Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Prozac (fluoxetine) has been used to treat depression since the 1980s, so many people have heard of it and recognize it as an antidepressant. Since then, many more antidepressants have come onto the scene, and it can be tough to know the differences between them. Lexapro (escitalopram) is another popular antidepressant, but what do you know about it, and how does it compare to Prozac?

What are Lexapro and Prozac?

Depression has become one of the most common mental health disorders in the U.S., with over 17 million adults reporting at least one episode of depression in 2017 (NIMH, 2019). The symptoms of depression can make it difficult to get through your normal day's activities. As rates of depression have gone up, so has antidepressant use.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate that over 13% of American adults have taken antidepressants in the past 30 days (Brody, 2020). While these medicines are common, it can be challenging to understand the differences between one antidepressant and another.

Both Prozac and Lexapro are prescription antidepressant medications called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs. These drugs increase serotonin levels, a neurotransmitter in the brain and nervous system essential for a healthy mood. Other commonly prescribed SSRIs include citalopram (brand name Celexa) and sertraline (brand name Zoloft).

Your healthcare provider may recommend SSRIs, as they are the most commonly used drugs to treat depression (Chu, 2021). However, if you’re discussing these medications with your healthcare provider, you need to know how they compare, especially regarding their side effects, drug interactions, and uses.

What is Lexapro?

Lexapro is the brand name for the generic drug escitalopram oxalate. It is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat major depressive disorder (MDD) in people over 12 years of age and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in adults (FDA, 2017-a).

Sometimes, healthcare professionals use medications to help with conditions that they are not FDA-approved to treat—this is called using a drug “off-label.” In the case of Lexapro, off-label uses include the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), binge-eating disorder (BED), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), among other conditions (UptoDate, n.d.-a).

What is Prozac?

Prozac is the brand name for fluoxetine hydrochloride. This prescription drug is FDA-approved to treat major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in children and adults, as well as for bulimia nervosa and panic disorder in adults (FDA, 2017-b).

Some healthcare providers use Prozac in combination with olanzapine, an antipsychotic medication, to treat the depressive episodes of bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is when you swing from extremely low, depressed moods to extremely high, manic moods. Bipolar depression is different from the depression experienced in MDD, also called unipolar depression. There are also several off-label uses discussed below.

The combination of Prozac and olanzapine may also help people with treatment-resistant depression (MDD that has not responded to treatment with two different antidepressants) (FDA, 2017-b).

What conditions do Lexapro and Prozac treat?

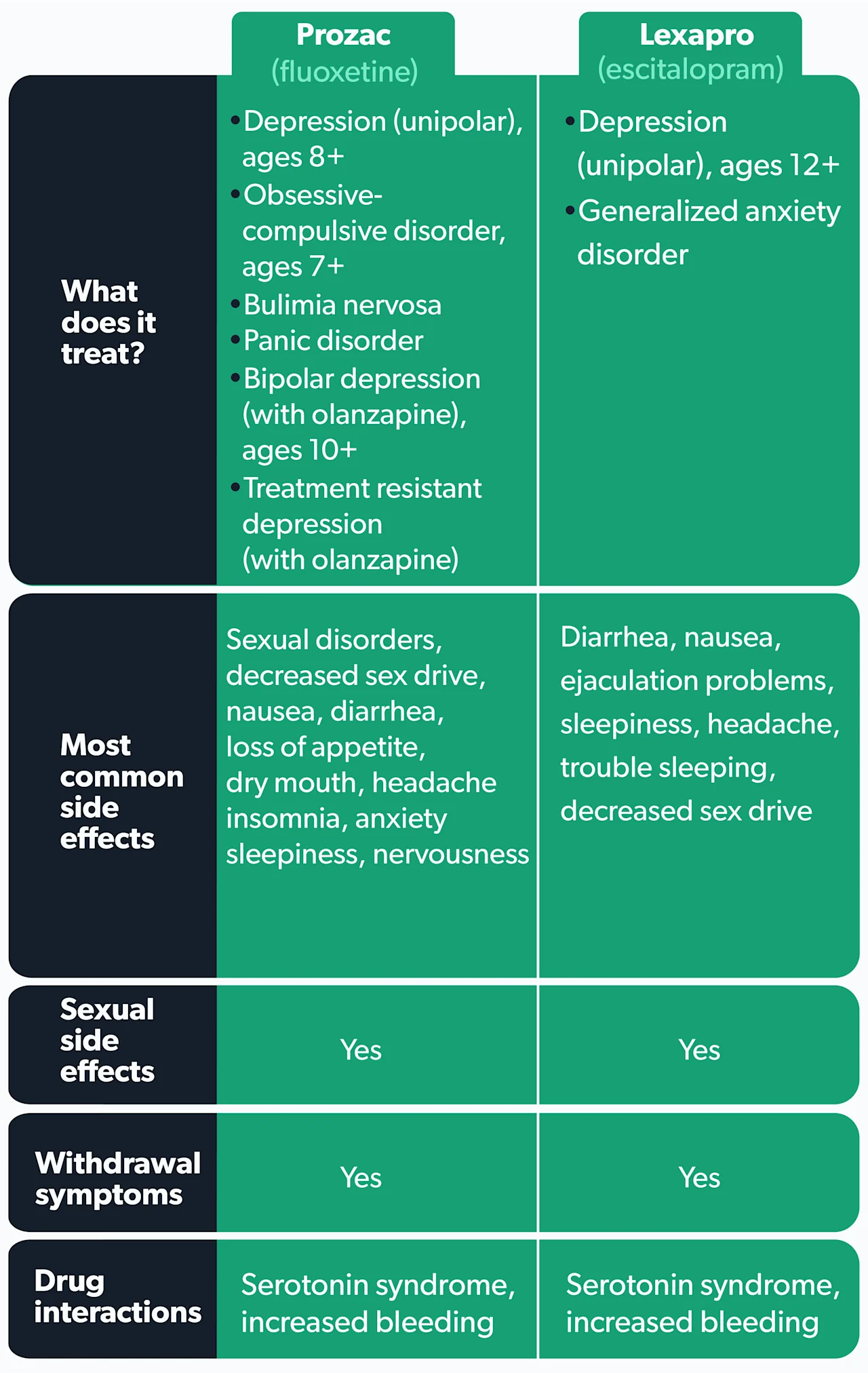

While both Lexapro and Prozac treat depression, there are some differences in the other FDA-approved and off-label conditions treated by these drugs.

Lexapro uses

FDA-approved uses include (FDA, 2017-a):

Major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults and adolescents over age 12 (short-term and long-term treatment)

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in adults (short-term treatment)

Off-label (not FDA-approved) uses include (UptoDate, n.d.-a):

Body dysmorphic disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in adults, adolescents, and children over age six

Panic disorder

Prozac uses

FDA-approved uses include (FDA, 2017-b):

Major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults and children over age eight (short-term and long-term treatment)

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in adults and children over age seven (short-term and long-term treatment)

Bulimia nervosa (short-term and long-term treatment)

Panic disorder (short-term treatment)

Bipolar depression, in combination with olanzapine, in adults and children over age 10 (short-term treatment)

Treatment-resistant depression in combination with olanzapine

Off label (not FDA-approved) uses include (UptoDate, n.d.-b):

Binge eating disorder

Fibromyalgia

Generalized anxiety disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Premature ejaculation

Social anxiety disorder

Side effects of Lexapro and Prozac

All SSRIs share some common side effects. The most common side effects across the SSRI drug class include sexual dysfunction, trouble sleeping, weight changes, anxiety, dizziness, dry mouth, headache, and stomach upset (Hirsch, 2020-a)

While it may seem counterintuitive, in rare cases, children, adolescents, and young adults are at an increased risk of worsening depression symptoms and suicidal thoughts when taking SSRIs (FDA, 2018). Therefore, the FDA has issued a black box warning regarding this potential risk—be on the lookout for any changes in behavior or mental health, including worsening depression, panic attacks, and suicidal thoughts when starting either medication or when your healthcare provider changes your dose.

Sexual side effects

Unfortunately, sexual dysfunction is a common side effect of these antidepressants, with an estimated 50% of people noting sexual dysfunction while taking SSRIs (Hirsch, 2019)

The SSRI that appears to cause the most sexual side effects is paroxetine (brand name Paxil). One study looked at 344 subjects on different SSRI medications and found the medications that caused the most sexual side effects from most to least were paroxetine, fluvoxamine (brand name Luvox), sertraline (Zoloft), and fluoxetine (brand name Prozac and Sarafem) (Jing, 2016).

However, you may experience less sexual dysfunction while taking Prozac compared to Lexapro. In clinical trials, lowered sex drive was the only symptom of Prozac present in more than 2% of the participants—the frequency cutoff for considering a side effect common (FDA, 2017-b). In trials on Lexapro, on the other hand, men experienced adverse effects including ejaculation disorder (delayed ejaculation), lowered sex drive, and impotence (erectile dysfunction) (FDA, 2017-a).

In women, both of these SSRIs caused a decrease in libido. Lexapro caused women to experience an inability to orgasm in 2% of participants, while those on Prozac only noted this adverse effect intermittently (FDA, 2017-a; FDA, 2017-b).

Overall, the rate of sexual dysfunction is likely less than the actual values—most people are not comfortable talking about this side effect with their healthcare providers. However, if you experience sexual problems on either of these medications, don’t be afraid to speak up. In some cases, antidepressants like bupropion, mirtazapine, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) like duloxetine (brand name Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (brand name Effexor) may be alternative treatment options.

But if you are one of those people who only respond to SSRIs, adding bupropion (the generic name for Wellbutrin) may help improve these side effects (Jing, 2016).

Withdrawal symptoms

Make sure to consult with your healthcare provider before stopping either Lexapro or Prozac. Abruptly discontinuing these drugs may cause withdrawal symptoms, including dizziness, nausea, headache, fatigue, mood changes, insomnia, and paresthesias (a prickling or tingling sensation on the skin) (Hirsch, 2020-b).

Work with your healthcare provider to slowly reduce your dose of these medications to avoid this discontinuation syndrome. Most people experience withdrawal symptoms of SSRIs within one week of stopping, and they usually improve a few weeks later (Hirsch, 2020-b).

Prozac side effects

Compared to clinical trials done on Lexapro, studies done on Prozac revealed more possible side effects. They also showed higher frequencies of some of these side effects. Some of the most common side effects of Prozac include (UptoDate, n.d.-b):

Sexual disorder (ejaculation problems, inability to orgasm, etc.)

Decreased sex drive

Nausea

Diarrhea

Loss of appetite

Dry mouth

Headache

Insomnia

Anxiety

Sleepiness

Nervousness

Many of the side effects of Prozac appear to be dose-dependent—meaning, higher doses seem to cause higher rates of many side effects, including nausea, weakness, and insomnia (FDA, 2017-b).

Lexapro side effects

Like Prozac, how many and how frequently you experience side effects on Lexapro may depend on the dose you’re taking. More people experienced side effects while taking 20 mg than those on a 10 mg dose in clinical trials. In people using Lexapro for major depression, some of the most common side effects include (UptoDate, n.d.-a):

Diarrhea

Nausea

Ejaculation problems

Sleepiness

Headache

Trouble sleeping

Decreased sex drive (libido)

Some people stop taking Lexapro due to the side effects, and this also seems to be dose-dependent—more people on 20 mg stopped taking Lexapro than those on 10 mg (FDA, 2017-a).

Potential drug interactions

Several serious drug interactions may happen if you combine either of these SSRI drugs with other specific medications. One drug interaction is serotonin syndrome, a condition where too much serotonin builds up in the body. Serotonin syndrome may cause shivering, high blood pressure, elevated heart rate, fever, diarrhea, or more severe symptoms like seizures, coma, or death (Simon, 2021).

Both Lexapro and Prozac work by increasing serotonin levels in the body, and levels may quickly reach dangerous levels when combined with other medications that also raise serotonin (Simon, 2021).

Drugs that you should avoid while taking Prozac and Lexapro include monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants (like amitriptyline), fentanyl, tryptophan, tramadol, buspirone, amphetamines, and over-the-counter supplements containing St. John’s wort (Simon, 2021).

Combining Lexapro or Prozac with medications like over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen may increase your risk of bleeding. This also includes prescription blood thinners such as warfarin (brand name Coumadin). Talk to your healthcare provider before taking any of these medications while on either of these SSRIs (FDA, 2017-a; FDA, 2017-b).

Both of these medications may also cause sleepiness and affect your ability to think, react quickly, or make decisions. Alcohol has these effects as well. Though neither of these medications has been shown to amplify those effects when combined with alcohol, it’s still standard medical advice to avoid drinking when taking either of these medications (FDA, 2017-a; FDA, 2017-b).

This list does not include all of the possible drug interactions with Prozac or Lexapro—talk to your healthcare provider or pharmacist if you have any questions.

Differences and similarities of Prozac vs. Lexapro

We’ve given you a lot of information about the differences and similarities between these two SSRIs medications. Here is a summary of characteristics:

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Brody, D. J. & Gu, Q. (2020). Antidepressant use among adults: the United States, 2015–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 377. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from h ttps://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db377.htm

Chu, A. & Wadhwa, R. (2021). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. [Updated May 10, 2021]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2017-a, Jan). Lexapro (escitalopram oxalate). Retrieved June 15, 2021 from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/021323s047lbl.pdf

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2017-b, Jan). Prozac (fluoxetine hydrochloride) capsules label. Retrieved June 15, 2021 from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/018936s108lbl.pdf

Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2018, Feb). Suicidality in children and adolescents being treated with antidepressant medications. Retrieved June 15, 2021 from https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/suicidality-children-and-adolescents-being-treated-antidepressant-medications

Hirsch, M. & Birnbaum, R. J. (2019). Sexual dysfunction caused by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): management. In UptoDate . Roy-Byrne, P.P. & Solomon, D. (Eds.). Retrieved from ttps://www.uptodate.com/contents/sexual-dysfunction-caused-by-selective-serotonin-reuptake-inhibitors-ssris-management

Hirsch, M. & Birnbaum, R. J. (2020-a). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: pharmacology, administration, and side effects. In UptoDate . Roy-Byrne, P.P. & Solomon, D. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/selective-serotonin-reuptake-inhibitors-pharmacology-administration-and-side-effects

Hirsch, M. & Birnbaum, R. J. (2020-b). Discontinuing antidepressant medications in adults. In UptoDate . Roy-Byrne, P.P. & Solomon, D. (Eds.). Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/discontinuing-antidepressant-medications-in-adults

Jing, E. & Straw-Wilson, K. (2016). Sexual dysfunction in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and potential solutions: A narrative literature review. Mental Health Clinician, 6 (4), 191-196. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.07.191. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6007725/

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). (2019, Feb). Major depression. Retrieved on June 15, 2021 from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression

Simon, L. V. & Keenaghan, M. (2021). Serotonin syndrome. [Updated Jul 22, 2021]. In StatPearls . Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482377/

UptoDate. (n.d.-a). Escitalopram: drug information. Retrieved on June 15, 2021 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/escitalopram-drug-information

UptoDate. (n.d.-b). Fluoxetine: drug information. Retrieved on June 15, 2021 from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/fluoxetine-drug-information