Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

You’ve likely heard that stress is bad for you and that you should embrace any activity that will help you de-stress. But is stress always bad? Let’s look at the pros and cons of stress and why it can take such a toll on your health.

What is stress?

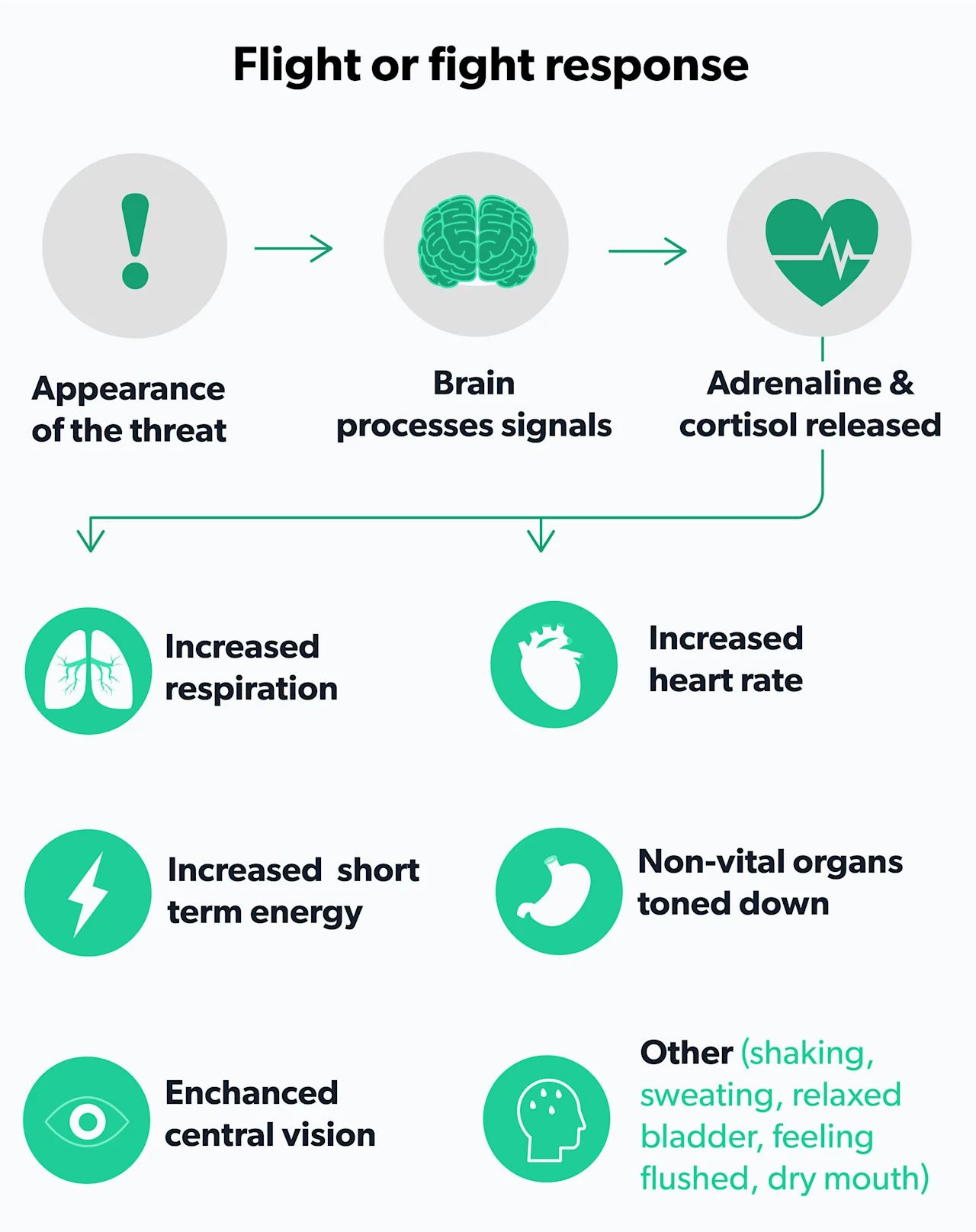

Stress is defined as a mental or emotional strain caused by demanding circumstances. When we think of stress, we usually think of the body’s reaction to a stressor: the racing heartbeat or ‘butterflies in the stomach are parts of the fight-or-flight response designed to help you escape danger. The body’s response usually depends on the perceived threat level and may be mild or extreme. The nervous system automatically responds in the following way (Tank, 2015; Chu, 2020):

The brain’s amygdala (the emotion and behavior center) sends a ‘danger’ message to the hypothalamus—the brain’s command center.

The hypothalamus signals the body’s adrenal glands located on top of both kidneys to release stress hormones, including adrenaline (epinephrine) and cortisol.

Stress hormones trigger the following:

Rapid heart rate and heavy breathing to get blood and oxygen to muscles

Increased glucose levels (inhibiting insulin) to supply the body energy

Eye dilation to improve vision

Muscle contraction to stimulate perspiration

Blood is diverted away from places like the stomach to send to the muscles.

The immune system gets a quick boost.

The brain is focused on the threat at hand, making it temporarily more challenging to remember things.

The stress response allows you to perform more strenuous activity than usual by redirecting the body’s resources to react quickly. After the threat goes away, the system is designed to return to pre-stress levels (Chu, 2020).

Is stress good?

Stress ultimately can be good, tolerable, or toxic. A stress response is good if you’re in a situation that requires a quick physical response. Some stress can also give you a burst of energy and focus to complete a task or perform well. Sometimes, it can even boost the immune system temporarily. That said, if the stress response is triggered frequently, it can wear the system down. (Dhabhar, 2014; McEwan, 2017).

Types of stress

If you’re experiencing stress, it’s helpful to consider what your stress level is. Many health professionals refer to three categories of stress:

Acute stress

Acute stress is what’s most commonly associated with the fight-or-flight response. A rush of stress hormones allows peak performance to escape or act. Adrenaline may make it possible for someone to lift a car to help an injured friend. It allows you to escape being hit by a bus. Milder acute stress may help you catch a bus if you’re late. The body returns to pre-arousal levels with no bad health effects (Chu, 2020).

Episodic acute stress

Real or perceived threats can create a cycle of stress that begins to wear the body down. Episodic acute stress occurs when the stress response is triggered frequently. Taking on too many tasks and ceaseless worrying is an example. This is considered more damaging to the body, as cortisol and other stress hormones are present often. This may be tolerable depending on how well a person copes with stress (Boys Town, 2021; McEwan, 2017).

Chronic stress

In cases of chronic stress, a person is in a constant state of stress. Some may not even realize it and become used to the feelings of long-term stress. This is the most toxic form of stress, as stress hormones never really leave the system. This can lead to burnout and increase the risk for a range of illnesses if left unchecked (Hammen, 2009; Dhabhar, 2014; Lupien, 2018).

Effects of chronic stress

The effects of stress can range from minor temporary symptoms to serious and chronic health problems. In cases of episodic acute stress, the body continues to secrete stress hormones at different times, which can lead to poor concentration, irritability, and frustration.

With chronic stress, the body adapts to cope with higher stress levels, but it takes a toll. Those with chronic stress may notice changes in how they perceive or remember things, find it harder to deal with stressful situations, suffer from fatigue, are at increased risk for developing an anxiety disorder or depression, and illnesses like heart disease (Ketchesin, 2017; Tsigos, 2020; Yaribeygi, 2017; McEwan, 2017).

Stress and the brain

Stress can help encode some memories, especially those related to strong emotions, but it makes it harder to retrieve memories like a friend’s name (Shields, 2018; Vogel, 2016).

Studies show chronic stress reduces the size of the hippocampus and negatively impacts memory and learning (Kim, 2015; Mariotti, 2015). At the same time, stress boosts activity in the amygdala, a brain area that deals with fear, emotion, and behavior (Zhang, 2018). Some studies have also found that stress is linked to an increased risk for dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease (Justice, 2018).

Stress and the heart

During the stress response, arteries narrow to divert blood to muscles. Over time, chronic stress can lead to high blood pressure and boosts the risk of heart attack and stroke (Mariotti, 2015; Steptoe, 2012).

Stress, digestion, and metabolism

The stress response prompts the liver to produce extra blood sugar (glucose). Higher levels of glucose over time increase the risk for type 2 diabetes (Sharma, 2020).

Stress also affects the way food moves through the body, leading to diarrhea or constipation. Long-term stress is linked to a variety of gastrointestinal problems, including irritable bowel syndrome (Konturek, 2011). Research has also linked stress with food cravings and eating disorders (Razzoli, 2017).

Stress and the immune system

In the very short term, stress has been shown to help the body avoid infections and heal wounds (Dhabhar, 2014). However, over time stress hormones dampen the immune system, making those with chronic stress more likely to get infections. A dampened immune system also increases the risk of cancer (Morey, 2015; Sakhnevych, 2018).

Stress, muscles, and bones

Stress affects the entire musculoskeletal system by tensing up muscles. It’s a way of guarding against pain and injury, but the result is muscle tension that can cause headaches, backaches, and body aches. Some may then reach for pain medications or stop exercising (Chu, 2020). Cortisol has been shown to reduce bone mineral density (Suarez-Bregua, 2018).

Stress and sex

During a stress response, the body’s resources are diverted away from the reproductive system. If stress becomes chronic, it can reduce sexual desire and negatively impact sperm production, sperm maturation, menstruation, and pregnancy (Chu, 2020; Tsigos, 2020; Kalantaridou, 2010). When stress is chronic, the release of cortisol over time can also impede the production of testosterone, which in turn can then lead to ED (Rivas, 2014).

Symptoms of stress

Symptoms of stress can vary. Some causes of stress, like being late or dealing with work projects, may be relatively minor and part of daily life. They may prompt various symptoms like tension headaches that can make life difficult and worsen existing health conditions like heart disease and asthma. But acute stress symptoms typically go away once the stressor is gone (Chu, 2020; Oren, 2020).

With chronic stress, symptoms often linger. Stressful living conditions or life events like a divorce, job loss, the death of a family member, or other sources of stress that threaten a person’s well-being can trigger chronic stress. Health professionals report a range of physical, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms linked to stress. These can be temporary or chronic if the stress continues (Adamsson, 2018; Chu, 2020, AIS, 2020; Schneiderman, 2005):

Physical symptoms

Aches/pains

Nausea/dizziness

Gastrointestinal problems

Rapid heartbeats/chest pain

Frequent ailments like colds or flu

Loss of sex drive

Fatigue

Other physical changes

Cognitive changes

Anxious/racing thoughts

Excessive worrying

Negative thinking

Poor judgment

Memory difficulties

Concentration problems

Emotional changes

Anxiety

Agitation/irritability

Anger

Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

Moodiness

Unhappiness

Depression

Loneliness/isolation

Other emotional problems

Behavioral changes

Changes in eating patterns

Changes in sleep patterns

Nervous habits (nail-biting, etc.)

Procrastination

Neglecting job/responsibilities

Social withdrawal

Use of alcohol or drugs to relax

Diagnosing stress

It’s important to contact a healthcare provider if you feel stress is negatively affecting your life. The goal is to intervene with the right management approaches.

There’s not a specific test for stress. So, healthcare providers discuss symptoms, stressors, lifestyle, and family history. A questionnaire can help identify stress levels and anxiety or depression, which can have similar symptoms. Blood and urine samples may help rule out other medical conditions. For example, thyroid disease is linked to anxiety and depression (Bathla, 2016; Itterman, 2015).

Many problems and situations can make a person feel threatened or challenged. The American Psychological Association (APA) has consistently found work a significant source of stress in its annual Stress in America survey (APA, 2018). Overall, a stressor can range from mild and temporary to life-altering, such as the death of a loved one. There is evidence that past trauma can make it harder to cope with stress and that intervening early after a stressful event may lessen long-term impacts (McEwan, 2017; Lupien, 2018).

The National Institute of Mental Health supports using the Stress and Adversity Inventor (STRAIN) online survey to help assess the cumulative exposure to life stress. There is an adult and adolescent version (Slavitch, 2018). While online tools should not replace the advice of a healthcare provider, they can help you develop questions to ask.

Managing and preventing stress

A lot of times, stress goes away once a stressful period has passed. Other times advice from a healthcare provider is needed. If other medical or mental conditions are ruled out, managing stress typically begins with a look at lifestyle factors and stress management techniques.

Lifestyle factors

Stress experts have identified various lifestyle approaches that boost resilience to stress (McEwan, 2017):

Exercise regularly; regular exercise reduces cortisol levels (Beserra, 2018).

Improve quantity and quality of sleep.

Improve social support networks.

Maintain a healthy diet.

Avoid smoking/drugs.

Problem-focused coping

Do you have some control over the stressors in your life? If so, a problem-focused coping style may be advised. This involves taking action to change the circumstance. It may be checking off a to-do list or booking a therapy appointment. You can combine this with an emotion-focused approach (APA, 2020a).

Emotion-focused coping

Often we have no control over a stressful situation. This is when it’s helpful to use emotion-focused coping. The goal of this approach is to react in a more positive way to a stressor (APA, 2020b). There are a variety of methods that can be helpful, such as:

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): CBT is talk therapy that helps you recognize and react differently to situations that create stress or anxiety (Chand, 2021).

Mindfulness-based intervention programs: These are techniques that aim to change how we react and add relaxation and mindfulness, which are shown to reduce stress. Among the evidence-based programs are Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Relaxation Response Resiliency Program (Worthen, 2020; Park, 2013).

Meditation and moving meditation: Studies have shown meditation and ‘moving meditations’ like yoga, Tai Chi, and Qi Gong can reduce stress levels (Pascoe, 2017; Maddux, 2018; Zheng, 2018; Wang, 2014).

Biofeedback: This intervention involves patients using equipment to track and control their physiological responses. It’s been shown to reduce symptoms of stress, anxiety, depression, and other health conditions (Ratanasiripong, 2015).

Relaxation techniques, gadgets, and apps: There are a variety of techniques and tools that may offer ways to de-stress. Most are not evidence-based but may help you relax while improving your mood and feelings of wellness.

You can’t eliminate stress, and not all stress is bad. Some manageable stress can be helpful and even boost performance and learning (Rudland, 2020). There’s an entire field of study that focuses on good stress, known as eustress.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) offers stress tips and a suicide prevention hotline for those who may feel overwhelmed and need immediate guidance regarding mental health.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

References

Adamsson, A., & Bernhardsson, S. (2018). Symptoms that may be stress-related and lead to exhaustion disorder: a retrospective medical chart review in Swedish primary care. BMC Family Practice, 19 (1). doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0858-7. Retrieved from https://bmcfampract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12875-018-0858-7

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Emotion-focused coping. APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/emotion-focused-coping

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Problem-focused coping. APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/problem-focused-coping

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Coping with stress at work. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/healthy-workplaces/work-stress

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stress in America Press Room. American Psychological Association . Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/

Bathla, M., Singh, M., & Relan, P. (2016). Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among patients with hypothyroidism. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 20 (4), doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.183476. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4911835/

Beserra, A. H., Kameda, P., Deslandes, A. C., Schuch, F. B., Laks, J., & Moraes, H. S. (2018). Can physical exercise modulate cortisol level in subjects with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 40 (4), 360–368. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2017-0155. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30570106/

Chand, S. P. (2021). Cognitive behavior therapy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470241/

Chu, B. (2020). Physiology, stress reaction. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/

Dhabhar, F. S. (2014). Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunologic Research, 58 (2-3), 193–210. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24798553/

Hammen, C., Kim, E. Y., Eberhart, N. K., & Brennan, P. A. (2009). Chronic and acute stress and the prediction of major depression in women. Depression and Anxiety, 26 (8), 718–723. doi: 10.1002/da.20571. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19496077/

Ittermann, T., Völzke, H., Baumeister, S. E., Appel, K., & Grabe, H. J. (2015). Diagnosed thyroid disorders are associated with depression and anxiety. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50 (9), 1417–1425. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1043-0. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25777685/

Justice N. J. (2018). The relationship between stress and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of Stress, 8, 127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2018.04.002. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5991350/

Kalantaridou, S. N., Zoumakis, E., Makrigiannakis, A., Lavasidis, L. G., Vrekoussis, T., & Chrousos, G. P. (2010). Corticotropin-releasing hormone, stress and human reproduction: an update. Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 85 (1), 33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.02.005. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20412987/

Ketchesin, K. D., Stinnett, G. S., & Seasholtz, A. F. (2017). Corticotropin-releasing hormone-binding protein and stress: from invertebrates to humans. Stress, 20 (5), 449–464. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2017.1322575. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28436309/

Kim, E. J., Pellman, B., & Kim, J. J. (2015). Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learning & Memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.), 22 (9), 411–416. doi: 10.1101/lm.037291.114. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4561403/

Konturek, P. C., Brzozowski, T., & Konturek, S. J. (2011). Stress and the gut: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, diagnostic approach and treatment options. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology: An Official Journal of the Polish Physiological Society, 62 (6), 591–599. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22314561/

Lupien, S. J., Juster, R.-P., Raymond, C., & Marin, M.-F. (2018). The effects of chronic stress on the human brain: From neurotoxicity, to vulnerability, to opportunity. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 49, 91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.02.001. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29421159/

Maddux, R. E., Daukantaité, D., & Tellhed, U. (2017). The effects of yoga on stress and psychological health among employees: an 8- and 16-week intervention study. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31 (2), 121–134. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2017.1405261. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29166771/

Mariotti, A. (2015). The effects of chronic stress on health: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain–body communication. Future Science OA, 1 (3). doi: 10.4155/fso.15.21. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28031896/

McEwen, B. S. (2017). Neurobiological and systemic effects of chronic stress. Chronic Stress, 1, 247054701769232. doi: 10.1177/2470547017692328. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28856337/

Morey, J. N., Boggero, I. A., Scott, A. B., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2015). Current directions in stress and human immune function. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.007. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4465119/

Oren, E., & Martinez, F. D. (2020). Stress and asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, 125 (4). doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.022. Retrieved from https://www.annallergy.org/article/S1081-1206(20)30511-1/fulltext

Park, E. R., Traeger, L., Vranceanu, A.-M., Scult, M., Lerner, J. A., Benson, H., Denninger, J., & Fricchione, G. L. (2013). The development of a patient-centered program based on the relaxation response: The Relaxation Response Resiliency Program (3RP). Psychosomatics, 54 (2), 165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2012.09.001. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23352048/

Pascoe, M. C., Thompson, D. R., Jenkins, Z. M., & Ski, C. F. (2017). Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 95, 156–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.004. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28863392/

Ratanasiripong, P., Kaewboonchoo, O., Ratanasiripong, N., Hanklang, S., & Chumchai, P. (2015). Biofeedback intervention for stress, anxiety, and depression among graduate students in public health nursing. Nursing Research and Practice, 2015, 1–5. doi: 10.1155/2015/160746. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25954515/

Razzoli, M., Pearson, C., Crow, S., & Bartolomucci, A. (2017). Stress, overeating, and obesity: Insights from human studies and preclinical models. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 76, 154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.026. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28292531/

Rivas AM, Mulkey Z, Lado-Abeal J, Yarbrough S. (2014). Diagnosing and managing low serum testosterone. Proctology (Baylor University Medical Center); 27 (4):321-324. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2014.11929145. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4255853/

Sakhnevych, S. S., Yasinska, I. M., Bratt, A. M., Benlaouer, O., Gonçalves Silva, I., Hussain, R., et al. (2018). Cortisol facilitates the immune escape of human acute myeloid leukemia cells by inducing latrophilin 1 expression. Cellular & Molecular Immunology, 15 (11), 994–997. doi: 10.1038/s41423-018-0053-8. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29907881/

Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., & Siegel, S. D. (2005). Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1 (1), 607–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17716101/

Sharma, V. K., & Singh, T. G. (2020). Chronic stress and diabetes mellitus: Interwoven pathologies. Current Diabetes Reviews, 16 (6), 546–556. doi: 10.2174/1573399815666191111152248. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31713487/

Shields, G. S., Sazma, M. A., McCullough, A. M., & Yonelinas, A. P. (2017). The effects of acute stress on episodic memory: A meta-analysis and integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143 (6), 636–675. doi: 10.1037/bul0000100. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28368148/

Slavich, G. M., & Shields, G. S. (2018). Assessing lifetime stress exposure using the stress and adversity inventory for adults (adult STRAIN): An overview and initial validation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80 (1), 17–27. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000534. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29016550/

Steptoe, A., & Kivimäki, M. (2012). Stress and cardiovascular disease. Nature Reviews Cardiology, 9 (6), 360–370. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.45. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22473079/

Boys Town National Research Hospital. (n.d.). Stress. Retrieved from https://www.boystownhospital.org/knowledge-center/stress

Suarez-Bregua, P., Guerreiro, P. M., & Rotllant, J. (2018). Stress, glucocorticoids and bone: A review from mammals and fish. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 9. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00526. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6139303/

The American Institute of Stress. (2020). Stress effects. Retrieved from https://www.stress.org/stress-effects

Tsigos, C. (2020). Stress: endocrine physiology and pathophysiology. In: Endotext [Internet]. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK278995/

UCLA Laboratory for Stress Assessment and Research. (n.d.). Stress and Adversity Inventory (STRAIN). Retrieved from https://www.uclastresslab.org/projects/strain-stress-and-adversity-inventory/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). 5 things you should know about stress. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/stress/

Vogel, S., & Schwabe, L. (2016). Learning and memory under stress: implications for the classroom. NPJ Science of Learning, 1 (1). doi: 10.1038/npjscilearn.2016.11. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/npjscilearn201611

Wang, C.W., Chan, C.H.Y., Ho, R.T.H., Chan, J.S.M., Ng, S.M., & Chan, C.L.W. (2014). Managing stress and anxiety through qigong exercise in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 14 (1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-8 Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24400778/

William Tank, A., & Lee Wong, D. (2014). Peripheral and central effects of circulating catecholamines. Comprehensive Physiology, 1–15. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140007. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25589262/

Yaribeygi, H., Panahi, Y., Sahraei, H., Johnston, T. P., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI Journal, 16, 1057–1072. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-480. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5579396/

Zhang, X., Ge, T. tong, Yin, G., Cui, R., Zhao, G., & Yang, W. (2018). Stress-induced functional alterations in amygdala: Implications for neuropsychiatric diseases. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00367. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29896088/

Zheng, S., Kim, C., Lal, S., Meier, P., Sibbritt, D., & Zaslawski, C. (2017). The effects of twelve weeks of Tai Chi practice on anxiety in stressed but healthy people compared to exercise and wait-list groups-A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74 (1), 83–92. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22482. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28608523/