Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

If you’ve ever watched cable television, chances are you’ve seen commercials for antidepressants. You know the ones—a couple holding hands while walking on the beach, parents running around playgrounds with their children, people laughing with friends at a barbeque. Silly marketing aside, antidepressants have offered millions of people relief from debilitating depression symptoms that make it hard to enjoy the things they once did.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the most common mood condition affecting adults in the United States (Hillhouse, 2015). In 2019, 18.5% of adults surveyed had experienced depression symptoms within the prior two weeks (CDC, 2020). Fortunately, antidepressants can help treat these symptoms. Here’s what you should know about these medications and how they may be able to help you.

What are antidepressants?

Antidepressants are medications used to treat depression and other mental health disorders and chronic pain conditions.

Most antidepressants work by increasing levels of certain neurotransmitters or chemicals, in the brain. These neurotransmitters include serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Researchers believe that depression, in part, may be caused by low levels of these substances (Sahli, 2016).

Uses for antidepressants

Aside from treating symptoms of depression, antidepressants have proven useful for many other conditions. Several mental health disorders may benefit from an antidepressant, including anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder (GlaxoSmithKline-a, 2011).

Healthcare providers also use antidepressants to treat chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia and nerve pain caused by diabetes (Eli Lilly and Company, 2010). Antidepressants even work to prevent migraines, help people quit smoking, and treat insomnia (GlaxoSmithKline-b, 2016; Thour, 2020).

Types of antidepressants

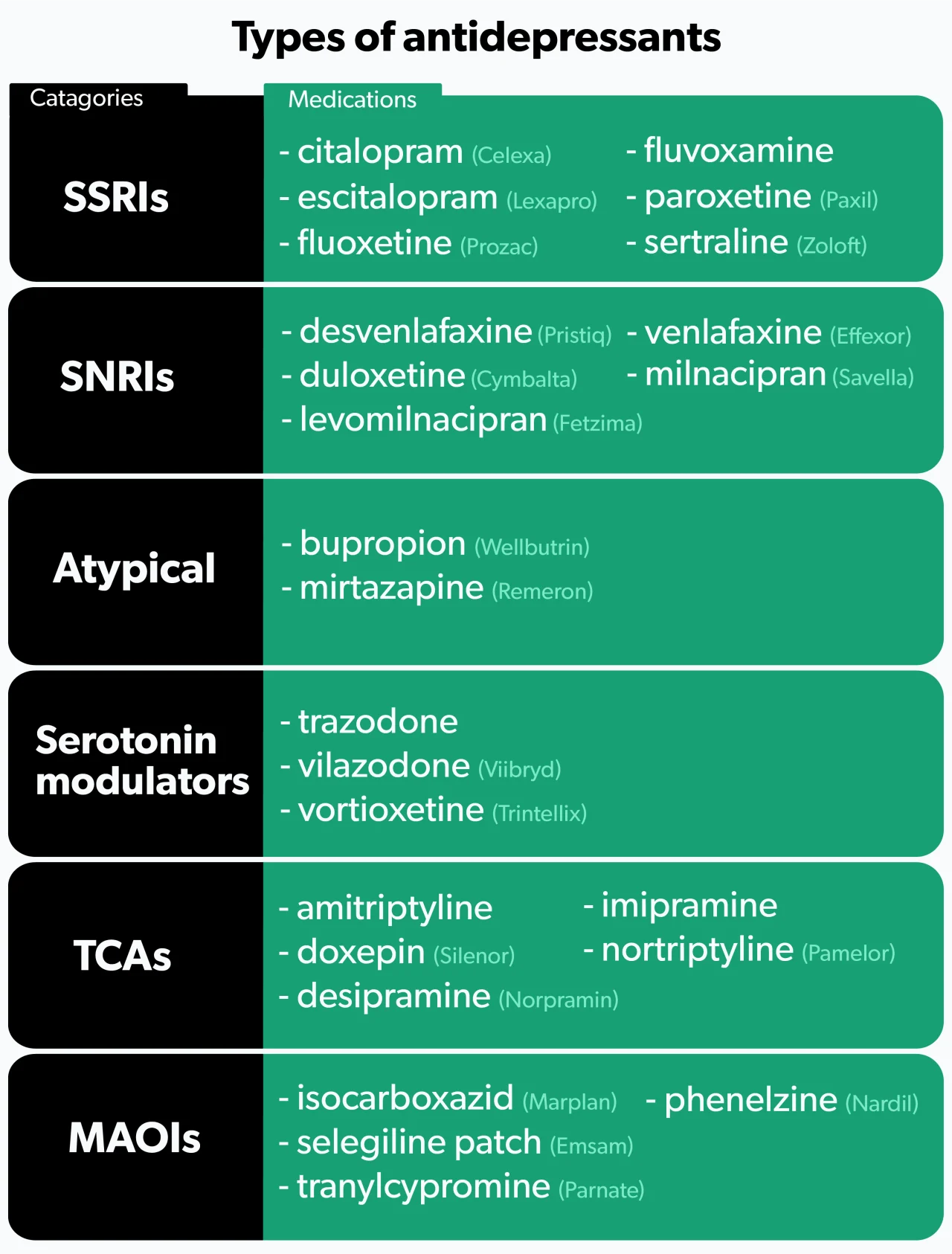

There are six main categories of antidepressants.

1. SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly prescribed antidepressants (Jha, 2016). SSRIs work by increasing the levels of serotonin in the brain (Sahli, 2016). They tend to be better tolerated than older antidepressants, but side effects do occur. People who use SSRIs may experience sexual dysfunction, tiredness, anxiety, insomnia, nausea, or weight gain (Santarsieri, 2015).

Examples of SSRIs include fluoxetine (brand name Prozac), sertraline (brand name Zoloft), and citalopram (brand name Celexa).

2. SNRIs

Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are used to treat depression, anxiety, fibromyalgia, and diabetic nerve pain (Eli Lilly and Company, 2010). As their name suggests, SNRIs increase levels of both serotonin and norepinephrine. People may experience many of the same side effects as SSRIs, but SNRIs tend to cause more nausea, insomnia, and dry mouth (Santarsieri, 2015).

Examples of SNRIs include duloxetine (brand name Cymbalta), venlafaxine (brand name Effexor), and desvenlafaxine (brand name Pristiq).

3. Atypical antidepressants

Atypical antidepressants work differently than any of the other types. These medications may be tried as initial treatment if you are looking to avoid specific side effects, or they may be given later if you have failed other therapies. Many people consider bupropion (brand name Wellbutrin) an attractive option given its low rates of sexual dysfunction and weight gain—two side effects common among many antidepressants. Some people benefit by adding bupropion to an SSRI to combat the sexual dysfunction that often occurs with SSRIs (Santarsieri, 2015).

Another atypical antidepressant, mirtazapine (brand name Remeron), causes significant weight gain and sedation. While most people wish to avoid weight gain, mirtazapine’s sedative effects can be beneficial if your depressive symptoms include difficulty sleeping (Santarsieri, 2015).

4. Serotonin modulators

Like SSRIs, serotonin modulators increase serotonin levels, but they also bind to serotonin receptors in the body. One medication in this class, trazodone (brand name Desyrel), can help if you have symptoms that include anxiety and trouble sleeping (Santarsieri, 2015).

Newer serotonin modulators—vilazodone (brand name Viibryd) and vortioxetine (brand name Trintellix)—are well-tolerated and generally cause less sexual dysfunction and weight gain compared to SSRIs. However, significant nausea can occur (Santarsieri, 2015).

5. TCAs

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are an older class of medications. Like SNRIs, TCAs increase levels of serotonin and norepinephrine. They also affect several other chemical pathways in the body, resulting in more side effects. Because of their side effect profile, TCAs are not typically the first drugs healthcare providers reach for. Common side effects include weight gain, dizziness, sedation, headache, and constipation (Thour, 2020).

TCAs can increase the risk of heart problems and should not be given to people with heart disease. Additionally, TCAs can cause seizures, so those with a history of seizures need to use them cautiously (Thour, 2020).

Examples of TCAs include amitriptyline, nortriptyline (brand name Pamelor), and desipramine (brand name Norpramin).

6. MAOIs

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) prevent the breakdown of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. They are an older class of antidepressants typically only used if you have not responded to other treatments. Their side effect profile and drug and food interactions make them less attractive options.

Patients taking MAOIs need to adhere to a strict diet, avoiding foods high in tyramine. Tyramine can interact with MAOIs and cause dangerously high blood pressure (Santarsieri, 2015). Foods high in tyramine include aged cheeses, cured meats (like bacon, sausage, and salami), and overripe fruit (Sub Laban, 2020).

There are also several drug interactions to keep in mind. MAOIs cannot be combined with other antidepressants due to the risk of serotonin syndrome—a serious condition caused by too much serotonin in the brain. Drugs used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and certain drugs of abuse like cocaine are also problematic. Many other medications can interact with MAOIs, so always talk to your healthcare provider before starting anything new, including non-prescription products (Santarsieri, 2015).

Examples of MAOIs include isocarboxazid (brand name Marplan), phenelzine (brand name Nardil), and selegiline patch (brand name Emsam), which you apply to your skin.

Antidepressant side effects

Side effects can vary depending on the antidepressant, but certain effects are more common than others. Let’s take a closer look at a few of the problems patients commonly encounter when starting treatment.

Sexual dysfunction

Almost all antidepressants can cause some degree of sexual dysfunction, particularly SSRIs and TCAs (Wang, 2018). Some reports show up to 40–65% of patients taking an SSRI will experience sexual problems. These effects can occur in both men and women and include delayed ejaculation, reduced sexual desire and satisfaction, inability to achieve orgasm, and difficulty getting and maintaining an erection (Jing, 2016).

If you’re experiencing sexual side effects, be sure to discuss your concerns with your healthcare professional. There are different ways to combat these effects, including switching to another antidepressant. Your healthcare provider may also suggest waiting to see if sexual function improves. If it doesn't improve, they may lower the dose or add a medication to combat those side effects (Jing, 2016).

Weight gain

Many antidepressant medications can cause increased appetite and weight gain, with some notable exceptions, such as bupropion (brand name Wellbutrin) and fluoxetine (brand name Prozac) (Wang, 2018). Work with your healthcare provider to develop a healthy diet and exercise regimen to help keep your weight in check. Some studies show exercise may even help with depression symptoms (Schuch, 2016)—just one more reason to get moving!

Gastrointestinal issues

People commonly report nausea, vomiting, or upset stomach, especially when starting an antidepressant or increasing the dose. Fortunately, these side effects usually go away with time, but for some, they may persist. Using an extended-release form of the medication (if available) or taking your antidepressant with food can help. Sometimes, healthcare providers will prescribe anti-nausea drugs or medicines that lower the amount of acid in the stomach if symptoms are particularly bothersome (Kelly, 2008).

Sedation and insomnia

Almost all antidepressants can either make you tired or cause anxiety and trouble sleeping (Santarsieri, 2015). Scheduling stimulating medications early in the day and sedating medications at night can help. Your healthcare provider may also recommend dividing the dose into smaller doses given throughout the day or using an extended-release product (Kelly, 2008).

Risk and warnings of antidepressants

There are a few risks and warnings to be aware of when starting an antidepressant.

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires all antidepressants to have a boxed warning—their strongest warning for serious risks—regarding the potential for increased suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Studies showed an increased risk in children and young adults but not in patients over 24. Older patients over the age of 65 show decreased suicidal thoughts and behaviors when starting an antidepressant.

The FDA points out that depression and other psychiatric conditions can cause increased suicidal behaviors on their own (without treatment). Nevertheless, the FDA urges healthcare providers and family members to monitor individuals for worsening symptoms when starting an antidepressant (Friedman, 2014).

Serotonin syndrome

Serotonin syndrome occurs when there is too much serotonin in the brain. Any drug that increases serotonin levels can cause this condition, but it most commonly occurs when two or more medications that increase serotonin are taken together. Symptoms of serotonin syndrome can be mild, causing diarrhea, nervousness, and tremor. However, the condition can progress quickly, leading to severe symptoms requiring hospitalization. Concerning symptoms include fever, confusion, and muscle stiffness. Patients may also experience sweating and agitation (Foong, 2018).

Certain antidepressants, such as MAOIs, should not be combined with other antidepressants or medications that increase serotonin. Drugs of abuse, such as MDMA (ecstasy), can also be problematic when combined with antidepressants. Many other medications can interact with your antidepressant, including over-the-counter products such as St. John’s wort, various cough and cold medicines, and diet pills. Always talk to your healthcare provider before starting anything new (Foong, 2018).

Discontinuation syndrome

You may experience withdrawal symptoms after stopping an antidepressant. Symptoms are more likely to occur if you stop taking your antidepressant abruptly or there is a large decrease in the dose. You may experience flu-like symptoms, trouble sleeping, anxiety, and tingling or burning sensations. Symptoms can occur 1–10 days after stopping your medication and typically last for 2–3 weeks (Jha, 2018).

If you’re interested in stopping your antidepressant, always consult with your healthcare provider. Together, you can determine your best course of action. If that involves stopping or switching antidepressants, your healthcare provider will likely set up a dosing plan that slowly decreases how much medication you take to help prevent withdrawal symptoms.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Pregnancy can be an exciting and hopeful time, but unfortunately, it is also a risk factor for depression. Studies estimate that 10–15% of people will develop depression during pregnancy (Carvalho, 2016).

If you are experiencing symptoms of depression, you may be wondering if it’s safe to start or continue treatment for your depression during pregnancy. While some risks to your baby may exist, most evidence suggests that the benefit of using antidepressant drugs outweighs the risks associated with leaving depression untreated (Muzik, 2106).

SSRIs are the most common antidepressants prescribed during pregnancy, although paroxetine (brand name Paxil, Brisdelle) should be avoided (Carvalho, 2016; Wichman, 2015).

If you decide to breastfeed, most antidepressants are considered safe (Carvalho, 2016). When breastfeeding, it’s always optimal to choose medications that are found in low levels in breastmilk. For antidepressants, these include sertraline (brand name Zoloft), paroxetine (brand name Paxil, Brisdelle), imipramine, and nortriptyline (brand name Pamelor) (Lanza di Scalea, 2009). Speak with your healthcare provider if you’re considering breastfeeding so they can evaluate your antidepressant regimen for safety.

Drug interactions

Many medications, even over-the-counter products, interact with antidepressants. Drugs of abuse, including MDMA (ecstasy) and cocaine, can also cause problems (Foong, 2018).

Follow these tips to help reduce your risk of drug interactions:

Always check with your healthcare provider before starting any new medications.

Keep an up-to-date list of your current medications, and share this information with all of your doctors.

If possible, fill all your prescriptions at one pharmacy; that way, the pharmacist can check for interactions.

How long do antidepressants take to work?

Antidepressants typically have a lag time before their effects start to kick in. It can take six weeks or longer to see the full benefits; although, some people begin to feel better within the first two weeks (Machado-Vieira, 2010).

Some drugs, such as anti-anxiety or pain medications, only need to be taken when you need them. Antidepressants don’t work this way. They need to be taken every day, as prescribed, to be effective.

If it’s been a couple of months and you’re still not feeling improvement, don’t worry. Only about one-third of patients respond to the first drug that’s tried (Sahli, 2016). Your healthcare provider may recommend adjusting your dose, switching or adding a medication, or participating in psychotherapy (talk therapy).

Symptoms of depression may leave you feeling discouraged and unable to concentrate on much else. If you’re struggling with depression, don’t hesitate to see your healthcare provider. Antidepressants may be one option to get you feeling better and back to doing the things you love.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Carvalho, A. F., Sharma, M. S., Brunoni, A. R., Vieta, E., & Fava, G. A. (2016). The safety, tolerability and risks associated with the use of newer generation antidepressant drugs: a critical review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85 (5), 270–288. doi: 10.1159/000447034. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27508501/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, September). Symptoms of Depression Among Adults: United States; 2019 . Retrieved May 17, 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db379.htm

Eli Lilly and Company. (2010). Cymbalta: Highlights of prescribing information . Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022516lbl.pdf

Foong, A. L., Patel, T., Kellar, J., & Grindrod, K. A. (2018). The scoop on serotonin syndrome. Canadian Pharmacists Journal : CPJ = Revue des pharmaciens du Canada : RPC, 151 (4), 233–239. doi: 10.1177/1715163518779096. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6141939/

Friedman, R. A. (2014). Antidepressants' black-box warning--10 years later. The New England Journal of Medicine, 371 (18), 1666–1668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1408480. Retrieved from https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp1408480

GlaxoSmithKline-a. (2011). Paxil (paroxetine hydrochloride) tablets and oral suspension . Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/020031s067%2C020710s031.pdf

GlaxoSmithKline-b. (2016). Zyban: Highlights of prescribing information . Retrieved from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/020711s044lbl.pdf

Hillhouse, T. M., & Porter, J. H. (2015). A brief history of the development of antidepressant drugs: from monoamines to glutamate. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 23 (1), 1–21. doi: 10.1037/a0038550. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25643025/

Jha, M. K., Rush, A. J., & Trivedi, M. H. (2018). When discontinuing SSRI antidepressants is a challenge: management tips. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175 (12), 1176–1184. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18060692. Retrieved from https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18060692

Jing, E., & Straw-Wilson, K. (2016). Sexual dysfunction in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and potential solutions: A narrative literature review. The Mental Health Clinician, 6 (4), 191–196. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.07.191. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29955469/

Kelly, K., Posternak, M., & Alpert, J. E. (2008). Toward achieving optimal response: understanding and managing antidepressant side effects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10 (4), 409–418. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/kkelly. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19170398/

Lanza di Scalea, T., & Wisner, K. L. (2009). Antidepressant medication use during breastfeeding. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 52 (3), 483–497. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b52bd6. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19661763/

Machado-Vieira, R., Baumann, J., Wheeler-Castillo, C., Latov, D., Henter, I. D., Salvadore, G., & Zarate, C. A. (2010). The timing of antidepressant effects: a comparison of diverse pharmacological and somatic treatments. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 3 (1), 19–41. doi: 10.3390/ph3010019. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27713241/

Moraczewski, J., & Aedma, K. K. (2020). Tricyclic antidepressants. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28613681/

Muzik, M., & Hamilton, S. E. (2016). Use of antidepressants during pregnancy?: What to consider when weighing treatment with antidepressants against untreated depression. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20 (11), 2268–2279. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2038-5. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27461022/

Sahli, Z. T., Banerjee, P., & Tarazi, F. I. (2016). The preclinical and clinical effects of vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery, 11 (5), 515–523. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2016.1160051. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26971593/

Santarsieri, D., & Schwartz, T. L. (2015). Antidepressant efficacy and side-effect burden: a quick guide for clinicians. Drugs in Context, 4 , 212290. doi: 10.7573/dic.212290. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26576188/

Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Richards, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77 , 42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26978184/

Sub Laban, T., & Saadabadi, A. (2020). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI). In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30969670/

Thour, A., & Marwaha, R. (2020). Amitriptyline. In StatPearls . StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30725910/

Wang, S. M., Han, C., Bahk, W. M., Lee, S. J., Patkar, A. A., Masand, P. S., & Pae, C. U. (2018). Addressing the side effects of contemporary antidepressant drugs: a comprehensive review. Chonnam Medical Journal, 54 (2), 101–112. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2018.54.2.101. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29854675/

Wichman, C. L., & Stern, T. A. (2015). Diagnosing and treating depression during pregnancy. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 17 (2), 10.4088/PCC.15f01776. doi: 10.4088/PCC.15f01776. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4560196/