excess along the top, giving the glans a “hooded” appearance. These latter two conditions may not always be noticeable or even present (van der Horst, 2017). When these latter conditions occur without a displaced meatus, it’s sometimes called hypospadias sine hypospadias, which confusingly translates to “hypospadias without hypospadias.”

Hypospadias is the second most common congenital condition in men after cryptorchidism (undescended testicles). Hypospadias typically occurs by itself. However, studies have found that 8 to 10% of boys born with hypospadias will also have at least one undescended testicle. For those with proximal hypospadias, that number may be as high as 32% (Kraft, 2011).

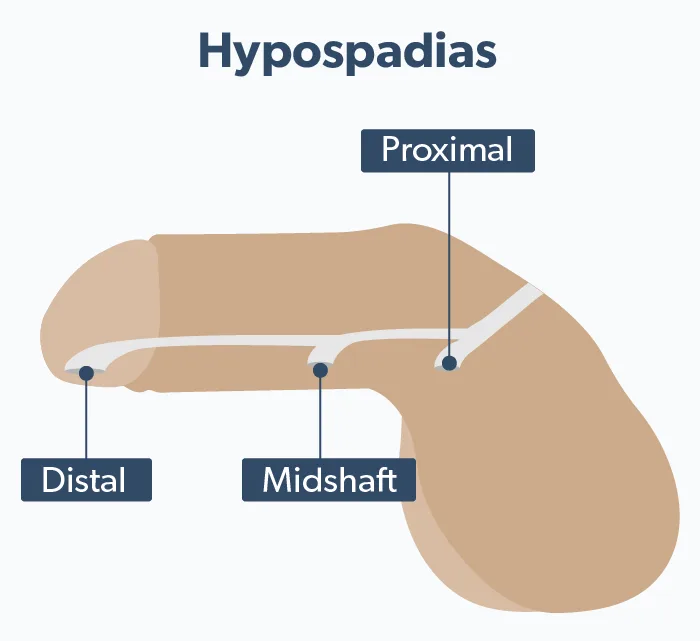

Hypospadias falls into three categories (Donaire, 2020).

Distal hypospadias is when the meatus occurs on the glans or corona, just below where it usually would. These comprise more than half of all diagnosed cases.

Midshaft hypospadias is when it occurs on the shaft of the penis.

Proximal hypospadias is when the opening of the urethra is on the scrotum or in the perineum (Donaire, 2020). These three types are also known as anterior, middle, and posterior.

Children with proximal hypospadias have a higher chance of having other disorders of sex development. These include intersex characteristics and may be caused by underlying chromosomal abnormalities.

Depending on the severity, hypospadias can cause urinary or sexual problems if left untreated. There may be difficulty peeing while standing up, or the urine stream may be splayed. The angle of a chordee could cause painful erections or the inability to ejaculate.

Causes of hypospadias

Hypospadias is relatively common, though data regarding just how prevalent it is can sometimes be contradictory. In general, studies suggest that it may be more common in North America than some other regions, affecting about 1 in 250 babies born with penises (Donair, 2020).

Hypospadias doesn’t have one specific cause. Both genetics and environmental factors may play a role. Studies estimate that for any hypospadias case, there’s a 7% chance of a first, second, or third-degree male relative having it as well. In many cases, though, a specific cause is not identified (van der Zanden, 2012).

Other conditions such as low birth weight have been linked to a higher risk of hypospadias. Studies have found several maternal disorders and conditions may contribute as well. These factors include (van der Zanden, 2012):

Placental insufficiency

Hypertension

Pre-eclampsia

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP)

High maternal BMI

Multiple pregnancies (twins or more)

Use of anti-epileptic drugs

Exposure to the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy is considered a risk factor, but this drug has not been prescribed to pregnant women since the early 1970s. It may have played a factor in some men with hypospadias born in 1972 or earlier. Multiple dietary and environmental chemicals have also been proposed as possible causes, but research on these has had mixed results (van der Zanden, 2012).

Diagnosing hypospadias

In most cases, hypospadias is diagnosed at birth. Sometimes it is evident from the abundance of the dorsal prepuce (upper foreskin) and lack of a ventral (underside) prepuce. In cases where the foreskin appears normal, hypospadias may not be found until circumcision. If it is found prior to or during circumcision, some healthcare providers may recommend delaying the procedure. A urologist can then examine the newborn before proceeding (Kraft, 2011).

Treatment

Hypospadias surgery may be done to improve urinary and sexual function. Improvements include (Anand, 2020):

Eliminating a splayed urinary stream

Enabling the patient to pee while standing

Alleviating sexual difficulties from curvature

Allowing semen to better enter the vagina during intercourse

Normalizing the appearance of genitalia

For mild cases where the opening occurs in the glans, surgery may not be necessary. However, sexual difficulties may not be discovered until later in life after one begins to have erections.

When found in newborns, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends hypospadias repair be undertaken, if necessary, between the ages of six and twelve months. This minimizes the chances of psychological or physical trauma (Kraft, 2011). Genital awareness does not begin until around eighteen months of age, and studies have found that teenagers who had surgery earlier than they could remember had more positive body images than those who had surgery later (Anand, 2020).

There may be multiple steps to the surgical repair of severe hypospadias. These include (Anand 2020):

Orthoplasty, the removal of chordee and straightening of the penis

Urethroplasty, the rebuilding of the urethra to a correct opening

Glansplasty, to correct the shape of the head of the penis.

Regular follow-up is necessary after surgery, both in the short and long term. Post-surgical complications may include (Keays, 2017):

Meatal narrowing

Urethral narrowing

Splitting open of the glans

Infections

Dribbling

Hair growth in the urethra

Skin tags, cysts, or other cosmetic issues

Erectile dysfunction

Balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), an inflammation of the glans area

Symptoms may return as well. Recurrent penile curvature has been reported following puberty. A fistula, in which the urethra opens out of the skin instead of the meatus, may develop. Outcomes for adults having hypospadias surgery are very good, though, with one study finding a 95% success rate. However, some patients, particularly those having secondary repairs, needed multiple surgeries (AlTaweel, 2017).

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

AlTaweel, W. M., & Seyam, R. M. (2017). Hypospadias repair during adulthood: Case series. Urology Annals, 9 (4), 366–371. doi: 10.4103/UA.UA_54_17. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29118541/

Anand, S., & Lotfollahzadeh, S. (2020). Hypospadias urogenital reconstruction. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33232077/

Donaire, A. E., & Mendez, M. D. (2020). Hypospadias. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29489236/

Keays, M. A., & Dave, S. (2017). Current hypospadias management: Diagnosis, surgical management, and long-term patient-centred outcomes. Canadian Urological Association Journal = Journal De l’Association Des Urologues Du Canada, 11 (1-2Suppl1), S48–S53. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4386. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28265319/

Kraft, K. H., Shukla, A. R., & Canning, D. A. (2011). Proximal hypospadias. TheScientificWorldJournal, 11, 894–906. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.76. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21516286/

van der Horst, H. J. R., & de Wall, L. L. (2017). Hypospadias, all there is to know. European Journal of Pediatrics, 176 (4), 435–441. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2864-5. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28190103/

van der Zanden, L. F. M., van Rooij, I. a. L. M., Feitz, W. F. J., Franke, B., Knoers, N. V. a. M., & Roeleveld, N. (2012). Aetiology of hypospadias: A systematic review of genes and environment. Human Reproduction Update, 18 (3), 260–283. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dms002. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22371315/