Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If you and your partner have been trying to conceive for over a year, your healthcare provider may recommend certain tests, like a semen analysis, to try to get to the bottom of why you are struggling with infertility. A semen analysis looks at the overall quality of your semen, as well as the number of sperm (or “sperm count”) it contains (Leslie, 2021).

One result that you may receive following a semen analysis is “no sperm count” or azoospermia. This means that your body doesn’t make any sperm or something is blocking the sperm from reaching your ejaculate. About 10-15% of men with infertility have azoospermia (Wosnitzer, 2014).

While this may sound shocking, a diagnosis of azoospermia does not automatically mean you can’t biologically have a child. Here’s a look at what causes azoospermia and how treatment can help.

What is azoospermia?

Azoospermia means that there is no measurable sperm in a man’s ejaculate. To put some numbers behind it, a normal sperm count is 15 million sperm or more per milliliter (mL) (WHO, 2010 ). Low sperm count (oligozoospermia or oligospermia) is usually defined as a below 15 million sperm per mL. A count below 5 million per mL is considered severe oligospermia. Azoospermia is no measurable sperm count (Castaneda, 2018). There are two main types of azoospermia (Wosnitzer, 2014):

Obstructive azoospermia: a missing connection or a blockage is not allowing sperm to make it to the ejaculate even if the testicles produce healthy sperm. Approximately 40% of those with azoospermia have obstructive azoospermia.

Non-obstructive azoospermia: poor or no production of sperm is taking place. This could be due to a condition in the testicles or in the hormone balance that triggers sperm production.

What causes azoospermia?

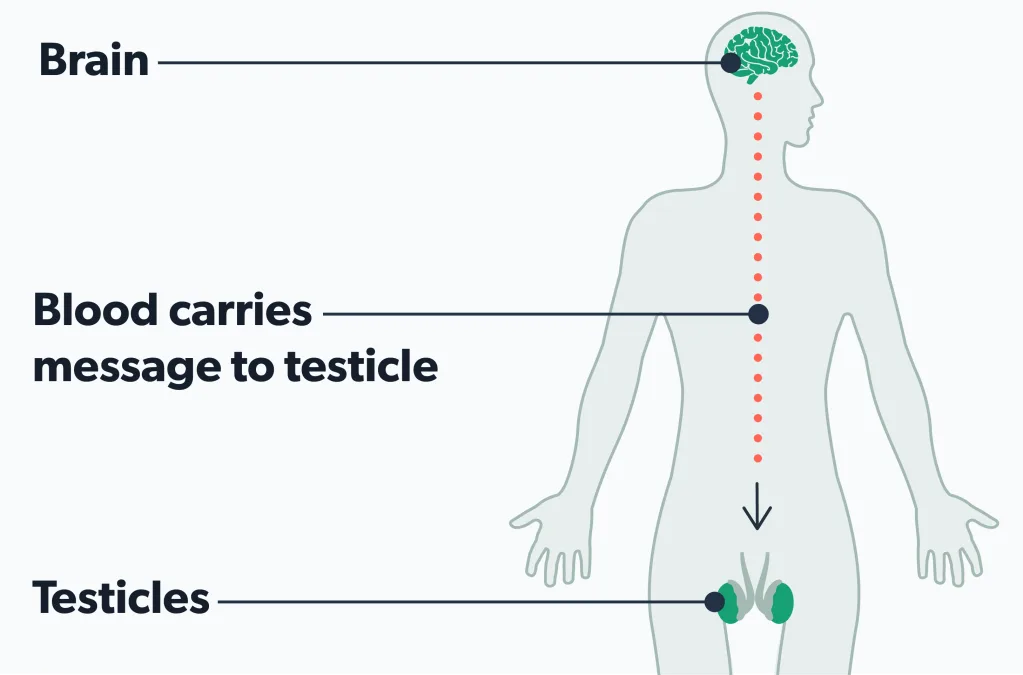

Making sperm starts with hormones that trigger tiny tubes in the testicles to produce sperm. After leaving the testicles, sperm travel through parts of the reproductive tract called the epididymis and the vas deferens. Eventually, the sperm are ready to mix with seminal fluid and leave the penis in semen during ejaculation (Suede, 2021).

In total, it takes a little over two months for sperm to grow and mature. Problems at different points during this process can lead to azoospermia. The causes of azoospermia fall into three categories (Durairajanayagam, 2015; Cocuzza, 2013):

Pre-testicular azoospermia

Pre-testicular azoospermia is a non-obstructive type (no blockage) of azoospermia caused by hormone or genetic issues (Kang 2021).

For example, Kallmann syndrome is a genetic issue that can cause this form of azoospermia. Benign brain tumors (pituitary tumors) and hormonal conditions—like hypogonadotropic hypogonadism—can also cause pre-testicular azoospermia by messing up the brain’s signaling to the testicles to make sperm (Jankowska, 2019; Tharakan, 2021).

Testicular azoospermia

Testicular azoospermia occurs when something in the testicles stops or slows the production of sperm. Some of its causes include (Tharakan, 2021; Kang 2021; Chiba, 2016):

Varicoceles (enlarged veins in the scrotum)

Testicular torsion (from a prior injury that leads to testicular damage)

Undescended testicle or missing testicles

Mumps orchitis (having mumps can cause inflamed testicles leading to blockage)

Radiation or chemotherapy

Certain medications

Sertoli cell-only syndrome (missing cells in testicles that don’t allow for sperm creation)

Spermatogenic arrest (sperm cells that don’t fully mature)

Some diseases like kidney failure, diabetes, and cirrhosis

Post-testicular azoospermia

Post-testicular azoospermia is an obstructive form of azoospermia that involves blockages that can keep sperm from making it into the ejaculate. In cases of post-testicular azoospermia, the sperm are typically healthy.

Blockages usually occur in the epididymis, vas deferens, or ejaculatory ducts. The causes of post-testicular azoospermia typically include (Jarvi, 2015):

Prior surgeries in the groin

Trauma/injury

Infections/Inflammation that blocks sperm ducts

Growth of a cyst

Gene mutation (cystic fibrosis) that leads to the absence of a vas deferens or a misformation leading to semen blockage in the vas deferens

Symptoms of azoospermia

The first sign of azoospermia is often when a couple finds they cannot conceive despite trying. But some causes of azoospermia, such as hormonal issues and blockages, may also cause other symptoms, such as (Lotti, 2016; Gudeloglu, 2013):

No or little hair on the face or body (a sign of a hormone imbalance)

Decreased libido

Swelling, discomfort, or a lump in the testicles (a sign of blockage)

Diagnosing azoospermia

Like for other male fertility issues, a semen analysis is the best test to diagnose azoospermia.

The search for sperm and a diagnosis of azoospermia requires a lab instrument called a centrifuge that can separate sperm from semen, and a high-power microscope. A diagnosis of azoospermia can be made when two semen samples on two separate occasions show no sperm in the semen (Cocuzza, 2013).

But because azoospermia can have many causes, you may need additional tests to figure out why you have no sperm in your semen. Your healthcare provider will usually ask you about your medical and family history first to identify any fertility problems linked to lifestyle, health conditions, or genetic mutations.

Illnesses like mumps, sexually transmitted infections, injuries, exposure to radiation or chemotherapy, medications, the use of alcohol and drugs, recent fevers, hot tub use, and a family history of birth defects or cystic fibrosis can affect sperm count. The talk will also involve whether you are trying to have children or have had children in the past (Cocuzza, 2013).

A physical exam may follow so your medical provider can check for signs of a varicocele (enlarged veins), a missing vas deferens, and other abnormalities in the testicles. Then, to zero in on the cause of azoospermia, your healthcare provider may order the following tests (Cocuzza, 2013):

Blood test to check hormone levels and genetic conditions

X-rays or ultrasound to check for blockages, tumors, abnormalities in the shape or size of the testicles, or to check for an inadequate blood supply in the testicles

Brain imaging to check for hypothalamus or pituitary gland conditions

Biopsy of the testicles (a normal biopsy suggests a blockage is the cause)

The reason for these additional tests (outside of hopefully helping a couple to conceive) is that men with azoospermia may be at increased risk for other health conditions. A thorough examination can help diagnose and treat these conditions (Punjani, 2021).

What are the treatments for azoospermia?

Treating azoospermia is based on its cause. Sometimes a condition can be treated, and sperm can return, allowing for normal conception. Other times, the best chance of conceiving involves extracting sperm for use in an assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedure such as in vitro fertilization (Hayon, 2020).

Ultimately, how a medical provider treats azoospermia comes down to whether it’s obstructive or non-obstructive.

Treating obstructive azoospermia

There is often plenty of healthy sperm in cases of obstructive azoospermia. The goal is to either clear the path for blocked sperm or extract sperm that is trapped but otherwise healthy. Each case is different, and your healthcare provider will determine which treatment is best, based on the type of obstruction. Usually, these are straightforward procedures that clear sperm ducts or other passageways (Jarvi, 2015). If a blockage is not simple to clear, a urologist may extract the sperm for immediate use or freeze it for future use in an ART procedure. Testicular sperm extraction (TESE) is a common approach to retrieving sperm. There may also be the option of something called microsurgical epididymal sperm extraction (MESA), which may be beneficial as sperm in the epididymis are more mature (van Wely, 2015).

Treating non-obstructive azoospermia

If a hormonal imbalance causes azoospermia, hormone therapy can stimulate the testicles to begin producing sperm to the point where natural conception can take place. In cases of a varicocele, removing the enlarged veins (varicocelectomy) may improve sperm counts.

A majority of men with non-obstructive azoospermia will not be able to boost sperm counts enough to achieve natural conception. In these cases where it’s harder to find viable sperm, a procedure called microdissection testicular sperm extraction (micro-TESE) may be the best option (Jarvi, 2015).

Sperm, once retrieved, can be frozen or used immediately in an ART procedure such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), which places the sperm directly into the egg (Zheng, 2019). However, while ICSI does have a chance of succeeding, it does not work for all men with azoospermia (Eken, 2018).

Are there natural treatments for azoospermia?

If azoospermia is caused by an obstruction, genetics, or another medical condition, there is no solid evidence that natural remedies will reverse the condition.

Some herbal supplements like maca, ashwagandha, and tribulus terrestris may help improve sperm counts or testosterone levels (Lee, 2016; Durg, 2018; Sanagoo, 2019). However, it’s best to work with a urologist to see what will work in your case.

Often, healthcare providers will suggest the following approaches because they’re good for overall health, including fertility (Skoracka, 2020):

Eat a healthy, nutrient-dense diet full of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables

Add fish to your diet 2–3 times a week

Avoid trans-fats, processed meat, and red meat

Lose weight (if needed)

Exercise regularly (Leslie, 2021)

Find ways to lower stress levels

Preventing azoospermia

Often, there is nothing a man can do to prevent azoospermia, and most cases will require medications or surgical procedures to correct it. However, there are ways to help lower the risk of azoospermia and oligospermia linked to injuries or exposures. These include (Durairajanayagam, 2018; Skoracka, 2020):

Avoiding activities that heat your testicles (hot tubs, saunas, laptops)

Avoiding activities that can lead to injuries to your testicles (Starmer, 2018)

Avoiding the use of anabolic steroids (testosterone or androgen) (El Osta, 2016)

If you’re going through medical treatments for another condition like cancer, talk to your healthcare provider about freezing your sperm if you are hoping to conceive at a later date (Kang 2021).

When to talk to an expert

If you’ve been trying to conceive for a year with no success, fertility specialists suggest couples look at fertility testing for both partners. If a man’s partner is over 35, it’s best to see a specialist after six months of trying to conceive (Leslie, 2021).

If you are planning to have children in the future and have medical issues or past exposures or injuries, and you’re concerned about fertility, it’s also good to see a specialist.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Castaneda, J. (2018). Sperm defects. Encyclopedia of Reproduction, 4, 276–281. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.64778-5. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/oligospermia

Chiba, K., Enatsu, N., & Fujisawa, M. (2016). Management of non-obstructive azoospermia. Reproductive Medicine and Biology , 15 (3), 165–173. doi: 10.1007/s12522-016-0234-z. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5715857/

Cocuzza, M., Alvarenga, C., & Pagani, R. (2013). The epidemiology and etiology of Azoospermia. Clinics , 68 (S1), 15–26. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(sup01)03. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3583160/

Durairajanayagam, D. (2015). Sperm biology from production to ejaculation. Unexplained Infertility, 29-42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2140-9_5. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283864069_Sperm_Biology_from_Production_to_Ejaculation

Durg, S., Shivaram, S. B., & Bavage, S. (2018). Withania somnifera (Indian ginseng) in male infertility: An evidence-based systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine , 50 , 247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.11.011. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30466985/

Eken, A., & Gulec, F. (2018). Microdissection testicular sperm extraction (micro-TESE): Predictive value of preoperative hormonal levels and pathology in non-obstructive azoospermia. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences , 34 (2), 103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.08.010. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29413225/

El Osta, R., Almont, T., Diligent, C., Hubert, N., Eschwège, P., & Hubert, J. (2016). Anabolic steroids abuse and male infertility. Basic and Clinical Andrology , 26 (2). doi: 10.1186/s12610-016-0029-4. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4744441/

Gudeloglu, A., & Parekattil, S. J. (2013). Update in the evaluation of the azoospermic male. Clinics , 68 (S1), 27–34. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(sup01)04. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3583174/

Hayon, S., Moustafa, S., Boylan, C., Kohn, T. P., Peavey, M., & Coward, R. M. (2021). Surgically extracted epididymal sperm from men with obstructive azoospermia results in similar in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes compared with normal ejaculated sperm. Journal of Urology , 205 (2), 561–567. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000001388. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33026908/

Jankowska, K., & Zgliczyński, W. (2019). Pituitary tumor as a cause of male infertility. Endocrine Abstracts . doi: 10.1530/endoabs.63.p315. Retrieved from https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0063/ea0063p315

Jarvi, K., Lo, K., Grober, E., Mak, V., Fischer, A., Grantmyre, J., Zini, A., Chan, P., Patry, G., Chow, V., & Domes, T. (2015). CUA guideline: The workup and management of azoospermic males. Canadian Urological Association Journal , 9 (7-8), 229. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.3209. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4537331/

Kang, C., Punjani, N., & Schlegel, P. N. (2021). Reproductive chances of men with azoospermia due to spermatogenic dysfunction. Journal of Clinical Medicine , 10 (7), 1400. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071400. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8036343/

Lee, M. S., Lee, H. W., You, S., & Ha, K.-T. (2016). The use of maca ( lepidium meyenii ) to improve semen quality: A systematic review. Maturitas , 92 , 64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.07.013. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27621241/

Leslie, S. W. (2021). Male infertility . [Updated Aug 12, 2021] In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562258/

Lotti, F., Corona, G., Castellini, G., Maseroli, E., Fino, M. G., Cozzolino, M., & Maggi, M. (2016). Semen quality impairment is associated with sexual dysfunction according to its severity. Human Reproduction , 31 (12), 2668–2680. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew246. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27733531/

Madej, D., Granda, D., Sicinska, E., & Kaluza, J. (2021). Influence of fruit and vegetable consumption on antioxidant status and semen quality: A cross-sectional study in adult men. Frontiers in Nutrition , 8 . doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.753843. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8554053/

Punjani, N., Kang, C., Lamb, D. J., & Schlegel, P. N. (2021). Current updates and future perspectives in the evaluation of Azoospermia: A systematic review. Arab Journal of Urology , 19 (3), 206–214. doi: 10.1080/2090598x.2021.1954415. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8451618/

Sanagoo, S., Sadeghzadeh Oskouei, B., Gassab Abdollahi, N., Salehi-Pourmehr, H., Hazhir, N., & Farshbaf-Khalili, A. (2019). Effect of tribulus terrestris L. on sperm parameters in men with idiopathic infertility: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine , 42 , 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2018.09.015. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30670288/

Skoracka, K., Eder, P., Łykowska-Szuber, L., Dobrowolska, A., & Krela-Kaźmierczak, I. (2020). Diet and nutritional factors in male (in)fertility—underestimated factors. Journal of Clinical Medicine , 9 (5), 1400. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051400. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7291266/

Starmer, B. Z., Baird, A., & Lucky, M. A. (2017). Considerations in fertility preservation in cases of testicular trauma. BJU International , 121 (3), 466–471. doi: 10.1111/bju.14084. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29164757/

Suede, S. H. (2021). Histology, spermatogenesis . [Updated Mar 21, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553142/

Sunder, M. (2020). Semen analysis . [Updated Nov 1, 2020]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564369/

Tharakan, T., Luo, R., Jayasena, C. N., & Minhas, S. (2021). Non-obstructive azoospermia: Current and future perspectives. Faculty Reviews , 10 . doi: 10.12703/r/10-7. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7894261/

van Wely, M., Barbey, N., Meissner, A., Repping, S., & Silber, S. J. (2015). Live birth rates after Mesa or Tese in men with obstructive azoospermia: Is there a difference? Human Reproduction , 30 (4), 761–766. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev032. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25740877/

World Health Organization (WHO). (2010). Who laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen . Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44261/9789241547789_eng.pdf;sequence=1

Wosnitzer, M., Goldstein, M., & Hardy, M. P. (2014). Review of azoospermia. Spermatogenesis , 4 (1). doi: 10.4161/spmg.28218. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4124057/

Zheng, D., Zeng, L., Yang, R., Lian, Y., Zhu, Y.-M., Liang, X., et al. (2019). Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection (ICSI) versus conventional in vitro fertilisation (IVF) in couples with non-severe male infertility (NSMI-ICSI): Protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open , 9 (9). doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030366. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6773417/