Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If you’re not ready to have children yet but may want to someday, you probably wonder about fertility preservation.

People facing medical conditions or procedures that might compromise fertility—such as cancer treatments, autoimmune diseases, and surgery—are often interested in fertility preservation, too.

Let’s look at what fertility preservation is, who it’s for, and what options are available.

What is fertility preservation?

Fertility preservation is the process of freezing a person’s eggs, sperm, reproductive tissue, or a fertilized embryo so they can have a biological child later on.

Preservation happens through a freezing and storage process called cryopreservation. Other methods you may have heard of are in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intrauterine insemination (IUI) (Peterson, 2022).

While the success of these tools depends on a number of factors (and doesn’t guarantee the birth of a healthy baby later) fertility preservation offers the chance to use frozen eggs or sperm to conceive in the future.

Reasons for fertility preservation

There are many reasons, both medical and personal, you might consider preserving your fertility. For example, if you have a medical condition or are going through cancer treatment, this gives the option of starting a family once you’re in better health.

Fertility preservation is also helpful for personal circumstances, like before a gender reassignment surgery for transgender individuals or for those who want to delay childbirth until they’ve established a career. Let’s dig further into the reasons why people consider fertility preservation.

Before cancer treatment

Cancer patients were some of the first people to be offered fertility preservation services. Not only can cancer harm reproductive health, but cancer treatments like radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and surgery can also cause fertility issues.

Pediatric cancers like Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, bone cancer, and testicular cancer all pose risks for a child’s fertility later on. Fortunately, sperm freezing (or ovarian or testicular tissue freezing, if the child is very young) preserves the option to start their own family one day and should be part of the cancer care plan discussion (Edge, 2006).

To extend the age-related fertility window

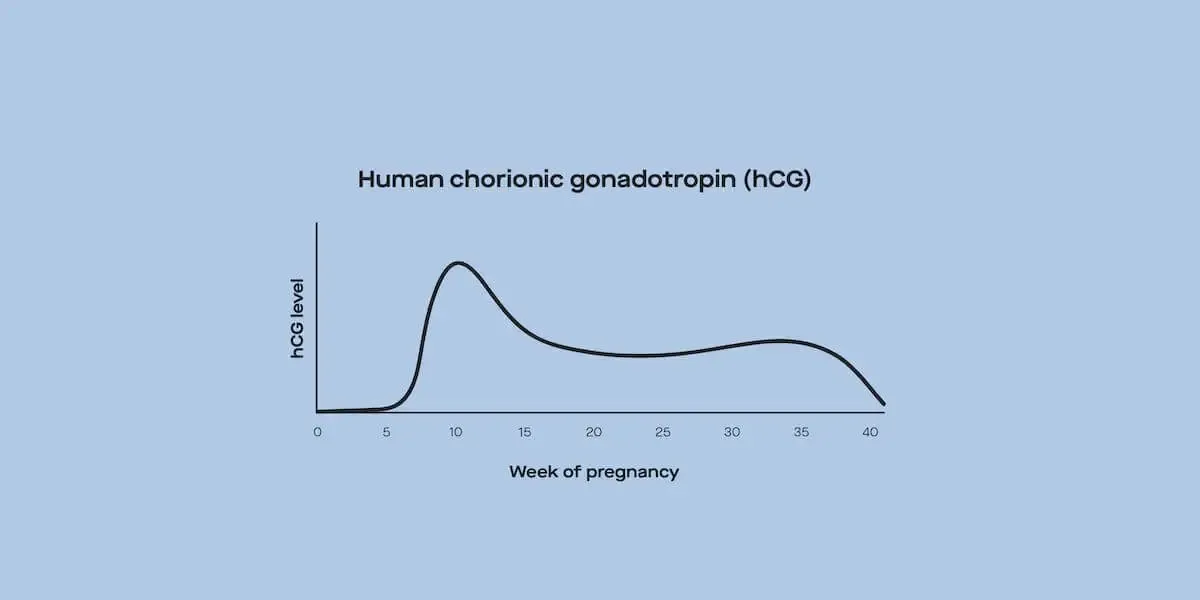

Many young people (especially women) postpone pregnancy until later in life when they’ve reached more stable personal and financial positions. While this gives more women the freedom to pursue their professional and educational goals, it may also bring concerns for future fertility (Pennings, 2021; Petropanagos, 2015).

Fertility naturally declines with age in men and women (starting over 35 for women and 40 for men). Just in case they have difficulty becoming pregnant later on, some people choose to utilize fertility preservation while they’re younger (Pennings, 2021; Petropanagos, 2015).

Freezing eggs or sperm as a non-medical fertility “backup plan” tends not to be covered by insurance. As a result, these procedures are often only available to people with higher incomes. If you’re considering fertility preservation because you’d like to have children later in life, services are sometimes available as an employer-provided benefit or through private fertility clinics.

Keep in mind that most research on the risks and side effects of egg retrieval has been done on people with fertility problems, not on young, healthy women. It’s considered safe and non-experimental, but it’s good to remember that you’ll still undergo a medical procedure (Petropanagos, 2015).

Transgender fertility preservation

Transgender individuals considering surgery or hormonal treatments to transition may want to take steps to preserve their fertility first. Important considerations are the person's age and what medical steps are aiding their transition.

For example, hormone therapy for adolescents (also called “puberty blocking”) suppresses the development of their sexual organs. This could impact their ability to produce mature sperm or eggs if they want biological children (Peterson, 2021).

If an individual is going to have gender-affirming surgery––which may involve the removal of the testicles, uterus, or ovaries––fertility preservation provides an option to have a biological child down the road.

Sperm, egg, and reproductive tissue freezing are ways transgender individuals can preserve future fertility and pursue medical steps towards transitioning. Plus, more insurance companies offer coverage for transgender care, including fertility preservation (Baker, 2017).

Underlying health conditions

Many medical issues can affect fertility. In women, this includes conditions like endometriosis, lupus nephritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. In men, infertility can be due to low sperm count and low sperm motility (Anawalt, 2022; Peterson, 2021).

Fertility preservation offers the reassurance of having another family-building tool available if conceiving a pregnancy is difficult for anyone with a health condition impacting their ability to have children.

For certain professions

People with high-risk jobs may choose to preserve their fertility in case they’re injured or have their fertility compromised by work. This applies particularly to jobs in the military, logging and agriculture industries, and other fields with high heavy metal and chemical exposure.

Fertility preservation options

Based on your age and biological sex, there are a few options for fertility preservation.

Egg freezing

Also known as oocyte cryopreservation, egg freezing is available for females and can be done for medical or personal reasons (Konc, 2014).

Egg freezing is a relatively involved process and usually includes the following steps:

Before the procedure, you’ll take medications to stimulate the ovaries to produce more eggs.

Ultrasounds or blood draws are used to monitor how the eggs are maturing over several weeks.

Once the eggs are mature, egg retrieval takes place. This is a minor surgical procedure done under general anesthesia. Egg retrieval surgery is generally safe but can cause some pain, spotting, and abdominal tenderness afterward.

The eggs are then frozen to be later fertilized with a donor or partner’s sperm. Mature eggs can also be implanted in the uterus through IVF.

Sperm freezing

Compared to retrieving eggs, sperm freezing (sperm cryopreservation) is a fairly simple process. It involves collecting a semen sample and putting it into frozen storage—typically at a sperm bank, but at-home kits are also available.

Sperm freezing involves a few steps, including:

Tests for sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

Semen collection and freezing

Frozen sperm can stay viable for an impressive amount of time—even over a decade (Huang, 2019). To fertilize an egg, the sperm is slowly thawed out and put directly into the female partner through IUI or IVF.

Embryo freezing

This method is similar to egg freezing, except that the egg is fertilized before being frozen.

Embryo freezing (or embryo cryopreservation, as you may have guessed) also involves stimulating the ovaries to produce more eggs. The fertilized embryo can later be thawed and implanted into the uterus.

Success rates of getting pregnant with IVF tend to be higher when using already-fertilized frozen embryos than ones fertilized after the fact. Still, egg freezing may be a better option for people who have ethical concerns with embryo freezing, don’t have a partner, or are still adolescents (Konc, 2014).

Reproductive tissue freezing

If a woman has a medical condition that requires immediate treatment, there may not be time for egg retrieval. In this case and for prepubescent children, reproductive tissue freezing and transplantation may be an option.

This involves removing a portion of ovarian or testicular tissue, which is where immature eggs or sperm are stored. The tissue is frozen and may later be extracted for later use in IVF. It can also potentially be transplanted back into the patient. Testicular and ovarian tissue freezing are often done for cancer patients or transgender adolescents (Peterson, 2021).

There are many reproductive technologies to help people preserve their fertility. Some reasons a person may invest in their future fertility are before a gender-affirming surgery, for age-related reasons, or before cancer treatment. If you have a medical condition that puts your fertility at risk, talk to a healthcare provider or fertility specialist about whether fertility preservation is an option for you.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Anawalt, B. (2022). Approach to the male with infertility. UpToDate . Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-male-with-infertility

Baker, K. E. (2017). The future of transgender coverage. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376 (19), 1801-1804. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1702427. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28402247/

Bayrampour, H., Heaman, M., Duncan, K. A., & Tough, S. (2012). Advanced maternal age and risk perception: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12,

doi:10.1186/1471-2393-12-100. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3490979/

Edge, B., Holmes, D., & Makin, G. (2006). Sperm banking in adolescent cancer patients. Archives of Disease in Childhood , 91 (2), 149–152. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.075242. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2082672/

Huang, C., Lei, L., Wu, H., et. al. (2019). Long-term cryostorage of semen in a human sperm bank does not affect clinical outcomes. Fertility and Sterility, 112 (4), 663-669. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.06.008. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31371041/

Konc, J., Kanyó, K., Kriston, R., et al. (2014). Cryopreservation of embryos and oocytes in human assisted reproduction. Biomed Research International . doi:10.1155/2014/307268. Retrieved from https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/307268/

Pennings, G., Couture, V., & Ombelet, W. (2021). Social sperm freezing. Human Reproduction , 36 (4), 833-839. doi:10.1093/humrep/deaa373. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/humrep/article/36/4/833/6104812?login=true

Peterson, A. M. & Singh, M. (2022). Fertility preservation in benign and malignant conditions. StatPearls . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576435/

Petropanagos, A., Cattapan, A., Baylis, F., & Leader, A. (2015). Social egg freezing: risk, benefits and other considerations. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187 (9), 666–669. doi:10.1503/cmaj.141605. Retrieved from https://www.cmaj.ca/content/187/9/666.short