Key takeaways

Safe, sustainable weight loss tends to happen at about 1–2 pounds per week, which means visible changes often become clearer over 1–3 months, depending on your starting weight.

You may notice early changes in your energy levels, mood, or how clothes fit before the number on the scale shifts dramatically.

The timeline for how long it takes to see weight loss results depends on things like metabolism, body composition, activity level, medications, and whether you’re in a calorie deficit.

Slow and steady progress is more likely to support fat loss, improve overall health markers, and tends to be easier to maintain long-term than with rapid weight loss.

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Key takeaways

Safe, sustainable weight loss tends to happen at about 1–2 pounds per week, which means visible changes often become clearer over 1–3 months, depending on your starting weight.

You may notice early changes in your energy levels, mood, or how clothes fit before the number on the scale shifts dramatically.

The timeline for how long it takes to see weight loss results depends on things like metabolism, body composition, activity level, medications, and whether you’re in a calorie deficit.

Slow and steady progress is more likely to support fat loss, improve overall health markers, and tends to be easier to maintain long-term than with rapid weight loss.

You might be adjusting how you eat, move, or support your health on a weight loss journey and hoping to see signs of progress quickly. But how long does it take to notice weight loss, really? There is a general timeline, but visible changes can vary from person to person.

Some notice small changes within a couple of weeks. For others, it may take a month or more. That’s because the speed of weight loss and the point at which it becomes visible in each individual depend on a mix of biological, lifestyle, and environmental factors.

Understanding what to expect can make the process feel clearer and less confusing, so let’s look at what the research says.

How long does it take to notice weight loss?

There isn’t one exact timeline, because weight change and visible change don’t always happen at the same pace.

A review found that adults participating in short-term nutrition and physical activity programs (13 weeks or less) lost an average of 2.7 kilograms (around 6 pounds) more than non-participants. Many people losing a modest amount of weight like this may notice other signs of success before major scale changes, such as:

More stable energy levels

Improvements in sleep or mood

Clothes fitting differently

Movement feeling easier

If you’re using a weight loss medication like Ozempic or Wegovy, the timeline can speed up but will still vary from person to person. In real-world research of adults using semaglutide with lifestyle changes, people lost an average of 6% of their starting weight by 3 months, with many seeing noticeable changes earlier. By 6 months, average weight loss reached around 11%.

What is a realistic weight loss timeline?

A realistic and sustainable weight loss timeline usually involves losing about 1–2 pounds per week. This rate is supported by clinical guidelines because it helps preserve muscle mass, supports your metabolism, and is more likely to lead to long-term results compared to losing weight very quickly.

Research also suggests that losing around 5% of your starting body weight is where physical changes and health improvements often become noticeable. Here are some examples of what 5% looks like (and how long it takes) for different starting weights:

Starting Weight | 5% Weight Loss | Approximate Time to Reach (at 1–2 lbs/week) |

|---|---|---|

150 lbs | ~7.5 lbs | ~4–8 weeks |

200 lbs | ~10 lbs | ~5–10 weeks |

250 lbs | ~12.5 lbs | ~6–12 weeks |

300 lbs | ~15 lbs | ~7–15 weeks |

It’s important to note that weight loss isn’t linear. Hydration, underlying conditions, and medications can all lead to normal weight fluctuations that can temporarily mask progress on the scale and affect when you start noticing weight loss.

This is why tracking multiple progress indicators — like how you feel or how clothes fit — can give a clearer picture of the changes taking place.

Stages of losing weight

There aren’t universal stages of weight loss, because everyone’s body responds differently. Many people experience a general pattern that can be broken into three primary stages as their body adapts to changes in diet and activity levels.

Here’s a breakdown of these stages of losing weight over time:

Stage 1: During the first few days or weeks, you may notice relatively rapid weight loss. These early changes are often from reduced water weight and bloating, especially if you’re eating fewer salty or ultra-processed foods.

Stage 2: Over the next few months, weight loss may slow down as your metabolism adapts. This can feel like a plateau but you’re likely losing more fat at this stage, which is a good thing. Visible changes may be subtle, but you may notice improvements in energy, digestion, or movement.

Stage 3: After 6–12 months, you’ll enter the weight maintenance phase, where your primary goal is to prevent weight regain. You may still lose some weight slowly over time, but the goal for most people at this stage is to keep off the weight they’ve lost.

Factors that affect how quickly you lose weight

There are many reasons why weight loss happens faster for some people than others. These factors influence how your body uses and stores energy, your appetite, and even how visible changes appear over time. These factors include:

Body composition: People with a higher starting weight or a greater percentage of body fat may notice changes on the scale sooner than someone with a lower starting weight or more muscle mass (which can affect how many calories you burn at rest). However, it may take a little longer for changes to be visible to the naked eye in people with more weight to lose.

Calorie intake and consistency: Restricting calories (typically by 500-750 calories per day) is one of the core drivers of weight loss. Frequent fluctuations (for example, eating very low one day and higher the next) can make progress harder to see and track.

Total daily energy expenditure (TDEE): Your TDEE is based on your metabolism, daily movement, and exercise. Two people eating the same amount may lose weight at different rates if their TDEE measurements differ.

Physical activity level: Movement affects weight loss both directly (by burning calories) and indirectly (by improving your mood, sleep, and appetite regulation). Small increases in daily movement — like walking more or standing instead of sitting — can meaningfully support progress.

Sleep quality: Studies show that not getting enough sleep can increase hunger hormones (like ghrelin) and decrease fullness hormones (like leptin), which can make weight loss more challenging. Poor sleep can also affect energy levels and motivation to move.

Stress levels: High stress can trigger cortisol changes that influence appetite, cravings, and how the body stores fat. Long-term stress can also make it harder to maintain routines that support weight loss.

Medications and medical conditions: Certain conditions (like Cushing’s syndrome or polycystic ovary syndrome, aka PCOS) and some medications can affect metabolism, appetite, or fluid retention, all of which can contribute to weight fluctuations. Some conditions can also affect how well medications work to support weight loss. For example, research shows that people with type 2 diabetes using semaglutide lose about 4% of their starting weight by 3 months, compared with 6% in those without diabetes in the same timeframe.

Hormonal changes: Hormones related to your menstrual cycle, perimenopause, or menopause can influence fluid balance, appetite, and fat distribution. This can temporarily mask or slow visible progress, even when you’re doing everything consistently.

Nutrition quality: Weight loss isn’t only about calories; what you eat matters too. Higher protein and fiber intake can support fullness, stable blood sugar, and lean muscle maintenance, all of which can influence how quickly you notice changes.

Hydration and sodium intake: Water retention can fluctuate based on hydration level, salt intake, exercise, or menstrual cycle. These daily shifts can temporarily hide fat loss on the scale.

Fat loss vs. weight loss: what’s the difference?

Though the terms are often used interchangeably, fat loss and weight loss are not the same. Weight loss is a decrease in overall body weight, whereas fat loss refers specifically to reducing stored body fat. Fat loss is what most people mean when they say they want to “lose weight,” especially if the goal is improved health or changes in how their body looks and feels.

More specifically:

Weight loss: This reflects changes in total body weight and can include shifts in fat, muscle, water, glycogen (stored carbohydrates), and digestive contents. Because many of these factors fluctuate from day to day, the scale can move up or down even when true fat loss hasn’t occurred.

Fat loss: This refers to a reduction in adipose (fat) tissue. Fat loss is typically associated with improvements in metabolic health, body composition, and long-term weight maintenance. It tends to happen more gradually than changes in water weight or digestion, which is why visible progress often takes several weeks to enter the scene.

Risks of rapid weight loss

Losing weight quickly isn’t necessarily better, and in many cases, it can come with downsides. Some potential risks of rapid weight loss include:

Muscle loss: When weight drops too quickly, your body breaks down muscle for energy. Studies also show that losing muscle can lower your resting metabolic rate, which makes it more difficult to lose weight and easier to regain it.

Nutrient deficiencies: Very low-calorie diets can make it difficult to get enough essential nutrients like protein, iron, calcium, and certain vitamins. Over time, this can affect energy levels, bone health, metabolism, and immune function.

Slower metabolism: Aggressive calorie restriction can cause the body to conserve energy by lowering metabolic rate. This can make continued weight loss more difficult and may contribute to weight regain once regular eating resumes.

Hormonal disruptions: Rapid weight loss can impact appetite-regulating hormones, including ghrelin and leptin, which influence hunger and fullness. This may lead to increased cravings and difficulty maintaining eating patterns.

Fatigue: Severe calorie restriction can make exercise and daily tasks feel harder, which may reduce activity levels and further slow progress.

5 tips for healthy, safe weight loss

Healthy weight loss is most sustainable when it comes from steady, realistic habits that you can maintain over time. The focus is on progress, not perfection. Focus on habits like:

Maintaining a consistent calorie deficit: Consistently restricting your calories (within a safe range) helps with slow and steady weight loss.

Including protein at most meals: Protein preserves your muscles and helps you feel full for longer, which is why experts recommend eating 0.8 to 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day.

Moving often and prioritizing strength training: Movement doesn’t have to be formal exercise. Walking more, taking stretch breaks, or standing instead of sitting can meaningfully increase total daily energy burn. In addition to just moving more, resistance training helps preserve or build muscle, which supports metabolism and contributes to visible changes in body composition.

Prioritizing fiber-rich foods: Foods like vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains help support stable energy and digestion. Fiber slows digestion and can help reduce cravings and overeating.

Tracking more than the scale: Since weight can fluctuate day to day, progress often shows up first in how clothes fit, energy, or how movement feels. Paying attention to these signs can offer a clearer picture of what’s changing.

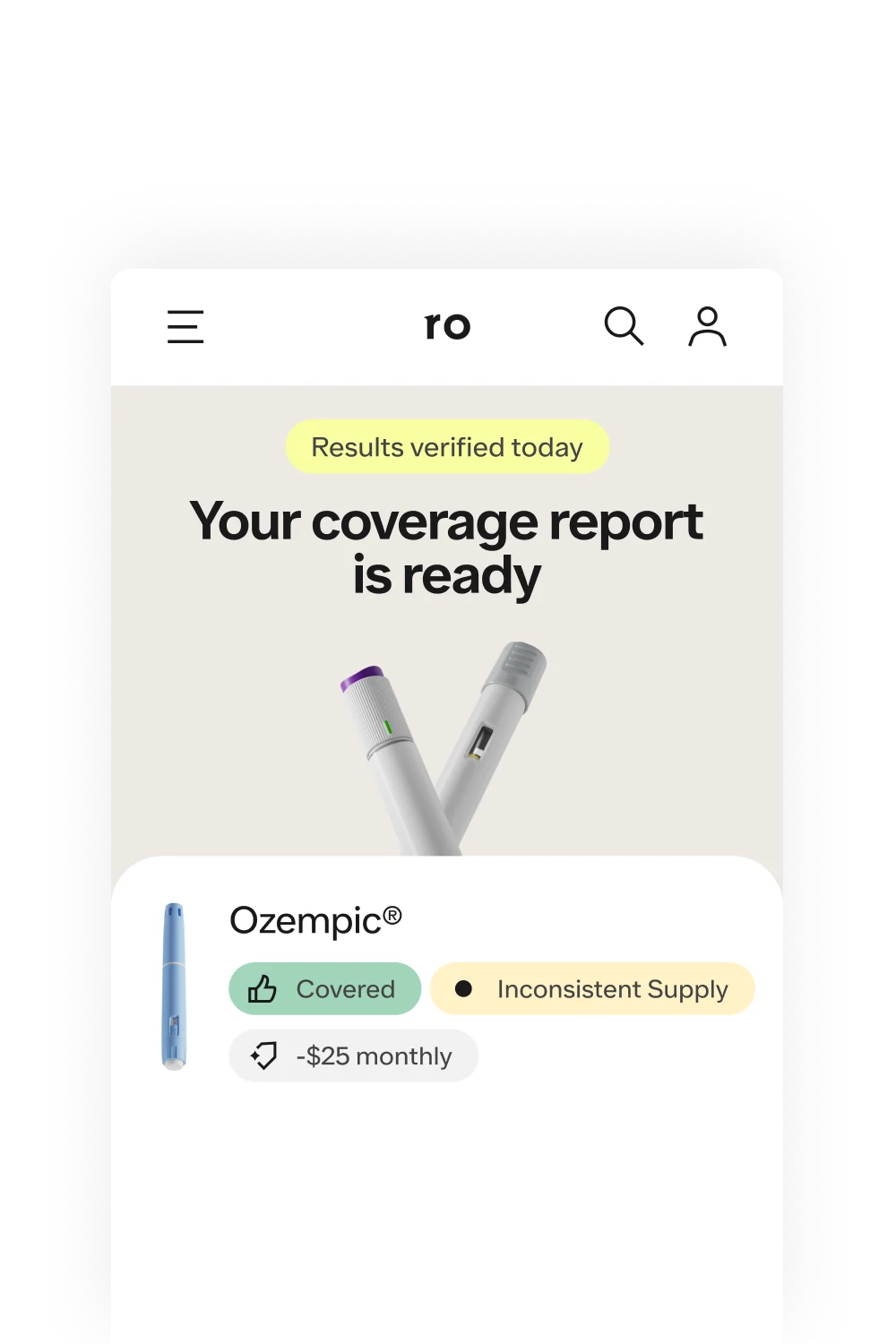

Rx weight loss with Ro

Get access to prescription weight loss medication online

Bottom line

Weight loss progress often becomes noticeable after several weeks, but the exact timeline varies from person to person. Here’s what to keep in mind:

Most people begin to notice changes around 4–6 weeks, with clearer visible differences often emerging by 8–12 weeks. Your starting point, daily habits, and overall health all play roles in how quickly changes show up.

A safe, sustainable rate of weight loss is about 1–2 pounds per week.

Losing around 5% of your starting body weight is often where both physical and metabolic benefits become noticeable.

Progress may show up in energy, sleep, mood, and how clothes fit before the scale reflects major changes.

Consistency with sustainable nutrition, movement, sleep, and stress management habits make a bigger difference in the long run than perfect habits that can’t be sustained.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

What is the hardest stage of weight loss?

The hardest stage of weight loss depends on your unique journey. That said, many people find plateaus challenging. This is when progress slows even though you’re still doing the same things. Small adjustments to movement, protein intake, stress, or sleep can often help progress resume.

Where do you notice weight loss first?

This varies by person, but common early areas include the midsection, hips, and thighs. Genetics and biological sex influence where your body tends to store and lose fat first, so there’s no single pattern that applies to everyone.

Which body part loses fat first?

There’s no way to target fat loss to specific body parts. Your body determines where fat is lost based on factors like genetics and biological sex.

How much weight to lose before you notice?

Many people begin to notice changes after losing around 5% of their starting body weight. This may show up more noticeably in how clothes fit, energy levels, or measurements than on the scale alone.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

Ozempic Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

Wegovy Important Safety Information: Read more about serious warnings and safety info.

References

Alyafei, A., Balfour, J., & Keyes, D. (2025). Physical activity and weight loss maintenance. StatPearls. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572051/

Bhutani, S., Kahn, E., Tasali, E., & Schoeller, D. A. (2017). Composition of two-week change in body weight under unrestricted free-living conditions. Physiological Reports, 5(13), e13336. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13336. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5506524/

Contreras, F., Al-Najim, W., & le Roux, C. W. (2024). Health benefits beyond the scale: the role of diet and nutrition during weight loss programmes. Nutrients, 16(21), 3585. doi: 10.3390/nu16213585. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/16/21/3585

Erdélyi, A., Pálfi, E., Tűű, L., et al. (2023). The importance of nutrition in menopause and perimenopause-a review. Nutrients, 16(1), 27. doi: 10.3390/nu16010027. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10780928/

Farrell, E., Nadglowski, J., Hollmann, E., et al. (2024). Patient perceptions of success in obesity treatment: An IMI2 SOPHIA study. Obesity Science & Practice, 10(4), e70001. doi: 10.1002/osp4.70001. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11329797/

Ghusn, W., De la Rosa, A., Sacoto, D., et al. (2022). Weight loss outcomes associated with semaglutide treatment for patients with overweight or obesity. JAMA Network Open, 5(9), e2231982. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.31982. Retrieved from https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2796491

Giersch, G. E. W., Charkoudian, N., Morrissey, M. C., et al. (2021). Estrogen to progesterone ratio and fluid regulatory responses to varying degrees and methods of dehydration. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 722305. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2021.722305. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sports-and-active-living/articles/10.3389/fspor.2021.722305/full

Guarneiri, L. L., Kirkpatrick, C. F., & Maki, K. C. (2025). Protein, fiber, and exercise: a narrative review of their roles in weight management and cardiometabolic health. Lipids in Health and Disease, 24(1), 237. doi: 10.1186/s12944-025-02659-7. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40652221/

Jaime, K. & Mank, V. (2024). Risks associated with excessive weight loss. StatPearls. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603752/

Kim, J. Y. (2021). Optimal diet strategies for weight loss and weight loss maintenance. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome, 30(1), 20–31. doi: 10.7570/jomes20065. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8017325/

Li, X. & Qi, L. (2019). Gene-environment interactions on body fat distribution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(15), 3690. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153690. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6696304/

Medline Plus. (2025). Weight control. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/weightcontrol.html

Papatriantafyllou, E., Efthymiou, D., Zoumbaneas, E., et al. (2022). Sleep deprivation: effects on weight loss and weight loss maintenance. Nutrients, 14(8), 1549. doi: 10.3390/nu14081549. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9031614/

Rotunda, W., Rains, C., Jacobs, S. R., et al. (2024). Weight loss in short-term interventions for physical activity and nutrition among adults with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Preventing Chronic Disease, 21, E21. doi: 10.5888/pcd21.230347. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2024/23_0347.htm

Ryan, D. H. & Yockey, S. R. (2017). Weight loss and improvement in comorbidity: differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and over. Current Obesity Reports, 6(2), 187–194. doi: 10.1007/s13679-017-0262-y. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5497590/

Sarwan, G., Daley, S. F., Rehman, A. (2024). Management of weight loss plateau. StatPearls. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576400/

Tomiyama, A. J. (2019). Stress and obesity. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 703–718. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102936. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29927688/

Willoughby, D., Hewlings, S., & Kalman, D. (2018). Body composition changes in weight loss: strategies and supplementation for maintaining lean body mass, a brief review. Nutrients, 10(12), 1876. doi: 10.3390/nu10121876. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6315740/