Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers in men. If you or someone you know has been diagnosed with it, you probably have many questions. Experts don’t have all the answers but read on to learn more about prostate cancer symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options.

What is prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men, aside from skin cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, about 1 in 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer. It’s also the second leading cause of cancer deaths in this group, behind lung cancer (ACS, 2021).

As frightening as these numbers may seem, it’s important to remember that most people diagnosed with prostate cancer will not die from their disease.

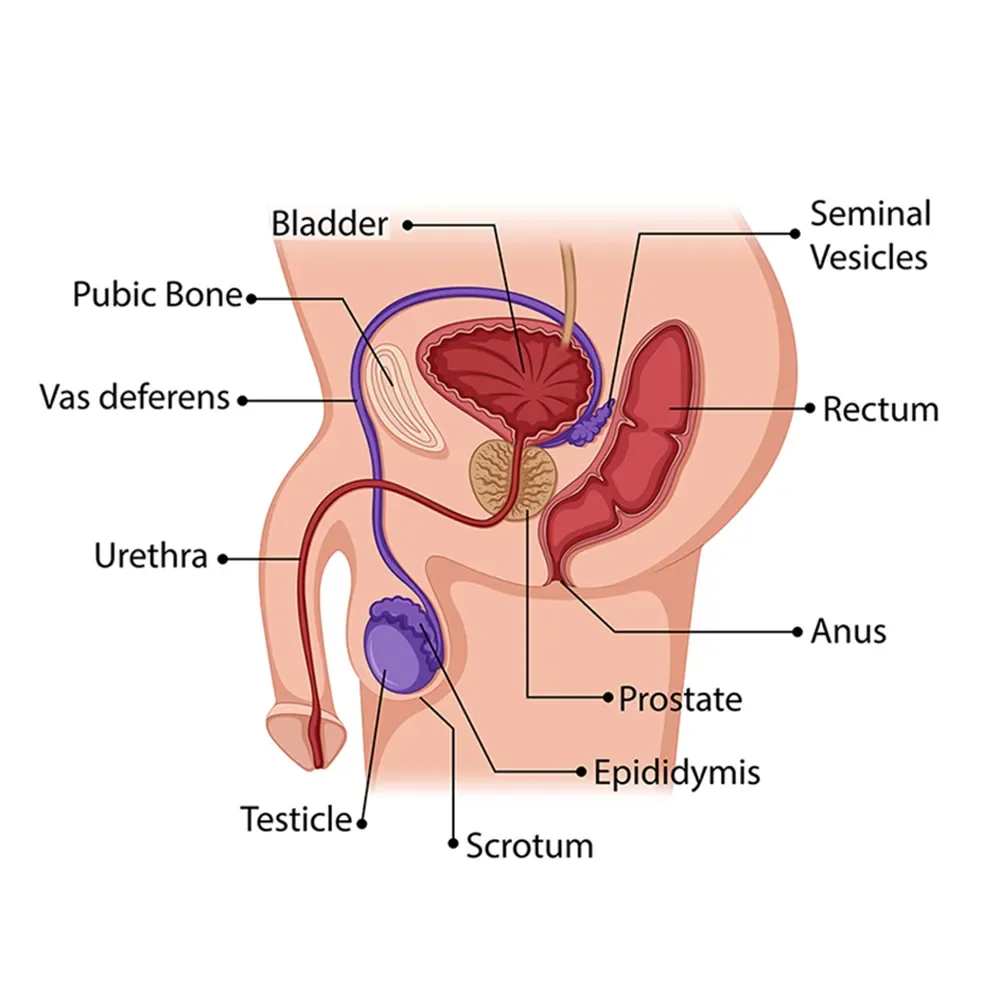

What is the prostate?

The prostate is a small gland located below the bladder and in front of the rectum. In younger men, it’s about the size of a walnut; the prostate typically gets larger as you age (Ng, 2021).

The prostate's job is to produce and secrete prostatic fluid, one of the components of semen. This fluid both nourishes and transports sperm (Singh, 2021).

Prostate cancer symptoms

The prostate lives between several other structures, including the bladder, rectum, penis, and urethra. When it grows, it can cause different symptoms. That said, early-stage prostate cancer doesn't usually cause symptoms.

Prostate cancer grows slowly and may not cause symptoms for years—or ever. That's why so many men can have prostate cancer and not know it.

When symptoms do arise, it’s usually due to the growing prostate pressing on other structures like the urethra, which can cause lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), including (Leslie, 2021):

Urinating frequently

Feeling the need to urinate often at night (nocturia)

Trouble starting and maintaining a steady stream

Blood in your urine (hematuria)

Pain with urination (dysuria)

However, LUTS often come from benign conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostatitis.

Another way prostate cancer causes symptoms is by spreading to distant organs. Prostate cancer can permeate into bones, including the spine and ribs. In these cases, pain is the most common sign. This pain is often present in any position and is sometimes worse at night. If the spinal cord is affected, you may experience leg weakness or numbness (Leslie, 2021).

In short, symptoms alone are not enough to diagnose someone with prostate cancer. That said, no matter the cause of these symptoms, none are considered "normal" and should be discussed with your healthcare provider.

Prostate cancer causes

Researchers don’t know the definitive cause of prostate cancer. It’s likely a combination of environmental exposure, risk factors, and genetic changes.

All cancers are ultimately caused by genetic mutations or changes to your DNA. Most people acquire these mutations over their lifetime, perhaps due to their family history, where they live, or just pure bad luck. Let’s take a look at some of the potential prostate cancer causes.

Acquired gene mutations

Gene mutations allow cancers to overcome the mechanisms that normal cells have to prevent them from growing out of control. Mutations can happen during DNA replication before cells divide or can be caused by environmental factors that damage DNA, such as smoking cigarettes and exposure to ultraviolet light.

As time goes on, your cells continue to copy themselves and reproduce. The problem is that not every copy is perfect. If there’s an error, it gives cancer cells room to grow. Then that error is passed on to the next generation, and so on. A single mutation does not usually cause a cell to become cancerous; it’s the buildup of mutations over time. Especially when undetected, mutations enable cancer cells to grow and spread unchecked.

Inherited gene mutations

Mutations that increase the risk of prostate cancer can also be inherited. Scientists have identified over 100 potential sites of genetic mutations that can lead to prostate cancer—and those are only the ones they’ve found so far (Leslie, 2021).

Two examples are mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. BRCA1 and BRCA2 are known as tumor suppressors. When functioning normally, they stop cancers from forming by repairing any damaged DNA.

BRCA gene mutations can be inherited from either parent. They are well known for increasing breast and ovarian cancer risk and some others, including prostate cancer. Not only do people with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations have a high risk of developing prostate cancer, but their cancers are often aggressive. They are also more likely to die of prostate cancer than people without these mutations (Wang, 2018).

Other genetic mutations that can cause prostate cancer include PTEN, HOXB13, ERG, ETV, and RNASEL (formerly HPC1) (Wang, 2018; Rawla, 2019).

Risk factors for prostate cancer

Based on clinical trials, the well-established risk factors for prostate cancer are age, family history, race and ethnicity, and geography. Other potential risk factors we’ll look at include obesity, diet, chemical exposures, and frequency of ejaculation (Leslie, 2021).

Age

Prostate cancer is rare before age 40 but becomes more common after 55. Why? As we age, we rack up genetic mutations. The more these mutations accumulate, the more likely enough of the right combination will develop into cancer.

So, getting older is a risk factor for acquired genetic mutations, and then these mutations go on to form cancer (Leslie, 2021; Rawla, 2019).

Family history

Not surprising, family history is another risk factor for prostate cancer. People who have a family member diagnosed with prostate cancer are more likely to develop the condition.

This is especially true if the family member is a first-degree relative like a father or brother. Those with one first-degree relative with prostate cancer have 2–3 times the risk of developing it. Having more relatives with prostate cancer or others diagnosed at a young age ups that risk even more (Leslie, 2021).

Race and ethnicity

Scientists aren’t sure why, but the data shows that having Black ancestry increases the risk of developing and dying from prostate cancer. Black people in the United States, Europe, and the Caribbean all have a higher risk of developing prostate cancer at a younger age.

Interestingly, African American people have prostate cancer at rates 40 times higher than Black people from Africa. This may be due to genetic factors, environmental factors (like diet), social factors, or a combination (Rawla, 2019).

On the flip side, Asian Americans and people of Latino/Hispanic descent are less likely to develop it compared to non-Hispanic white people (Rawla, 2019).

Geography

Prostate cancer rates are higher in North America, Europe, and Australia than in Africa or Asia. However, studies show that people of African ancestry who live in Western countries have much higher rates of prostate cancer than those who live in Africa. As noted earlier, dietary, environmental, social, and other factors might account for this trend (Rawla, 2019).

Obesity

Several studies have shown that people with obesity have a higher risk of prostate cancer and others like colon and breast cancers. One theory is that obesity leads to inflammation, which plays a role in the development and progression of cancer. Research is ongoing as scientists don’t have a definitive answer about the relationship between obesity and prostate cancer quite yet (Fujita, 2019).

Diet

The Western diet is one of the reasons proposed for the higher rates of prostate cancer in certain countries. This diet typically has a higher saturated fat intake from meat and dairy.

Researchers hypothesize that high-fat intake may lead to more inflammation or more male hormones called androgens, which heightens the chance of cancer. There may also be specific nutrients lacking in Western diets––like lycopene and selenium––that can protect against cancer (Rowles, 2017; Cui, 2017).

Vegetables like tomatoes, broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts may decrease your risk of prostate cancer. Data suggests eating a diet rich in vegetables and low in starchy carbohydrates may play a role in cancer prevention. But the research is limited and more studies are needed (Rawla, 2019; Kaiser, 2019)

Chemical exposures

Exposure to certain chemicals has been found to increase the risk of prostate cancer. These include Agent Orange (used during the Vietnam war) and bisphenol A (BPA), a component of hardened plastic (Rawla, 2019).

Frequency of ejaculation

Recent studies suggest that an increased frequency of ejaculation (whether from sex or masturbation) can decrease your risk of prostate cancer.

One study showed that people who ejaculated more than 21 times per month had a 20% less risk of developing prostate cancer than those with 4-7 ejaculations per month (Rider, 2016).

Prostate cancer screening

Routine prostate cancer screening involves what’s called a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. This blood test is used to measure your PSA levels. PSA is a protein made by cells in the prostate gland. When there is a problem with the prostate, more PSA is released. High PSA levels do not necessarily mean you have prostate cancer (Leslie, 2021).

You have probably heard of another test called the digital rectal exam (DRE). During this test, your healthcare provider gently inserts a gloved finger into the rectum and sweeps it along the wall to feel for any abnormalities in the prostate. But it’s easy to miss things, and you could have cancer despite a totally normal DRE. Many doctors rely on the PSA test and no longer perform DREs alone for prostate cancer screening (Naji, 2018).

Routine screening for prostate cancer is a complex and controversial issue. While PSA screening is more accurate, it has not been found to decrease mortality, even though more people are diagnosed with prostate cancer if they’re screened (Fenton, 2018).

Cancer screening risks

Routine screening comes with its own risks. Overdetection in a routine screening can lead to overdiagnosis, which in turn leads to overtreatment.

Unfortunately, the side effects from some treatments often cause more problems than the disease itself. Side effects from screening include (Leslie, 2021):

Infections

Bleeding

Urinary problems due to biopsies

Urinary or fecal incontinence

Sexual issues, like erectile dysfunction

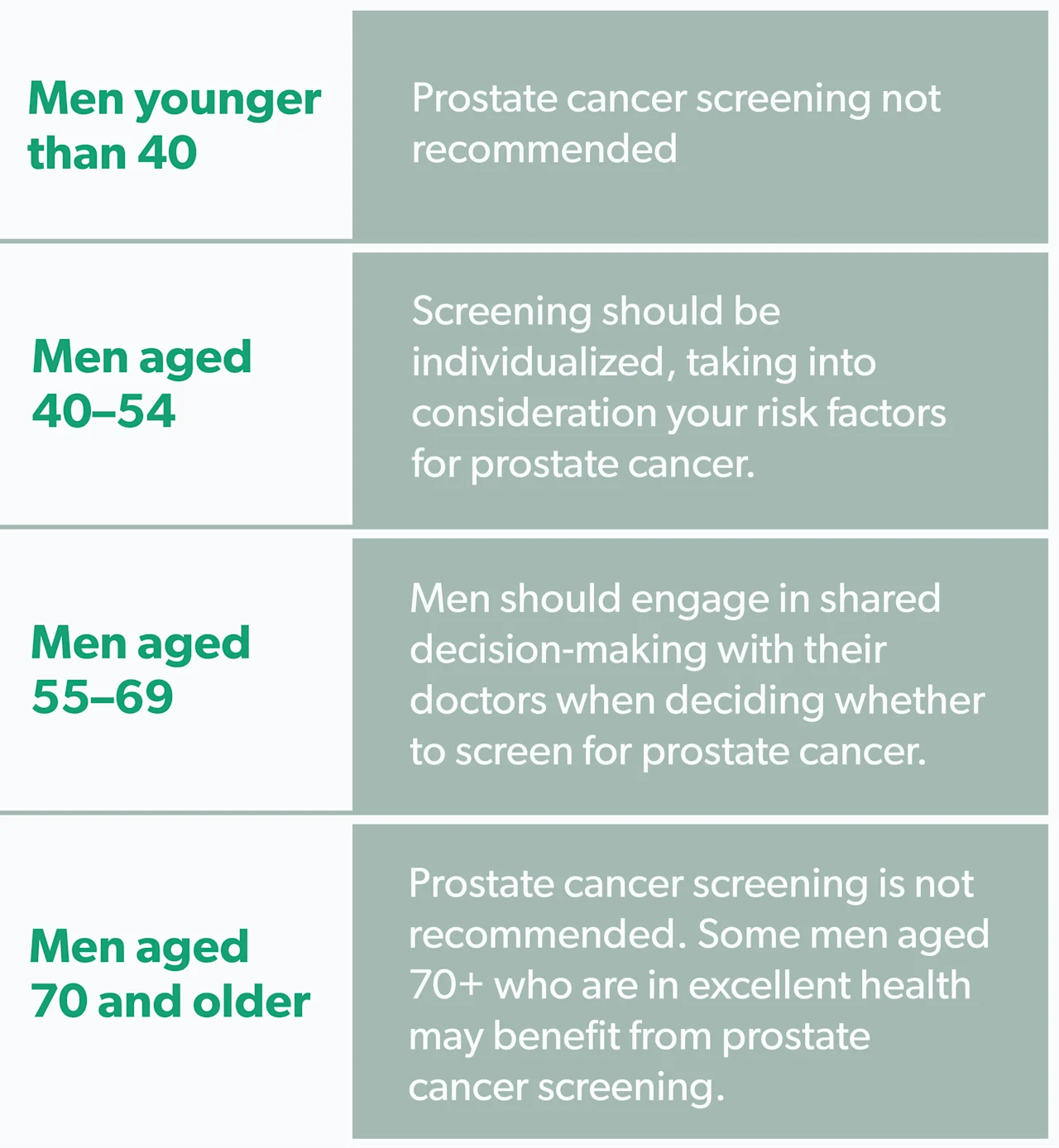

For all of these reasons and more, it’s generally recommended that screening be highly individualized, taking all risk factors into account. Medical organizations offer recommendations around prostate cancer screening with PSAs that differ slightly in some respects.

The American Urological Association (AUA) recommendations are (AUA, 2018):

Men younger than 40

Prostate cancer screening is not recommended

Men aged 40-54

Screening should be individualized, with risk factors for prostate cancer taken into consideration.

Men aged 55-69

Men should engage in shared decision-making with their doctors when deciding whether to screen for prostate cancer.

Men 70 and older

Prostate cancer screening is not recommended. Some men age 70+ years who are in excellent health may benefit from prostate cancer screening.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has recommendations similar to the AUA but doesn’t mention men under age 55 or over age 70+ who are in excellent health (USPSTF, 2018).

The American Academy of Family Practice (AAFP) argues against routine screening because they believe the risks outweigh the benefits. The AAFP is unclear whether healthcare providers should initiate a conversation with patients about screening or only screen if a patient specifically asks (AAFP, 2018).

Knowing if you have any risk factors for prostate cancer can guide lifestyle choices and decisions about screening while honoring your unique set of circumstances. If you do receive a diagnosis, your healthcare provider will work closely with you to decide on the best course of action.

Grades and stages of prostate cancer

If your screening tests are abnormal, your doctor may perform more tests to confirm a prostate cancer diagnosis. These may include an ultrasound, MRI, or biopsy.

Following diagnosis, the grade and stage of cancer are assessed. First off, the grade and stage of a tumor are two distinct things. The grade indicates how quickly the cancer is likely to grow and spread. The stage refers to the size of the cancer and whether it has spread to other parts of the body.

When describing cancer staging, you’ll likely hear the words localized, locally advanced, or metastatic. Here’s what they mean (Leslie, 2021):

Localized: This means the cancer is only in the prostate. It’s in early stages, and hasn’t grown into nearby tissues or distant parts of the body. Localized prostate cancer includes stage 1 and stage 2.

Locally advanced: This means the cancer has grown through the covering of the prostate (called the capsule) to nearby tissue. Locally advanced prostate cancer includes stage 3 and stage 4.

Metastatic: If it’s metastatic prostate cancer, it’s spread beyond the tissues surrounding the prostate to other parts of the body.

Prostate cancer treatment

The earlier prostate cancer is detected, the more effectively it can be treated. In fact, nearly 100% of people diagnosed with localized or regional prostate cancer today will be alive in five years (Leslie, 2021).

But it’s easy to get overwhelmed with the number of prostate cancer treatment options. You and your healthcare provider will need to consider a few things when deciding on the best course of action (or whether to take action at all).

Such considerations include the stage of the tumor, treatment side effects (like erectile dysfunction and bladder control loss), and your age and overall health. Prostate cancer treatment options include (Leslie, 2021):

Watchful waiting: This strategy may be useful in situations where you’re not trying to cure your prostate cancer, like in frail, elderly people, for example. Your goal is to watch for any concerning symptoms and address them as they arise.

Active surveillance and monitoring: Unlike watchful waiting, this strategy is used for early-stage prostate cancer. Over time you’ll get regular physical exams, PSA tests, MRIs, or biopsies to keep an eye on things. Providers start treatment if there is evidence that the cancer is progressing.

Surgery: If the prostate cancer has not spread, you can undergo what’s called a radical prostatectomy. The surgeon removes the entire prostate gland during this procedure, plus some surrounding tissue.

Radiation therapy: There are two different types of radiation therapy for prostate cancer: external beam and brachytherapy radioactive seed placement. These have fewer side effects than surgery and nearly the same survival outcome.

Hormone therapy: Some doctors use hormone therapy to lower the androgen hormone levels in the body to stop them from affecting cancer cells. This is also called androgen deprivation therapy. Hormone therapy is often combined with radiation therapy for better results.

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy is a treatment that uses anti-cancer drugs (like docetaxel) to stop the growth of cancer cells. It can be used alone or with hormone therapy.

Prostate cancer vaccine: Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is a cancer vaccine that stimulates the immune system to attack cancer cells. It’s used to treat certain kinds of advanced prostate cancer, but only improves survival by about one year.

Cryotherapy: Cryotherapy treatment involves freezing and killing cancer cells. Most healthcare providers do not use cryotherapy as the first treatment for prostate cancer. It’s sometimes an option if the cancer has come back after radiation therapy.

While its near-inevitability doesn’t make a prostate cancer diagnosis any less daunting, the sheer number of survivors living full, productive, and long lives tell us that prostate cancer is very treatable and manageable. And when detected in its earlier stages, it’s often completely curable.

Prostate cancer prevention

You can’t change your age, family history, or ethnicity. But there are other risk factors that may affect your chances of developing prostate cancer you can have some control over. There's evidence to suggest that making the following changes may lower your risk of developing prostate cancer (Leslie, 2021; Kaiser, 2019):

Exercising and maintaining a healthy weight

Reducing your consumption of red meat, dairy, and saturated fat

Eating more foods rich in lycopene, like tomato products

Drinking coffee and green tea

Ejaculating more frequently

Taking 5-ɑ reductase inhibitor medications like finasteride (brand name Propecia) or dutasteride

Quitting smoking

Finasteride Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). (2018). Prostate Cancer Screening . Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all-clinical-recommendations/prostate-cancer.html#:~:text=The%20AAFP%20recommends%20against%20screening,potential%20benefit%20screening%20is%20diminished.

American Cancer Society (ACS). (2021). Cancer Statistics Center . Retrieved from https://cancerstatisticscenter.cancer.org/#!/

American Urological Association (AUA). (2018). Early Detection of Prostate Cancer . Retrieved on Nov. 9, 2021 from https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-guideline#x2618

Bhindi, A., Bhindi, B., Kulkarni, G. S., Hamilton, R. J., Toi, A., Van DerKwast, T. H., et al. (2017). Modern-day prostate cancer is not meaningfully associated with lower urinary tract symptoms: analysis of a propensity score-matched cohort. Canadian Urological Association Journal , 11 (1-2), 41–46. doi:10.5489/cuaj.4031. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28443144/

Cui, Z., Liu, D., Liu, C., & Liu, G. (2017). Serum selenium levels and prostate cancer risk: A MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) , 96 (5), e5944. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000005944. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28151881/

Fenton, J. J., Weyrich, M. S., Durbin, S., et al. (2018). Prostate-Specific Antigen–Based Screening for Prostate Cancer: Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA , 319 (18), 1941–1931. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.3712. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29801018/

Fujita, K., Hayashi, T., Matsushita, M., Uemura, M., & Nonomura, N. (2019). Obesity, inflammation, and prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Medicine , 8 (2), 201. doi:10.3390/jcm8020201. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30736371/

Kaiser, A., Haskins, C., Siddiqui, M. M., Hussain, A., & D'Adamo, C. (2019). The evolving role of diet in prostate cancer risk and progression. Current Opinion in Oncology , 31 (3), 222–229. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000519. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7379157/

Leslie, S. W., Soon-Sutton, T. L., Sajjad, H., et al. (2021). Prostate cancer. [Updated 2021 Sep 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Nov. 9, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550/

Naji, L., Randhawa, H., Sohani, Z., Dennis, B., Lautenbach, D., Kavanagh, O., … Profetto, J. (2018). Digital Rectal Examination for Prostate Cancer Screening in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Annals of Family Medicine , 16 (2), 149–154. doi:10.1370/afm.2205. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29531107/

Ng, M., Baradhi, K. M. (2021). Benign prostatic hyperplasia. [Updated 2021 Aug 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Nov. 9, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558920/

Rawla, P. (2019). Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World Journal of Oncology, 10 (2), 63–89. doi:10.14740/wjon1191. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6497009/

Rider, J. R., Wilson, K. M., Sinnott, J. A., Kelly, R. S., Mucci, L. A., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2016). Ejaculation frequency and risk of prostate cancer: updated results with an additional decade of follow-up. European Urology , 70 (6), 974–982. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.03.027. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5040619/ .

Rowles, J. L., Ranard, K. M., Smith, J. W., An, R., & Erdman, J. W. (2017). Increased dietary and circulating lycopene are associated with reduced prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases , 20, 361–377. doi:10.1038/pcan.2017.25. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28440323/

Singh, O., & Bolla, S. R. (2021). Anatomy, abdomen and pelvis, prostate. [Updated 2021 Jul 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved on Nov. 9, 2021 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540987/ .

Wang, G., Zhao, D., Spring, D. J., & DePinho, R. A. (2018). Genetics and biology of prostate cancer. Genes & Development , 32 (17-18), 1105–1140. doi:10.1101/gad.315739.118. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6120714/

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). (2018). Final Recommendation Statement: Prostate Cancer: Screening. Retrieved on Nov. 9, 2021 from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening