Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Reading an online article about chlamydia in men probably isn’t what you thought you would be doing today. Whatever it is that brings you here—whether you have symptoms or just want a refresher on your “sex ed” class from high school—we’re here to help.

What is chlamydia?

When you learned about chlamydia in school, it was probably mentioned alongside gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and human papillomavirus (HPV). It’s caused by the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis.

Chlamydia is more common than most other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), with an estimated four million cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2018. This makes it the most common reportable bacterial infection in the United States. Part of why chlamydia is so common is that it’s most often asymptomatic. That means you or somebody you know may be infected without even knowing it (CDC, 2021).

How does chlamydia spread in men?

Chlamydia is transmitted from person to person through sexual contact. More specifically, chlamydia is spread by touching an infected partner's anus, mouth, penis, or vagina. This includes having anal sex, oral sex, and vaginal sex. Chlamydia cannot be spread through kissing (mouth-to-mouth contact), but an infection of the throat can spread to a partner who is receiving oral sex.

Signs and symptoms of chlamydia in men

Most cases of chlamydia in men have no symptoms. Current estimates indicate that only 10% of men develop symptoms of chlamydia—these symptoms do not show up immediately when they do occur. It usually takes around 5–10 days after exposure to chlamydia for symptoms to begin. When symptoms or other health problems develop, chlamydia is referred to as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) (Hsu, 2019).

The symptoms discussed here refer to those that cis-gendered men may experience. If you are a transgender man, depending on your anatomy, the symptoms related to you may be described here or in our related article on women and chlamydia. The body parts discussed here are the urethra, epididymis, prostate, lymph nodes, rectum, and throat.

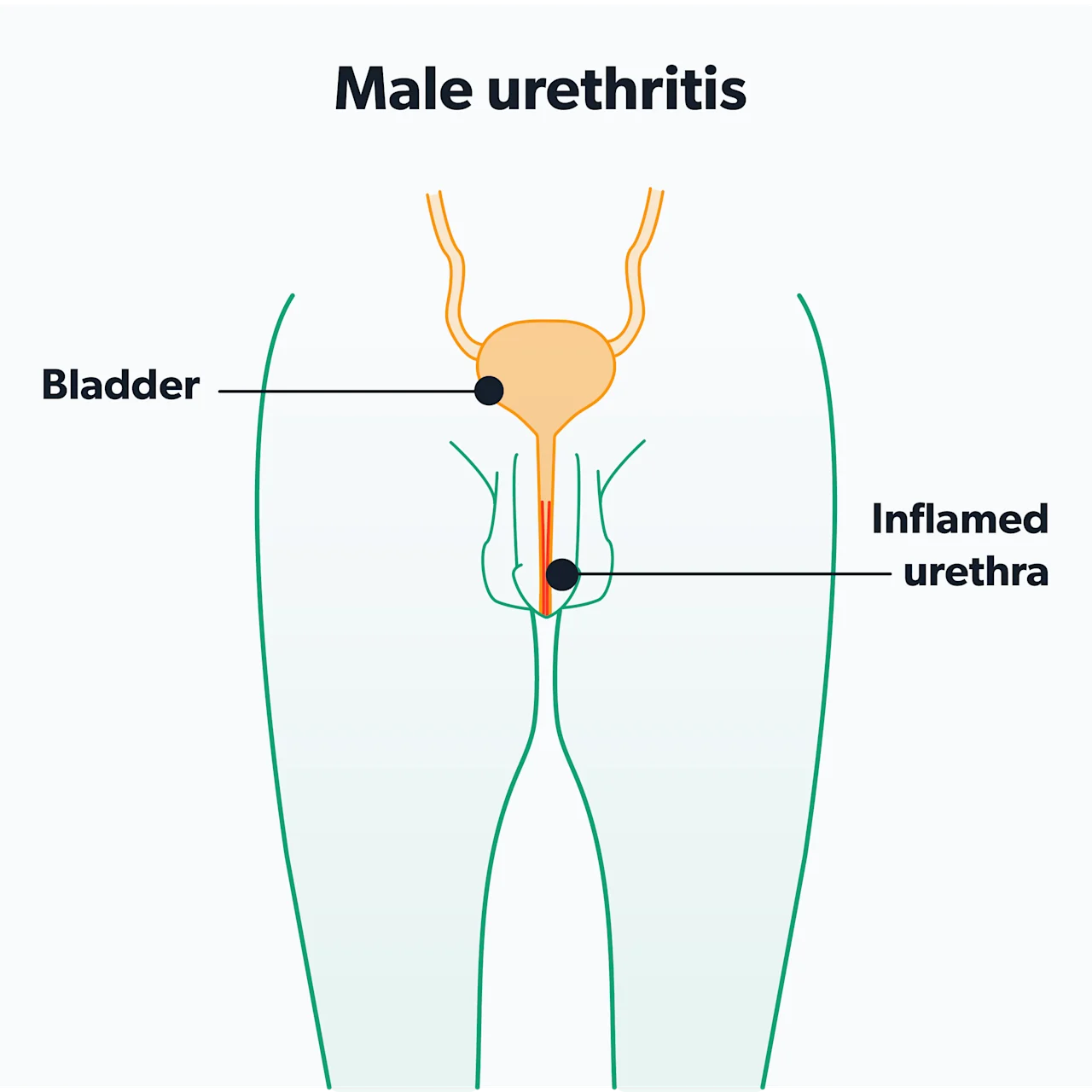

Urethra

Chlamydia in men most commonly infects the urethra—the tube that runs inside the penis and allows semen and urine to exit the body. Infection of the urethra is called urethritis. You may see it also referred to as non-gonococcal urethritis, which means urethritis caused by something other than gonorrhea. The most common symptoms of urethritis are (Hsu, 2019):

Frequent urination

Burning or pain while urinating (dysuria)

Itchy feeling near the opening of the penis

Scant, watery, white discharge (as opposed to the more goopy, pus-like discharge of gonorrhea)

You may experience all, some, or none of these symptoms. Some men notice the discharge as a dried film on the tip of the penis if they have not urinated for a while or as a stain on the inside of their underwear.

Epididymis

More rarely, chlamydia can infect the epididymis, which is the coiled tube filled with sperm attached to the back of each testicle. Infection of the epididymis is called epididymitis and can cause (Hsu, 2019):

Swelling of the scrotum on one or both sides

Testicle pain or soreness on one or both sides

Prostate

Chlamydia may also be one of the infections that may contribute to chronic prostatitis, which is long-term inflammation of the prostate gland. Symptoms of prostatitis include (Hsu, 2019):

Pain with urination

Pain with ejaculation

Incontinence

Difficulty urinating

Pelvic pain

Lymph nodes

Chlamydia trachomatis is one species of bacteria, but it comes in several subtypes, called serovars. Serovars D–K cause the symptoms we have already discussed. However, serovars L1, L2, and L3 cause a separate disease called lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). LGV is also an STI and is spread in the same way the typical chlamydia infection is spread.

LGV is an infection of the lymphatic system and requires more aggressive treatment than serovars D–K. Symptoms include (Hsu, 2019):

A painless ulcer at the site where the infection entered the body (although this does not always occur)

Painful swelling of the lymph nodes in the groin

Typically, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is found in heterosexuals in tropical and subtropical regions (Africa, the Caribbean, India, and Southeast Asia). However, since 2003, outbreaks have been seen in North America and Western Europe. These outbreaks are primarily amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) and those who also have HIV (de Vries, 2019).

Rectum

If you engage in receptive anal sex, you are also at risk for developing proctitis, which is infection and inflammation of the lining of the rectum. When caused by serovars D–K, proctitis is often asymptomatic. However, proctitis in MSM has been seen with serovars L1, L2, and L3 (the same serovars that cause LGV), which can be a much more serious condition. Symptoms include (Hsu, 2019):

Rectal pain

Rectal discharge

Rectal bleeding

Constipation

Tenesmus (the sensation of needing to have a bowel movement)

Throat

Chlamydia can infect the throat, referred to as pharyngeal chlamydia or oral chlamydia. This is typically asymptomatic but may cause a sore throat in some people. If you engage in oral sex, you can pass oral chlamydia to your sex partner's genitals.

What are the complications of untreated chlamydia in men?

Because most men with chlamydia do not develop symptoms, many don’t realize they have it and don’t get the appropriate treatment. If left untreated, chlamydia infections may cause complications in men, including infertility, an abnormal narrowing of the rectum or urethra, and arthritis.

Untreated epididymitis from chlamydia may lead to infertility via two potential mechanisms (Gallegos, 2008):

First, it has been suggested that untreated epididymitis can lead to scarring of the ducts that carry sperm.

Secondly, chlamydia may directly impact the sperm and cause changes in sperm DNA.

However, a 2017 study found that infection with chlamydia did not harm sperm, nor did it affect fertility (Suarez, 2017).

On the other hand, untreated proctitis caused by serovars L1, L2, or L3 does lead to long-term complications. Without appropriate antibiotic treatment, proctitis can cause fistulas (abnormal connections between the intestines and the skin) and strictures (areas of narrowing at risk for blockage) of the rectum (Hsu, 2019).

Chlamydia may also be a cause of urethral stricture disease in men. This is a condition in which the urethra narrows, which can cause several issues with urination (pain, blood, decreased stream, etc.). Surgery may be necessary to correct urethral stricture disease (Trei, 2008).

Lastly, in men who have urethritis, chlamydia can cause an immune reaction called reactive arthritis—this occurs in approximately 1% of men with urethritis. Reactive arthritis can cause pain, swelling, redness, and stiffness of the joints. It typically affects the knees, ankles, and feet but can also occur in other joints. People with reactive arthritis may also experience lower back pain, pain where tendons and ligaments connect to the bone (called enthesitis), and swollen “sausage fingers” (called dactylitis) (Yu, 2021).

Several types of bacterial infections can cause reactive arthritis, but chlamydia is one of the most common. Some people with urethritis and arthritis also develop conjunctivitis or uveitis (inflammation of parts of the eye that causes blurred vision). This triad of symptoms of urethritis, arthritis, and eye inflammation is called Reiter’s syndrome.

Testing for chlamydia in men

Diagnosing chlamydia in men involves getting a sample from every area at risk of infection—this will depend on the type of sex you engage in or the symptoms you are experiencing. In men, this usually means a urine sample. Healthcare providers often specify that this should be a “first catch” sample to indicate that urine from the beginning of the stream should be evaluated in the chlamydia test.

If you have engaged in oral sex or receptive anal sex, you can ask your provider to check a throat swab or rectal swab, respectively.

Screening can help detect chlamydia, especially since most people don't develop chlamydia symptoms. Men who have sex with men should be screened as frequently as every 3–6 months. However, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that there isn’t enough evidence to support or reject screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea in other sexually active men (USPSTF, 2021).

If you are interested in getting screened, talk to your healthcare provider. In the meantime, staying aware of the symptoms of chlamydia and how it spreads is an excellent step for your sexual health.

Treating chlamydia in men

If you are exhibiting symptoms or you have a sexual partner who has already tested positive, you will likely be given treatment for chlamydia even before your test results come back (this is called presumptive treatment).

Chlamydia is treated with antibiotics, often a single dose of azithromycin (brand name Zithromax). If there is a concern for a possible co-infection with gonorrhea, you’ll also get a single injection of an antibiotic called ceftriaxone (brand name Rocephin). This is typically the case when treatment is presumptive (Hsu, 2021).

An alternative first-line treatment regimen is a 7-day course of doxycycline (brand name Vibramycin). This replaces the single dose of azithromycin. If you have additional issues, like epididymitis or LGV, you may need a longer treatment course (Hsu, 2021).

How to prevent chlamydia in men?

Using barrier methods, like condoms or dental dams, during all forms of sex can lower your risk of getting chlamydia. Other forms of contraception, like partial barriers (e.g., diaphragms), birth control pills, IUDs, etc., do not prevent the spread of STIs like chlamydia. Unprotected sex, unsurprisingly, increases your chances of getting chlamydia and other STIs.

Approximately 10–18% of men get reinfected with chlamydia—this means that you have been treated for chlamydia but get chlamydia again in the future. Your healthcare provider may recommend repeat testing three months after treatment to check for reinfection (Hsu, 2021).

Reinfection most often occurs because of continued contact with an untreated sexual partner. The best way to avoid reinfection is to abstain from sexual activity for seven days after starting antibiotic treatment. This will reduce the risk that your sex partner will get chlamydia and then pass it back to you (Hsu, 2021).

It’s recommended to notify all of your sexual partners within the past 60 days that they might have chlamydia so that they can get tested and treated. Depending on where you live, public health workers may be available to help you reach out to your sexual partners (Hsu, 2021).

When to see your healthcare provider

If you suspect that you have chlamydia or if you have a sex partner recently diagnosed with chlamydia (or any other STI), talk to your healthcare provider. You may need testing not only for chlamydia but also for other STIs, like gonorrhea, that may be spread along with chlamydia. Also, if you are being treated for an STI and your symptoms are not improving, seek medical advice. Your healthcare provider will work with you to make sure you take care of your sexual health.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, Jan). Chlamydia - CDC fact sheet (detailed). Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia/stdfact-chlamydia-detailed.htm

de Vries, H., de Barbeyrac, B., de Vrieze, N., Viset, J. D., White, J. A., Vall-Mayans, M., et al. (2019). 2019 European guideline on the management of lymphogranuloma venereum. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV, 33(10), 1821–1828. doi: 0.1111/jdv.15729. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31243838/

Gallegos, G., Ramos, B., Santiso, R., Goyanes, V., Gosálvez, J., & Fernández, J. L. (2008). Sperm DNA fragmentation in infertile men with genitourinary infection by Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma. Fertility and Sterility, 90(2), 328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.035. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17953955/

Hsu, K. (2019). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. In UptoDate. Marrazzo, J. and Bloom, A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-chlamydia-trachomatis-infections

Hsu, K. (2021). Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. In UptoDate. Marrazzo, J. and Bloom, A. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-chlamydia-trachomatis-infection

Suarez, J. P., Sanchez, L. R., Salazar, F. C., Saka, H. A., Molina, R., Tissera, A., et al. (2017). Chlamydia trachomatis neither exerts deleterious effects on spermatozoa nor impairs male fertility. Scientific Reports, 7, 1126. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01262-w. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28442719/

Trei, J. S., Canas, L. C., & Gould, P. L. (2008). Reproductive tract complications associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection in US Air Force males within 4 years of testing. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 35(9), 827–833. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181761980. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18562984/

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2021). Draft recommendation statement: Screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Retrieved May 11, 2021 from https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/chlamydial-and-gonococcal-infections-screening

Yu, D.T. and van Tubergen, A. (2021). Reactive arthritis. In UptoDate. Sieper, J. and Romain, P.L. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/reactive-arthritis