Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

It’s not every day that you come across good news on a medical website, but today is that day. Chlamydia is treatable. Not only is it treatable—it’s easily treatable! In many cases, all it takes is a single dose of an antibiotic, and you’re chlamydia-free.

Now, this isn’t the case for everybody. Some people may need different kinds of antibiotics for varying lengths of time. Treatment depends on the type of chlamydia you have, how extensive the infection is, and if the chlamydia has developed any resistance to antibiotics. We’ll dive into all this in a moment but first, a quick refresher on what chlamydia is.

What is chlamydia?

Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), chlamydia is the most common reportable bacterial infection in the United States, with approximately four million cases estimated in 2018. It spreads through sexual contact, including vaginal, penile, or anal sex with an infected person (CDC, 2021).

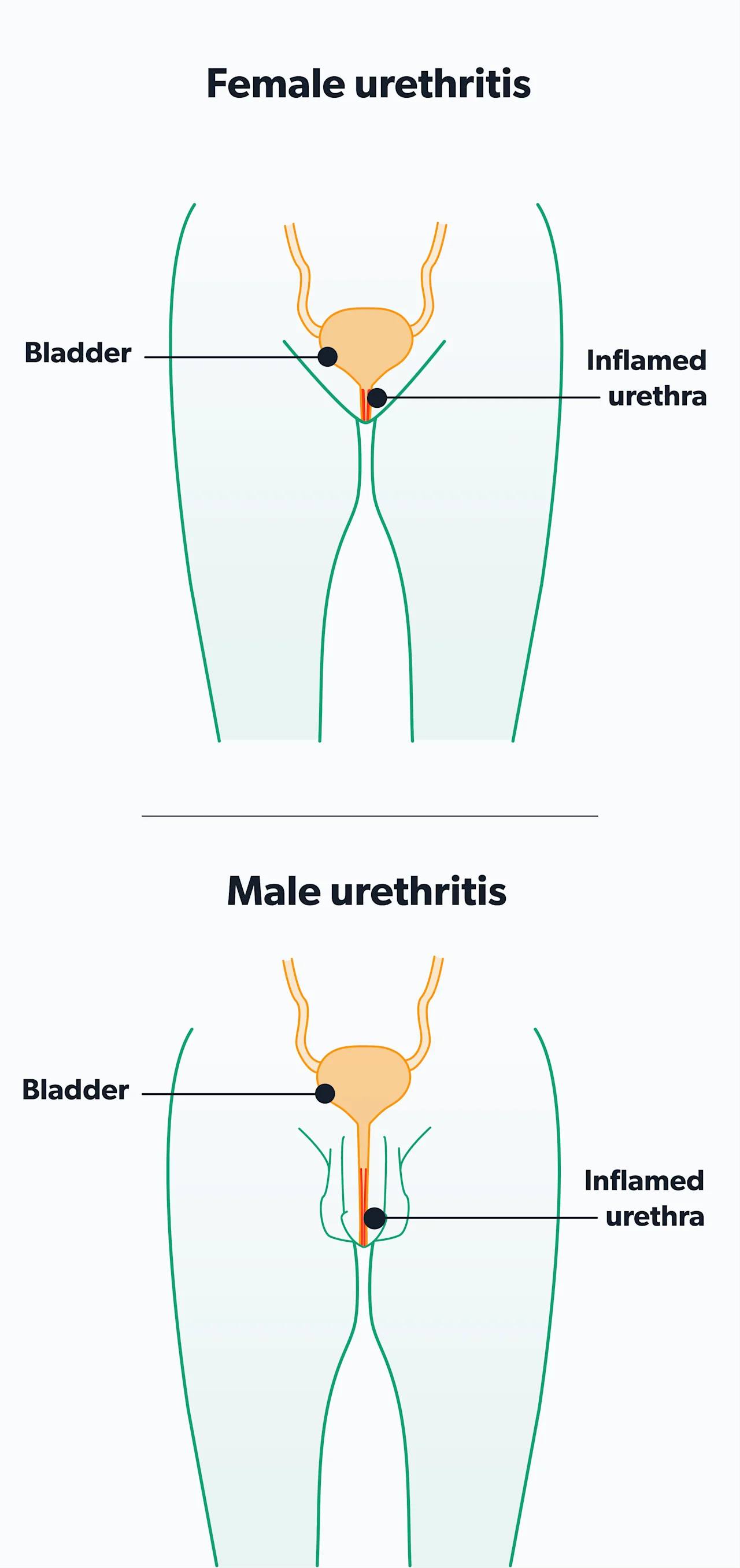

Chlamydia most commonly infects the urethra (the tube that allows urine to leave the body) or the cervix. It can also infect the throat or rectum. Less often, chlamydia can affect the prostate, epididymis (coils of tubes behind the testicles), uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. Complications of untreated chlamydia infections include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy, pelvic pain, and infertility in women. Some strains cause lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), an infection of the lymphatic system (Hsu, 2019).

While the classic symptoms of chlamydia are burning while urinating and urethral or vaginal discharge, chlamydia is asymptomatic in most cases. The best way to determine whether you have chlamydia is through screening, either at home or at your healthcare provider’s office. At-home testing is available on the internet, but the FDA has not formally approved these tests.

How is chlamydia treated?

According to the current chlamydia treatment guidelines, there are three situations in which you may find yourself getting antibiotics:

You have symptoms consistent with a chlamydial infection.

A sexual partner has contacted you and let you know that they tested positive for chlamydia.

You were screened for STIs and found out you have chlamydia, even though you may or may not be experiencing any symptoms.

In these first two situations, treatment for chlamydia is often presumptive (called empiric therapy). Presumptive treatment means that you will receive treatment even before your test results come back. It's beneficial because it treats you sooner, reducing the need to return to your healthcare provider for an extra visit. It also reduces the amount of time you may continue to spread the infection to others.

Additionally, the treatment for chlamydia is generally well-tolerated and low-cost (or even free in some places), so the downsides of presumptive treatment are minimal. The first-line treatment for chlamydia is one of two antibiotics: azithromycin (brand name Zithromax) or doxycycline (brand name Vibramycin). Azithromycin treatment is a one-time dose of 1 g. Doxycycline treatment is seven days of 100 mg taken twice daily (Hsu, 2021).

Alternative antibiotic options include two fluoroquinolone antibiotics called levofloxacin (brand name Levaquin) or ofloxacin (brand name Floxin). However, these therapies may be more expensive and should only be used in certain patient populations (Hsu, 2021).

When you are treated presumptively for chlamydia, your healthcare provider may also treat you for gonorrhea, which frequently infects individuals along with chlamydia. The treatment for gonorrhea includes a one-time injection of an antibiotic called ceftriaxone (brand name Rocephin). Treatment for gonorrhea always includes azithromycin, even if chlamydia comes back negative (Hsu, 2021).

Specific diseases caused by chlamydia may require a longer course of antibiotics (Hsu, 2021):

If an individual has epididymitis, doxycycline may be given for ten days.

If an individual has LGV, doxycycline may be given for 21 days.

If an individual has PID, doxycycline may be given for 14 days.

In recent years, there has been concern regarding the emergence of drug resistance or antibiotic resistance amongst certain bacteria. In particular, super drug-resistant gonorrhea, sometimes called “super gonorrhea,” has been capturing headlines. While strains of drug-resistant chlamydia have begun emerging in parts of the world, at this time it is still recommended that azithromycin or doxycycline are used as treatment (Hsu, 2021).

Of note, people who are HIV positive (positive for human immunodeficiency virus) should receive the same treatment as patients who are not HIV positive.

How is chlamydia treated in pregnant women?

Doxycycline, levofloxacin, and ofloxacin are all contraindicated in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. Because of this, the recommended treatment is a one-time dose of azithromycin. If azithromycin is not well-tolerated, alternative treatments include amoxicillin (brand name Amoxil) or one of several formulations of erythromycin (Hsu, 2021).

Pregnant women who have been treated for chlamydia should return after three weeks to be retested to establish that they have been cured. They should return again after three months to evaluate for reinfection. Untreated chlamydia in pregnant women can lead to early rupture of the fluid sac containing the fetus and premature delivery. It can also lead to pneumonia or conjunctivitis (an eye infection) in the newborn (Hsu, 2021).

What is reinfection with chlamydia? How can it be prevented?

Reinfection refers to a situation in which somebody has been treated for chlamydia, but then gets chlamydia again in the future. It is recommended that patients return for testing after three months to see if they have been reinfected. In patients who have persistent symptoms or who were treated with an inferior antibiotic (such as amoxicillin or erythromycin), repeat testing should be done after three weeks to ensure the bacteria is no longer present.

Reinfection usually occurs because of continued contact with an untreated sexual partner. Reinfection is not uncommon; in fact, 15–30% of sexually active women become reinfected with chlamydia. One way to avoid reinfection is to avoid sexual activity within seven days after starting antibiotic treatment. This will both help prevent the further spread of chlamydia and will reduce the risk that somebody will get chlamydia who could pass it back to you again (Hsu, 2021).

Another way to avoid reinfection is to make sure all of your sexual partners within 60 days are made aware that they might have chlamydia. This should prompt them to be tested and treated as well. In some areas of the country, public health workers may assist in notifying sexual partners (Hsu, 2021).

One practice that is intended to help treat sexual partners is called expedited partner therapy (EPT) or patient-delivered partner therapy (PDT or PDPT). This practice goes beyond just notifying partners that they might have chlamydia. With EPT, antibiotic treatment for a sexual partner is given to a patient or is directly called into a pharmacy for the partner, without a healthcare provider ever examining the partner (Hsu, 2021).

For example, suppose you are diagnosed with chlamydia. In that case, you may be given an extra dose of antibiotics to take home and give to your sexual partner, without your sexual partner ever needing to go to a healthcare provider. This is intended to increase treatment amongst sexual partners, decrease reinfection rates, and reduce the overall burden of disease in society.

What are the complications of untreated chlamydia?

If left untreated, chlamydia can lead to several complications in men and women.

In men, chlamydia can infect the prostate and the epididymis, leading to pain. It can also be a cause of urethral strictures (narrowing of the urethra), can lead to issues in the rectum (such as narrowing or abnormal connections), and can trigger an immune response known as reactive arthritis or Reiter’s syndrome.

In women, untreated chlamydia can spread to the reproductive organs causing PID, which can lead to infertility, pelvic pain, and increased risk of ectopic pregnancy. It can also spread to the lining of the liver, causing perihepatitis (also called Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome) and adhesions and scarring around the organs in the abdomen.

When can you have sex again?

If your healthcare provider has told you that you have (or are suspected of having) chlamydia and starts you on antibiotic therapy, you should avoid vaginal, anal, and oral sex for seven days after beginning treatment. Also, be sure to inform all of your sexual partners within the past 60 days and encourage them to get treatment—your provider's office may be able to help you with this.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021, Jan). Chlamydia - CDC fact sheet (detailed). Retrieved on May 6, 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia-detailed.htm

Hsu, K. (2019). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. In UptoDate . Marrazzo, J. and Bloom, A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-chlamydia-trachomatis-infections

Hsu, K. (2021). Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. In UptoDate . Marrazzo, J. and Bloom, A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-chlamydia-trachomatis-infection