Here's what we'll cover

Here's what we'll cover

Your heart rate—the number of times your heart beats per minute (bpm)—is a key to burning fat and losing weight.

When the rate gets high enough and is in a “fat-burning” zone, your body shifts from using carbs as its primary energy source to using body fat stores instead. So, if you’re on a weight loss journey, finding your target heart rate to burn fat may help you achieve a healthy weight faster.

This article breaks down how to calculate your target heart rate for exercise and highlights physical activities to keep you in the fat-burning zone and on the path to achieving your weight-loss goals.

Calculating your target heart rate for fat loss

Everyone has a resting heart rate (RHR), which is the number of times your heart beats per minute while you’re resting. The average adult’s RHR is 60–-100 bpm, but it may be as low as 40 for athletes (AHA, 2015).

It can be affected by several factors, including stress, hormones, anxiety, medication, and physical activity. A higher RHR is associated with an increased risk of heart disease and a lower life expectancy (Ó Hartaigh, 2014; AHA, 2015).

Figuring out your heart rate is as simple as counting your pulse for 15 seconds and multiplying that number by four. For example, if you count 25 pulses in 15 seconds and multiply that by 4, your heart rate is 100 bpm. The best places to find your pulse include:

Inside the wrist

Side of the neck

Top of the foot

Inside the elbow

Once you find that number, you’ll be able to figure out your fat-burning heart rate zone. But, before you commit to reaching that number with a new exercise routine, talk with a healthcare provider if you are on medications or have a chronic health condition. These factors can alter your fat-loss target heart rate.

Fat-burning heart rate chart

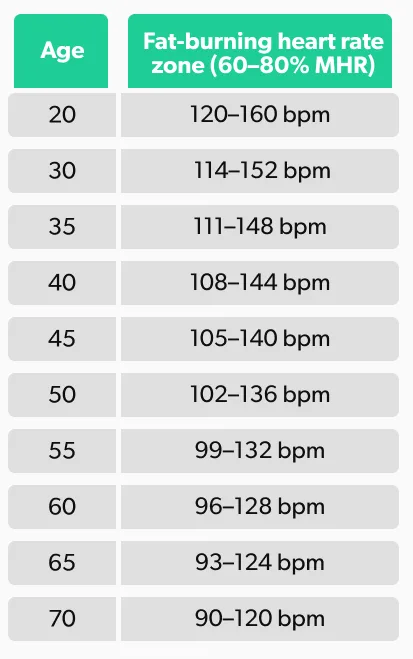

Your heart rate increases during exercise to keep up with your body's oxygen demands. Fat loss is triggered when your heart rate is in a steady state in a particular zone (meaning your heart rate remains in a certain zone for a certain amount of time).

Researchers have found that the best target heart rate for fat loss seems to be 60–80% of your maximum heart rate or MHR (Carey, 2009). To figure out your fat-burning heart rate, you first need to calculate your maximum heart rate—simply subtract your age from 220.

For example, if you are 40 years old, your max heart rate would be 180 bpm (220 - 40 = 180). This means 180 bpm is the maximum number of times your heart can safely beat per minute while exercising. However, you can’t sustain your maximum heart rate for the entirety of a workout. That’s where heart rate zones come into play.

Here is a handy chart that breaks down fat-burning heart rate zones by age. Note that these are averages, and your fat-burning heart rate zone may differ.

Other benefits of exercise

Of course, burning fat is not the only reason to get your heart pumping. Exercise has other cardiovascular benefits, and it can improve heart health by helping (Nystoriak, 2018):

Lower blood pressure

Increase insulin sensitivity (how well your body uses insulin)

Maintain a regular resting heart rate (so your heart doesn’t have to work as hard)

Reduce the risk of coronary artery disease

To achieve these benefits, you want to shoot for the lower end of your fat-burning heart rate zone for moderate-to-lower-intensity exercises and closer to the higher percentages for more intense exercises (CDC-b, 2022).

How to measure your heart rate

Technology has made monitoring your heart rate during exercise easier than ever. Wearables, fitness trackers, and mobile apps use sensors and algorithms to collect detailed data on your heart rate zones.

Some of the best available tools to measure heart rate include (Pasadyn, 2019):

Activity trackers

Chest straps

Smartwatches

Taking it manually during exercise (count pulse for 15 seconds and multiply by 4)

Studies have shown that chest straps and wearable fitness trackers are relatively accurate at continuously monitoring heart rate. Ultimately, the device you choose for monitoring your heart rate comes down to personal preference, budget, and convenience (Chow, 2020).

What workouts are good for burning fat?

The number of calories and maximum fat you burn during your workout depends on exercise intensity. Studies show moderate-intensity exercises are ideal for burning fat, while high-intensity workouts improve aerobic fitness and may burn more calories overall (Carey, 2009).

Moderate intensity exercises that put you in the fat-burning zone include (CDC-a, 2022):

Brisk walking (3 miles per hour)

Gardening

Water aerobics

Cycling on flat terrain

Tennis

Ballroom dancing

High-intensity workouts that put you in the aerobic zone include (CDC-a, 2022):

Cardio

Jogging

Hiking uphill

Cycling (10 miles per hour)

Heavy gardening

Dancing

Elliptical machine

High-intensity interval training (HIIT), which combines low-intensity exercises with intervals of high-intensity exercise (such as sprinting), may also be effective at reducing belly fat and promoting weight management (Boutcher, 2011).

Other ways to burn fat

Aside from exercise, there are other things you can do to burn fat and minimize weight gain, including:

Eating a well-balanced diet—High-protein foods and high-fiber fruits and vegetables may help you feel fuller longer, thereby reducing body fat (Simonson, 2020; Gardner, 2018).

Getting plenty of sleep—Not getting enough shuteye may make it harder to lose weight (Wang, 2018).

Consuming healthy fats—Olive oil, nuts, coconut oil, and avocados may be associated with long-term weight loss (Locke, 2018).

Understanding your fitness level and limitations is critical to developing a successful workout routine to keep you in the fat-burning zone. Switching it up between low and high-intensity workouts can keep you motivated, burn more calories, and help you achieve your healthy weight goals.

DISCLAIMER

If you have any medical questions or concerns, please talk to your healthcare provider. The articles on Health Guide are underpinned by peer-reviewed research and information drawn from medical societies and governmental agencies. However, they are not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

American Heart Association (AHA). (2015). All about heart rate (pulse) . Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/the-facts-about-high-blood-pressure/all-about-heart-rate-pulse

American Heart Association (AHA). (2021). Target heart rates chart . Retrieved from https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/fitness-basics/target-heart-rates?gclid=Cj0KCQjwkruVBhCHARIsACVIiOxHLUpQ5w1xq69627G8H6OZYKmWSrvrf-eGlP4YZ6jBqJOQvAGtoncaAuGeEALw_wcB

Boutcher, S. H. (2011). High-intensity intermittent exercise and fat loss. Journal of Obesity , 2011 , 868305. doi:10.1155/2011/868305. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2991639/

Carey, D. G. (2009). Quantifying differences in the "fat burning" zone and the aerobic zone: implications for training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23 (7), 2090–2095. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac5c5. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19855335/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC-a). (2022). Measuring physical activity intensity . Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/index.htmlCenters for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC-b). (2022). Target heart rate and estimated maximum heart rate. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/heartrate.htm

Chow, H. W. & Yang, C. C. (2020). Accuracy of optical heart rate sensing technology in wearable fitness trackers for young and older adults: validation and comparison study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8 (4), e14707. doi:10.2196/14707. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32343255/

Gardner, C. D., Trepanowski, J. F., Del Gobbo, et al. (2018). Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: the dietfits randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 319 (7), 667–679. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0245. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29466592/

Kapoor, M. P., Sugita, M., Fukuzawa, Y., et al. (2017). Physiological effects of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on energy expenditure for prospective fat oxidation in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 43 , 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.10.013. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27883924/

Locke, A., Schneiderhan, J., & Zick, S. M. (2018). Diets for health: goals and guidelines. American Family Physician, 97 (11), 721–728. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30215930/

Nystoriak, M. A. & Bhatnagar, A. (2018). Cardiovascular effects and benefits of exercise. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 5 , 135. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2018.00135. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6172294/

Ó Hartaigh, B., Gill, T. M., Shah, I., et al. (2014). Association between resting heart rate across the life course and all-cause mortality: longitudinal findings from the Medical Research Council (MRC) National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68 (9), 883–889. doi:10.1136/jech-2014-203940. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4292875/

Pasadyn, S. R., Soudan, M., Gillinov, M., et al. (2019). Accuracy of commercially available heart rate monitors in athletes: a prospective study. Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy, 9 (4), 379–385. doi:10.21037/cdt.2019.06.05. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6732081/

Simonson, M., Boirie, Y., & Guillet, C. (2020). Protein, amino acids and obesity treatment. Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders, 21 (3), 341–353. doi:10.1007/s11154-020-09574-5. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7455583/

Wang, X., Sparks, J. R., Bowyer, K. P., et al. (2018). Influence of sleep restriction on weight loss outcomes associated with caloric restriction. Sleep, 41 (5). doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy027. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29438540/

Zamora, F. Z., Martínez Galiano, J. M., Gaforio Martínez, J. J., et al. (2018). Olive oil and body weight. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Revista Española de Salud Publica, 92 , e201811083. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30461730/